Weird Things People Ignore About Davy Crockett

Davy Crockett is nothing short of an American icon. It's a striking, collective mental image: the brave Crockett, setting out into the wilds of Tennessee and the unknown and unexplored (by European-American settlers) areas west, brandishing a rifle and wearing a coonskin cap. Or, there's the notion that he died fighting at the Alamo, one of the most legendary battles in North American history. At any rate, Crockett lived a life of danger and adventure that coalesced with a period of significant and rapid change in the United States: the early 1800s.

Due to a combination of self-aggrandizement and contemporary accounts of his achievements that may have stretched the truth for entertainment and political purposes, it's hard to separate truth from fiction (or mythology, or lore) when it comes to the spectacular life of Davy Crockett. Much of the common knowledge about the 19th-century celebrity, statesman, frontiersman, and warrior was perpetuated by movies and TV, and there are a lot of lies about Crockett floating around. However, Crockett's actual life was documented enough that we're able to determine and pass on some of the more curious, harrowing, and altogether baffling moments. Here are some things that unequivocally really did happen in the life of Davy Crockett, and they sure are weirder than anything that's been part of the so-called official record passed down by biographers and filmmakers.

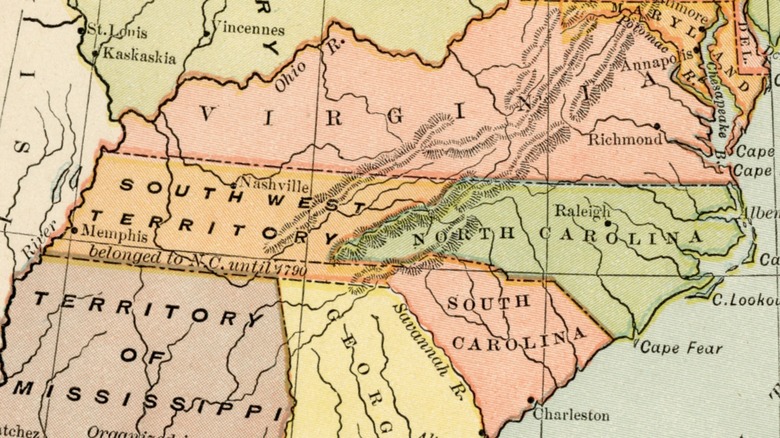

He was born in a state that isn't real

While he'd come to be strongly associated with the region of the United States where the South meets Appalachia, Davy Crockett wasn't born in either of those states. At least, not according to his politically active family, he wasn't. In August 1786, Crockett was born in what's now Eastern Tennessee, but which at the time was considered part of Franklin, a proposed U.S. state that never happened.

The far-flung residents of isolated Western North Carolina decided to create a new state in 1785, based almost entirely on the single issue that doctors and lawyers were too intellectually different from the common man and shouldn't be allowed to serve as legislators. People in the area wanted their proposed new state to issue that prohibition. Contingents from the 13 colonies cast their votes, but the threshold didn't meet the required two-thirds majority. The state of North Carolina refused to recognize Franklin, which had trouble assembling a necessary militia anyway and absorbed it in 1789, right around Davy Crockett's third birthday.

An attack on a schoolhouse bully went terribly awry

At the age of 13, and at his father's behest, Davy Crockett began attending a rural school near his family's home in Franklin County, Tennessee. Almost from the immediate outset, it was a desperately unpleasant experience for Crockett and one which would lead to his departure from home long before he'd intended. "I went four days and had just begun to learn my letters a little, when I had an unfortunate falling out with one of the scholars — a boy much larger and older than myself," he recalled in "Davy Crockett's Own Story as Written By Himself." Crockett decided to wage a one-person anti-bullying campaign on his unnamed attacker through the act of pre-emptive self-defense. "I concluded to wait until I could get him out, and then I was determined to give him salt and vinegar."

