Why You'd Never Survive As A Soldier During WWII

There's plenty that your high school history class didn't teach you about World War II. There are the nightmarish World War II battle stories most people haven't heard, which were probably not appropriate for school children anyway, and the many strange rules soldiers followed during World War II. But if there is one overwhelming point that probably wasn't emphasized, it was this: Had you been fighting in World War II, there is a very good chance you would not have survived.

Sure, we all like to imagine that we would not only have been one of the good guys during the war, but would have been extra brave and come home a hero. While plenty of the people who fought and died in the war did do very heroic things, the point is, they still died. Then there are the ones who died in accidents, or due to disease, or the weather, or even animal attacks. There were plenty of ways to die during the biggest international conflict in history, and those who came home were lucky to survive them all.

So, regardless of how well trained or mentally prepared you think you'd have been for the fight, here's why you'd probably never have survived as a soldier during World War II.

Millions were killed in action

If you judge how tragic and terrible a war was by the number of people who died fighting in it, then no war comes close to World War II. It was a wholesale slaughter of millions of combatants. While, as we shall see, there were seemingly infinite numbers of ways a soldier could die while fighting in the war, there was one way they were likely to die above all others: Battlefield deaths killed more troops during World War II than in any other conflict in history.

The deadliest battles of World War II saw hundreds of thousands of soldiers die. To be clear, these were not one-day battles; in some cases, they stretched on for months. But the carnage was almost unbelievable. Overall, it is estimated that 15 million combatants died during the war. For American troops, the deadliest engagement was the weeks-long Battle of the Bulge. It is estimated that 19,000 U.S. soldiers died on the battlefield, not including the tens of thousands more who were injured or missing in action and later died away from the fighting.

Some troops died in battle in ways they might never have expected when they signed up to fight. For the Allied soldiers in the Pacific, as the war got increasingly worse for Japan, there was a massive increase in the number of kamikaze attacks. The USS Laffey was struck by at least six Japanese suicide bombers in one day, and the attacks and resulting fires killed 32 sailors.

You could die horribly from your wounds

If you found yourself fighting in World War II and were one of the lucky ones who survived your time on the battlefield, that didn't mean you were out of the woods. Even if you were alive at the end of a long day's fighting, there was still a good chance you would have been wounded. And with battlefield medicine not being the same quality as in a nice sterile hospital, like you would probably be used to at home, dying as a result of your wound was a real danger.

It's hard to fathom what it was really like as a medic in World War II. According to numbers from the U.S. Army, in all theaters of World War II combined, their branch of the military saw 592,623 soldiers wounded in action. Of these, 26,762 died of their wounds. That means that nearly 5% of U.S. troops who were wounded died of their injuries.

Your chances of surviving depended on where on your body you were wounded and what had caused the injury. The biggest predictor of whether you would survive was how quickly you got medical attention. If you received proper medical care within an hour, you had a solid 90% chance of survival; by the time eight hours had passed, your chances dropped to 25%. Your survival rate also varied depending on the theater of war you were fighting in. In general, troops injured in Europe had a better chance of survival than in the Pacific.

Soldiers had to contend with the elements

World War II was, as the name clearly states, a global conflict. This meant that combatants faced very different conditions depending on where on Earth they were sent to fight. Troops could find themselves anywhere from the frozen steppes of the Soviet Union to the dry deserts of North Africa to the humid jungles of Pacific islands. Each of these harsh terrains involved its own difficulties when it came to the weather, many of which could kill you.

In Europe, the main element-based problems facing soldiers were being cold and wet. Trenches were used in World War II, and if there was heavy rain, this could mean soldiers were forced to stand in feet of water for days or weeks at a time. This resulted in a horrible condition called trench foot, which sometimes led to gangrene and death. In the winter, snow replaced rain, and the problem of trench foot was replaced by frostbite, although the worst results were the same for the soldiers.

In the Pacific theater, as well as the Middle East and North Africa, it was the excessive heat that killed soldiers. This was such a problem that militaries found it necessary to change the time of day that hard labor was performed, lest too many troops get injured or die from heat stroke. There were periods of the day when almost any exertion whatsoever was dangerous, something most U.S. troops from more temperate climes would never have experienced before.

