The Dumbest Ways To Die Throughout History

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Most people spend too much of their lives worrying about death. They hope it will happen far in the future, without pain, after a rewarding life. Failing that, some hope to go out meaningfully, laying it all down for a cause or those they love. Only a rare few realize what they should really fear is that the end will come not in a blaze of glory or with the comfort of rest, but with a whoopee-cushion blare and a round of guffaws.

Some unfortunates are remembered not for the content of their lives, but the circumstances of those lives' ends. Some people, through carelessness, recklessness, or the Fates' favorite phrase, "It couldn't happen to me!" manage to meet their (presumably frustrated) maker having done something so dumb it carried them right through to the next world. Consider these stories a warning: Death comes for us all, but sometimes it's wearing clown shoes.

Bothering people who wish to be left alone

If you've never heard of North Sentinel Island, you've got the Sentinelese people to thank for it. One of the few uncontacted tribal people left in the world, the Sentinelese would like to keep it that way, violently rejecting any and all outside efforts to initiate interaction. The government of India both respects and enforces their decision, but that hasn't kept people who think they know better from occasionally trying to badger the Sentinelese.

One of these howdy-neighbor doofuses was John Chau, a self-appointed American missionary who reasoned — correctly, technically — that the Sentinelese had never heard about Christianity. Chau decided that some American in his 20s was the right person to rectify this issue, and traveled to the island chain in which North Sentinel lies. His initial attempts to break the ice with the Sentinelese ended in the Sentinelese shooting arrows at him and taking away the small kayak he had used to land, forcing Chau to swim back to the larger fishing boat whose crew he had paid to swing him by. He asked the fishermen to take him back the following day, and they later saw his remains being buried on the beach of North Sentinel Island.

Chau had received vaccinations to prevent potentially infecting the Sentinelese with new-to-them diseases, but any contact with outsiders risks a devastating epidemic like those that tore through the indigenous populations of the Americas after European contact. Neither Chau's fate nor his potential harm to the Sentinelese has dissuaded everyone: another American busybody was arrested after trying to make contact in March 2025.

Poison makeup

The famously stark-white face of Queen Elizabeth, still visible in her portraits, was supposedly possible thanks to a thick and popular cosmetic called ceruse. It was the full-coverage foundation of its day, covering blemishes and evening out the skin tone for a striking pallor. Unfortunately, the white pigment was a lead compound, and as lead is very, very poisonous, the women (and some men) who used it often found themselves losing hair, covering blotchier skin, and even losing dental enamel.

At least one prominent death is based on ceruse, that of an 18th-century actress who married her way into a title. The Countess of Coventry's death was formally credited to tuberculosis, but a number of her contemporaries seemed convinced that the white paste she dolled up with was the real culprit. Since lead poisoning can suppress the immune system, both explanations could be partly true. Currently, a women-led research initiative called Toxic Allure is running samples on ethically sourced pigskin to test just how likely it was that dangerous amounts of lead passed into the bodies of the Countess of Coventry and her contemporaries.

It's not just surface beauty treatments that are dangerous. The all-powerful mistress of Henry II of France, Diane de Poitiers, was so invested in maintaining the youthful appearance that had ensnared the (scandalously younger) king that she drank gold-containing tonic to stop the aging process. It worked, after a fashion: Diane died, probably of glamorous but foolish gold poisoning, but reportedly kept her beauty until her death.

Drinking something you found in the bathroom

Foul-mouthed, sexy, and wild, American actress Olive Thomas was very much one of the stars who gave the '20s its image, even if she didn't make it through the decade. In 1920, Thomas was in France with her husband, actor Jack Pickford. She went into the bathroom to take something to help her sleep, and instead drank her husband's syphilis medicine. Syphilis was, at the time, treated with highly toxic and even potentially corrosive mercury compounds, and Thomas, picking up the wrong bottle in the dark and/or perhaps not understanding a label in French, slammed down a fatal dose. After a painful five days, her kidneys failed, and poor Olive Thomas died at 25.

Rumors then and now have been skeptical of the official story, with some pointing to a poison plot by her husband or an impulsive death by suicide after a night of heavy drinking. The French authorities, however, ruled her death an accident, and it was not the only recorded death caused by accidentally taking mercury-containing syphilis medicine.

