The Most Prolific Con Artists In History

There's an old saying that crime doesn't pay, but history is filled with ridiculously adept con artists who proved time and time again that sometimes, it does. (Until, of course, they're caught.) There's another old saying that applies here: Go big or go home.

Look at the story of Gregor MacGregor. He, says the BBC, announced in 1822 that he wasn't just a perfectly ordinary, longtime resident of Glengyle, Scotland, but he was also a prince (or, he claimed, Cazique) of a mysterious, far-away land near Honduras. His true home of Poyais was nothing short of magical, he said, with rivers lined with gold, forests filled with exotic fruits and animals, and bountiful harvests. Sounds too good to be true? It was, but he still managed to convince scores of people to invest in turning the country into a Scottish colony and building the infrastructure needed to make the most out of Poyais's bounty. They were, of course, investing in Gregor MacGregor — to the tune of about $4.8 billion in today's money (USD). While it's easy to point and laugh with the advantage of hindsight, people are still falling for the scams of con artists today.

Psychologists call it the approach-avoidance model of persuasion, and it essentially states that if you try to convince people of something that they already want to believe in, it's not really that hard. And these con artists convinced people to believe on a shocking scale.

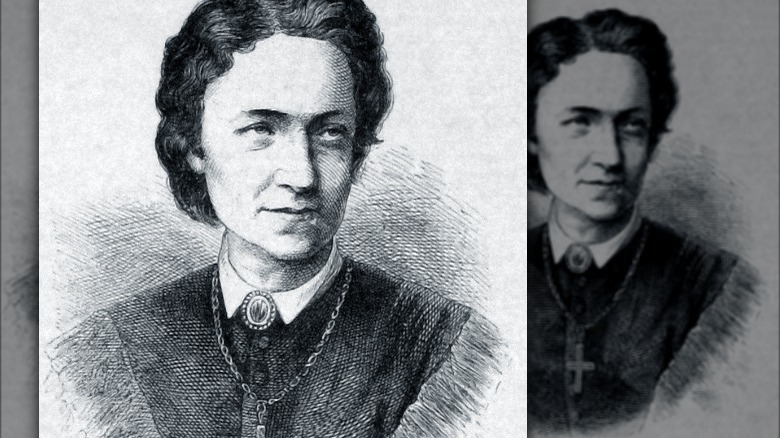

Adelheid Spitzeder

Adelheid Spitzeder made her acting debut in 1856 but quickly fell into the "starving artist" category of entertainers. Penniless by 1869, Spitzeder started out her secondary career by borrowing 100 guilden and promising that she was going to pay it back with an interest rate of 10% per month. She then continued to borrow money with a promise to pay it back at a high interest rate, eventually opening her own bank to carry out the transactions, and employing around 40 people to handle all her clients. According to Money Week, she was so wildly successful that by 1872, she had become Bavaria's richest woman.

If that sounds like a Ponzi scheme, that's because it absolutely is. BR says that Spitzeder's borrowing-to-pay-others scheme is the first large-scale Ponzi scheme ever run, and yes, it collapsed on her.

Authorities were asking questions by around 1871, and Spitzeder spent much of her time defending herself against the naysayers. (At one point, she even claimed she was being threatened by the infamous, mysterious, "Jewish cabal.") It didn't work for long: Customers withdrew their money, much of it wasn't there, and even as she was put on trial and sentenced to several years in jail, her wine cellars, art collections, and the other trappings of her extravagant lifestyle were sent to auction. She had taken the equivalent of $206 million USD from 32,000 people, and after she was released, she became a folk singer and died in 1895.

William Chaloner

According to Headstuff, William Chaloner was a failed nail-maker turned coin counterfeiter, and he was really good at what was called "tongue pudding." In other words, he was an incredible salesman who could convince people to buy things that were probably fake, stolen, 100% quackery, or all of the above. In addition to supplementing his ill-gotten income with counterfeiting, he also ran a series of audacious schemes that involved setting people up to do illegal things, then turning them in to the authorities and collecting the reward money. That started with paying four men to print copies of a pamphlet condemning King William, then telling the police all about it. The men were sentenced to death, and he walked away with a cool £1000 ... and this was in 1693.

