Drivers Killed During The Indy 500

Few things are more American than the Indy 500: It's even held on Memorial Day weekend. Throw in some burgers, pulled pork, and BBQ sandwiches, a few cases of Bud Light, and end the day with some fireworks, and it's safe to say that it's almost aggressively American. And that? That just makes the death-defying spectacle all that more impressive.

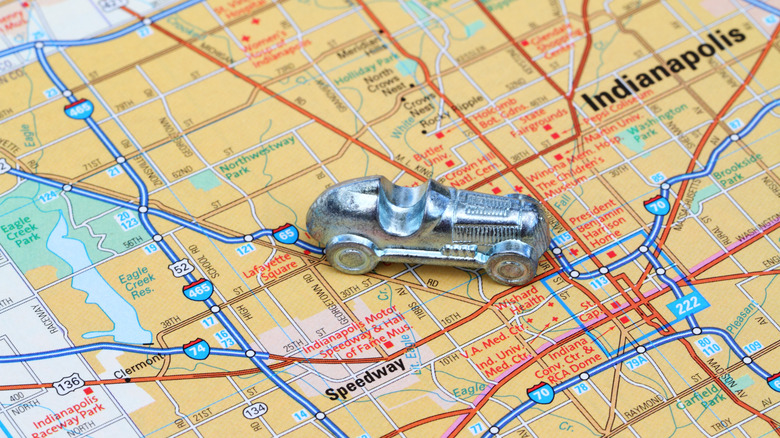

The Indianapolis Motor Speedway wasn't originally built as a racetrack but was instead used to test cars. It was only a few years after the track's construction in 1909 that someone said, "Let's do it faster, bigger, better, and with more..." and the Indy 500 was born. It's not all fun and games, though, and part of the nail-biting excitement is knowing that tragedy could strike at any moment, turning the race from a celebration of automobile engineering and driver reflexes into gruesome final moments.

Interestingly, there's a bit of trivia here, too. The turns are built the same, but it's the first one that has a bit of a reputation. Drivers have said it's one of the most intimidating pieces of track in the sport, and have cited everything from strange shadows to differences that are all but imperceptible ... until you're rocketing along at 230 mph. Driver Scott Sharp described it to The Wall Street Journal: "It looks narrower. You feel the car load up. It feels like you're on a knife's edge." Terrifying? It is: And some drivers have paid for the sport with their lives.

Arthur Thurman

First, for the sake of completeness, let's mention the person who has the dubious honor of being the first killed at the Indy 500. The accident happened the very first time the race was held, way back in 1911. According to the Indy Motor Speedway, driver Arthur Greiner and mechanic Sam Dickson — because these were the days when mechanics went along for the ride — were 12 laps in when one of the tires came off the car. Both men were thrown clear, and Dickson died on impact with a nearby fence. Greiner survived.

The first driver to die in the Indy 500 was Arthur Thurman, and it's safe to say that his story isn't one that would be repeated in the 21st century. Thurman wasn't just a rookie driver, he was a complete novice: The 1919 Indy 500 was his first race. That's not to say he didn't know what he was doing, though, and he was driving a car that he'd actually built himself. Thurman — who was actually a practicing lawyer in Washington, D.C. — showed up to be a serious contender ... until the 45th lap. That's when a wheel came off his car, and when he lost control, he was thrown from the vehicle. He survived the impact but died moments later, his wife watching from the stands with around 125,000 other people. His mechanic suffered severe injuries that included a fractured skull and was rushed to the hospital.

Louis LeCocq

The 1919 Indy 500 marked the race's return in a post-World War I world, and there was no photo finish: The winner crossed the line a full four minutes ahead of the second-place driver. Still, the excitement was marred not only by the death of driver Arthur Thurman but the subsequent deaths of another driver and his mechanic.

And it was graphically awful. According to Motorsport Memorial, Louis LeCocq's Dusenberg literally exploded when he and mechanic Robert Bandini were on the 97th lap of the race. The force of the explosion flipped the car, and the two men — who were strapped into their seats — were trapped beneath the burning car.

When The New York Times reported on the race, it ended up being a fascinating look into the sensibilities of a war-weary generation. They wrote: "The accident to Thurman did not cause them to diminish their speed and the crowd, at first horror-stricken, settled down to witness the finish of the long grind." That, they say, is when LeCocq's car exploded — likely due to the stress of taking a turn too fast. The report continued: "The flaming gasoline, which was sent in all directions when the tank of Lecocq's (sic) car exploded, was picked up by some of the racing cars and carried to several parts of the speedway." The race, meanwhile, continued, leaving rescue crews to fight the flames ... and dodge the racing cars.

Bill Spence

The Associated Press's report on the 1929 Indy 500 looks a little jaded to modern eyes, with headlines proclaiming, "BILL SPENCE KILLED. While No Records Were Broken It Was Full of Thrills." Yikes?

