The Tragic Real-Life Story Of Gregory Peck

It's no secret that Hollywood is a hard place to not only break into, but stay relevant. There's a slew of actors who have been honest about the fact that they took some roles — sometimes, their biggest ones — only for the money, and there's nothing wrong with doing what you need to do to make ends meet. Gregory Peck, however, was apparently a different story.

In 2023, his family put some of his personal items up for auction — including his script for "To Kill a Mockingbird." In an official statement through Heritage Auctions, his son Anthony Peck said, "He was so true to himself. He didn't take a single job for the money. He did what he wanted to do and what interested him — and honestly, that was helping others. It wasn't an act. It wasn't something he did for publicity. That's who he was. ... Harper Lee once said the role of Atticus Finch gave Gregory Peck the chance to play himself. Because he was that man." (Appropriately, a portion of the proceeds from the auction were donated to Chef Jose Andres' World Central Kitchen.)

Peck himself spoke about the longevity and popularity of the film, suggesting (via Entertainment Weekly) that it wasn't just the civil rights issues that appealed to multiple generations, but the interaction between a father and his children. He suggested that the loving relationship between a parent and children who always had time and kindness for each other speaks to everyone. Perhaps surprisingly, though, his own childhood was less than stellar.

There were accusations that his father was abusive

Gregory Peck's parents first separated when he was just 2 years old (yes, that's him pictured), and his mother filed for divorce in 1921, when the divorce rate was only about eight couples per 1,000 people. Although she ultimately withdrew the divorce petition, she resubmitted and finalized proceedings just a few months later. In Gary Fishgall's biography — simply titled "Gregory Peck" — he notes that while it's uncertain just what happened behind closed doors, Bunny Peck made some serious allegations about her husband, also named Gregory but more commonly known as Doc.

Bunny filed for and received a restraining order based on allegations of abuse, both of her and her young son. She claimed that not only was Doc verbally abusive, but that he had also accused her of cheating, gotten into a physical fight with her sister's husband, threatened Gregory, and even prevented her from seeking medical attention when her appendix burst.

Gregory later denied it all, saying, "Nothing like that ever happened. ... If you knew my dad, it is impossible." Fishgall says that his research suggests there was something to the allegations, though, especially considering the rarity of divorce at the time and the fact that she was granted a restraining order from the courts. After staying briefly with his father in California, Gregory was sent to live with his mother in St. Louis. He made the trip alone via train, aged 6, and recalled, "I wasn't scared. It was a big adventure."

The fate of his childhood dog left a decades-long wound

The luckiest kids are those who grow up with a beloved dog or cat as a best friend, and that's just a fact of life. Gregory Peck's love of dogs lasted a lifetime, and when he was interviewed by Barbara Lovenheim at his home in the late 1980s, she recalled (via NY City Woman) the elegant presence of a very large dog. When Peck spoke about his childhood, he recalled a happy time living with his mother and stepfather in California. Best of all? "My father scraped up money for a bike, and I found a black and brown mixed breed dog and named him Bud," he said fondly.

It wasn't all good, though, and in Michael Freedland's biography "Gregory Peck," the actor said that of all of his many years, "1924 was a bad year for me. I discovered that there was no Santa Claus, no Easter Bunny, and Bud was kidnapped."

Peck was never 100% certain what happened to his beloved dog (pictured). His grandmother tried to tell him that Bud had run away, but Peck learned that, after neighbors complained about Bud's barking, his own father had been complicit in the dog's disappearance. It broke Peck's heart: He said that he always wondered if Bud was given to a loving family, or "shall we say, otherwise disposed of. For the next 40 years I always took a second look at every black and brown mongrel I saw."

Sounds of his dying grandmother haunted him for years

It's sort of an age-old threat: military school. For Gregory Peck, that's precisely where he was sent when he was just 10 years old. Memories of attending the school were interspersed with living at home with his father and his paternal grandmother, but not long after he started attending St John's Military Academy and spending down time getting to know his father, his grandmother was diagnosed with stomach cancer.

Michael Freedland's biography recounts the lasting impact the slow, painful death of his grandmother had on Peck. At the time, there was not only no hope for survival, but there was no way to alleviate that pain that came with a slow wasting-away. Peck's bedroom was close to hers, and at night, he would lie awake and listen to her sobs. When he would go to sit with her, to read to her, to visit with her, she would try to hide the pain... but couldn't.

In an interview with Irish America, Peck spoke about the death of his grandmother. "At night, I'd hear the most terrible groaning. In the morning, I would read the newspaper to her, so I remember exactly what she looked like, but as far as her character, I remember strength and an almost stoic way of dying, except for the groaning, which I can hear to this day."