He was so good at "finding" Jacobite supporters that the British government paid him to do exactly that — and in 1694, he decided to "offer" his "services" to the Mint, and put in place a series of reforms meant to stop those dirty, no-good counterfeiters, who were taking advantage of those incompetent louts in charge.

And that's where his problems started. IRSC says that the Warden of the Mint at the time — who Chaloner ridiculed in a series of pamphlets — was none other than Sir Isaac Newton. Newton launched a massive investigation into what Chaloner was really about, and once the truth came out, Chaloner was arrested. Then, on March 22, 1699, he was sent to the gallows.

Elizabeth Bigley/Cassie Chadwick

The Smithsonian says that Elizabeth Bigley found her calling when she was 13 years old. That's when she developed her first con: She wrote a series of letters saying that she'd gotten an inheritance from an uncle, and presented them to a local bank. That bank gave her checks, and she'd already spent the money by the time they realized there was no actual inheritance.

She perfected the whole thing over the next few years, and in 1879 — now 22 years old — she headed to the big city of London, Ontario. There, she would present stores with documentation of her incoming inheritance, then make a purchase. The bad checks she wrote were for more than the price, and store owners were happy to accommodate the young heiress with some cash back.

Over the following years, Bigley ran all kinds of scams. From pretending to be psychic to marrying and using her new husband's property as collateral for loans, she remained a huge fan of the heiress routine — and in 1903, she went big: Now calling herself Cassie Chadwick, she claimed she was the illegitimate daughter of Andrew Carnegie. Using forged promissory notes supposedly from Carnegie, she secured thousands of dollars in bank loans from New York to Ohio, and by the time law enforcement caught up to her, she had scammed somewhere around $16.5 million in today's money. She was ultimately found guilty of conspiracy and fraud, and was sent to jail.

Philip Arnold and John Slack

The Smithsonian calls it "The Great Diamond Hoax of 1872," and it was an insanely ambitious scheme hatched by two Kentucky grifters named John Slack and Philip Arnold. Arnold was a bookkeeper for San Francisco's Diamond Drill Co., and hit on the idea of promising people they could be the ones to profit from the West's untapped resources... for just a low, low investment. The proof? Arnold secured that, acquiring a fistful of uncut (and likely stolen) diamonds.

Arnold and Slack cast their line by targeting a businessman named George D. Roberts, and first "accidentally" admitting that they knew where to mine a ton of diamonds, and then making him promise not to tell a soul — which, of course, he promptly did. Word about the pair's alleged diamond find spread like wildfire, and it wasn't long before scores of the rich and powerful were involved in financing the exploration and development of the non-existent patch of diamond-rich land.

After taking their marks out to a patch of land seeded with more precious gems, they collected their investments and bailed. While Slack headed off into the wild blue yonder never to be seen again, Arnold sold his share of the "mine," and skipped town — all in all, Arnold alone made an estimated $8 million in today's money. He was indicted for fraud, but the charges were dropped by embarrassed investors. He was 49 years old when he was killed in a shootout, leaving behind a family well provided for.