Spence was just 22 years old when he died on the second turn of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. The accident happened when his car swerved, the front tire clipped the wall, and flipped the car: Spence fell part of the way out, and was pronounced dead from a skull fracture. Eerily, the crash didn't end like it might seem like it would have ended. His car righted itself and started going backward. Spence was, at that point, still alive. He died before arriving at the hospital, and there's another eerie footnote to this, too.

"Speedway" is a silent film from 1929, and it's the standard sort of story about an up-and-coming race car driver. Some of the footage was shot at the Indy 500 that year, and Spence's fatal accident was not only caught on film but was included in the final cut of the movie.

Mark Billman

There are some years that are worse than others, and that's pretty much true of life across the board. As far as the Indy 500 is concerned, 1933 was a very, very bad year that started with two deaths during the qualification races. Bill Denver and his mechanic Bob Hurst died during one of those races, and by the time the year's event was over, a total of five people would be dead.

Mark Billman's death was the sort of thing most people would hesitate to wish on their worst enemy. The Indy Motor Speedway's memorial section describes Billman's Indy 500 run as "masterful," and for a while, it was. He was 80 laps into the race when he lost control, hit one wall, then crossed the track to hit the other wall with so much force that his car took out part of the concrete barrier. Billman was thrown from the car, which then bounced and came down to land on him. (His mechanic was thrown clear and survived.)

Depending on the sources, his left arm was either torn off in the crash or amputated as rescue workers labored to free him from where he was trapped between his car and the concrete barrier. Suffering from massive internal injuries and multiple broken bones, he survived for less than an hour after the horrific crash.

Lester Spangler

Lester Spangler's Indy 500 experience went from near the head of the pack to over in a heartbeat, with one ill-fated attempt at overtaking another driver. As memorialized with the Indy Motor Speedway, Spangler attempted to pass a competitor at the same time that competitor would later say he had made his own course correction to avoid a car that had started to skid in front of him. Spangler was sandwiched between a car and a wall, and after his own car was launched into the air, it came down on the outside wall.

Both he and his mechanic, G.L. Jordan, were thrown clear ... and onto the track. Both also suffered major injuries — including skull fractures — and died in the following hours.

Interestingly, there's a bit of trivia attached to this deadly year as well. The number of cars that participate in the Indy 500 is well-known to be the iconic 33 today, but that wasn't the case back in the 1930s. In fact, spectators at the 1933 race saw the biggest field of cars to date: 42. Even though safety regulations suggested leaving 400 feet of track for each car was the way to go, the thinking was that allowing more cars to compete during the Depression-era races would be a much-needed boost to the economy and to morale. Did the crowded track lead to the race's deadliest year? It's hard to tell, but the 33-car cap (with only a few exceptions) was adopted the following year.

Clay Weatherly

The irony surrounding the 1935 death of Clay Weatherly is far from lost. For starters, that was the year that new safety features — like traffic lights and helmet requirements — were added to the Indy Motor Speedway. Still, what followed was a race that led to the deaths of four people over the course of qualifiers and the actual race itself.

Things first went badly during a practice run for driver Johnny Hannon and mechanic Oscar Reeves. The practice run was critical for him, and several experienced drivers stressed the importance of adjusting to the difference between racing on dirt and on brick. On Hannon's first lap, he lost control, smashed through a concrete wall, and he was thrown from the vehicle. Suffering massive injuries including a crushed skull and chest, he died almost immediately. His mechanic was hospitalized for severe injuries.

Now, on to the arrival of a driver named Clay Weatherly. It was going to be his first time competing, but he had a massive problem: He didn't have a car. Weatherly approached the owner of the car that Hannon had died in, and it was agreed that the car would be rebuilt — in a matter of days — and Weatherly would drive it in the official race. Just 10 laps in, Weatherly lost control, plowed through one wall, hit another, and died of injuries that included a crushed skull and chest — just like the previous driver. Like the previous mechanic, his was also hospitalized for spinal injuries but survived.

Floyd Roberts

Floyd Roberts has a rather dubious honor: He not only won an Indy 500 race, but he also died in one. In 1938, Roberts took home the victory — and sadly, his wife wasn't even there to see it. According to a fascinating tidbit in "The Official History of the Indianapolis 500" (via IndyStar), she was back home in California and had gone to work that day as if it was any other, regular old day. Except, of course, for the race... and the holiday pay she got by going to work on Memorial Day weekend.

The Indy Motor Speedway recalls another eerie factoid: Roberts first hit the Indy track in 1935, and when he did, he was driving the same car that Lester Spangler had been driving when he and his mechanic were killed in 1933. The race he'd won, too, was darkened by tragedy: 1938's race included a freak accident where the flying tire from a crash hit and killed a spectator.

