What Charlie Chaplin's Last Movies Were Like Before He Died

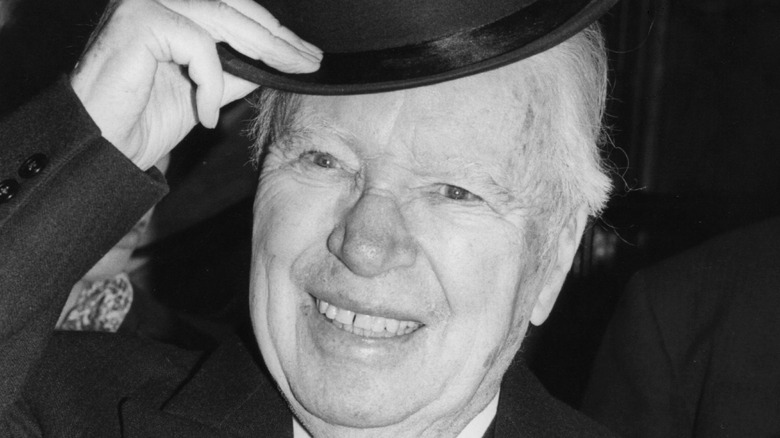

Storytelling may have been simpler in the days before CGI, but it was no less moving — and that's one of the reasons some characters have stood the test of time. Decades after Charlie Chaplin first strolled onto screens dressed as the Tramp, he's still one of the most instantly recognizable characters — and actors — in movie history, even though he was mostly featured in a few silent films.

When Chaplin died, he was a respectable 88 years old. Doctors reported (via Variety) that he passed peacefully in his sleep, and he was surrounded by his children and grandchildren, his wife at his side. The holidays would never be the same: It was December 25, 1977. In announcing his death, his widow remarked, "All the presents were under the tree. Charlie gave so much happiness and, although he had been ill for a long time, it is so sad that he should have passed away on Christmas Day."

In the decades leading up to his death, Chaplin was only involved in a few films — and they're each a "last" in their own right, and in a way that only makes sense in the context of Chaplin's final years. There's his last American film, which is widely considered to be his fond farewell. There's his last leading role, and then, there's the last film that he worked on. To leave any out is to overlook an important part of cinematic history, so here are what Charlie Chaplin's last movies were like before he died.

His final films were influenced by 1940s-era backlash

Talking about Charlie Chaplin's last films needs a bit of backstory, because building events in his real life greatly influenced the work he did at the end of his life.

By the time the seeds for his final American movie, "Limelight," were planted, it was on the heels of considerable controversy. Chaplin had ridiculed Hitler in "The Great Dictator," while in real life, he suffered through a very public paternity lawsuit. The New York Times says that when he followed that all up with a movie about a man who married women then killed them for their money, it really didn't do him any favors in the court of public opinion. His "Monsieur Verdoux" was widely condemned, and when there were calls to have him investigated by the House Un-American Activities Committee, he was.

Chaplin was devastated, says Slate, and decried one press conference around the release of "Monsieur Verdoux" as "a political brawl." He continued, saying, "I have nothing further to say." In that context, then, it makes sense that Chaplin would next write "Limelight," which returns to a place of nostalgia... kind of. Time has a relentless way of marching onward, after all, and it's fitting that Chaplin's last American movie saw him returning to the music halls of his youth, portraying an older performer who has found his once-adoring public no longer sees him as the beloved star he once was ... much like Chaplin saw himself.

It was first written as a novel — that was never completely published

It's difficult to imagine how Charlie Chaplin must have dealt with his very public fall from grace, but the interesting thing is that "Limelight" remains as a bit of insight into that world — and into the way it drove the creative processes behind his final films. They are deeply personal works: "Limelight" is heavily nostalgic, with two main characters — Chaplin's alcoholic, despairing Calvero and Claire Bloom's beautiful dancer — that echo Chaplin's own parents. Given that, it's perhaps not surprising to learn that the story that made it to the screen was only a small fraction of what Chaplin had written.

Chaplin had actually spent several years writing "Limelight" as a novel, but first, a bit of perspective: While word count depends on genre, a typical novel is roughly 100,000 words long — give or take. That's how much Chaplin wrote for "Limelight," including in-depth life histories for his main characters.