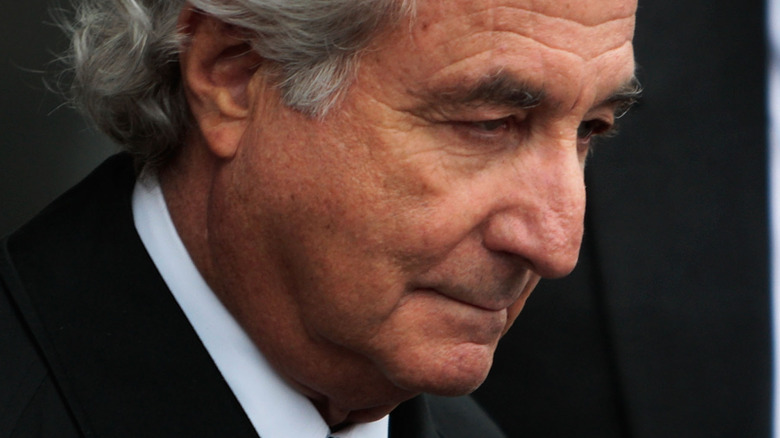

Bernie Madoff

After Bernie Madoff's death in April of 2021, Fortune took a look back at his career — and they found some weird things. Madoff had once described himself as a "people pleaser," and while it's undeniable that he ruined the lives of around 11,000 people with a scam that involved around $65 million (via CNN), it all started because he couldn't bear to tell people he'd lost their money. In 1962, Madoff took on 24 people to start off his career as an investment manager, and when he lost their money, he didn't want to tell family members and close friends that they were broke. Instead, he borrowed $30,000, repaid his initial investors, then went on to have to repay that $30,000 loan — which, incidentally, came from his father-in-law.

Madoff continued to do the same thing over and over again, on an increasingly massive scale. Investors bought stocks through his company and were kept happy by being paid money not from their own accounts or investments, but from the pockets of new investors. The BBC says that the whole shaky tower came toppling down in 2008, when investors panicked by an international recession tried to withdraw around $7 billion at the same time — and it just wasn't there. He was turned in to authorities by his sons, and sentenced to 150 years in jail.

Among Madoff's victims was Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel, who invested with him through his charitable foundation, and lost around $15.2 million (via The Guardian).

Therese Humbert

Therese Humbert may have been born poor, but she had a rich family member in her cousin, Frederic Humbert. She enthralled him with a tale that she had inherited a castle from her mother's recently-dead lover, and by this time, Therese had already been dabbling in scams, says Ouest France. Historian (and author of La Grande Therese) Hilary Spurling says (via The New York Times) that once Frederic realized she was lying, he hopped on board with the whole thing — especially after they were able to leverage the imaginary castle for a very real bank loan, and then buy an equally real castle.

Amid the little schemes, there was one massive one. The Humberts invented a man named Robert Henry Crawford, and claimed he left behind two wills. One left his fortune to Therese, and the other to his nephews. She, however, also claimed that she had secured a promise from the nephews that for the low, low price of just six million francs — along with the hand of Therese's sister in marriage — they would withdraw their claim to their uncle's fortune.

Therese and her husband used the fictional documents to raise money from a series of investors, all the while promising to pay them back when the estate was settled and they came into the really big money. There was, of course, no such money, and after attempting to flee Paris ahead of an angry mob, they were arrested, tried, sentenced to five years, released, and disappeared.

Victor Lustig

Victor Lustig (center) had an arsenal of five languages, 47 aliases, and an undeniable air of aristocracy. According to the Smithsonian, no one's sure exactly who he was, but he claimed to have been born in Austria-Hungary in 1890. He got his start traveling on ocean liners and schmoozing with the rich in order to sell them a "money box" — a counterfeiting device of his own making — for an exorbitant amount of money. The box didn't work, of course, but by the time the buyer realized it, Lustig was long gone.

His most ambitious con came in Paris in 1925. The Eiffel Tower wasn't always the landmark is it today, and at the time, the city was debating about whether or not the maintenance on the structure was a worthwhile expense. Lustig set himself up as a government official looking at just how much a scrap metal dealer might pay for the 7,000 tons of metal. He found out: He sold it for $70,000, then left the country before anyone realized it was a scam.

Lustig eventually ended up in the U.S. and was well-known to law enforcement in about 40 cities before his eventual capture by the Secret Service. He ran everything from real estate scams to a repeat of his money box, and it was so widespread that it was feared his fake money would destabilize the economy. He was ultimately arrested and sent first to Alcatraz, then to a medical facility in Missouri, where he died in 1947.

