Military Battles That Were Worse Than You Thought

Kids play battle a lot, and for a child it seems fun. It's everything children like: loud noise, competition, mild danger, and imitation of adult activities they don't really understand. And for some people, the love of playing battle persists into adulthood, as evidenced by people who dress in costumes to reenact historical conflicts. However, real-life battles are, for the vast majority of participants, not nearly so fun. They're confusing, frightening, extremely dangerous, and if your side does especially badly, you could wind up in a history book for all the wrong reasons.

Even from this baseline, some battles are especially bad, either because of the particular circumstances of the battle itself (imagine having to fight to the death in a snowstorm or with a tummyache) or because the battle turns out to have been one of the important ones schoolchildren have to memorize; and you lost. Worse still, some battles were a race to the bottom in terms of their cruelty and brutality.

Agincourt

The Hundred Years' War didn't really run for the whole 116 years between 1337 and 1453, or else there'd have been no one left in England or France, but when the fighting was running hot, the conflict could be truly savage. In 1415, Henry V of England had invaded France again, hoping to take advantage of the mental illness of its king, Charles VI, who thought he was made of glass. Weakened by a longer-than-expected siege of Harfleur, Henry's army was headed back to England to regroup when it was caught by a French force near the village of Agincourt.

The French outnumbered the English, though sources disagree by how much, and what forces the English had were also woozy from an outbreak of dysentery. The English positioned themselves in a narrow field, planted sharp sticks to slow charges, and according to some accounts, removed their trousers so as not to be interrupted by having to lower them for ... still-having-dysentery purposes. (It is rumored but not provable that the English forces dipped their arrows in the waste to create biological weapons, and of course it's easy to imagine a cloud of feces-streaked arrows also having a certain psychological effect.)

The half-naked diarrhea archers absolutely obliterated the French forces, who were wedged between the woods that lined the battlefield and, in later waves, slowed down by piles of their own dead. The defeat and the further English advances it made possible meant that in 1420, Henry V was made heir to the French crown. The wheel of fortune kept turning, though, as Henry V died in 1422; from diarrhea.

Iwo Jima

The Battle of Iwo Jima suffers a bit from its own iconic status. Everyone remembers the famous picture of the Marines raising the Stars and Stripes over the island (and that the U.S. and its allies would soon complete their victory over Japan), but fewer people recall just how bloody the battle for the island was.

Iwo Jima is tiny at only about 8 square miles, a little more than a third of Manhattan. However, in early 1945 it was just about close enough to Tokyo to allow American bombers to attack the Japanese capital, along with many other targets in the Home Islands, and already contained three airfields. If the United States took Iwo Jima, it would truly have a dagger pointed at the Empire's throat, and the Japanese knew it. Around 70,000 Marines landed on the island in February 1945, along with naval engineers to provide support, and even this massive complement of men needed five weeks and reinforcements to evict the Japanese forces — and that's after a three-day artillery barrage intended to crack Japanese resistance.

Unfortunately for the American invaders, the Japanese defenders had honeycombed the island with tunnels and underground fortifications, and were furthermore able to make use of the craters the initial bombardment had pocked into the island's surface. Some of these overlooked the sandy beaches on which the Marines needed to land, allowing the Japanese to pelt the amphibious assault. The ensuing fighting killed nearly all of the 21,000 Japanese defenders and some 7,000 Americans.

Gate Pā

The Treaty of Waitangi was signed in 1840 between a number of Maori tribes and the British Crown, but significant differences in the English and Maori texts meant that the two parties expected very different outcomes from the signing. That led to the decades-long New Zealand Wars, when British forces opened up much of the islands for settlement in the face of sometimes ferocious Maori resistance.