On the appointed day, Crockett hid in some bushes by the side of the road near the school, awaiting his bully on his evening walk home. "After awhile, he and his company came on sure enough, and I pitched out from the bushes and set on him like a wild cat. I scratched his face all to a flitter jig, and soon made him cry out for quarters in good earnest," Crockett wrote.

Davy Crockett ran away from home

His bully vanquished, Davy Crockett then considered the ramifications of his actions. Fearing that his schoolmaster would physically punish him for his retribution, Crockett took to hiding in a nearby wooden area for the entirety of several school days. When a note about his truancy reached Crockett's father, he once again feared physical violence at the hands of an adult.

Threatened by a beating at home, and likely one at school, where his bully remained at large, Crockett didn't go back to school as directed but ran away instead. "I then cut out, and went to the house of an acquaintance a few miles off, who was just about to start with a drove. His name was Jesse Cheek, and I hired myself to go with him," Crockett wrote in "Davy Crockett's Own Story as Written By Himself."

For nearly two years, Crockett worked as an itinerant laborer, his family unaware of his whereabouts. When he returned home at age 15, he claimed that some members of his family at first didn't recognize him.

He was really good at hunting bears

The five-part miniseries "Davy Crockett" aired on ABC's "Disneyland" anthology series in 1954 and 1955 and was so popular it started a Davy Crockett fad, with Americans buying up truckloads of coonskin caps and sending three different versions of the theme song "The Ballad of Davy Crockett" into the pop chart Top 10 simultaneously. That tune offered the bodacious claim, taken as fact, that Crockett was such a skilled and fearless outdoorsman that he once "killed him a bear when he was only three." Crockett probably didn't fell a gigantic wild animal as a toddler, as there's no reliable historical record attesting to that fact. There's not even a discussion of it in the braggy 1813 autobiography "Davy Crockett's Own Story as Written by Himself."

In his days as a young frontiersman, he claimed in his book to have killed 10 bears in a single spring. In late 1825, Crockett was invited to hunt on an acquaintance's vast, bear-infested property. "He said they were extremely fat, and very plenty, and I knowed that when they were fat they were easily taken, for a fat bear can't run fast or long," Crockett wrote. Over the span of two weeks, Crockett and his eight dogs successfully hunted 15 bears, he claimed. By the end of the bear-hunting season, Crockett had taken down a grand total of 105 bears, by his count.

He could've died in a boat crash

Following a loss in a Tennessee legislature election bid in 1825, Davy Crockett got into the business of barrel-making, overseeing the construction of wooden components called staves which were then sent down ships in the Mississippi River to be sold in New Orleans. In the spring of 1826 — after leaving the operation to go on his bear-hunting spree that left 105 animals dead — Crockett agreed to personally escort his crew and its cargo of 30,000 staves on the journey to market.

After an uneventful opening salvo on the smaller Obion River, the boat hit the choppy and aggressive waters of the Mississippi River, and Crocket learned that the ship's operator barely had any piloting experience. The crew got upset, and as the boat kept trepidatiously moving down the Mississippi River, another ship allowed Crocket to attach itself for extra security and guidance. That made for two unsteady boats, and Crockett retreated into a cabin to sulk. As he was inside, the overhead hatch broke down, sealing Crockett in the chamber. Immediately after, the two lashed-together boats hit the underwater portion of a small island, causing everything to sink. Crockett was rescued by his crew, who pulled him out of a small hole in a cabin wall, all of his clothes getting pulled off as he emerged. There were no casualties in the accident, but all 30,000 staves were destroyed.

A play made Davy Crockett famous

Life for explorers in the Wild West was tough, and Davy Crockett's adventures therein didn't become such an indelible and thrilling part of the American canon of history and lore until well after they happened. Crockett's frontier-set episodes, hunting excursions, daring face-offs, and inspiring self-sufficiency weren't well known to the public until the 1830s, thanks to James Kirke Paulding's 1831 play "The Lion of the West." Crockett had served as a state legislator in Tennessee and won a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives by the time that theatrical work was first performed at the Park Theater in New York City. A barely disguised portrait of Crockett during his early years, "The Lion of the West" concerned a brave and daring fellow named Colonel Nimrod Wildfire, portrayed by acclaimed stage actor James Hackett.

