Wendigos: The Myth Of The Terrifying Beasts Explained

The odds are pretty good that at some point in your life, you've been gathered around a campfire with friends trading stories about all the specters and monstrosities that could lurk out of the woods and consume your supple young flesh bits. There's the Hook Handed Man, an American classic. There are ravenous cryptids, reported secondhand but never captured on film, like Bigfoot and werewolves and the chupacabra and the small vampire that controls Mark Zuckerburg's steam-powered skin suit. And of course, there's the Wendigo.

Stories about the Wendigo have been told for centuries, echoing fears of humanity's darkest potential. Like all of the best beasts of folklore, it strikes up visceral images of the possibilities we all know are out there but lock away in the backs of our minds. In the northern wilderness, when you're all alone and miles from civilization, it can probably seem like this supernatural night terror could be anywhere. It could lurk behind any tree, or watch hungrily from any shadow, waiting to end you, unwitnessed, in unspeakably haunting ways.

What sorts of unspeakably haunting ways are we talking about? Let's explore the tale of the Wendigo.

The myth of the Wendigo

So what, you might well ask, is the Wendigo?

According to legend, the Wendigo could be one of two things. The first possibility is that it's a physical being; a hideous monster that stalks the northern woods, desperate to sate its unfathomable hunger. Different stories described it differently. Sometimes it had the head of a stag, and other times it was closer to a monstrous human, emaciated from constantly starving. It was sometimes said to grow in proportion to the size of the meal it had just consumed, making it impossible for the beast to ever eat its fill. In a particularly jarring description from Ojibwe scholar Basil Johnston, its lips were described as "tattered" and it was said that it smelled like "death and corruption."

In other stories, a Wendigo is a malevolent spirit that takes control of men's bodies, cursing them with an incurable need to consume human flesh. It was said that this spirit could possess a person who was overcome with selfishness or greed, leading them to acts of cannibalism. This sort of storytelling is mirrored in the folklore of other cultures: If you don't behave then Krampus will take you, and if you're too self-involved, you'll become a man-eating forest ghoul.

The folklore behind the Wendigo

Like many cryptozoological monstrosities, the Wendigo has its roots in a variety of cultures. It originates in the northern regions of North America with the folklore of the Algonquian indigenous peoples.

The term "Algonquian" in this case refers less to a single tribe of Native Americans and more to a subset of cultures based mostly around Canada, the Northeast U.S. coast, and the Great Lakes regions. Among the dozens of tribes included in the blanket definition are the Cree, Ojibwe, and Innu. Many of these societies shared similar dialects and, importantly, the life experiences inherent in a life spent in the punishing climate of the North. Starvation and exposure to the elements were very real dangers, and as with any culture, fears gave birth to stories and mythological personifications of possible threats. In the same way that concerns about the destructive potential of nuclear technology brought Godzilla to the modern world, a very real fear of desperation may have led to the proliferation of stories about the Wendigo. Different groups had different variations on the mythos, but one thing always stayed the same: the all-consuming hunger that drove it to take the lives of the unwary.

What to expect when you're expecting (to be eaten by a Wendigo)

So you're out in the frigid wilderness of the North American woods when you happen across a Wendigo. Your first reaction might be to panic, and maybe even give up on any chance of having a pleasant afternoon. But is that reasonable?

According to legends, yes. Stories tell us that a Wendigo is almost impossible to escape. They are relentless in their pursuit of food and unaffected by the punishing elements. On their home turf, the unforgiving cold in the forests of the North, you're pretty much out of luck. Some sources say you're no better off if you make it to shelter since the Wendigo, like the humble velociraptor, has no trouble opening doors. Wherever you go, the creature will follow, raking at you with grasping claws, tirelessly pursuing the despairing hope that you will be the meal that finally gives it satisfaction.

Oh, it's also worth mentioning that even if you do escape, you'll probably lose your mind. There really isn't such thing as a "glass is half full" Wendigo encounter.

Preparedness is key

The good news is that there are stories describing ways to kill a Wendigo. The bad news is that you're going to need a lot of silver.

The chief weakness of a Wendigo, traditionally, is its heart. The beast reportedly has a ticker made of solid ice, which, while probably great when it doesn't want to make a cooler run at a barbecue, leaves it vulnerable to a rare form of violence we'll call "heart smashery." According to howstuffworks, if you can get at the creature's heart with a silver blade or stake or bullet, then shatter the heart, then put the shattered heart bits in a silver box, then lock the box, and finally bury the box in a graveyard, then maybe, just MAYBE, the Wendigo will die. The folks at mythology.net add a few steps like dismembering and cremating the body and scattering its ashes in several directions.

The best way to win a fight with a Wendigo, though, is to avoid a Wendigo altogether. To accomplish this, it's recommended that you keep a roaring fire going to dissuade the icy monster. Barring this, there are always amulets and charms.