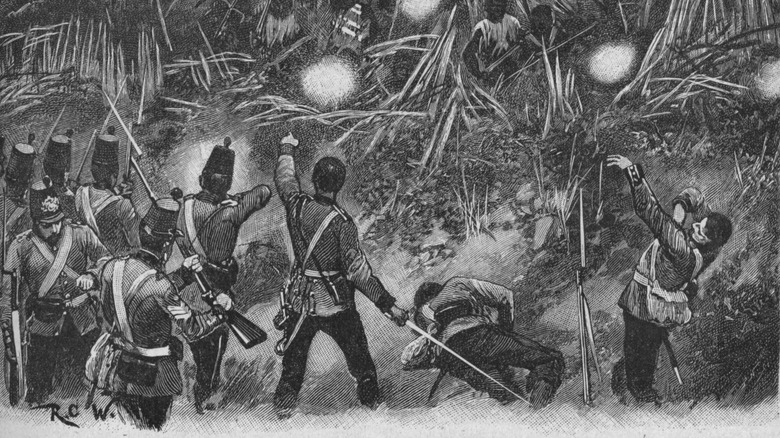

The western North Island was a center of resistance, but supplies and reinforcements were coming in from the broad, fertile Bay of Plenty in the island's north. To cut this flow, the British needed to capture Gate Pā, a "pā" being a traditional Maori fort and "gate" referring to the big gate it had. The British trained their guns on the pā and proceeded to try to blow it to smithereens, but did not realize what they were up against. The fort's designer, Pene Taka Tuaia, had seen field guns in action and built the pā to resist them, with bunkers and separate redoubts so all was not lost if one was breached.

After a horrific but clumsy bombardment of eight hours, in which the British almost shot over the pā and hit their fellows on the other side, there was no motion from within the fort. They then charged, only to find that the Maori defenders had almost all survived and were calmly waiting to repulse any attempt to storm the pā. Close-quarters fighting in the fortifications efficiently killed or injured most of the British officers, and the British invaders were forced into an embarrassing retreat, even abandoning some of their dying fellows.

Sedan

In 1870, an allied army of Prussians and Germans began rolling into France after the emperor of France and nephew of the first Napoleon, Napoleon III, had declared war against Prussia. The French were very optimistic about some new guns and their reorganized army, which proved to be insufficient against the Prussian powerhouse.

A big chunk of the French forces wound up penned up in the fortified city of Metz, and the remainder, with the emperor tagging along, tried to free them instead of falling back to defend Paris. By September 1, 1870, they were trapped in the small fortress town of Sedan, near the Belgian border. With the primary general wounded and the emperor struggling with a kidney stone so severe he was unable to urinate, disaster seemed inevitable. And it was: The entire French army surrendered, and Napoleon III handed himself over personally to the king of Prussia.

The French overthrew their captive emperor, but the Third Republic was no better able to resist the Prussians than the Second Empire had been, and a mere eighteen days later, Paris was under siege. The hungry Parisians ate the animals in the zoo in their attempts to hold out, but finally caved in early 1871. In the peace settlement, Germany gobbled up France's eastern territories in Alsace-Lorraine and had the king of Prussia declared German Emperor in the palace of Versailles, laying resentments that would help kindle World War I.

Manzikert

Some think that the Byzantine Empire started its decline with its defeat at the Battle of Manzikert in 1071. It wasn't the worst battle in its history (that was probably the 1204 fall of Constantinople) or the last (the 1453 fall of Constantinople, even if that was followed by some mopping up), but Manzikert was the point at which fate seemed to turn against the glittering Greek empire that had outlasted its Roman twin.

Nomadic Seljuk Turks — fresh on the scene from their Central Asian homeland – had been pestering Byzantine strongholds in the east near the modern border with Armenia. A new emperor, Romanos IV Diogenes, had come to the throne with hopes of refreshing the neglected Byzantine army and pushing the bothersome Turks far enough away that they would no longer be a Byzantine problem. Romanos approached the Turks near Manzikert, a little fortress, and split his army to create a pincer, except half of the army disappeared; either defected, lost, or defeated in a separate engagement. Romanos's numerical advantage was gone, and his forces would be winnowed further by defections.

Nonetheless, Romanos arranged his forces for the battle and charged. The Turks backed off calmly until the exhausted Byzantines began to retreat, then swarmed them, overruning the entire army and capturing the emperor. Romanos was treated well in captivity and allowed to ransom himself for the price of three major cities, a colossal amount of gold, and the betrothal of one of his daughters for a son of Alp Arslan, leader of the Seljuks. The other Byzantines, less thrilled with the deal, blinded and deposed Romanos when he returned to Constantinople.

The Horns of Hattin

The Crusades were always sort of a long shot. A fundamentally colonial project in an era before the gunpowder and ships that made the conquest of the Americas and much of the rest of the world possible, the Crusader States clinging to the Levantine coast of the Mediterranean coast were always going to be vulnerable to a conqueror with a well-provisioned force that could outfight the always-undermanned crusader armies.

