Incredible Archaeological Finds That Changed Everything

If all the world's still-hidden archaeological sites were revealed to us right now, they still wouldn't tell us everything there is to know about human history. We'd need a time machine for that. The only thing those still-hidden sites could do for us is provide tantalizing clues about what life was like before people started writing everything down (and after they started lying about all the things they were writing down).

Until we finally figure out how to build that time machine, archaeology is all we have. And over the years, it's given us some pretty amazing information. The world was wowed by the discoveries of King Tut's tomb, the Dead Sea Scrolls, Pompeii, and the Rosetta Stone — archaeological discoveries that changed our understanding of human history. But there are also hundreds of archaeological sites all over the world that are less well-known but equally important. Some of these discoveries may sound familiar, some you may never have heard of at all, but they're all groundbreaking, they're all monumental, and they all, in a sense, rewrote the history books. From hidden cities to mysterious mazes, these incredible archaeological finds changed everything.

A huge city changed how we think about the Stone Age

When you think about the Stone Age, you probably think about cavemen with crude stone tools wearing animal skins and dragging each other around by the hair. You probably don't imagine cities, cemeteries, and agriculture. But Stone Age settlements existed, and one of the biggest was recently unearthed near Motza, Israel. According to the New York Post, the city is 9,000 years old and once housed between 2,000 and 3,000 people, which makes it one of the largest of its kind ever unearthed.

Archaeologists previously believed that the area was uninhabited 9,000 years ago, so the discovery changes what we know about the rise of civilization in the Middle East. And it's not like this is just a big city of caves or anything, either. This is a sophisticated settlement complete with large buildings, back allies, storage sheds full of still-identifiable legumes, and burial places. It's all evidence that the people who lived there weren't just capable of complex planning — they also had sophisticated large-scale agricultural practices.

Archaeologists also found the bones of sheep, which suggests extensive shepherding practices. There were flint tools, too, including axes, arrowheads, and knives. "It's a game changer, a site that will drastically shift what we know about the Neolithic era," excavation co-director Jacob Vardi told The Times of Israel. And it's likely to continue providing us with compelling information for years to come.

A buried ship and a dead king gave us a glimpse of the Anglo-Saxons

In 1934, Edith Pretty decided to excavate the large mounds (or barrows) on her southern England property, known as Sutton Hoo. According to some stories, she'd seen a ghostly procession marching through the mounds, and that was part of what piqued her curiosity. Most of us would, you know, move, but she decided to dig up the area and risk upsetting all those ghosts instead, so kudos.

Anyway, according to National Geographic, a self-taught archaeologist named Basil Brown took the job. Inside the largest mound, he found rust stains and nails placed at regular intervals in the ground, which turned out to be the 80-foot long phantom imprint of a ship. Inside was an undisturbed cache of 263 objects, which included weapons and silver and golden goods like cutlery, buckles, and coins. Plus, there was a totally unique, full-face helmet. The treasure included objects from as far away as the Middle East and the Byzantine Empire, so its discovery gave archaeologists new information about Anglo-Saxon trade networks.

Sutton Hoo was the largest Anglo-Saxon ship burial ever discovered, but archaeologists still don't know who was buried there. They didn't find a body, though that doesn't necessarily mean there never was one. The soil at Sutton Hoo is acidic, so the bones might've decayed away just like the wood of the ship did. Historians do think it was someone important, though, maybe even King Raedwald of East Anglia, who died around the same time as the ship was placed in the earth.

The birthplace of humankind was an archaeological milestone

Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania is barely an archaeological site. Stone tools have been found there, but for the most part, the site is paleoanthropological because its real treasures are the fossilized bones of hominins and other primates.

According to Live Science, Olduvai is named for the wild sisal that grows in the area, which by the way is spelled "Oldupai," so clearly someone didn't have their spell checker turned on. The site was first identified by Louis and Mary Leakey, who found stone tools there in the 1930s. The Leakeys excavated Olduvai off and on for decades, and one of their most significant finds involved the fossilized remains of a small hominin with human-like features that appeared to be a tool-user, which they named Homo habilis, or "handy human."

Homo habilis' place on the human family tree is controversial, though. Later H. habilis skeletons seemed to suggest that the species was more ape-like than human, and some paleoanthropologists think it's more of a human cousin than a direct ancestor. Still, other important fossils were found at Olduvai Gorge, including OH 9, one of the first examples of Homo erectus, which is a more likely (though still unproven) human ancestor.

A hidden library taught us about ancient life

How can a library and most of its contents survive for thousands of years? Well, it helps if the documents aren't made out of paper.

