The Dark Truth Of Roaring Twenties' Get-Rich Scams

Everyone loves a good get-rich-quick scheme. It's often seen as an inspirational story that making millions of dollars with little-to-no effort is possible. But unfortunately, there's very little legitimacy behind them. If anything, these schemes are often scams that end up leaving a trail of victims behind them as the money starts to pile up.

In some ways, the 1920s were a golden age for get-rich-quick schemes because there was little regulation on fraudulent behavior. The stock market is a good example of this, which saw little regulation until after its fateful crash in 1929. Many of the phony enterprises of the 1920s centered around fraudulent stocks and manipulating the market.

In the end, few get-rich-quick schemes have a happy ending for everyone involved. But that doesn't mean that they've gone out of fashion. In fact, some of the most well-known scams today, like the Ponzi scheme, originated in the 1920s. Ultimately, the age-old adage "if it seems like it's too good to be true, it probably is," continues to ring true.

The original Ponzi

One of the biggest get-rich-quick schemes of the 1920s became so notorious that the name of its creator has become synonymous with scamming. In 1919, Charles Ponzi came up with a scheme that involved buying international postal reply coupons from outside the United States, before redeeming them for dollars within the United States. This was made possible due to international treaties that fixed the exchange rate of the coupons, so if the actual value of the international currency dropped, a relatively large profit could be reaped on the original coupon purchase.

Ponzi claimed to be able to offer investors 50 cents on the dollar, compared to the four to six cents offered by banks with bonds and savings accounts. Ponzi even claimed that he dealt directly with foreign governments and had a network of agents across Europe who bought postal reply coupons. But all of Ponzi's pontificating was nothing more than a scam. Although he paid off some of his first investors, Ponzi kept his scam going as thousands more people invested their money into his postal reply coupon business.

By July 1920, Ponzi was making $250,000 per day. And it's estimated that over the course of eight months, he made about $15 million – worth over $228 million in 2023 — making him one of the richest men in the United States. But when Ponzi was finally audited, only $61 worth of postal reply coupons were discovered. Meanwhile, investors lost over $20 million and five banks collapsed as a result of Ponzi's scheme.

Scamming close friends and relatives

Charles Ponzi didn't actually perpetrate the first Ponzi scheme, despite his name being given to them. Instead, one of the first Ponzi schemes, also known as a pyramid scheme, was instigated by Leo Koretz.

Koretz initially sold fake mortgages, but before long he was also making money off of land in Panama, having been inspired after becoming a victim himself of a similar scam. In 1917, Koretz started selling stocks for a timber and oil land syndicate in Panama, known as the Bayano River Syndicate, but neither the timber nor the oil nor even the five million acres of land itself existed. In total, Koretz scammed people out of $2 million, equivalent to over $30 million today. And it wasn't just strangers that Koretz scammed. When the Chicago Tribune first reported on Koretz's scams, they wrote: "[Koretz] made a specialty for years of systematically robbing only his relatives and close friends."

Like Ponzi and his eponymous Ponzi scheme, Koretz managed to keep people fooled as long as there were new investors coming in with more money. But in 1923, after a group of investors went down to Panama themselves to see the Bayano River Syndicate for themselves, it was then that Koretz's con was finally revealed. And like a row of dominos, all of his scams came undone one by one. Koretz was eventually convicted, and he died by suicide after one month in prison.

If you or someone you know is struggling or in crisis, help is available. Call or text 988 or chat 988lifeline.org

The Davis Islands

During the 1920s, the state of Florida experienced what was known as the Florida land boom, during which land was bought and sold in Florida for huge profits. Of course, this attracted creative speculators, such as a certain David P. Davis, who went on to construct the Davis Islands.

In 1924, Davis purchased two marshy islands in Hillsborough Bay, Tampa, for a real estate venture, and he didn't even have to build any houses before he'd made a profit. It only took three hours for all 300 of the lots of the Davis Islands to be sold, despite the fact that every single one of them was still partially underwater. Not a bad deal for a cool $1.6 million, although Davis only took home around $84,000 of the sale. Some people were jumping on the sale simply to make a quick buck themselves: Two lots were sold to Penn Dawson of Dawson-Thornton Dry Goods, and he made a profit of $1,000 by selling them almost as quickly as he'd purchased them.

Sadly for Davis, although he started construction on the islands as promised, the people who'd purchased lots didn't all end up paying for them. Although some of the first payments came in, Davis found himself in debt and, by 1926, was forced to sell Davis Islands to Stone and Webster. And as the Florida land boom ended, Stone and Webster themselves struggled to finish construction.