Enter Saladin. An Egyptian who had unified much of the Muslim eastern Mediterranean under his control, by 1187 he was ready to try to pull the irritating Christian thorns from his flank. His 18,000 to 24,000-man force wasn't necessarily enormously bigger than the 16,000 crusaders, but included far more cavalry. Additionally, this army was all the Crusader States had: there was no real reserve to draw on, whereas Saladin might be able to raise from his now-vast lands.

They met in Galilee, now in northern Israel. Galilee is green and fertile by Middle East standards but no Eden, and the Christian force ran out of water on its way to try to dislodge Saladin's forces from a siege of Tiberias, on the shore of Lake Galilee. Saladin scattered the thirsty men with volleys of arrows and with smoky fires, forcing them to regroup on a small extinct volcano called the Horns of Hattin. They put up no serious threat to Saladin's forces, which followed them onto the Horns of Hattin and quickly completed their victory. With this Crusader army broken, Saladin was able to retake Jerusalem later in 1187. The Crusader States would limp on for another century, but the clock was ticking.

Third Battle of Nanjing

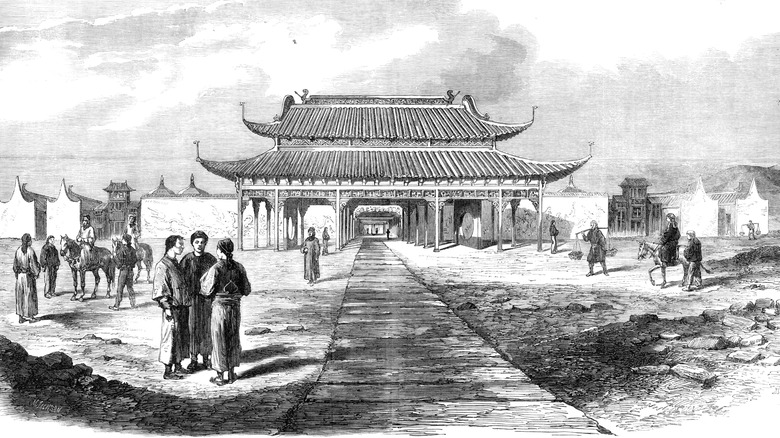

From 1850 to 1864, China was convulsed by a ferocious civil war that may have killed as many as 20 million people. The Taiping Rebellion resulted from a new religious movement founded by Hong Xiuquan, a man who claimed to be God's son and therefore Jesus's younger brother, destined to sweep evil from the land. The Taiping set their sights on overthrowing the reigning Qing dynasty of China, and by 1853 they had taken the major city of Nanjing and made it their capital.

The Taiping rebels failed to follow up their early victories with lasting statecraft, spending energy they could have used to conquer Beijing on internal squabbles, paranoia, and attempts to out-mystic one another. Internal purges (and Western help) allowed the Qing to recover, and by 1864 they were at the walls of Nanjing, hammering away with cannons and scrapping with Taiping fighters in the city's defensive earthworks. Hong refused to evacuate the city and then ate some weeds, which killed him — whether this was death by suicide or mere foolishness is unknown.

A few weeks later, the Qing army took a ridge overlooking the city and was able to pelt Nanjing to their hearts' content; shortly after that, explosives opened a 60-yard-wide breach in the walls. The Qing forces flooding into the city killed a lot of Taiping bitter-enders, but so did the Taiping themselves, choosing to set themselves ablaze rather than surrender. The death toll at Nanjing probably topped 200,000, the vast majority of them Taiping rebels.

Adwa

By the time Italy became a unified kingdom in 1861, there wasn't much left of the world to colonize, as the other European powers had already more or less divvied up everything worth having, but one big prize still lay on the board: Ethiopia. The ancient African empire, ruled by a man claiming to be the descendant of King Solomon's romance with the Queen of Sheba, lay just inland from Italian Eritrea on the coast of the Red Sea. Italy crossed into Ethiopia to pluck this plum colonial candidate, but Emperor Menelik II was ready to fight.

Part of Menelik's strategy was to seem unprepared, and he planted false intel that his army was smaller and more poorly equipped than it was. Meanwhile, the Italian army was indeed small and poorly equipped, lacking even accurate maps. General Oreste Baratieri, even after a very long march into mountainous Ethiopia, preferred to retreat, but Rome continued to hector him to attack, and quickly. So he threw his 15,000 Italians and African recruits against 100,000 Ethiopians near the city of Adwa.