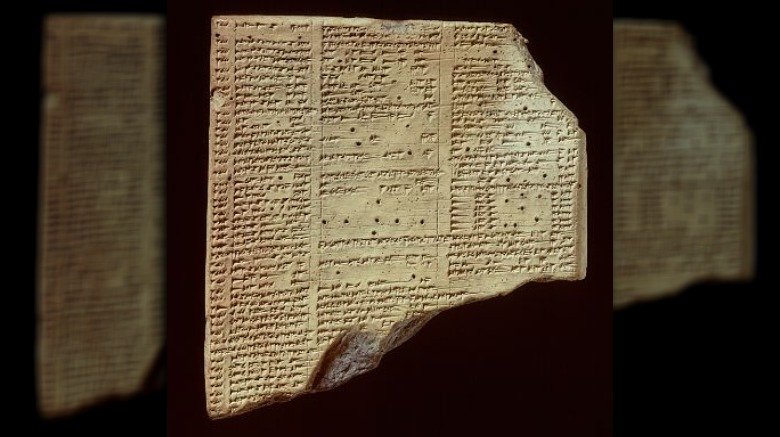

The Library of Ashurbanipal contains 30,000 clay tablets, some of which date all the way back to 721 BC. According to ThoughtCo, the enormous collection belonged to the king who ruled Assyria and Babylonia between 668 and 627 BC. King Ashurbanipal was fascinated with Sumerian and Akkadian cuneiform writing, and he had agents who were specifically tasked with finding old texts, especially those that contained instructions for rituals, protection spells, and purification. They also looked for texts about water control, because they had to know about some practical stuff, too. Ashurbanipal wasn't super-picky, though, and the collection contains works on a broad range of subjects, from medical to lexical to religious and historical.

Archaeologists think the library probably had more than 30,000 documents in it at one time, but some of the materials, like parchment and papyrus, were less permanent and may have been destroyed during the sack of Nineveh in 612. The library of Ashurbanipal lay undisturbed for thousand of years, until it was discovered in the mid-19th century during the excavation of Nineveh. It took roughly 80 years for the British Museum to safely remove all 30,000 tablets.

Neanderthal technology that's still in use today

One of the prevailing theories about the fate of the Neanderthals is that humans wiped them out. And just to add insult to injury, we may have also stolen their tech.

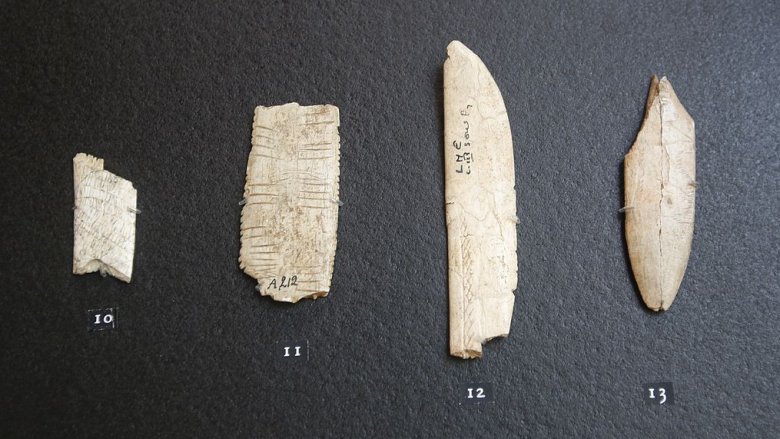

According to The Guardian, in 2005, researchers from Leiden University in the Netherlands found a piece of a lissoir in a cave in southwest France. A lissoir is a tool made from a deer's rib bone, which is used to work animal skins so they'll be tougher, softer, and water-resistant. Leather workers still use similar tools today, though the modern name for them is a "slicker" or a "burnisher."

The site where the lissoir was found was clearly Neanderthal, as there's no evidence of human occupation, and the only remains found all belonged to Neanderthals. The site was also 51,000 years old, which means it predates the arrival of modern human beings by about 6,000 years.

Now, the find could be explained differently depending on how accurate those human arrival dates actually are. Some people think humans may have arrived earlier than we currently believe they did, which could mean that the Neanderthals stole our tech and not the other way around. Or it could just be another example of human beings thinking they're better than everyone else. "Hey Neanderthals, let me humansplain this device to you." Jeez, humans, why don't you go map the flat Earth or something and leave the Neanderthals alone.

The lost city of Vilcabamba changed what we know about the Incas

When Europeans ventured into South and Central America, they were mostly looking for gold ... and the Fountain of Youth. What they found was deadly snakes, spiders the size of their heads, and chocolate. And come on already, who cares about stupid gold treasures when you've just discovered chocolate for the first time?