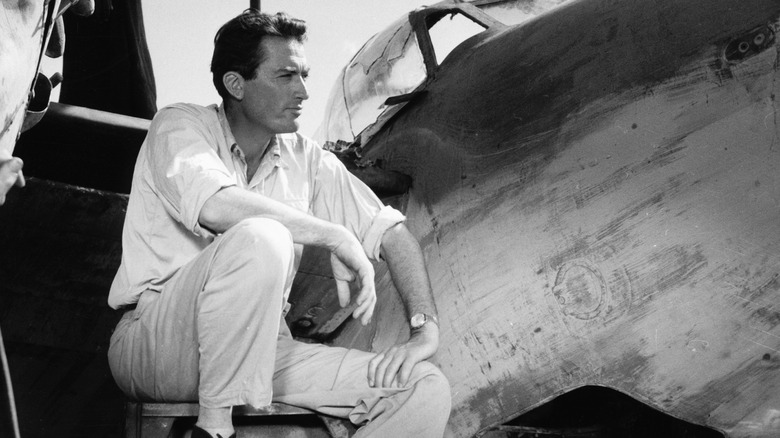

He was in constant pain because of a schooling exercise gone wrong

Anyone who lives with chronic pain knows that it can color your entire life and restrict activities. Some might suffer chronic pain because of an illness or an accident, but Gregory Peck was in pain for much of his life because someone did something very, very stupid, and critically injured him.

That someone was Martha Graham, the much-lauded pioneer of American dance. Early on in his career, Peck attended her stage movement classes, and during one stretching exercise, she felt he wasn't stretching forward far enough. To encourage him, she braced her knee against his back and pushed. In his biography of the actor, Michael Freedland writes that the snapping sound was so loud it was heard by everyone around him.

He later detailed the extent of his injuries in an interview with Irish America, saying that the following morning, he was unable to walk. "I had ruptured a disk in my lower back. The school sent me to an orthopedic specialist who put me in an old-fashioned canvas strap, which I wore for two or three years, and gradually, the condition began to remedy itself, though off and on it's bothered me all my life," he explained, and that's just part of the story. In addition to the ruptured disk, he also suffered a displaced vertebrae and pain that made him question whether or not it had ended his career.

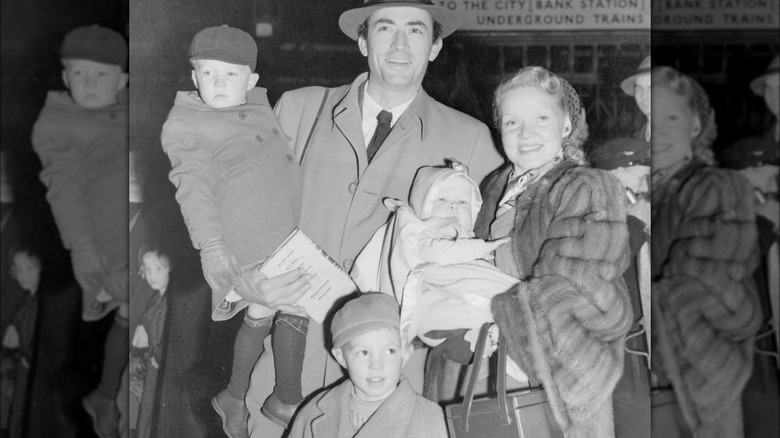

His marriage was something he merely tolerated

Gregory Peck's first marriage was to Greta Kukkonen, and according to Michael Freedland's biography, "Gregory Peck," Peck truly loved their three sons. But while he wanted to give them the childhood he hadn't really experienced, he and his wife were constantly at odds. She didn't approve of the never-ending need to move along with his career and the pressures that went along with that drive. He was only 34 years old when the stress — and the feeling of being trapped — got so bad that he suffered what he believed was a heart attack.

Pills and alcohol got him through the days, and after another fight, he headed out and spent a month of self-reflection in a Mojave Desert bungalow. It was there that he came to the conclusion that he would never be happy in the marriage, but he thought that he could cope with it for the sake of appearances and their children.

They remained married through the filming of "Roman Holiday" and even attempted to keep living together. In 1954, the Associated Press announced their official and final split, with her divorce proceedings citing "grievous mental suffering, great embarrassment and humiliation." Peck, meanwhile, told People in an interview that the hardest part about the split was wondering what it would do to his sons. "For three weeks, I just felt awful about the boys. I stayed in my hotel room like a bear in a hollow log."

His cousin died in a horrible way

When Gregory Peck sat down for an interview with Irish America, he shared that he'd often gone back to the country where his father had largely been raised to visit the family he still had there. "[My father] always had a bit of a brogue, and he loved to tell stories," he shared. "He used to talk about being a boy in Ireland, and say that there was no entertainment other than telling stories or singing a song..." And although it might be popular to talk about the luck of the Irish, they're a nation with a very dark, very difficult history — and it's one that touched Peck's family.

Peck shared that his cousin was Thomas Ashe, a teacher-turned-freedom-fighter who participated in the Easter Rising as a commander who led a series of raids against occupying British forces. Afterward, he fell in alongside Michael Collins, and it was Collins who wrote in a letter, "Tom Ashe has been arrested, so that fixes him."