The Ethiopians' stunning victory at Adwa saw some 70 percent of the Italian force killed or captured, with the remainder facing a deeply unpleasant retreat back to Eritrea. Ethiopia would stand alongside Liberia as the only independent African country until the Italians returned in 1935 and overran the country in 1936, although they were chased out again in 1941.

Waterberg

When the Herero people of German Southwest Africa (today's Namibia) began their fight against the German colonial government, their leader Samuel Maharero issued a directive that settler women and children were to be spared. The Germans were uninterested in matching this civility with an agreement of their own and sent the bloodthirsty Lothar von Trotha, a veteran of previous colonial intrigues, to beat the Herero into submission.

The Herero had pulled back to a plateau called Waterberg: according to some sources, they expected to be met by negotiators, while others argue that Waterberg was a staging point in case an evacuation into British-held Bechuanaland (now Botswana) became necessary. It became necessary, but not easy. Von Trotha encircled the Herero and trapped them on Waterberg, and on August 11, 1904, the Battle of Waterberg began with a punishing artillery barrage. The Herero were insufficiently armed, (some only had clubs, not guns), but were able to fight their way out between two German units and flee into the desert.

Von Trotha then began the genocide of the Herero. German forces pursued the Herero for a while, killing those they captured, then pulled back to wait, occupying all known water sources and constructing a gigantic fence to keep the Herero trapped in the arid Kalahari. Von Trotha issued an order announcing that any Herero found in German Southwest Africa would be shot, regardless of age, sex, or whether they were armed: two months later, this was repealed in favor of capturing surviving Herero to hold as slaves. As many as 85% of the Herero may have died, and a handful of key figures in this genocide went on to participate in the Holocaust.

Shiloh

In early 1862, there was still hope that the U.S. Civil War might end quickly. The Union was having early successes in Tennessee, and Ulysses S. Grant wanted to press his advantage to disrupt Confederate operations in northern Mississippi, with his eye on the rail nexus at Corinth. While Grant waited for reinforcements from Nashville, Confederate general Albert Johnston advanced from Corinth to prevent the Union forces from meeting and moving south.

On April 6, the Confederates were able to surprise the Union forces as they bivouacked near a little church called Shiloh. The Confederates forced the Union troops to take up the defense and cleared them from some southern areas of the battlefield, but Johnston bled to death from a lucky shot to an artery in his leg. His successor P.G.T. Beauregard, in a classic Civil War blunder, declared victory before the battle was even over, and to his enormous chagrin, the hoped-for Union reinforcements from Nashville arrived that night.

The Union army, now with a colossal 54,000 men, attacked first thing the following morning, enjoying support from boats on the Tennessee River that were able to fire cannons at the overconfident Confederates. Beauregard eventually retreated back toward Corinth: the Southern army had inflicted more casualties than it took, but the smaller force could afford to lose fewer men. All told, the combined damage to both armies was nearly 24,000 dead, wounded, or captured. Later that spring, Beauregard would abandon Corinth to Union forces, retreating to Tupelo before being reassigned to defend Charleston.

Lake Trasimene

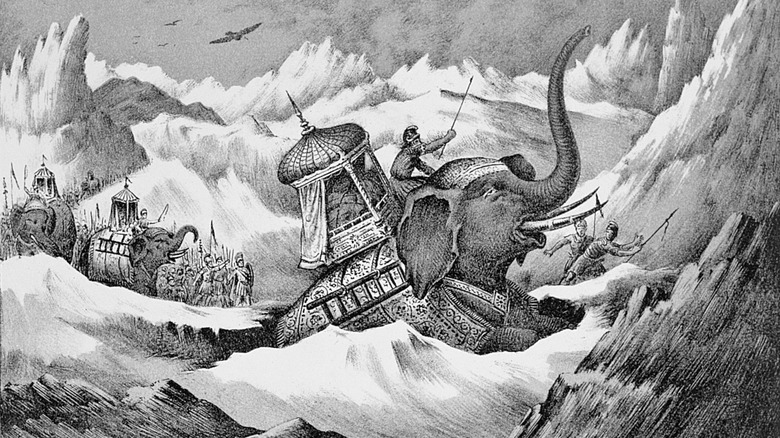

If Hannibal, the general of Rome's powerful rival Carthage, had only coaxed an army (complete with elephants) over the Alps into Italy, it would have been remembered as one of the most daring military gambits ever undertaken. But it's what he did when he came down out of the mountains that's even more impressive: in three years, Hannibal inflicted three terrible defeats on Rome, at Trebbia, Lake Trasimene, and Cannae, almost strangling the future empire in its cradle.