Frank Abagnale

Frank Abagnale is the con man immortalized by Leonardo DiCaprio in Steven Spielberg's film Catch Me If You Can, and here's the thing: This story isn't going to go in a direction that anyone could have predicted. First, a quick recap, with help from Biography: Abagnale was born in 1948, and always said that he had gotten into a life of crime pretty young. It started with credit cards, escalated into writing scores of bad checks, and then, he hit on the idea of impersonating a Pan Am pilot to not only get some serious cred with the banks he was defrauding, but to fly free all around the world. When people started to get suspicious about that, he decided to become a doctor — and he did, getting a job and even bluffing his way through working at a hospital. Abagnale was eventually arrested, then was hired as a consultant by the FBI.

But here's the thing: Journalist Alan C. Logan did some fact-checking on Abagnale's self-reported life story, and says (via Esquire) that the only conning he did was convincing people any of it was true.

Take the story about being a pilot. Logan says the truth is that he basically dressed up like a pilot to stalk a flight attendant, and it only lasted for a few weeks. His claims that he spent four years dodging the FBI? Logan says he was in jail at the time. So what part is the real con?

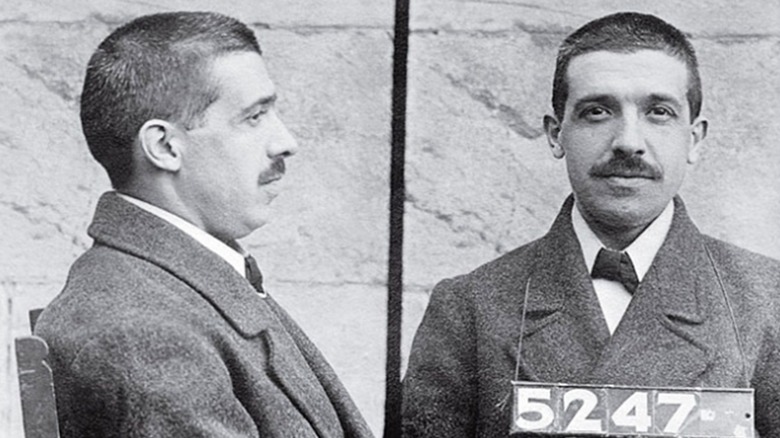

Charles Ponzi

Charles Ponzi didn't invent the grift known as the Ponzi scheme, but he did give his name to the disturbingly popular concept. So, who was he? Ponzi emigrated to the U.S. from Italy in 1903, says Biography, and after a stint in a Canadian prison for writing bad checks, he hopped back across the border to Boston, married, and — while working a series of short-lived odd jobs — came up with his scheme.

It was based around international reply coupons, or IRCs. IRCs were basically prepaid postage that could be exchanged for another country's postage, then that stamp could be sold for more than the purchase value of the original coupon. Ponzi landed on the idea of buying IRCs from outside the U.S., then buying U.S. stamps, and selling those stamps for a profit.

It worked so well — with some, he scored a markup of about 400% — that he started recruiting others to invest. Promised an insane return on their investment, they would put money into the program and Ponzi would pay their profits out from the capital invested by others. It wasn't long before the stamps just weren't necessary at all, and when the bottom fell out of his plan, the Smithsonian says that he had just $61 in IRCs to his name. Meanwhile, he had a network of 40,000 investors and a personal net worth of around $8.5 million. Ponzi was convicted, sent to jail, and died in Brazil in 1949. At his death, he was penniless.

Sarah Russell

Historian and author Helen Rappaport wrote "Beautiful For Ever" about the life of a con artist born in the East End of London as Sarah Russell. She grew up in a Victorian Era where makeup, hair dyes, and anti-aging creams were only for sex workers and the theater, but she knew she could change that, so she set about doing precisely that.