He was chillingly correct. Held in the rather inappropriately named Mountjoy Prison, Ashe led other prisoners in a hunger strike. When he was pulled out of his cell and force-fed, the doctor performing the brutal procedure punctured Ashe's lung. He survived for two days before dying of what was officially described as "heart failure and congestion of the lungs," a ruling that was widely condemned across the country. Ashe's death led to a massive surge in the recruitment of those willing to fight for a free Ireland.

His son's suicide was devastating

Gregory Peck was living in France in 1975, and it was there that he learned his son, Jonathan, had died by suicide. According to Michael Freedland's biography, "Gregory Peck," Peck had always been close to all of his children. He had known Jonathan was dealing with a lot, including the end of a relationship, the stress that went along with working in the news industry, health-related problems that included vascular disease, and the suicide of a former girlfriend. Peck had even given his son money and instructions to find and speak with a therapist.

According to Michael Freedland's book "Gregory Peck," that time was one of Peck's greatest regrets. "My regret that I'll live with for the rest of my life was that I was in France instead of here. I felt certain that had I been in Los Angeles he would have called me, because he often dropped in and talked things over with me. If only he could have picked up the phone and said, 'Things are just bearing down so much on me tonight, that I can't stand it,' I would have said, 'Stay where you are, I'll be there.'"

Peck was married to his second wife, Veronique Passani, at the time, and she described the grief as insurmountable. It led Peck down the road of questioning: What kind of father was he, what had he done wrong, what could he have done better? There were, of course, no easy answers, and Passani suggested that the only way he got through it was with the strength of the family.

His obsession with the steeplechase came with a horrific ending

The Grand National horse race is still held annually, in spite of regular protests. Anglia Ruskin University lecturer in animal welfare Dr. Mark Kennedy has said that the risk of horses dying is high, and put it in these terms to the BBC: "If the risk to the car driver was the same as the Grand National — six deaths in 1,000 — then you would be lucky to still be alive after six months." Gregory Peck decided he was going to get into horses and steeplechase, and his horses were among the sport's casualties.

The first was named Owen's Sedge, and according to the Michael Freedland biography "Gregory Peck," the horse was widely publicized as belonging to the actor. After so-so showings, he was entered in a Grand National preliminary race, where he died on the course. Coming out of a jump, he landed with his legs stretched in front and behind him, breaking his pelvis and severing major arteries. He briefly regained his feet and staggered a few broken steps before finally collapsing.

Peck bought another horse: Different Class placed third in 1967, but the following year, he was involved in a massive accident involving 14 horses. He continued to race before eventually developing both heart and liver trouble that led to euthanasia.

Loneliness was a constant theme throughout his life

Does success fix all problems? It turns out that it doesn't, and in Gary Fishgall's biography "Gregory Peck," the actor spoke about how never having a stable family life that included his parents took a toll on him. "I never remember once sitting around a dinner table with my family and having an ordinary kind of family conversation," he said. With no one to really share his emotions and feelings with, he learned to hide them beneath an exterior that was what he believed people wanted to talk to. The result? "I was lonely, withdrawn, full of self-doubt," he revealed.

That inability to connect to people and tendency to internalize his feelings led to broken friendships even when he was an adult. While filming "Moby Dick," he initially became good friends with director John Huston. They invested in horses together and planned future projects, and then? Peck ghosted him. Huston wrote: "Had it been almost anyone else, I would have said, 'The hell with it,' but not with Greg. I valued our friendship too much." He tried to figure out what he'd done, but to no avail.

Peck, it seems, had discovered that he hadn't been the first choice for that famous "Moby Dick" role: Huston had wanted Orson Welles, but Peck was deemed to be the better option who would guarantee the movie would get funded. He never forgot what he perceived to be a slight — it was too close to the childhood betrayals he had experienced.

Gregory Peck's death marked the end of an era

When Gregory Peck died in 2003 at the age of 87, it was the end of an era. His spokesman reported the circumstances of his passing, which were recounted in his obituary in The Telegraph: "[His wife, Veronique] was with him, holding his hand, and he just went to sleep. He had been getting older and more fragile. He wasn't really ill. He just sort of ran his course and died of old age." With his death, though, came the end of Old Hollywood.

Frank Pierson, president of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, explained the loss, saying (via the Los Angeles Times), "He was the last of the true aristocrats of the old Hollywood." Other organizations lamented his death, too: Motion Picture Association of America president Jack Valenti called him "a towering figure in the history of the movie industry, [who] made a series of films which illuminated great truths of character," while the American Film Institute doubled down on their promise to preserve and promote his films.

Peck was lauded not only for his acting ability and his choice in movie roles, but also the fact that he was an outspoken humanitarian who campaigned for causes from peace in Vietnam to cancer research. He once said, "I'm not a do-gooder. It embarrassed me to be classified as a humanitarian. I simply take part in activities that I believe in."