As the entertaining play filled a theater every night, the demand for "The Lion of the West" stoked interest in the inspiration. Two years after the play's long run began, the first of many truth-stretching Crockett biographies was published, "Sketches and Eccentricities of Colonel David Crockett of West Tennessee."

He was a really good fiddler

There's a difference between the fiddle and the violin, and Davy Crockett was evidently a master of the former, or as it was known on the early 19th-century frontier, a "devil's box." He was known to have taken his instrument on long voyages into the wilderness as well as into battle. Written accounts of what would be his last days during the Battle of the Alamo in 1836 recount Crockett providing comfort to the Texans in the form of familiar old folk songs as they fought the attacks of Mexican troops, or playing danceable songs as entertainment during down periods. "Col. Crockett was a performer on the violin, and often during the siege took it up and played his favorite tunes," Battle of the Alamo survivor Susanna Dickinson said in "The History of Texas from Its First Discovery and Settlement" (via True West Magazine).

It could be apocryphal, but historical texts suggest that Crockett played the fiddle during some of his last moments. After General Santa Anna ordered the last captured defenders killed, his buglers performed their execution song called "El Deguello. At that moment, Crockett supposedly struck up "The Tennessee March."

Davy Crockett loved all kinds of Betsys

Davy Crockett was often the subject of portraits and other paintings during his lifetime, and he was frequently shown holding a shotgun. Any of those guns may have been identified as Betsy, a name Crockett bestowed on his favorite firearms more than once. As a gift commemorating his time in the Tennessee State Assembly in the 1820s, Crockett received from his supporters a flintlock rifle that he called "Old Betsy." Betsy is an affectionate and diminutive version of Elizabeth, a name shared by both one of Crockett's wives and one of his sisters. Nearly two centuries later, it remains unclear which woman (if any) was the namesake for "Old Betsy."

The same can be said of another of Crockett's most treasured guns, "Pretty Betsy," although some records say it had been named "Beautiful Betsy." That one, a cap rifle, was given to Crockett by Whig Party officials in Philadelphia in 1834. While Crockett trusted both guns, he found them both to be such important personal heirlooms that he handed them over to associates before he left to fight, with other firearms, at the Battle of the Alamo in 1836.

He played up the outdoorsy image

Form a mental picture of Davy Crockett, and it's one of a rugged outdoorsman in the woods or the mountains, a fur cap on his head as he explores the wilderness or fights a bear. That's the popular conception of Davy Crockett because of popular entertainments like the 1950s "Davy Crockett" television series, and also because Crockett cultivated it himself.

When the intensely successful 1831 play "The Lion of the West" first made Crockett a household name, he was well into his 40s and long past his days as an active explorer and voracious hunter who set out into the wilds of Tennessee for big chunks of time. To give the people what they wanted, which was the Crockett depicted in and mythologized by projects like "The Lion of the West" and his own autobiography, Crockett posed for portraits in the trappings of his youthful conquests. He'd hold up a rifle so he could be painted that way, or surrounded by dogs, or in the midst of a staged scene that looked like he was hunting.

He sabotaged his career by speaking out in favor of indigenous people

Having fought alongside military commander Andrew Jackson in the Creek War and the War of 1812, Davy Crockett was a supporter and ally when his colleague was elected president in 1828. Crockett emphatically withdrew his support following the passage of the Jackson-championed Indian Removal Act of 1830. That action was the cause of the Trail of Tears, an appalling and harrowing moment in American history in which Indigenous people were forcibly evicted from their land.