The book — which was called "Footlights" — was never meant for anyone save Chaplin. It wasn't until 2014 that 34,000 words of it were published, and according to The Guardian, it's heartbreaking stuff that echoes what Chaplin himself was going through. At one point, he wrote: "That's what I hate about getting old — the contempt and indifference they show you. They think I'm useless ... That's why it would be wonderful to make a comeback! ... As much as I hate those lousy — I love to hear them laugh!"

Limelight was released and — in many places — immediately banned

According to The Chaplin Office, "Limelight" was filmed in record time: just 55 days. Later, Chaplin's friend Norman Lloyd recalled that filming the movie — so overflowing with nostalgia — had revitalized him: "He was like the young Charlie. I would sit in his old-time dressing room being made up with him, and he was full of fire." While filming might have been good times, things quickly turned sour when it was released.

The public hadn't forgiven or forgotten the accusations that Chaplin was a communist, and many places banned or boycotted the film. According to the Los Angeles Times, it didn't even premiere in the city until two decades later (and only five years before his death). The Charlie Chaplin Archive has preserved documents calling for the movie to be pulled from public viewing — and many places made it perfectly clear what they thought of Chaplin.

The Philadelphia County Council wrote to Chaplin's distributor, United Artists, "Charles Chaplin by his repeated un-American behavior through the years has spurned the good will of the American people who must answer him in kind." Other letters — from organizations like The American Legion and attorneys representing movie theaters — pushed back against showing the movie, stating they didn't want to be associated with the communist controversy surrounding Chaplin.

The doors to the U.S. shut behind him

Charlie Chaplin was first signed to an American movie company in 1913. That predated even the character of the Tramp, so when he left on a promotional tour for "Limelight" in 1952, he had no reason to think that he wouldn't be allowed to return to the country he had called home for so many decades.

According to The Guardian, he had hardly left the country — on what he thought was going to be a six-month trip at the longest — when the U.S. government opened formal proceedings to decide whether or not he was going to be allowed back.

At the same time that London film critics wondered about his status, Chaplin himself seemed to have no doubts: He wasn't a communist, he had done nothing wrong, and he was even making plans for his next movie. Those plans would change when Chaplin suddenly found himself no longer able to set foot into the country he'd called home: He ended up settling in Switzerland, and would only visit the U.S. once more in his lifetime. (That was in 1972 — two decades later — for an awards ceremony.) His last films would be made outside of the U.S., even though his last starring role was in a movie set in New York.

The New York movie that was filmed in London

While most of Charlie Chaplin's best films had the backing of studios, that wasn't the case with "A King in New York." According to The Chaplin Office, the nearly 70-year-old Chaplin starred in just one movie after his exile from the U.S. — and they suggest that it was a frightening departure from the environment that he had been accustomed to.

Gone were the days of limitless financial backing, endless time, and a familiar staff. Instead, Chaplin needed to rent the studio, and every day cost money. This led to shooting the entire movie in just about three months, cutting corners where he could, and taking the scenes as they played out in front of him, instead of spending take after take getting it precisely perfect. Everything suffered, from the lighting to how convincing the sets were (not very), and it's only really in comparing this film to previous ones that it becomes apparent just how much had changed.

The content of the film was a drastic change from Chaplin's previous work as well: Although it was set in New York, it starred Chaplin as a displaced ruler who meets a boy — played by his son, Michael — who's caught in the middle of a conflict with the House Committee on Un-American Activities... which was a very obvious throwback to what Chaplin had been dealing with in recent years.

Chaplin's last starring role didn't get a U.S. reception

If the plot of "A King in New York" sounds like something that wouldn't get screened in the U.S., that's because it didn't — not for a whopping 16 years (via The Chaplin Office). And here's the weird thing: According to Roger Ebert, after the film was released in Europe, stories started circulating through the U.S. They claimed that Chaplin had turned on his adopted homeland entirely, and that he had made a movie that was a vicious condemnation of American life and values. Had the U.S. been right to close the doors and refuse to let him back in? Clearly!