Drinking something you found by the side of the road

Mithridates VI is so closely associated with poison that a recent biography of his has the metal title of "The Poison King." The ruler of Pontus, a kingdom on the southern coast of the Black Sea, Mithridates hoped to outcompete Rome for influence in Asia Minor. He failed, after an interesting career that saw him execute a rival king by forcing him to drink molten gold, organize a genocide of Italians living in Asia Minor, and develop a reputation for having made himself immune to poison by taking just a little bit each day so his body could adapt.

Mithridates used this interesting knowledge of poison against a touchingly trusting Roman invasion force. Allies of Mithridates gathered a substance called "mad honey" and left it by the side of the road for the Romans to find. A detachment of Romans indeed found it, and then, as no one had thought to warn them against eating conveniently placed honey during an invasion of a country ruled by a poison-fixated king, they ate it. The honey was full of poison from local rhododendron trees the bees had gathered pollen from, and it knocked the Romans flat. As the Roman force struggled with the symptoms of exaggerated drunkenness, gastrointestinal upset, and unsteadiness, their enemies swooped down and killed them.

Drinking the wrong alcohol

Moonshine, bootlegging, and home distilling have a bit of a cool, anti-authoritarian aura left over from Prohibition, but for some, trying to get around the government's ban on alcohol was dangerous or even fatal. This has to do with the chemical similarity between ethanol, the normal alcohol that can be fun in measured doses, and methanol, which has similar intoxicating properties but is also fatal at a much, much lower dose than ethanol. Even sublethal doses can cause blindness.

Methanol can be produced during regular fermentation or distillation, but most home distillers today understand how to manage the risks and can ensure that no dangerous levels of methanol are present. A greater danger is that methanol is often added to industrial ethanol to make it unfit for human consumption, in the belief that if something is labeled "poison" people won't drink it. Sometimes this is true, but sometimes it means people will attempt to extract the methanol so they can drink or sell the ethanol, and this was especially true during Prohibition. If the methanol extraction was done incorrectly (or not at all), the result was a potentially fatal cocktail, and bad batches of bootleg hooch regularly clogged emergency rooms during Prohibition.

Interestingly, an effective treatment for methanol poisoning is ethanol. Since it's not strictly the methanol that's toxic but its breakdown products, "diluting" the body's dose of methanol with ethanol, which is broken down by the same pathways, can slow the release of harmful byproducts to a level the body can manage.

Jumping at a window

In July 1993, a Toronto lawyer named Garry Hoy died tempting fate on the 24th story of a downtown skyscraper. The windows of this particular office building were well reinforced, and this apparently delighted Hoy. Hoy had developed a habit of throwing his entire Canadian adult male body against the windows and bouncing off unharmed — what emotional need this fulfilled can only be guessed at. One day, while squiring a group of law students around the office, Hoy did his trick again.

If all fairness, the window didn't break. Unfortunately for Hoy and any nearby pedestrians who had just eaten, the window did pop out of the frame, allowing the startled attorney to jettison himself. Hoy took his employer with him into the great beyond: he was apparently a key employee of his law firm, which had just completed a merger, and the combined stresses of his death and the merger led to a staff exodus and closure for good in 1996. The lesson here, if we need one, is to remember that safety codes are established based on normal expected use, and it's not an architect's job to protect you from your own most chaotic impulses.

Eating more poisonous fish livers than recommended

For the adventurous eater, a common bucket-list dish is fugu. This Japanese specialty sees the flesh of pufferfish sliced thin and arranged in a floral pattern on the plate, and its main excitement comes from the fact that some species of pufferfish are extremely toxic. Alternatively known as poison blowfish, they contain a poison called tetrodotoxin, a toxin that in infinitesimal doses causes tingling in the mouth, and at small doses causes death from nerves ceasing to carry signals. For this reason, Japan outlaws the serving of pufferfish flesh by those without a special license to serve this hazardous delicacy.