Cannae is the most famous of these three battles, but Lake Trasimene might have been even more miserable for the hapless Roman forces. The Romans were pleased to see that Hannibal's army had moved into hilly Tuscany, where his cavalry could not operate as well. So pleased, in fact, that they walked right into Hannibal's snare, proceeding blithely to the shore of the apparently lovely Lake Trasimene without sending scouts to see where Hannibal was. Such scouts would have said something like "hiding in the foggy hills around Lake Trasimene."

With escape and retreat blocked by the canny Hannibal, the Romans had to fight, but the contest wasn't even close. The Carthaginians pulverized the Romans, killing their commander and forcing a number of the men to retreat into the lake itself, where a number of them drowned, while others got stuck in the mud and became easy pickings. As a final insult, a body of 4,000 reinforcements sent by Rome was also captured.

Kursk

For sheer hard-to-believe numbers, no conflict beats the Western Front of World War II. The unstoppable force of the German invasion met the immovable object of the Soviet resistance, and both sides ran up their totals in every grim metric one could imagine. Among the most jaw-dropping sub-clashes was the ferocious Battle of Kursk of summer 1943, in which over 2 million fighters — that's about a Houston, Texas' worth — clashed on the plains of western Russia over a front over 100 miles long.

The Axis had failed to take Stalingrad and had been forced into a retreat, and the Soviets were pursuing them, anxious to prevent any Nazi attempt to finish what they started. The Soviet lines began to bulge outward, which the Germans incorrectly saw as an opportunity. In fact, the Soviets had made a tactical retreat, massing their forces behind landmines and other antitank weapons that bogged the Germans down, while the delighted Soviets counterattacked with the advantage in materiel that their factories had finally been able to generate.

Half a million German troops were killed, injured, or captured, and Kursk was the last serious offensive attempt Germany was able to make in the East. Kursk was as bad a reversal for the Axis on the Russian front as the Normandy landings were in the West. By November, the Soviets had recaptured Kiev, and in another 18 months, they were in Berlin.

Towton

The Wars of the Roses can be maddening to figure out: Everyone is related, everyone was winning or losing at some point, and the wars flared on and off for 30 years. Too many people wanted to be king of England, and a few of them had an actual point, so the only way to resolve the issue was decades of intermittent bloodshed from 1455 to 1485 (or 1487, if the Battle of Stoke is included).

Being a fighting peasant or lower-tier knight in the Wars of the Roses sounds appallingly unpleasant under any circumstances, but the Battle of Towton might have been the most excruciating single day of the whole bloody business. The befuddled Henry VI, supported by his ferocious wife Margaret of Anjou, faced off against the teenage upstart Duke of York. It was a miserable day in March 1461, windy and sleeting, when as many as 60,000 men gathered on a field in Yorkshire. This doesn't sound like a huge number until it's contextualized: that might have been 10 percent of all men between 16 and 60 in all of England and Wales. Given the population of the kingdom at the time, it was a massive assemblage of men ready to fight.

Both sides were instructed to take no prisoners, and so when the forces of King Henry and Margaret broke, they were slaughtered in the thousands. An estimated 28,000 people died at Towton, with the defeated royal family bolting to temporary exile in Scotland.

Teutoburg Forest

In the years leading up to 9 CE, in addition to much of the Mediterranean coastline and Gaul, Rome had conquered a little chunk of the land across the Rhine, nowhere near all of it but enough to label something "Germania" on the map and convince themselves they were entitled to the whole shebang. Varus, a seatwarmer governing Germania, let himself be hoodwinked by a false report by Arminius, leader of the Cherusci tribe, that there was a revolt brewing off in a northern, remote part of Roman Germania. Arminius accompanied Varus part of the way, then turned on him.

Details aren't totally clear, as with all ancient events, but it seems Arminius's trap was excellent, with Romans trudging through the muddy Teutoburg Forest beset by javelins and fire arrows. Over four days of fighting, the Romans fell into more and more ambushes, with many eventually choosing death on their own swords rather than capture. (Those who were captured may have been sacrificed.) As many as 20,000 Romans may have died, taking with them only a trivial number of Germans.