Roberts was 106 laps into his 1939 attempt at becoming a repeat Indy 500 winner when tragedy struck. When driver Robert Swanson lost control of his car, he collided with Roberts. Swanson was thrown clear, causing another car to swerve and flip. Roberts ended up breaking his neck in the collision and passed away at the hospital shortly after.

Shorty Cantlon

All deaths on the track of the Indy 500 are tragic, terrible, and heartbreaking, but the 1947 fatal accident that claimed the life of driver Shortly Cantlon was the sort of thing that makes even the most cynical person believe in some otherworldly power that makes things happen in our everyday lives.

As the Indy Motor Speedway notes, Cantlon was no stranger to speed: He set a world speed record in California, hitting a then-unheard-of 144.89 mph. Still, technology wasn't quite what it is in the 21st century: When Cantlon started his Indy 500 race, his car — the Automobile Shippers Special — actually stalled a few times before he got going. That meant a wildly challenging course ahead, but in a testament to his driving skills, he was actually coming up on the leader by the 41st lap. That, unfortunately, is when tragedy struck.

Driver Bill Holland's car suddenly spun wildly, and Cantlon was faced with a decision: Hit Holland, or hit the wall. Sources vary on what happened next: He either died on impact with the wall, or shortly after he was pulled from his wrecked car. Either way, his car wasn't removed from the course, and sat there — a horrifying reality check for the other drivers — for the remainder of the race. As for Holland, he placed second after waving his teammate ahead of him, thinking he was a lap ahead.

Carl Scarborough

In 1953, Indy 500 drivers would have something unforeseen to contend with: heat. Normally pleasant springtime temperatures skyrocketed, and by the time the race started, temps on the track had risen to a blistering 130 degrees Fahrenheit. It was so hot that the Indy Motor Speedway says drivers were beginning to suffer blisters even through their shoes, and before the race even started, some of Purdue's marching band had fainted from the heat. When the race began, tires began to burn on the cars.

Drivers were unanimously exhausted, and that makes for a dangerous course. After a near-miss, Carl Scarborough pulled off during his 69th lap. Refueling his car went about as bad as it could, and the gas set everything on fire as it hit the hot car. Motorsport Memorial says that Scarborough was still inside when fire crews put out the blaze. Heat exhaustion and carbon monoxide from the fire extinguishers had already overcome him by the time crews pulled Scarborough from the car, and when the ambulance reached him about 15 minutes later, he had an internal temperature of 104 degrees.

Attempts to revive him failed, and although he was taken to the hospital, he died about an hour and a half after he was pulled from his car.

Bill Vukovich

Bill Vukovich's story is pretty incredible: Born to a poor family of Yugoslavian immigrants, he grew up on a farm during the Great Depression, worked as a mechanic during World War II, and became determined to make racing the way he paid the bills (via ESPN).

By the time Sports Illustrated sat down with him before the 1955 Indy 500, he had already won twice — including the notorious, 130-degree race in 1953 that claimed the life of Carl Scarborough. Vukovich finished — alone, with no relief driver. He won again in 1954, and in 1955, he died. Reporter John Bentley would write about how drivers had "boosted the average speed ... beyond all reason. In 1946 it was 114.8 mph; last year nearly 131. This year," he continued, "it killed Bill Vukovich." Bentley was there and described the crash as starting with Roger Ward flipping his car, then causing a chain reaction of other drivers swerving, colliding, and flipping, all at high speed. Then, there came Vukovich: He hit another car, went over a guard rail, flipped several times, hit three vehicles parked alongside the track, and pinned him beneath what was left of his car ... which then burst into flames.

Vukovich was 35 years old at the time of his death, and his wife was in the stands, watching as another driver, Ed Elisian, stopped to try to help. Vukovich would be immortalized for his description of what it takes to win: "Keep your foot on the throttle and turn left."

Pat O'Connor

The term "catastrophic" can often be misused when it comes to sporting events: A bad call, a dropped ball, a flubbed play. But the 1958 Indy 500 really was catastrophic, and it kicked off with a risk taken by the same Ed Elisian who had stopped to help his friend Bill Vukovich after his deadly crash just a few years prior. It was on the very first lap that Elisian and another driver, Dick Rathmann, played a deadly game of chicken, collided, and started what would be a 15-car wreck and — according to the Indy Motor Speedway — the worst the race has ever seen.

Driver Pat O'Connor had started just behind Elisian and Rathmann, and when his car was flipped, he was killed instantly. Then, it burst into flames. Can it get more tragic? Yes.

O'Connor left behind a wife and an 18-month-old son, and in 2018, IndyStar spoke with one of the other drivers who had been on the track that day. It was A.J. Foyt's rookie year as a professional driver, and O'Connor had been his mentor. "When I turned around to see the car burning and his arm hanging out, I figured maybe I better go back to Texas," Foyt said. "It was [hard]. When someone helps you, and then you see them burn ... you know, it's hard. I don't care who you are. After that ... I had a lot of close friends, but I never really did get close with anybody after that." Elisian, meanwhile, was ostracized by other drivers and died in a crash the following year.