The liver is said to be one of the tastiest parts of the pufferfish, but unfortunately for daredevil gourmands, it can also host one of the highest concentrations of poison. This didn't slow a famous Kabuki actor named Mitsugoro Bando VIII, a performer whose artistry was so celebrated that he'd been named a national treasure by the government. To the dismay of Japanese theater lovers, one day in 1975, Bando had a hankering for fugu liver and ordered it at a tiny Kyoto restaurant. One serving was illegal; Bando bullied his way into getting four portions. It was to be his last meal, and he died a martyr to flavor later that evening.

Optimism about handling radioactive material

An important concept in nuclear physics (including the production of nuclear weapons and/or energy) is criticality. In short, criticality is when there's enough radioactivity in a substance that it can set off chain reactions, resulting in a continuous stream of high-energy radiation. Supercriticality is the next step, which can send out quick, intense bursts of radiation. When dealing with very radioactive substances, researchers have to be careful not to concentrate too much in one place to avoid reaching this threshold. This may not sound intuitive to non-scientists — a two-pound block of a substance being significantly more dangerous than two one-pound blocks — but this is something physicists study and should therefore be taken seriously.

In 1945, 23-year-old physicist Harry Daghlian was working late and alone, which was against the rules. As he built an experimental array of plutonium and tungsten carbide, an automated alarm warned him that supercriticality was dangerously close. Apparently startled or just clumsy, poor Daghlian dropped the tungsten carbide brick he was holding right on top of the assembly he'd been building, blasting himself with a fatal dose of radiation. He died about three weeks later.

The following year, Louis Slotin was using the same plutonium source to perform a different experiment. Slotin's optimistic setup involved keeping two radioactive components apart with a screwdriver end to avoid their coming fully into contact and reaching supercriticality. The screwdriver slipped, Slotin was irradiated and died nine days later, and the plutonium source gained the unfair nickname of "the demon core."

Getting too excited about a fetus's sex

Since 1958, pediatricians and expectant parents alike have enjoyed the benefits of abdominal ultrasound, which allows technicians to capture images of a fetus as it develops in the womb. This technology enables medical practitioners to check that the baby is developing normally, but it also often allows parents to know the child's sex before birth, should they wish. If nothing else, if you know the sex beforehand, you just need to choose one name, and you're ready to roll as soon as Junior or Juniorette pops out. Unfortunately for eager parents-to-be and the occasional passerby, excitement over a sneak peek at a baby's diaper area and the subsequent societal expectations that will be placed on them has started to rack up a body count.

Trendy "gender reveal" events, in which something dramatically turns pink or blue to indicate a girl or a boy, have occasionally involved more enthusiasm than safety protocols. Explosives are the main culprits, with homemade boom-boom-pow effects going off unexpectedly, with too much force, or in a cloud of hazardous debris. One 2020 gender reveal event in California touched off a massive wildfire that claimed the life of a firefighter.

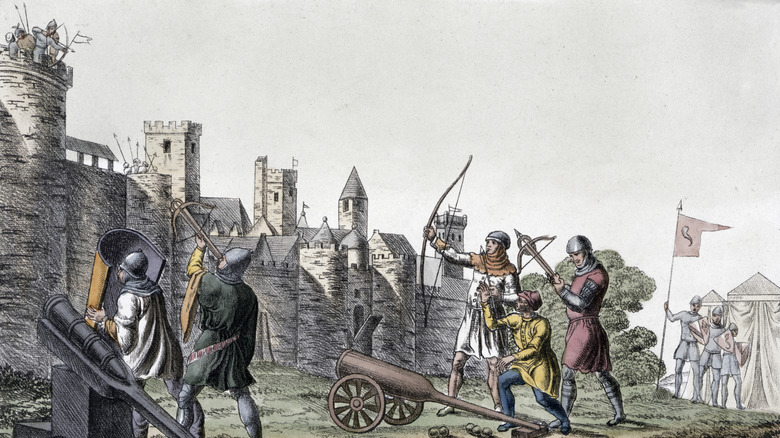

Standing out in a field when you're leading a siege

Richard the Lionhearted had an exciting life, if you like running around fighting. He revolted against his father, went on a not-very-successful crusade, was captured and held prisoner in Austria, and fought long and complex wars with the King of France over the exact extent of Richard's enormous French territories. So it might surprise you that Richard met his death not at the end of a Muslim sword or a French battleaxe, nor in a damp Viennese prison, but as a result of standing in a field looking around.