Reinventing herself as Madame Rachel, Russell sold all kinds of potions, tonics, tinctures, and powders, all claiming to work some serious miracles. And the upper-class ladies of London society were all willing to spend a shocking amount of money on her range of products, which included around 60 different concoctions that she claimed were formulated from the secret recipes used by the eternally youthful harem girls of ancient Arabia. They all had exotic names — like the Honey of Mount Hymettus soap — which was enough to disguise the fact that they were definitely not exotic. Most were made from perfectly ordinary — and oftentimes deadly — ingredients sourced right from London, including arsenic, lead, and corrosive sublimate.

In addition, she also sold an "enamelling" service, which cost just over $2,000 USD in today's money, and reportedly made the skin whiter and blemish-free. Did it? That's debatable, and Madame Rachel did debate it — twice, in court, after which she served two prison sentences and maintained that she really did know the secret to eternal beauty. She died in 1880, still in prison.

Amy Bock

Amy Bock's parents encouraged her interest in the theater, says Headstuff, and there's no way they could have known she would eventually put that interest to good use and become New Zealand's most notorious con artist. Initially making a living as a teacher, Bock eventually started running a variety of scams. From buying big-ticket items on credit then selling them for a profit to asking to "borrow" items then simply walking off with them, she was wildly prolific when it came to the con. She defrauded those who hired her as a governess, cook, or housekeeper, mortgaged or pawned employers' property, and talked her way out of trouble with surprising success. And then, she became Percy Redwood.

Redwood, the story went, was a wealthy sheep farmer who was on vacation when he happened to fall in love with Agnes Ottaway. Feelings were reciprocated, and the two were married. But, it was a small town in 1909, and people were naturally suspicious of this outsider. Their suspicions were confirmed, and Bock was arrested, sentenced, and released in 1912. She continued her habit of conning anyone she could out of some cash, and by the time she died in 1943, her shenanigans had ceased to be as news-worthy as they once were.

There is, however, a fascinating footnote that comes via RNZ. When Bock was 10, her mother was institutionalized for what's now called bipolar disorder — and Bock spent her career using her mother's mental illness as a crutch for her own behavior.

Christopher Rocancourt

George Mueller was law enforcement with the Los Angeles district attorney's office when he found himself chasing the man only occasionally known by what seemed the most likely to be his real name: Christopher Rocancourt. Some knew him as Christopher Reyes — husband to former Playboy playmate Pia Reyes — while others gave his last name as Rockefeller, De Laurentiis, or de la Renta. That's because, says Vanity Fair, he was exceptionally good at claiming to be related to the rich and famous, then using his reported fame to con actual rich and famous people out of millions.

The list of crimes he's associated with is almost ridiculous in terms of sheer audacity. From smuggling diamonds in Zaire to a proposed perfume deal with Jermaine and Michael Jackson, from taking millions with promises to invest, to even convincing Jean-Claude Van Damme to work with him as a film producer, it's the sort of life story that just gets more and more unbelievable.

According to The Local, Rocancourt started big: In the 1980s, he forged the deed to a property and sold it for a hefty $1.4 million ... and no, he definitely didn't own it. Arrests, convictions, and jail time didn't dissuade him, either. Even after he was released, he was right back at it: In 2009, he was accused of taking Catherine Breillat — a French director diagnosed with cerebrovascular disease — for around $800,000.