There were military accidents on the front lines and home front

Not every enlisted person who died while on military duty was on the front lines at the time. Some of them had not even left their home country yet. For American troops, the home front was never in any real danger of coming under widespread attack, so if you were still in basic training or assigned to duty in the United States, it probably seemed like you were safe for the time being. But sadly, accidents can happen in any line of work, and World War II saw some truly horrible tragedies occur on U.S. soil that had nothing to do with the Axis powers we were fighting.

The most dangerous job you could have in the military was that of a pilot or flight crew member. While you might go into flight school knowing that being shot down by an ace fighter above a battlefield was a possibility, what you were probably less prepared for was the fact that a shocking number of World War II pilots and crewmen died in flying accidents.

Even working in a shipyard could be extremely dangerous. Soldiers and sailors would be tasked with loading and unloading explosives and munitions onto ships. An errant flame or missed safety step meant unimaginable carnage. On July 17, 1944, an accident resulted in California's catastrophic Port Chicago disaster. A massive explosion — later determined to be caused by unsafe working conditions — destroyed multiple ships, spread debris over a mile away, and killed 320 sailors instantly.

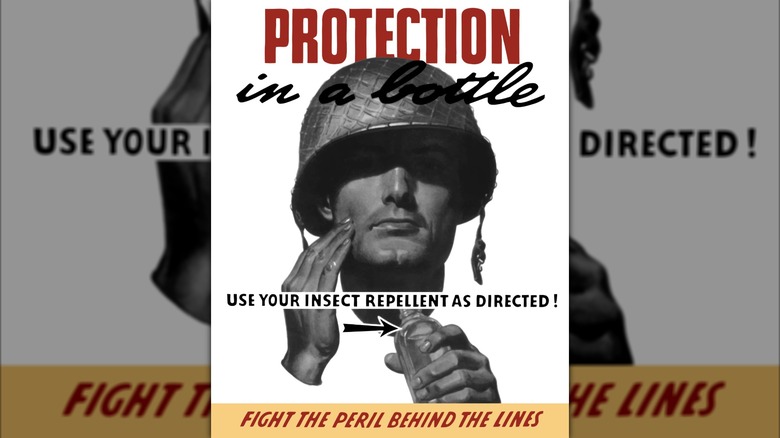

Your weapon could malfunction

The fog of war can lead to hasty or ill-informed decisions. As a soldier, you can only hope that the people in charge of selecting the weapons you were sent to fight with didn't cut any corners or miss any important signs. No one is perfect, however, and World War II did see soldiers sent to the front lines to fight with untested or — more unforgivably — knowingly faulty weapons, which is one of the more messed-up things that actually happened in World War II.

Perhaps the most notable instance of this was the Mark 14 torpedo. When the U.S. joined the war, this was the most advanced way the Navy had to blow enemy ships out of the water in the Pacific. But what sailors soon discovered was that they often didn't explode at all. One reported firing eight duds in a row to his superiors. He was not the first sailor to note this issue; the torpedoes had about an 80% failure rate. Yet submarines were still sent out with the duds, meaning sailors died due to known flaws with the weapons.

Even weapons that worked as they were supposed to could have random, unexpected issues. Mortar shells (pictured) were used to great success by the Allies in World War II and were considered exceptionally safe. This good record didn't make a difference to the 38 U.S. troops killed by prematurely exploding mortar shells over the course of the war, however.

POWs were routinely slaughtered

In theory, if you are a soldier in a war who is captured by the enemy, there are rules about the basic level of humane treatment you are required to receive. World War I had shown that the rules as they stood during that conflict were not good enough, and prisoners of war were badly mistreated. In 1929, after years of working on a draft, the International Red Cross presented a new treaty on POWs. The Convention Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War was signed in Geneva that year, and it went into effect in 1931. Despite this, many POWs were horrifically mistreated and killed during World War II.

The Japanese, German, and Soviet militaries all regularly mass murdered their POWs. This could be achieved in various ways. Sometimes it meant withholding or limiting vital medicine when illness raced through a camp. Other times it meant murdering POWs outright. The Japanese had been in control of the Philippines for most of the war, but as Allied troops invaded in 1944, the Japanese troops killed 139 American POWs by lighting a bunker on fire and shooting those who ran out. Some Axis POWs were murdered, including the mass shootings of Italian military prisoners in 1943.

Other times, it was not a systemic slaughtering of whole groups of POWs, but individual guards who killed them in different, terrible ways. German soldiers were known to let Soviet POWs freeze to death or starve. Others would beat their prisoners to death or shoot them for no reason.