As a result of the constant power struggles in France, the Viscount of Limoges had swapped his allegiance from Richard to his rival, the king of France. Richard tore through the viscount's lands and laid siege to the castle at Châlus-Chabrol. This was not a terribly important castle, but that doesn't excuse Richard walking around the battlefield surrounding it without his armor.

A defender fired at the enemy king and hit him in the shoulder. The wound became infected, as was often the case before modern medicine, and Richard died within two weeks. He survived long enough to say goodbye to his mother, Eleanor of Aquitaine, write a will, and forgive the bowman who'd gotten him. Unfortunately for the archer, Richard's men didn't feel as generous, and when the castle later fell, he was flayed.

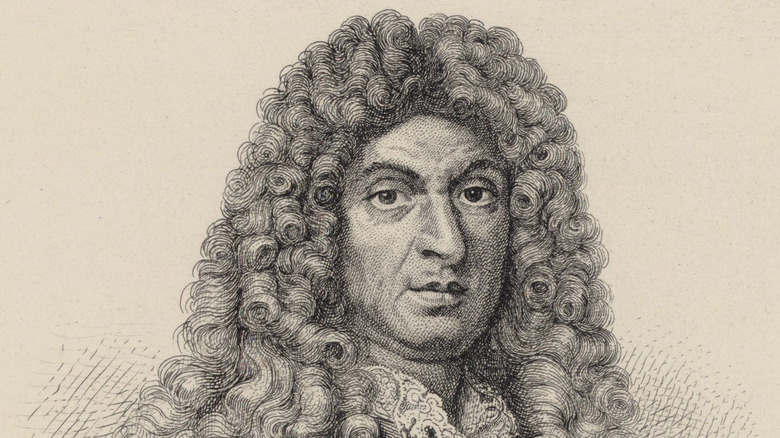

Conducting music with too much vim

Jean-Baptiste Lully was a profoundly talented musician and dancer as well as a generationally talented self-promoter. Italian by birth, by the age of 30 he was a royally appointed composer for the court of Louis XVI of France and the royal family's music teacher. From 1673 to 1687, he composed an opera every year. His authority over French music was so great that from 1674 until his death in 1687, his approval was required for any opera to be staged anywhere in France, and he's credited with helping adapt the operatic form to the French language.

In Lully's day, conductors guided their ensembles not by waving small sticks in the air but by banging big sticks on the ground in a sort of caveman-metronome act. One fateful day, Lully was conducting a hymn of thanksgiving for the king's recent recovery from an illness when he missed the ground completely, instead badly injuring his own foot. When the wound began to go septic, doctors recommended amputation to prevent further spread of the infection.

Lully announced grandly that he would prefer to die than to lose the ability to dance, and the Fates apparently heard him. He died two months later of the advancing gangrene. The modern and much lighter conducting baton was widely adopted around 1820, hopefully meaning Lully is the last conductor the music world will lose to on-the-job hazards.

Holding a snake wrong and touching its private parts

The boomslang got its cool-sounding name in the most prosaic way possible: that's just how you say "tree snake" in the Afrikaans language of South Africa. The boomslang does in fact prefer to hang out in trees and be left alone by human beings, despite rumors that it will drop or swing out of a tree to bite people, which is great for us because it's extremely venomous. Even a scratch from a fang can require medical attention, though the venom's relatively slow action and the presence of an antivenin mean bites can be effectively treated.

Unless, of course, you're in the United States in 1957, and you've just been called to confirm that a new snake at the zoo is a boomslang. When Karl Schmidt arrived at the zoo, the little snake was visibly angry, so to get a closer look, Schmidt picked it up. He didn't have a good grip, with his hand too low on the snake's "neck" instead of right behind the head. Schmidt then looked at the snake's privates to see if that could help him identify it, and the snake, well within its rights, bit him.

It was indeed a boomslang, as Schmidt would soon realize. The venom wreaked havoc on his blood, with Schmidt, ever the scientist, recording his symptoms as they appeared as long as he was able. Sadly but unsurprisingly, the ever-curious snake-poker died the following day.