In his 1831 bid for a third term in the U.S. House of Representatives, Crockett campaigned on anti-Jacksonian rhetoric, but the president and his policies to expand the nation for European-Americans were very popular with the people of Tennessee, and Crockett lost his spot in Congress. He returned to the House as a member of the rival Whig Party in 1833, and he continued to oppose Jackson's methods. In 1835, voters again expelled Crockett from the House of Representatives.

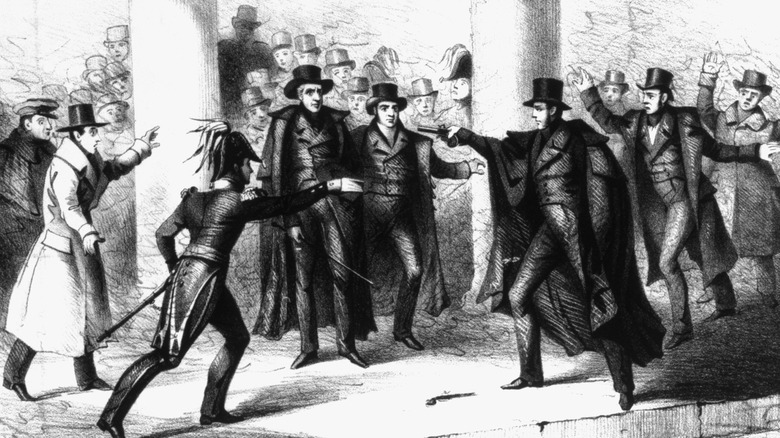

Davy Crockett saved Andrew Jackson's life

In 1835, Davy Crockett was serving out what would be his final two-year term in the House of Representatives. On January 30 of that year, he was among the attendees of a state funeral on the grounds of the U.S. Capitol building held for the late representative from South Carolina, Warren Davis. Despite a contentious and adversarial relationship with Congress at the time, President Andrew Jackson also attended the solemn event alongside Crockett, one of his primary and most outspoken political opponents.

As the group of high-powered politicians exited the building and walked past the East Portico, a would-be assassin named Richard Lawrence jumped out of the crowd of mourners and observers and opened fire at President Jackson. Or, at least he tried to shoot the sitting president. Both of Lawrence's pistols malfunctioned in the moment, allowing the targeted party and his associates to subdue the attacker. Witnesses say that Jackson, in poor health and needing the aid of a cane at the time, used that walking aid to give Lawrence a thorough whacking. Crockett, meanwhile, set aside any animosity he had for Jackson and his policies to do what he could to prevent Lawrence from continuing his assassination attempt. Along with U.S. Navy Lt. Thomas Gedney, Crockett physically overpowered Lawrence and helped get Jackson safely into the carriage and whisked him away to safety.

It's not clear how he died at the Alamo

Davy Crockett was so embittered by his final electoral loss that he left Tennessee entirely in November 1835. "You may all go to hell and I will go to Texas," he said, according to Texas Standard. He headed to the disputed Southwestern territory at the peak of the Texas Revolution, waged between American slaveholders who wanted independence for the region and the Mexican government, which staked a claim to the land. And that's what the Battle of the Alamo was really about. Crockett settled in San Antonio in February 1836, pledging loyalty to the Texas Republic and getting an assignment to help defend the Alamo.

Within days of Crockett joining, forces led by Mexico's General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna stormed the fort, killing about 200 soldiers and their allies. It's something of an unresolved mystery just how and when Crockett died. The only adult to survive the Battle of the Alamo was an enslaved person identified only as Joe, and he testified to seeing the identifiable body of the very famous Crockett amidst the dozens of other war dead. Then unconfirmed reports of Texans surrendering to Mexico appeared throughout newspapers of the day, counting Crockett among that contingent. A postmortem Crockett biography "Col. Crockett's Exploits and Adventures in Texas," found to have taken great creative liberties with the story, popularized many myths about Crockett, and also claimed that Crockett was shot after his capture.