Wendigo psychosis

Every so often, a mythological creature will become so iconic that a medical condition will be named after it. The chimera lends its name to genetic chimerism, in which a human being has more than one set of DNA. We get the word "phobia" from Phobos, the Greek personification of fear. Narcissism, hermaphroditism, and Proteus syndrome all come from ancient mythology. The Wendigo, too, has a namesake, and as you might expect, it's downright unpleasant.

Wendigo psychosis is a fascinating condition with a storied history. It's a term for what happens to people who for one reason or another turn to eating other people. Shock factor aside, it's especially eye-catching in that it isn't necessarily a result of being desperate for food. In fact, some of the most famous cases of Wendigo psychosis seem to have sprung up for no reason at all. Whether it's an actual psychiatric condition or the result of culturally embedded fears taking hold of people is a matter of debate, but the stories are gripping.

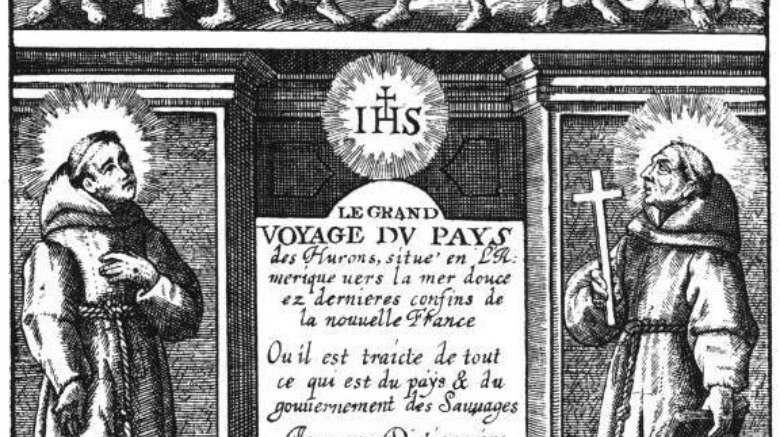

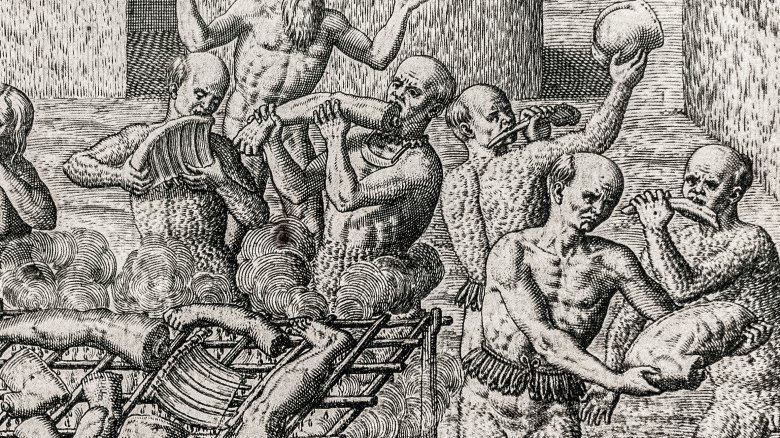

The Jesuit Relations

For just over 40 years in the 1600s, a group of French missionaries of the Jesuit order traveled through New France, a wide swath of North America that is now comprised of Montreal, Quebec, and regions of the United States acquired during the Louisiana Purchase. On this mission, the men of the cloth interacted with the indigenous people, hoping to spread Catholicism. They published stories of their encounters in a series of books called Relations des Jésuites de la Nouvelle-France, or The Jesuit Relations, which they used to spread word of their work and attract financial backing.

In a particularly horrific passage, the Jesuits described the ill fate that befell a group of men they were supposed to meet. Reportedly, they had been overcome with a mysterious psychosis, which they described in detail: "(They become) so ravenous for human flesh that they pounce upon women, children, and even upon men, like veritable werewolves, and devour them voraciously, without being able to appease or glut their appetite — ever seeking fresh prey, and the more greedily the more they eat."

The account continues, and we're told that the afflicted men had to be executed as this was the only cure for their condition. It's one of the first Western accounts of Wendigo psychosis in action, and it's also tied with every German fairy tale for "worst bedtime story ever written."

The hunger of Swift Runner

According to the Edmonton Journal, the man known as Swift Runner was generally well liked for a while. He was a member of the Cree tribe, and he had worked as a guide for the local mounted police. But toward the end of 1878, he took his family into the woods and walked into macabre history.

The next time he was seen in public was in the spring of 1879. He claimed that his entire family, including his wife and six children, had died of starvation during the harsh winter months. The police at Fort Saskatchewan, however, couldn't help but notice that the man himself didn't look like he had missed a meal. They investigated his campsite and discovered grisly remains: bones picked clean of meat, some with the marrow hollowed out. A skull with a shoe jammed inside. When confronted about the crime, Swift Runner confessed to having killed and eaten his family.