Thinking the bears are your friends

Not all animals are cut out for interspecies friendship, and some do better with a secret admirer relationship. Bears are a great example of this latter category of animal. Bears are large, strong, and have both fangs and claws, so unless you're a trained wildlife agent, veterinarian, or another bear, the safest distance from a bear is generally watching it eat a salmon on TV.

Timothy Treadwell's fatal error was thinking his love for bears would be reciprocated; his girlfriend Amie Huguenard's mistake was going into the woods with Treadwell. Treadwell spent time in Katmai National Park in Alaska "among" the bears each summer, filming and interacting with them. In October 2003, Treadwell and Huguenard were camping near a salmon run (a prime feeding spot for bears) when an older male attacked and partly consumed them. Six minutes of audio were captured on one of Treadwell's recording devices, leaving no doubt as to what happened.

Treadwell loved bears so much that on one of his recordings, he's heard telling a bear he named Quincy to eat him if he was hungry enough (Quincy was not, apparently, the bear that did just that). Treadwell's own recklessness contributed to the deaths of both his girlfriend and the bear that killed them, which was killed by rangers shortly after its attack on the couple.

Stabbing the wrong elephant

In 167 B.C., Antiochus IV, king of Seleucid Syria, did the one thing you should never do if you suspect you may be in a bible story: he invaded Jerusalem and defiled the temple, attempting to reconsecrate it to Zeus. This gave rise to a furious, idol-smashing rebellion among Syria's Jewish subjects, and the resulting Maccabean Revolt had a number of complicated results. The rebel Jews were able to secure their right to freedom of worship, but their appeal to Rome for aid landed them on the emerging empire's radar. The post-Antiochus reconsecration of the temple is commemorated annually at Hannukah, the holiday of eight lights.

According to the biblical book of Maccabees, one of the Jews' attempts to dislodge Seleucid forces from Judea saw an act of stunning, completely misplaced bravery. The Seleucids had elephant cavalry, and so when one of the elephants involved was noticeably larger and grander than the others, their enemies assumed the Seleucid king was riding it. A Jewish warrior named Eleazar Avaran bolted for the elephant, fought his way underneath it, and stabbed it. The dying animal fell on Eleazar and crushed him. Alas, the Seleucid king, who was apparently elsewhere, continued to advance on Jerusalem.

Trying to show how someone could have accidentally shot himself

Clement Vallandigham would have been an interesting enough historical footnote even if he hadn't died in odd circumstances. A member of the House of Representatives for a Dayton-area seat and an advocate of enslavement and states' rights, Vallandigham didn't let his Ohio roots interfere with his sympathy for the Confederacy. Vallandigham was arrested for protesting the Civil War and banished to the Confederacy, but bolted that sinking ship for Canada and then snuck right back into Ohio to attempt to regain his congressional seat.

Vallandigham did not win that election and returned to law practice, instead winning most of his cases. In June 1871, Vallandigham was defending a man accused of shooting another in a bar fight, but he believed his client's protestation that the victim had in fact accidentally shot himself. After a few experiments shooting fabric from various distances, Vallandigham brought a pistol to court to demonstrate how the victim might have shot himself. In the act of showing how a man drawing a gun as he rose from the floor might accidentally fire it, Vallandigham — you guessed it — accidentally fired the gun he was drawing, shooting himself. He died the following morning. Vallandigham's client was acquitted on his third trial, only to apparently be murdered himself four years later.

Excessively dramatic gestures

Before her untimely death in 1927, Isadora Duncan changed dance forever. Inspired by both the ideals and the aesthetics of classical Greece, Duncan's loose costumes and bare feet shocked some observers, yet inspired her fellow artists and brought her success on European and, eventually, American stages. By 50, she had lived through World War I, the deaths of her two children in an accident, and pushback against her fascination with revolutionary Russia, so it's hard to blame her for flirting with a young man and asking to go for a ride in his Bugatti. She'd earned some fun.

Unfortunately, the ever-dramatic Duncan wanted to make an exit. She turned to say "Goodbye my friends, I go to glory!," which is a great exit line but a little over the top for a mere spin in a sports car. Her flowing scarf caught the rear axle of the car, pulled taught, and broke the dancer's neck.