C.C. Julian's oil wells

When Courtney Chauncey Julian arrived in Santa Fe Springs, California, in 1922, it seemed like there was no end in sight when it came to oil speculation. But even though Julian had neither an oil well nor anything to drill with, he knew that all he had to do was convince people that he did. By 1923, he'd created the Julian Petroleum Corporation in Los Angeles and he advertised repeatedly in the newspapers, claiming: "I'm trying to offer you the squarest and surest opportunity for big returns that it is humanly possible to make," per PBS.

And the advertisements quickly drew investors. In his first few months Julian sold up to $5 million in stocks for the Julian Petroleum Corporation. But by this point, Julian only had a handful of oil wells, and they could never deliver on the millions that people were investing. By 1925, it was becoming clear that Julian was scamming people and the LA Times stopped printing his advertisements. And in 1927, Julian was charged with numerous counts, including conspiracy to obtain money under false pretenses, forgery, and embezzlement.

But in the end, Julian completely avoided standing trial for his scam, choosing to flee to Shanghai, China instead. He spent the rest of his life in Shanghai, although he died under mysterious circumstances, so it's unclear if he was poisoned by someone he scammed or if he died by suicide.

If you or someone you know is struggling or in crisis, help is available. Call or text 988 or chat 988lifeline.org

The Radio stock pool

The idea of using the stock market as a way to get rich quickly is an idea as old as the stock market itself. And because much of the stock market operates on speculation, it's not difficult to trick people into thinking that a stock is worth more than it is. And that's exactly what a group of Wall Street workers did in 1928.

In "Wall Street," Charles R. Geisst writes that in March 1928, Wall Street floor traders Tom Bragg and Ben Smith teamed up with Michael Meehan, a friend of Radio Corporation of America (RCA) chairman David Sarnoff, to drive up the price of RCA stock, known as Radio. With a group of friends, stocks of RCA were sold back and forth to one another, slowly driving up the price. According to The Commercial Radio Operators' Magazine, over the course of seven days, 844,000 shares of radio stock were bought and sold amongst the Radio pool traders. All the unsuspecting public saw was the stock rising, so people outside of the pool also started buying stocks.

As the stock price rose, the Radio pool cashed out, making almost $5 million in profits, with some reports claiming as much as $10 million in profit. And despite the fact that this group of Wall Streeters was conning the public, nothing they were doing was technically illegal. It wouldn't be until the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 that market manipulation, especially through stock pools, was made illegal.

The Osage people

One of the most notorious get-rich-quick schemes of the 1920s was a conspiracy perpetrated against the Osage people in Osage County, Oklahoma. After oil was discovered under Osage County in the early 1900s, the royalty payments went to the Osage people, who owned shares of the land and mineral rights. But as the Osage people became incredibly wealthy from the royalty checks, the United States government decided that the Osage people needed to prove that they were competent, otherwise a white person would be appointed as a guardian to control the incoming wealth.

Not only did those guardians pilfer the fortunes of the Osage people, but many Osage people whose fortunes were under guardianship were targeted for murder. The scheme involved white people marrying into Osage families and murdering them, in order to subsequently inherit their land and oil rights. Known as the "Reign of Terror," over 60 Osage people in Osage County were murdered between 1920 and 1925. The Brown family was one of many that was targeted, and Mollie Kyle Burkhart was the only one to survive the serial killings against her family, her story dramatized in the 2023 Martin Scorsese film "Killers of the Flower Moon." By 1924, guardians alone had stolen $8 million belonging to the Osage people.

Although the Bureau of Investigation briefly investigated the murders, convictions were limited, and the Osage people continued to be murdered well into the late 1920s.

Charles A. Stoneham's fraudulent bucket shops

In the early 1910s, Charles A. Stoneham, owner of the New York Giants, ran what was known as a bucket shop in the New York Curb Exchange, an unregulated version of the New York Stock Exchange. Bucket shops operated by not actually buying the stocks that their customers ordered, in the hopes that the stock would drop and people would sell, allowing the bucket shop to keep the difference.

According to Robert F. Garratt's "Jazz Age Giant," Stoneham had no qualms with using his bucket shops to make fast cash, especially since his predilection for gambling made his bucket shops attractive as another place to potentially win big. By 1920, Stoneham was said to be worth $10 million, equivalent to more than $152 million in 2023. But Stoneham's millions often came at the expense of investors' money. When Stoneham closed down the bucket shop he operated with Arnold Rothstein in 1922, other investors lost $4 million as a result. Another firm that Stoneham was involved with cost investors $5 million when it reportedly went bankrupt.

In the fall of 1923, Stoneham was indicted on federal fraud charges. Although he was eventually acquitted of all charges, there were reports that the trial was corrupted and no other charges ever stuck. Ultimately, while Stoneham was never convicted on any fraud charges, investors whom he'd defrauded brought numerous civil suits against him for years.