Swift Runner's story went on to become the go-to example of Wendigo psychosis since it's believed that he had ready access to means of survival besides slaughtering and consuming his entire family. The full truth will probably never be known, and the world's most famous Wendigo was executed in late 1879 in Alberta's first government-sanctioned hanging.

Jack the monster slayer

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, there was a member of the Sandy Lake First Nation named Zhauwuno-geezhigo-gaubow. Known to the Europeans in the area as "Jack Fiddler," he was a shaman, a holy healer with a particularly sought-after skill set: Jack could fight Wendigos.

Jack claimed to have stopped as many as 14 Wendigos in his life. His method? Euthanization. When people felt the curse of the Wendigo beginning to overpower them, they would send for the holy man to end their misery before they could do any real damage, safe being better than sorry.

As it was the turn of the century, tribal traditions were beginning to go by the wayside, and when the Canadian government got wind of a mystical cannibal fighter, they didn't much cotton to the idea of spiritual medicine by way of execution. Mounties were sent to investigate and discovered a woman who had been strangled to death in order to pull the people-eating spirit out of her. Jack and his brother were arrested for murder. Before he could be executed, the shaman escaped from jail and killed himself.

Dead is better

If you're one of the millions of people across the world who love Stephen King movies but lack a compulsion to see modern remakes and the Olympic-level attention span required to read his uniformly way-too-thick books, you might not be aware that the Wendigo plays a pivotal role in one of his most famous horror stories.

In Pet Sematary, an upper middle-class family moves into a big, creepy house in a small Americana town, as is the wont of upper middle-class families in horror stories. Through their friendship with a local alcoholic and a series of merry mix-ups, they discover that they're living within spitting distance of a Micmac burial ground, abandoned by the natives because "the ground was sour." In the 1989 movie adaptation, the combination of a woodsy area and vaguely defined spiritualism was enough of an explanation to get audiences from A to B, narratively speaking, but in the book, there's cannibal monster chicanery afoot to boot.

Yes, the spirit of the Wendigo is what drives the actions of the undead in Pet Sematary. You know, because that narrative wasn't creepy enough.

The Wendigo helped bring us Wolverine

For all of the evil attributed to the Wendigo throughout history, at least a little good has come from it: It indirectly contributed to keeping Hugh Jackman employed for the better part of two decades. Starting in the '70s, Marvel Comics co-opted the Wendigo legend, taking myths about a bone-thin forest demon and subtly sculpting them into a comic book villain, 8 feet tall and covered in muscle. The Wendigo served as a Hulk antagonist, a man cursed with primal hunger after committing an act of cannibalism in the Canadian wilderness.

It was during a Hulk v. Wendigo donnybrook that Wolverine made his first appearance. The scrappy little dude still had a significant amount of rebranding to do before he would become a household name (he had whiskers at the time), but he managed to down the Wendigo without using any silver at all, which must've taken some effort.

So there you have it: The Wendigo is technically part of the same universe as Iron Man. No word on when he'll be getting his own movie, or how the MCU would square having a flesh-eating death demon in the same cinematic universe as, say, Baby Groot, but they've made weirder things work.

The Wendigo across pop culture

In much the same way that the spirit of the Wendigo lurks in the corners of the forest, its presence can also be felt across swaths of popular culture. They've appeared in more than their fair share of B-movies, as well as episodes of shows like Charmed and Supernatural.

Creep monster that it is, the Wendigo also makes a great target in the world of gaming. They're the (spoiler alert) main bad guys in 2015's Until Dawn. Most recently, they appeared in Fallout 76 as the hideous result of radiation-based mutation, featuring otherworldly, stretched-out bodies, acid-laced teeth, and potbellies waiting to be filled with delicious wasteland wanderer giblets. There's even a mission where the player is tasked with killing one while dressed as a clown because who the hell knows what's going on with that game.

And for fans of adding a little bit of horror show nightmarishness to their kid-friendly cartoon gaming, take comfort in the fact that the maneater from the North can be adorably summoned in the Scribblenauts franchise. Horrifying.

The Wendigo won't be coming alone

No matter what your thing is, it's nice to know that there are other folks out there who share the same interests. Lucky for the Wendigo, it's far from the only cannibalistic night-sweat inducer on the field.

There are Iroquois and Seneca legends, for example, that tell the story of the Flying Head. The Flying Head is a giant, you guessed it, flying head, said to be taller than a man and hungry for human flesh. In some stories, it's the cursed head of a murder victim, out for delicious anthropophagus revenge. In other tellings, it's the fate that awaits people who turn to cannibalism in the first place. Many of the Athabaskan tribes indigenous to Alaska, British Columbia, and the Pacific Northwest told stories about the Wechuge, another man-eater, said to be the result of a person being overpowered by old, powerful spirit animals. And what list of human/monster amalgams that will devour you in your sleep would be complete without fan favorite Baba Yaga, the occasionally friendly Slavic forest witch who lives in a chicken-legged hut and probably thinks you're delectable.