Friendly fire was a terrifying danger

When you headed off to fight in World War II, you might not have known everything about what you were getting into, but one very basic fact every soldier should grasp is who was on their side and who they were fighting. Unfortunately, war is confusing, and mistakes are unavoidable. Sometimes this led to the unbelievable tragedy of a soldier not coming home from the war, not because of something the enemy had done, but because of the actions of those on their own side.

It happened far more than you might think. An estimated 12-14% of all U.S. military deaths during the war were caused by friendly fire, also known as fratricide or amicicide. These numbers would have surprised troops during World War II as well. The "official" number that was included in the U.S. Army Infantry School casebook that the soldiers were trained on was that just 2.2% of deaths were caused by friendly fire, a percentage that had not been arrived at in any mathematically sound way.

The stories of friendly fire incidents are terrifying: Troops scrambled as they were bombed by their own planes. Pilots watched as the planes beside them were shot down by forces on their own side, helpless to stop it. And 53 ships in the Pacific lost a total of 186 sailors to friendly fire. In fact, incidents of amicicide only increased in frequency for U.S. troops as the war went on.

Disease was rampant

Battlefield medics didn't just have to deal with the horrible wounds soldiers suffered from fighting during World War II. There was a very different type of enemy lurking everywhere, no matter what theater of the war you were sent to. That was the microscopic type of enemy, the viruses and bacteria that could enter your body in any number of ways and cause untold misery — if you were lucky. If you were unlucky, there were dozens of diseases you could die from as a soldier on the front lines.

Everything from dysentery to typhoid to cholera to malaria killed millions of soldiers during the war. In the Pacific, mosquitoes spread malaria among troops on both sides of the conflict until it was an epidemic that affected battle-readiness. This was made worse by the lack of quinine available to treat the disease. POWs were given even less treatment in camps, which meant the deaths attributed to malaria in these places numbered in the hundreds or even thousands per month.

Dysentery was also endemic among POWs, since it was almost impossible for them to maintain the cleanliness standards necessary to keep their water clean from fecal matter. Some estimated that virtually every prisoner got it at some point. This could mean going to the bathroom a dozen times a day, growing increasingly weaker. Lieutenant Colonel A.E. Coates wrote of the Allied POWs in Burma and Thailand, "A hut full of dysentery patients was known as the 'Dead House' — rarely did one admitted, come out alive" (via COFEPOW).

The mental anguish could be too much

As the famous saying goes, war is hell. It's hard for anyone who has never faced down the barrel of a gun, day after day, week after week, to understand the toll it takes on the human mind. Not only is a soldier dealing with the reality of their own possible death, but the strain of having killed others as well. No matter how sure you are that you are fighting on the right side of history, there will be times when it all becomes too much to bear.

That being said, World War II is notable for having surprisingly few tragic incidents of this kind. While suicide rates of active duty U.S. Army soldiers were the lowest ever during this war, the stress, fear, and trauma did result in some troops taking their own lives. It is estimated that about five in every 100,000 soldiers died this way from 1944-45. The fact that this was also the first conflict where the U.S. military tried measures to mitigate suicide risk may have helped keep the numbers low.

But the Allies won the war. Troops who faced a crushing defeat sometimes resorted to suicide. This was particularly true of Japanese soldiers, who encouraged (or forced) civilians to do the same. On Okinawa, one-third of the island ended their lives this way.

If you or someone you know is struggling or in crisis, help is available. Call or text 988 or chat 988lifeline.org

Even animals could be deadly

It is hard enough knowing that there are thousands of people on the other side of enemy lines who want you dead, but soldiers in World War II occasionally had to be wary of less intelligent but just as deadly foes as well. While plenty of mosquitoes and other bugs could rightly be blamed for deaths by disease, when it came to larger animals, the deaths of soldiers could be a lot more surprising, if just as tragic.

One of the more chilling war stories that'll haunt you for a long time comes from the eyewitness accounts of American troops. While some historians doubt the veracity of this story, several U.S. soldiers reported that as they pushed the enemy forces back on Ramree Island off of Burma, the Japanese soldiers entered swamps full of crocodiles, either in search of food or for cover. Regardless of the reason, the soldiers reported that the crocodiles killed most of them.