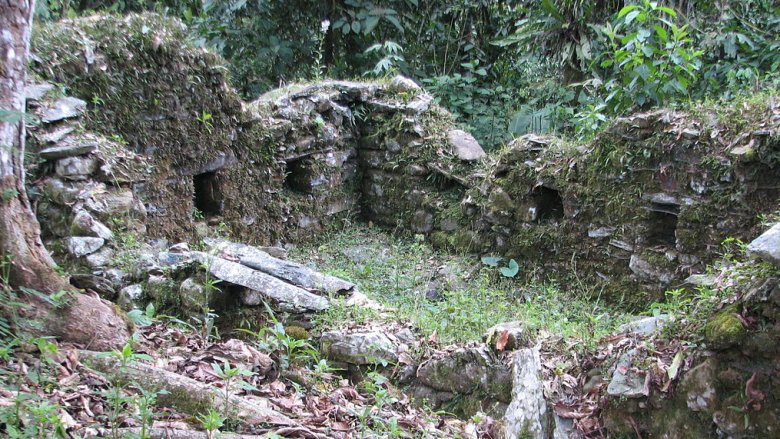

Anyway, by the 1900s, there were explorers looking for more than just gold, silver, and chocolate. According to Britannica, amateur archaeologist and explorer Gene Savoy became interested in South America after reading Hiram Bingham's Lost City of the Incas. In 1964, he discovered Vilcabamba, which was the last stronghold of the Incas during the 16th-century Spanish invasion.

Savoy's discovery was groundbreaking because it disproved a longstanding theory that Machu Picchu and Vilcabamba were the same place. But after Savoy's discovery, the site sort of lingered in anonymity. It was first mapped in the 1980s by an architect and explorer who had to do it under the noses of the Shining Path guerrillas, who occupied the region at the time. Since then, archaeologists have uncovered odd things like scissors, metal nails, and roof tiles — objects that help them understand the people who lived at Vilcabamba hundreds of years ago.

Medieval coins on a newly 'discovered' land

The idea that anyone could really "discover" a land that's been inhabited by humans for 50,000 years is purely and ridiculously European, but let's just go there for a moment so we have the proper set-up for this story. The Portuguese may have arrived in Australia in the early 16th century, and in 1605, Dutch explorer Willem Jansz reached the Australian coast and named it Cape Keer-Weer. Officially, though, it was Captain James Cook who "discovered" the Land Down Under, and the official date is April 20, 1770, the date a crewman first sighted southeastern Australia.

So that's pretty standard textbook stuff, but then, during World War II, something happened on an Australian beach that changed all of that. According to Australian Geographic, an RAAF serviceman named Morry Isenberg found some coins on the beach, and we don't mean Australian dollar coins, either. He found 900-year-old coins that originated from a medieval African sultanate.

How did the Kilwa Coins get on the beach of an "undiscovered" continent? A shipwreck, perhaps? Or maybe the Aboriginal people were more worldly than we thought they were. Perhaps they had sophisticated trade networks with Mozambique, the Swahili coast, India, the Spice Islands, and China. Nah. Let's Europeansplain to them why that can't possibly be true.

An ancient tooth that told the story of a journey

Road trips are cool, but road trips with dogs are the best. Not just because they like to hang their heads out of the car window, which is endlessly hilarious, but because dogs are just fun traveling companions who are happy no matter where you take them.

So it's not really that shocking to learn that people were road-tripping with their dogs more than 7,000 years ago. We do know it was slightly more boring than modern dog/person road trips because of the absence of car windows, but still.

Anyway, according to The Guardian, archaeologists know all about one particular road trip because of a tooth. But how can you recreate an ancient road trip based on a single tooth? Well, the tooth in question, which was found roughly one mile from Stonehenge, came from a dog that wasn't native to the area. An isotope analysis of the tooth found that the dog drank water from the Vale of York, which is 250 miles away from Stonehenge. So the animal could only have arrived at the location where the tooth was found if someone had brought it there. Not only is that evidence that someone willingly made the long journey from the Vale of York to the region near Stonehenge, it also shows that people were using domesticated dogs in Great Britain during the Mesolithic era. Cool stuff.