So to sum up, the good news is that the Wendigo probably isn't real. The bad news is that, according to the law of averages, one of the other dozen or so cannibal monsters out there might be and, statistically, it's standing right behind you.

Wendigos vs Wechuges

While the Wendigo is rapidly becoming a major player in the modern horror genre, it is certainly not the only sinister creature that supposedly lurked in the cold darkness of North America. Stretching into the farthest reaches of what is today Alaska and Canada up to the borders of the artic, the native Athabaskan people of the region have also spread horrifying tales over the centuries of a monstrous figure similar to the notorious fiend that terrorized their southern neighbors.

Essentially, the Wechuge is a less well-known Athabaskan version of the Algonquian Wendigo, but with some key differences, according to David D. Gilmore in his book, "Monsters: Evil Beings, Mythical Beasts, and All Manner of Imaginary Terrors." Wechuges can be just as vicious as Wendigos but are not as powerful or hideous in appearance. Therefore, the northern monsters are far more likely to use deception and guile in order to ensnare their human prey for dinner. An utterly unsettling reason why Wechuges were so successful at tricking their victims was that the creatures are said to be nearly indistinguishable from a person aside from a few savage aspects of their appearance, such as wild eyes, sharp teeth, and mangled, bloody lips.

On the other hand, the Wechuge has organs composed of ice, just like the Wendigo. So, both monsters can be slain the same way — first with fire to melt the frozen innards of the fiends, followed by the removal of the head.

Wendigos are said to be able to mimic human voices

As huge, beastlike brutes that crave human flesh, the Wendigo is scary enough, but it also has an extraordinary ability that makes the creature even more terrifying. In his book, "Dangerous Spirits: The Windigo in Myth and History," Shawn Smallman says that in the Native American oral traditions passed down through the generations, Wendigos had the creepy power to imitate the speech of a human being.

According to legends, the Wendigo's horrifying skill is far more impressive than, say, a parrot, and the monster has used its mimicry in the past to lure victims away from the safety of their homes. But in his article, "Incursion Into Wendigo Territory," Jackson Eflin takes the seemingly supernatural aspect of the monster a step further and explains that in some of the ancient stories, Wendigos were almost like shape-shifters and could even change their face to that of another person.

Native American legends associated Wendigos with owls

In 2021, the success of the horror hit, "Antlers," has helped considerably in making Wendigos more widespread in popular culture. However, the creature feature is also responsible in a massive way for perpetuating a false interpretation of what the legendary monster looked like. According to the PBS series "Monstrum," there is not a single Algonquian myth that ever describes the Wendigo with antlers, horns, or any other trait like that.

Instead, the depiction of Wendigos with stag-like features is purely a modern creation. On top of the early 20th-century novella "The Wendigo" by Algernon Blackwood, the far more recent film — 2001's "Wendigo" — was one of the first to show the creature in that inaccurate form nearly 100 years later. Ever since then, Hollywood has run wild with the concept and depicted Wendigos with antlers in several other horror productions like the remake of "Pet Semetary" and in the series "Hannibal" (above).

On the other hand, the Native American tales did associate their nightmarish fiend with an animal — it just wasn't stags. In fact, while the indigenous term, "Windigo," often meant "cannibal," there were also dialects in which the word was more accurately translated as "owl," a creature of the night.

Reported sightings of Wendigos

Following the Jesuit accounts of the 17th century, there have been numerous reports of supposed Wendigo sightings for over three hundred years, including the writings of a Frenchman in the 1720s and then English explorer Henry Ellis in 1748. Both individuals had direct contact with indigenous people who firmly believed in the existence of the regional monster, says David D. Gilmore in his book, "Monsters: Evil Beings, Mythical Beasts, and All Manner of Imaginary Terrors."

The deep fear has persisted into the modern period — as recently as 1950, a community of over 1,000 Saulteaux people was thrown into chaos over the belief that the monster was on the prowl once again. To this day, people in the north continue to claim they have seen or heard the creatures, and that has spread beyond just the native populations.

In 2004, one of these witnesses, June Stevens, went public after she came across an animal that she had never seen or heard of before. Stevens said (via the Sun Journal), "It appeared larger than a dog, had a bristly looking coat, sort of a mottle gray and black. It was not a bit timid, started right at us." Cryptozoologist Michael de Sackville has been skeptical about much of the various claims, but also theorizes that sightings of potential Wendigos "may be a rare form of wolverine that supposedly became extinct during the last Ice Age."