Ebert went on to say that after the U.S. release of the movie in 1972, it became obvious that absolutely none of that was true. He wrote that the fearmongering Chaplin and his work were subjected to could have only been a consequence of "the hysterical frenzies of the Joe McCarthy era," and for all of the controversy surrounding it, he found that by the time it was released in the U.S. — and there had only been limited showings — that it had been generally well-received. That, he suggested, had something to do with the hopeful spirit captured in the last line: "This madness won't go on forever. There's no reason for despair."

He was already suffering from illnesses and ailments that would lead to his death

The very last film in Charlie Chaplin's filmography is "A Countess from Hong Kong." Released in 1967, it's the story of a Russian countess who boards a ship heading from Hong Kong to America — and with no passport and no status, hijinks ensue. It's a little different from Charlie Chaplin's other films, in that he only has a small part in it: Most of his work is done behind the camera.

While tracking down things like precise medical records is understandably tricky, it seems as though Chaplin was already suffering from ill health at the time of filming. According to History Revealed, Chaplin had started suffering from strokes as early as sometime in the 1960s. In The New York Times announcement of his death in 1977, they noted that his passing came after years of ill health.

Specifics are hard to come by, but it's safe to say that if Chaplin's medical issues started in the 1960s, he might have been dealing with problems even bigger than Marlon Brando. His obituary suggests that he knew his best days — and best films — were in the past, as he considered his early days of filmmaking to be the best. Variety noted, too, that he had been struggling with health issues for years, and gradually became reliant on both a wheelchair and oxygen.

Tippi Hedren wrote about his unique directing style

Charlie Chaplin's last film had an impressive cast that included Tippi Hedren, Sophia Loren, and Marlon Brando. It was Hedren who wrote a piece for The Guardian about the film and her work on it, which nearly didn't happen. At the time Chaplin called, she was just two weeks out of her exclusive contract with Alfred Hitchcock, during which time he'd refused to let her work with anyone else. From Hitchcock to Chaplin: It was a massive change.

"Chaplin's method was to act out all our different roles, which was brilliant to watch," she wrote. "Instead of directing, he'd get out there on set and say, 'OK, do this,' and show us how. He'd become Sophia Loren. He'd become me and Marlon. It was really unusual and I'd never seen it happen before."

The set wasn't without conflict, Hedren recalled, and not only had she been grateful to do it — and to work with Chaplin — but she'd become real-life friends with Loren.

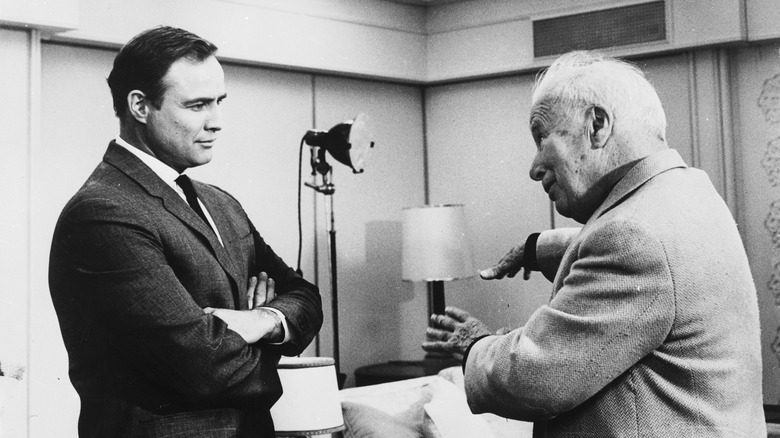

Marlon Brando vs. Charlie Chaplin

Work on "A Countess From Hong Kong" didn't always go swimmingly or smoothly, and a huge conflict unfolded on set. While Tippi Hedren wrote (via The Guardian) that she was fascinated to see Chaplin direct by becoming their characters, Marlon Brando was less than thrilled — and in fact, he'd threatened to walk.

Brando's biography, Songs My Mother Taught Me, came out in 1994, and he didn't pull any punches when he wrote about filming under Chaplin's unconventional guidance. He wrote, "Comic genius or not, when I went to London to work with him late in life, Chaplin was a fearsomely cruel man. ... [He] was probably the most sadistic man I'd ever met. He was an egotistical tyrant and a penny-pincher."