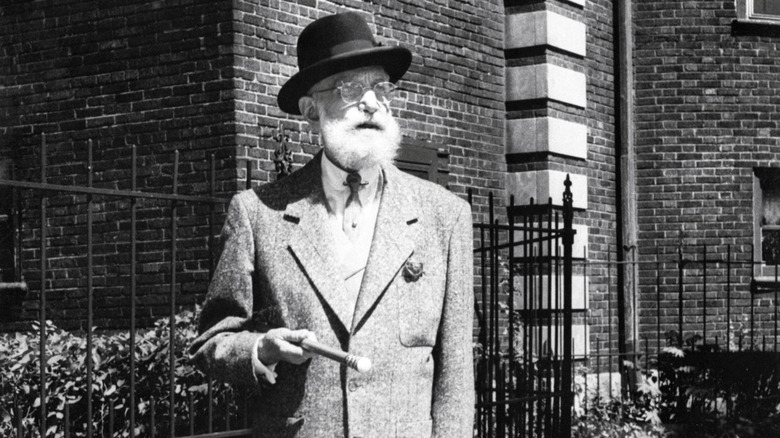

The king of con men

In the 1920s, no one was more notorious for his get-rich-quick schemes than Joseph "Yellow Kid" Weil, whose cons were so well-known that he was known as "The King of Con Men." And Weil's cons took many different shapes and targeted people of all income brackets. One of his schemes involved selling fake stock for an Indiana steel mill to a banker, out of which he profited more than $100,000, while another involved keeping a $3 check that he claimed he was collecting for a charity. Some of his smaller cons included selling talking dogs or staging fake fights.

One of Weil's biggest scams involved none other than Benito Mussolini, the prime minister and fascist dictator of Italy. When Weil was in Italy during the late 1920s, he fraudulently sold Mussolini mining lands in Colorado for $2 million. But Weil never saw himself as doing anything wrong, and later claimed: "Men like myself could not have existed without the victim's covetous, criminal greed," per "Don't Fall For It" by Ben Carlson.

Although Weil conned people for almost 40 years, and at the height of his wealth was worth over $8 million, he had less than $200 to his name when he died in 1976. But despite all of his fraudulent behavior, Weil spent less than 10 years of his life in prison, and died at the age of 100.

Victor Lustig and the Eiffel Tower

Victor Lustig's scam is considered to be one of the most notorious in history, for not only did he manage to sell the Eiffel Tower despite not owning it, but he managed to pull off that exact same con a second time.

In May 1925, after reading an article in a Paris newspaper that suggested that it might be cheaper to tear down the Eiffel Tower than to repair it, Lustig brought in several scrap iron dealers to a hotel room for a secret meeting, and claimed to them that the French government had officially decided to turn the Eiffel Tower into scrap metal. Lustig additionally claimed that he was a government worker who was willing to secure the scrap metal in advance, before the tear-down supposedly became public.

Unfortunately, scrap metal dealer André Poisson fell for Lustig's con and paid him $70,000, equivalent to over $1 million in 2023, and Lustig fled to Austria before Poisson could figure out what had happened. And because Poisson never reported the crime to the police — likely because he was embarrassed — Lustig got cocky enough to try again. Within half a year, Lustig returned to Paris and once again tried to swindle someone into buying the Eiffel Tower from him. This time, though, the fraud was reported, and Lustig was forced to flee to the United States. But although Lustig's con was revealed, the hapless scrap metal dealer Poisson never saw his $70,000 again.

The Santa Claus Bank Robbery

Not all methods of illegally gaining large sums of money quickly are complicated: Some involve simply going into a bank and robbing the place. But one of the notorious bank robberies of the 1920s was the Santa Claus Bank Robbery of 1927, which led to one of the largest manhunts ever in the state of Texas. During the 1920s, robbing a bank was one of Texas' most popular get-rich-quick schemes, But it also became incredibly risky once there was a reward offered of $5,000 – worth more than $80,000 in 2023 – for killing a bank robber.

On December 23, 1927, Marshall Ratliff, Henry Helms, Robert Hill, and Louis Davis robbed the First National Bank in Cisco, Texas, making it out of the bank with over $160,000 worth of cash and valuables. The robbery's name came from the fact that Ratliff entered the bank in a Santa Claus suit as a disguise. But the fact that there was a high reward for killing a bank robber meant that bank customers with a gun were also ready to make some quick cash. So many people fired their guns in the bank, along with the robbers, that police later estimated that there were up to 200 shots fired.

The situation became so hectic that although the four men managed to get away from the scene of the crime, they ended up accidentally leaving the money behind with Davis, who was wounded and died shortly thereafter.