A mosaic tile map of the holy land shed some light on the Bible

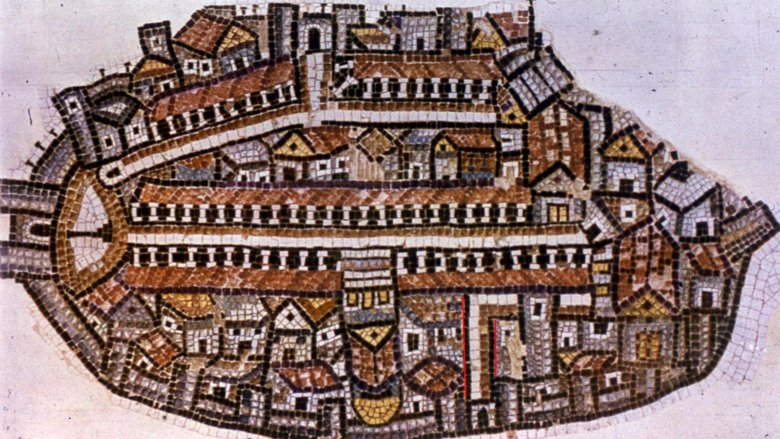

In 1894, builders in the city of Madaba, Jordan, were erecting a new church on the ruins of an old one when they uncovered an intricate mosaic floor made from some 750,000 small tiles. It was a map, dating from the 6th century AD, it covered an area about 34.5 feet by 16.5 feet, though it was much larger in antiquity and probably originally contained up to 2 million tiles. According to The Huffington Post, the map shows the biblical holy land from Lebanon to the Nile delta and from the Mediterranean to the eastern Jordanian desert. Archaeologists think the map is the oldest one depicting the region.

The Madaba Map includes place names, written in Greek, and even has details like palm trees, gates, and churches. But what was really monumental about the find is that it revealed the location of the ancient city of Zoar, which is mentioned in the Bible as a neighbor of the cities of Sodom and Gomorrah. Knowing the location of Zoar, on the southern end of the Dead Sea, provides archaeologists with a clue about where Sodom and Gomorrah might've been located.

The map still resides in its hometown of Madaba, and you can view it from behind a chain on the floor of the Church of Saint George.

An ancient treasure was a fantastic find

If you live in America, you're probably never going to find treasure buried in your backyard. The natives of our land just weren't that into treasure. But if you live in Europe, there's actually a slim chance that someone may have left a hoard of silver and gold in a field somewhere, and you might be lucky enough to find it.

According to National Geographic, in 2009, a British farmer named Fred Johnson gave a treasure-hunter named Terry Herbert permission to go metal detecting in his field. When Herbert returned, he told Johnson he'd found Anglo-Saxon treasure.

Named the Staffordshire Hoard, the find was astonishing. It contained objects made from silver, gold, and garnet, and they were nearly all objects of war, like sword-hilt fittings, pommel caps, and scabbard pendants. The treasure didn't include any coins or jewelry, and most of the objects had been bent or broken, which suggests they'd been deliberately removed from the objects they once belonged to.

There are a few theories about how this collection of precious objects might've been accumulated. Perhaps the swords of conquered soldiers had been stripped and repurposed. Unfortunately, though, there are no clues as to the identity of the treasure's original owner. All we can really say for sure is that at some point, the person who owned it all decided to bury it in a hole along an old Roman road, and that's where it stayed for 1,300 years.

The Cave of Altamira was controversial for archaeologists

In the 1800s, people were still in disagreement about the age of the world and humankind's place within it. Wait, who are we kidding? People today are still in disagreement about those things. But in those days, the discovery of something like the paintings in the Cave of Altamira was enough to create real division between scientists and everyone else.

The Cave of Altamira near Santillana del Mar in Cantabria, Spain, was discovered by a hunter in 1868. According to the Bradshaw Foundation, amateur archaeologist Marcelino Sanz de Sautuola took an interest in the cave and told everyone that he thought the paintings inside were made during the Palaeolithic era. His theories weren't exactly warmly received, though, and some people even speculated that the paintings were modern forgeries, since they were clearly too sophisticated to have been made by grunting, animal skin-clad cavemen (hooray, more humansplaining). Sautuola was publicly humiliated, but when scientists finally realized he'd been right all along, it was too late. He'd already been dead for 14 years.

The Minotaur's home changed our view of ancient literature

You probably thought that the Minotaur's labyrinth was a myth. You've heard the story, of course, where a poor bull-headed man-beast roams a massive labyrinth, eating doomed young men and unwed girls every seven years because of reasons. It's only a story, though ... except in 1894, a British archaeologist named Sir Arthur Evans went to the island of Crete in the hope of discovering the ancient city that was a feature of Greek myth and epic poetry. Three years later, he began excavating what turned out to be a spectacular palace, dating from 1600 to 1400 BC. During the excavation, Evans discovered a labyrinth-like network of rooms and passageways, which Ancient-Greece.org says may be the actual labyrinth (or at the very least its inspiration) from Greek mythology. But so far, no one has found the remains of a bull-headed man-beast.

The palace at Knossos isn't really the dark and terrifying place described in the myth, though. It's grand and elaborate, and its walls are covered in beautiful frescoes. During the 31-year excavation, Arthur Evans attempted to reconstruct the palace as he thought it might've looked in antiquity, so the remains are beautiful even though his work has been criticized as probably not especially accurate. Still, the restorations allow visitors to appreciate the scale and grandeur of the palace, which to date is still considered to be Europe's oldest city.