It probably didn't help, says Far Out Magazine, that Brando was far from Chaplin's first choice for leading man. Still, Hedren recalled that Brando was outraged that anyone on set would dare to play his character in front of him, and Brando himself said that things really came to a head when he was 15 minutes late arriving on set. While Brando admitted that it hadn't been very professional of him, he thought that Chaplin's public berating was even less professional. Brando, fortunately, got the apology he demanded.

Brando was outraged on behalf of Chaplin's son

Charlie Chaplin had multiple children, including his daughter, Geraldine (pictured, rehearsing for "A Countess from Hong Kong"), and his son, Sydney. According to Sydney's obituary in the Los Angeles Times, his first acting role was as a composer in "Limelight." He was also in "A Countess from Hong Kong," where he played the right-hand man of Marlon Brando's character. Sydney was quoted in his obit as saying that his father was "a strange man [who] had great difficulty expressing his feelings," and according to what Brando wrote in his memoir, "Songs My Mother Taught Me," that was putting this politely.

Brando was horrified at how Chaplin treated his son on set, saying every comment directed toward him was sarcastic, humiliating, and belittling. He wrote, "It was painful to watch, especially after Sydney told me that Chaplin treated all his children this way."

Brando tried again and again to convince Sydney that he needed to stand up to his father, but Sydney, he said, always had an excuse ready as to why it wasn't a good time. Of utmost concern? The elder Chaplin's continually worsening health. Brando wrote, "I said, 'None of that's an excuse for being so sadistic, especially to your own son.' But I could never persuade Sydney to stand up to his father, and he continued to take the abuse." Sydney died in 2009; his older brother, Charlie, died the year after "A Countess from Hong Kong" was released.

His musical talents crossed between films

Charlie Chaplin's final films had a surprising connection: Award-winning scores that Chaplin wrote himself. But the story of those scores is anything but straightforward, starting with the way that he wrote them. When he sat down with Life magazine around the release of "A Countess from Hong Kong," (via Scraps from the Loft), he described his methods. Explaining that he couldn't write music, he would recite directions to someone who could: "I will say, I want the flutes and nothing but the woodwinds here, and doing something, with a little brass here, French horns coming in here, and the climax there — something like that."

That sounds like it couldn't possibly work, but it did — and one of the songs Chaplin wrote for his final movie became a massive hit. That was "This is My Song," which was performed by Petula Clark and went to Number 3 on the Billboard charts.

Chaplin also won an Academy Award for Best Original Score, but here's where things get weird — and where a Chaplin history lesson comes in handy. Chaplin's award came in 1972, but it wasn't for "A Countess from Hong Kong." It was actually for "Limelight," and according to Turner Classic Movies, 1972 was the first time the movie was screened in Los Angeles, was the first time that it was eligible for an award, and won — two decades after it had been completed as Chaplin's last American movie.

Charlie Chaplin's directorial swan song was not well-received

Sadly, "A Countess from Hong Kong" has traditionally not been counted among Charlie Chaplin's best. With a 43% rating on Rotten Tomatoes, it's described almost universally in unflattering terms. The New York Times was even less kind when the movie premiered, writing, "And if an old fan of Mr. Chaplin's movies could have his charitable way, he would draw the curtain fast on this embarrassment and pretend it never occurred."

Simply put: It was a flop, not only as a career wrap-up, but it was a flop at the box office, too, in spite of the big names of the cast.

In hindsight, at least, not everyone hated it: The Harvard Crimson noted that Chaplin had hailed "A Countess from Hong Kong" as one of his favorites among all the movies he'd done, and they suggested he was correct. And when the San Francisco Chronicle looked back at it in 2017, they noted that while it had been widely panned for awkward acting and even more awkward dialogue, but looking beneath all that revealed something definitely worth watching. They saw a sentimental Chaplin depicting a stateless wanderer, looking to belong. They wrote: "'Countess' is like the artist's deeply personal confessions in a diary, revealing Chaplin's death wish: waltzing the night away."