When Augustus Caesar got the news, the emperor reportedly went almost entirely off the rails, abandoning grooming and screaming, "Give me back my legions!" Subsequent punitive expeditions failed, and most of Germany remained un-Roman for the rest of the life of the empire.

Siege of Kaffa

The city of Feodosia in the oft-contested Crimea spent one chapter of its long and eventful existence as a Genoese trading colony, established in 1266 by agreement with the ruling Mongol state, and then known as Kaffa. The relationship was not particularly easy and the city was disestablished and reestablished, but it was rich and bustling in the 1340s, when war broke out between the Genoese and the Mongol-Turkic hybrid Golden Horde. An initial siege was broken by Italian reinforcements, and then a second attempt to take the city faltered in 1346, when the Golden Horde soldiers and their Venetian allies started falling over dead from the Black Death.

If you have a particularly ghoulish frame of mind, as apparently someone in the Mongol camp did, you could see the presence of diseased corpses as an opportunity. Reportedly, they loaded their dead comrades into the catapults and yeeted the remains over the walls of Kaffa, pummeling the besieged city with an especially gruesome biological weapon. The plague took root in the horrified city, but with the Golden Horde breaking off the siege to find somewhere quiet to die, the people of Kaffa who wished to bolt could and did.

That gruesome event is also how the Black Death entered Europe. The fleeing Genoese of Kaffa carried it back to one of the richest and most populous cities in Italy, from which it ripped across Europe in the following years. For the inhabitants of Kaffa, one small comfort may have been that the Golden Horde gave up on taking the city, and it stayed in the hands of those Genoese who survived until 1475.

Leipzig

By 1813, the once-invincible Napoleon was finally on the defensive. With his fabled invasion of Russia already identified as a debacle for the ages and his occupation of Spain and Portugal hemorrhaging resources, Napoleon needed to think of something to thwart the vengeance-minded Russia-Prussia alliance rolling through Central Europe. Naturally, Napoleon raised a new army and invaded Germany again. Napoleon himself did well enough, but other French generals weren't so successful, and so he abandoned his plan to seize Berlin in favor of standing and fighting at Leipzig.

Leipzig was and still is conveniently (or dangerously, depending on the decade) situated on a plain at the juncture of several rivers and roads. Outside the city, the tsar of Russia, emperor of Austria, and king of Prussia met personally to plan. On October 16, the allied armies began grinding through the suburbs of Leipzig in the face of fierce resistance and powerful artillery. The first day of fighting was so bloody that everyone stopped the following day to gather the dead; unfortunately for Napoleon, allied reinforcements arrived that day, including some under his old subordinate Jean-Baptiste-Jules Bernadotte, now the crown prince of Sweden. Bernadotte's presence inspired some of his old troops to defect from the French army.

Napoleon's late-night retreat out of Leipzig became a bloody farce. There was one bridge, which he ordered blown up after the French army had crossed it to cut off pursuit; a chain of mistakes led to its being blasted while it was very much still covered in Frenchmen. One of Napoleon's generals drowned trying to swim out of the city, and 30,000 French soldiers were captured.

Salamis

In 480 B.C., the smart money was on Persia to overrun Greece. Greek defenders had made a noble stand at Thermopylae, but nobility does not win wars; heavily armed men do, and Persia simply had many more of them than Greece did. Many of these men were also on boats, which meant that Persia could menace anywhere in Greece. So when the Persian fleet sailed to confront the smaller Greek navy in the cramped little harbor at Salamis, it seemed like this was going to be what they call "it" for Greece. Persia's King Xerxes even had his throne placed on a promontory with a view of the action for gloating purposes.

A fake retreat drew the large but unwieldy Persian ships deep into the harbor, and the Greeks then turned and pounced. The smaller Greek ships could maneuver better in the tight quarters and strike the Persians with their bronze rams. The Persian navy quickly crumbled, with the allied Queen Artemisia of Caria only escaping by crunching her ram through an allied ship that was in her way.

Xerxes lost 200 ships out of an estimated 800, and his army and navy would each be obliterated the next year. The Greeks had outfoxed the mighty Persians and could return to their favorite pastime: arguing with one another.