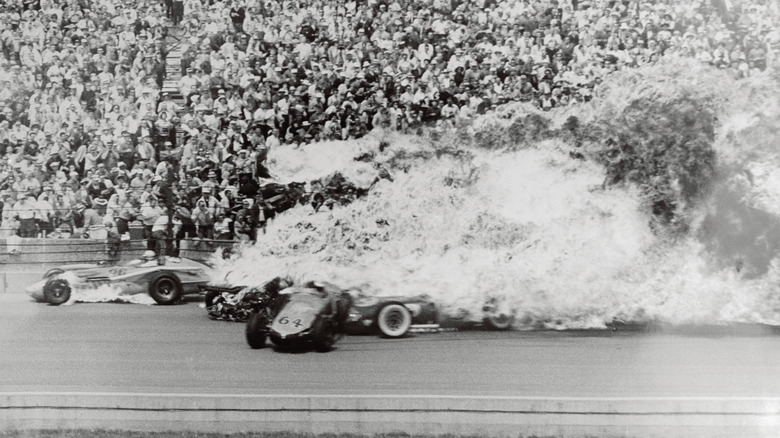

Dave MacDonald and Eddie Sachs

A terrible accident on the second lap of 1964's Indy 500 claimed the lives of two drivers, Dave MacDonald and Eddie Sachs. Both were big names: Sachs was celebrated as the so-called Clown Prince of Racing, while MacDonald had been behind the wheel when Carroll Shelby's Cobras first started racking up their wins. If he'd lived, he would have been headed to Le Mans — his place was reserved, and he was ready to go.

Whatever happened that day, happened fast — and it's not entirely agreed upon. The widely accepted story is that MacDonald brushed the wall, sparking a failure in his fuel system. Gasoline spewed, then caught on fire. MacDonald lost control, collided with Sachs, and the following fireball burned so big and so black that spectators couldn't even tell how many cars were involved. Driver Bobby Unser was quoted (via IndyStar) as saying, "The whole track was blocked with fire. I didn't know if it was one burning car or 10. It looked like 10."

Around 300,000 people were on hand to witness the crash, including the wives of both drivers killed. Several other drivers were badly burned, including rookie driver Ronnie Duman, and the incident opened a massive discussion on the safety of the cars designed to not only hit top speeds but carry a lot of very flammable fuel.

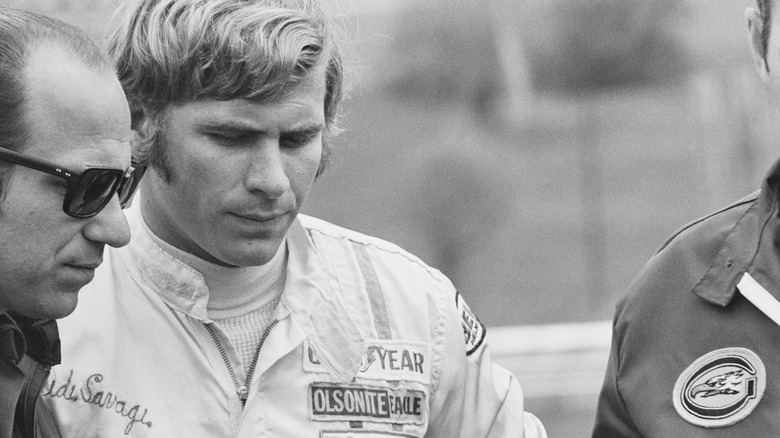

Swede Savage

When The New York Times reported on the 1973 death of Swede Savage, they quoted him as saying: "When I was 9 years old, my goal was to win the Indianapolis 500-mile race. It was the thing to do. All the kids I raced with dreamed about Indianapolis."

Savage technically didn't die on the racetrack, and exactly what happened is still debated. It's unclear whether poor track conditions caused him to lose control of his fully-fueled-up car on the 58th lap, or if the oil spilled from another car had something to do with it. Some witnesses said they saw a piece of his car break free right before the crash, but either way, Savage's car skidded across the track, hit the inside wall, and exploded.

Shockingly, Savage survived to be pulled out of the wreck, and in a terrible footnote, rescue crews rushing to the scene struck and killed a crewman when they attempted to take a shortcut. Savage was taken to a nearby hospital, and doctors made it known that they firmly believed he'd be back to racing in no time. On day 33 of his hospital stay, he passed away from complications of his injuries: those complications have alternately been described as a kidney infection or liver failure resulting from a bad blood transfusion (per Motorsport Memorial). Savage was survived by his wife and son: His daughter, Angela, was born three months after he died, and later told Watchonista, "I was born with a broken heart."