Even domesticated animals could be dangerous, although in this case, maybe some of the soldiers involved kind of got what was coming to them. The Soviets attempted to train dogs to wear what were effectively suicide vests (pictured), which would blow up enemy tanks when the dogs walked underneath them. The problem was that in the heat of battle, the frightened dogs often turned around and returned to their handlers. At least six anti-tank dogs blew up their own side's trenches this way. About 300 tanks were destroyed by the dogs as well.

Troops resorted to drinking bad booze

Actor Lee Powell, who once played the Lone Ranger, died in World War II. It was said that this was the result of drinking poisoned sake while celebrating a victory. While this is unproven, it is true that sailors drank "torpedo juice" and soldiers imbibed various types of moonshine during the war. These concoctions routinely killed them.

In the first six months of 1945, 188 American soldiers fighting in France and Germany died from drinking moonshine. But it was in the Pacific that so-called "torpedo juice," made from the ethanol surrounding torpedoes, was a real problem. Everyone was aware of the issue. When First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt toured the Pacific Theater in 1943, she noted, "Last night, four men died from drinking distilled shellac." (In reality, the "shellac" was probably torpedo juice.)

Navy hospital corpsman Norton Lund recalled, "We had guys drinking alcohol. Torpedo juice they call it. We got a couple of guys that got the wrong stuff. You can go blind from it, and you can die from it. We had that problem." Thomas Duncan, who enlisted in the Navy after Pearl Harbor, described a tragic incident involving a 22-year-old sailor who drank the homemade liquor, went to bed, and died in his sleep (via the Anchorage Daily News).

If you or anyone you know needs help with addiction issues, help is available. Visit the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website or contact SAMHSA's National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).

Millions of troops starved

Napoleon Bonaparte and Frederick the Great are both credited with the saying, "An army marches on its stomach." Regardless of whether one or neither of them actually said it, the sentiment is accurate. You cannot have a proper fighting force, regardless of how well-trained they are or how advanced their weapons are, if they are hungry. This means that hunger can be a powerful weapon to use against the enemy, although it is also more than a little ethically dubious.

The Bataan campaign was a disaster for the Allies, and thousands of soldiers starved during the fighting. Allied POWs were often starved in camps as well; the above photo shows some searching for anything edible in a burn pile.

The U.S. was not above using starvation as a weapon of war in the Pacific theater. It is estimated that up to 1.4 million Japanese soldiers died from starvation while on the front lines, at least partly due to U.S. blockades of their isolated island outposts. The Japanese troops could go months without any new supplies and were reduced to eating any source of meat, including snakes and rats. When those ran out, they attempted to subsist on grass. Perhaps not surprisingly, soldiers with lower ranks died of starvation in high numbers, and sooner, than officers. This was, of course, horrible for morale, if the malnourished soldiers even had the physical ability to fight. It also made them more susceptible to dying from disease.

Occupiers had to worry about sabotage

Here's the good news for anyone who assumes they would, of course, be on the winning side in World War II if they had been fighting in it: You probably wouldn't have had to worry about dying from an act of sabotage. This type of danger was mostly a problem for Axis troops when they were occupying countries in Europe. Unhappy with being occupied, the locals would fight back, and destroying infrastructure was a key way to disrupt Axis plans. It was also something that could be done under the cover of darkness, and sometimes in a delayed manner, which meant it was safer for those attempting it.

Not all, or even most, incidents of sabotage were meant to kill occupying forces. Generally, sabotage was effective if it just caused problems for the enemy. Slowing down the wheels of bureaucracy or cutting off power was just as important as taking out a soldier. But sometimes these actions were meant to leave casualties.

One of the deadliest uses of sabotage was by French Resistance groups, which would destroy railway lines. This could be as simple as removing bolts or as dramatic as blowing them up as trains passed. In 1942, there were two attacks in two weeks on railways in Airan, France. This resulted in train derailments that killed 38 German soldiers. The punishment for those involved was dire, with dozens of people being executed and many more arrested. Eighty were sent to Auschwitz.

Snipers were silent and deadly

While being shot and killed in war ends in the same result no matter who did it, there is something extra terrifying about the idea of being killed by a sniper. World War II saw most militaries employ snipers. This was a surprise to some; while snipers had been used during the First World War, in 1942, sniping instructor Lt. Col. N.A.D. Armstrong explained, "There appeared to be a tendency amongst Army musketry men to scorn the sniper — they held that sniping was only a 'phenomenon' of trench warfare and would be unlikely to occur again" (via Warfare History Network).