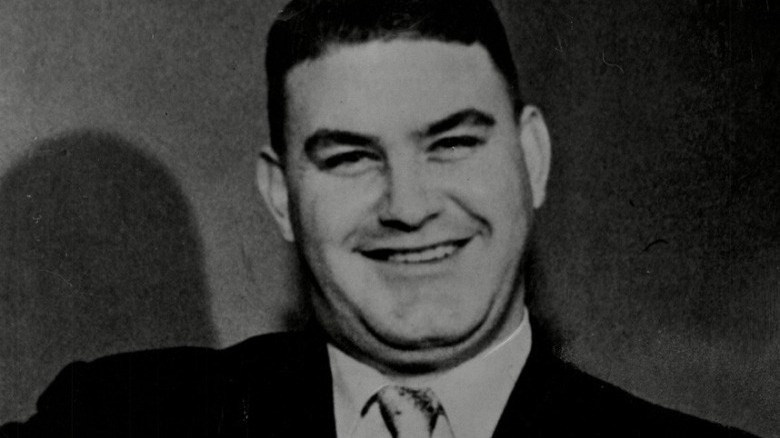

Ferdinand Waldo Demara

The story of Ferdinand Waldo Demara is a little different from that of most con artists. While money is a motivator for countless cons, Bangor University lecturer in criminology Tim Holmes says (via the Independent) that Demara wanted something else: He wanted to be noticed, congratulated, and to be treated like he was someone important.

Unfortunately for Demara, he didn't have the patience to actually put in the work to get the accolades, so he faked it. His 23-year-long career of "fake it until you make it" professions started when he decided to be a Trappist monk, but got kicked out of the monastery. From there it was into the military, and when he decided he wanted to become a doctor, he just sort of forged all the paperwork he needed to do so. He spent some time teaching college as a psychologist, then decided to give himself some PhDs to become a doctor — and he did, serving in the Korean War as a commissioned officer. He even did some operations — while referring to some textbooks for guidance — but his real identity surfaced when he was lauded in the press for his heroism.

Demara's life was ultimately used as the blueprint for the Tony Curtis movie "The Great Imposter," but Demara always claimed the whole thing was exaggerated. Was it? Not according to his obituary in The New York Times: Demara died in 1982 at just 60 years old, having lived more lives than most people ever even dream of.

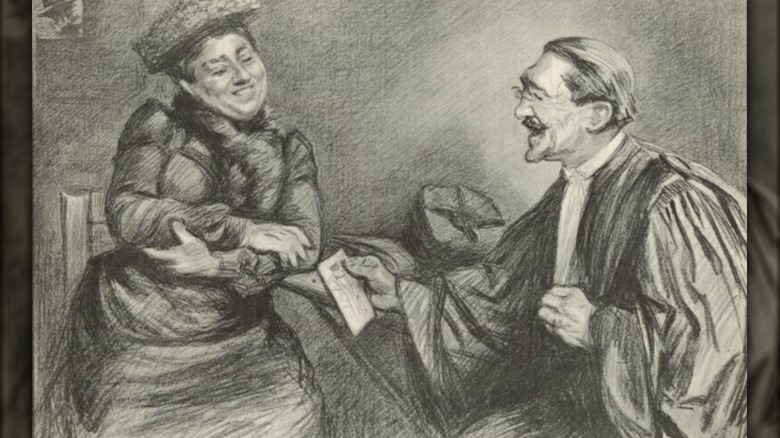

Bertha Heyman

Bertha Heyman definitely had a type, says historian and author Geri Walton, and it was men. The Prussian-born Heyman found herself on American soil in 1861, and she made a massive splash with her favorite swindle. She would play the part of a wealthy woman with a problem — she needed just a little bit of cash in order to access her own funds. She was so successful she was soon given the title of "Confidence Queen," and by the time the Pinkertons caught up with her, she had left behind a slew of very disappointed men who were thousands of dollars poorer.

But that wasn't the end of the story.

She was behind bars in 1883, but still managed to convince a man named Charles Karpe to send her so much money that he ended up penniless. Once she was released, she ended up going back to her old ways, and after another stint in jail, she caught the attention of Ned Foster, a theater man. According to the San Francisco Examiner, she was a huge hit on-stage, where thousands of people flocked to see her lament her misfortunes: She was, she claimed, the victim in this whole thing. She participated in staged boxing matches and a comedic version of Romeo and Juliet, until she scammed Foster, too.

She explained: "The moment I discover a man's a fool, I let him drop, but I delight in getting into the confidence and pockets of men who think they can't be skinned. It ministers to my intellectual pride."