Duncan might be interested to know that sudden injury from neckware caught in a wheel is now referred to by some as "Isadora Duncan syndrome." She would, hopefully, be pleased that modern medicine has managed to keep at least one other victim from following her: an attendee of the Edinburgh Fringe Festival caught her scarf in a pedicab wheel and, though she was seriously injured, recovered.

Carelessness around fire

One of the best examples of what can happen when people are insufficiently careful around fire comes from the Middle Ages, from a party imaginatively remembered as the Ball of the Burning Men.

King Charles VI of France, who suffered from mental illness and was not terribly sensible at his best, and his wife Queen Isabeau had thrown a wedding celebration for two members of their household. For an added thrill, the king and five of his friends dressed in costumes meant to represent wild men, and these costumes were made in part of wax-soaked linen. When one of them came too near one of the torches that lit interior spaces in the pre-light-bulb era, the inevitable happened. The flame leapt from wild man to wild man, and the king was only saved when a prudent duchess threw her skirts over him.

These toasted noblemen were joined in fiery infamy in 1857, when a rebellious Habsburg archduchess, Mathilda, almost got caught smoking a cigarette by her father. In her attempt to hide her smoke behind her, she ignited her dress. Not only did she die, but her father also realized she had been smoking. Stanislaw Leszczynski, ex-king of Poland and duke of Lorraine, also deserves a place in this smoky fraternity: as he tried to light his pipe in the fireplace, his pajamas caught fire.

Overeagerness to test a parachute

Good enough is usually good enough, as indifferent students and middling employees have been saying for years. But every once in a while, you have to be absolutely sure that what you're doing is actually, completely, all the way for-real good, complete, perfect, and excellent, especially when you're trying to invent a parachute.

In common with most inventors killed by their own inventions, Franz Reichelt meant well. In the early 1910s, aviation was just getting off the ground, and Reichelt wanted to invent something that would allow pilots to safely bail out if their flight ran into trouble. After yeeting dummies equipped with foldable silk wings out of his fifth-story window, Reichelt moved onto the next obvious phase of testing: He made himself a parachute-like apparatus and told the press he was going to demonstrate it at the Eiffel Tower.

When it became clear that he would not be testing the parachute with a dummy but with his own singular and precious body, people tried to dissuade him, but eventually the police allowed Reichelt to ascend to the observation deck. The brave Parisian jumped — and plummeted, followed to the ground by an ineffective wad of fabric.

Lollygagging

There's a serious difference between a road trip and an escape, and unfortunately for the French crown, Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette failed to appreciate it. In June 1791, the French Revolution was getting a tad hot, and so the royal family decided a managed retreat might be the best option. They would slip out of Paris and skedaddle to or near the Austrian Netherlands, governed by Marie-Antoinette's sister, and figure out their next steps away from Parisian pressure (Austrian military support optional).

There was one ultimately fatal flaw: Their carriage was yellow. Faced with a potentially life-or-death escapade, the king and queen chose a large and vivid vehicle, full of heavy things they thought they might need, which they rode at a convenient pace. Louis kept the window shades down, apparently thinking people would like to see the distinctive royal schnozola and jowls they might recognize from the money.

Even with all this dawdling and indiscretion, they almost made it. A mere 40 miles from the border fortress that was their destination, the royal entourage was intercepted and sent back to Paris, where most of the would-be escapees died. Three — Marie Antoinette, Louis XVI, and the king's sister Madame Elisabeth — were guillotined.

Fighting on horseback while blind

John the Blind, a prince of Luxembourg who grew up in France, became king of Bohemia in the musical-thrones game of medieval dynasties. Unfortunately for most of the people involved, John didn't like his Czech wife or his Czech subjects, so he distracted himself by trying to become king of Poland and invading nearby territories. The hard-fighting prince developed an eye condition in his late 30s and lost his sight, but that didn't stop him from lending his support to the king of France when the Hundred Years War began in 1337.

Unwilling to simply send men, John inexplicably went to France to fight himself, and discovered that medieval horseback combat is extremely difficult when visually impaired. John was one of four kings fighting on the French side at the battle of Crecy in 1346, but the only one whose horse had to be tied to those of his neighbors for safety. The Bohemian king and his escort rode into battle but not out of it, as Crecy was a crushing English victory that claimed John's life, among many others.