World War II snipers were exceptionally deadly, particularly those from the Soviet Union. Historians consider the hard-won victory at the Battle of Stalingrad partially thanks to how good the Soviet snipers were. While most of their snipers were men, they also allowed women to join up. Lyudmila Pavlichenko, a.k.a. "Lady Death," was probably the most successful female sniper in history; she had 309 credited kills before being injured and pulled from the front lines for the rest of the war. She was already a war hero due to her exploits, and it was considered too dangerous to send her back, in case her death hurt troop morale.

The Finnish sniper Simo Häyhä, a.k.a. "White Death," fought the Soviets from 1939-1940 during what was known as the Winter War. He estimated that in a matter of months, he got over 500 kills.

Chemical weapons were in limited battlefield use

World War I saw the use of chemical weapons, such as poison gas, deployed on the battlefield. This led to the deaths of thousands of soldiers and more horrific injuries suffered by those who lived, including blindness. The carnage from these weapons was so horrific that both Franklin D. Roosevelt and Adolf Hitler were against using them as part of the fighting in World War II.

There is, of course, no question that chemical weapons including Zyklon B were used by the Nazis to kill Jews and other civilians by the millions. However, if you were an Allied soldier, your chances of getting sent to a concentration or death camp like Auschwitz were slim, so you did not have to worry about dying from a chemical weapon.

The Japanese, however, did use chemical weapons in a limited manner on the battlefield during the war, specifically in the Sino-Japanese conflict. Because of this, the only soldiers who were in danger of dying from chemical weapons during World War II were the Chinese. The use of these weapons was hugely controversial, and the Japanese destroyed most of their records after the war. In 2019, however, the discovery of a detailed report of the use of blistering agents was revealed. It listed the number of shells containing chemical weapons that were fired at the Chinese. While the lack of information makes it impossible to know how many soldiers died, it is likely at least some were killed by the effects of the chemical weapons.

Death marches were cruel and common

Despite new rules that were supposed to prevent the mistreatment of POWs, they often suffered horribly. One of the most shocking acts was the forced death marches to which POWs on both sides of the conflict were subjected. These were forcible transfer marches over dozens of miles, through difficult terrain and bad weather. Fresh from battle, troops were exhausted and often injured, resulting in the deaths of thousands before these marches reached their destinations.

The infamous Bataan Death March (pictured) saw 78,000 Filipino and U.S. troops forced through the jungle to a POW camp 65 miles away. After weeks of fighting, they were sick, some near starvation, and exhausted. Along the way, they were beaten for no reason, given hardly any food, and shot if they asked for water. The Sandakan Death Marches saw Australian POWs forced to march over 150 miles through the jungle of Borneo. If they died on the journey, their bodies were left where they fell. Those who couldn't continue walking were murdered. One British officer who survived the Lamsdorf Death March wrote about the freezing temperatures, desperate hunger, fear, and death on the months-long march. He also related that a Russian group of POWs had started on their own march, but were shot and killed by planes from their own country.

The Soviets forced the Germans on their own death march from Stalingrad. In the dead of winter, with little to no food, many German POWs died.

Fragging was uncommon but tragic

During the Vietnam War, there emerged a seemingly new problem for the military. Under the stress of that conflict, soldiers were snapping and killing their superior officers. This became known as "fragging," named after the type of grenade that was sometimes employed to do the killing — soldiers would lob a frag grenade into the tent of the officer they wanted dead.

While the term was not coined until the Vietnam War, the act of killing a superior officer, usually over a personal slight, did occasionally happen during WWII. Very rarely during the war, they even included grenades, although nothing in number compared to what would happen in Vietnam. The stories are overwhelmingly tragic. Lieutenant Harold Cady was killed by a terrified Private Herman Perry when he tried to physically discipline him in Burma. Perry was Black, had been in trouble before, and was afraid to go back to prison. Cady knew he couldn't show mercy in front of other soldiers. Perry shot Cady in the stomach, before going on the run. He was eventually captured and hanged.

In France, Private George Green Jr. shot and killed Corporal Tommie Lee Garrett for seemingly no reason, other than Green wanted to hurt someone that day. Green's defense was that Garrett had accused him of spilling urine on the ground and grabbed him when he ordered Green to clean it up. A witness claimed Garrett had held a knife during the encounter. Green was found guilty and executed for his crime.