Things About The Battle Of The Alamo That Don't Make Sense

It's the 13 days of glory, the most famous and celebrated moment in the struggle for Texas independence: the siege and Battle of the Alamo. Books, songs, paintings, and films have turned the battle into an epic struggle for freedom and made heroes of the Texian defenders of the fort. For many, it's the only event of the Texas Revolution they're likely to be familiar with, and largely through such laudatory cultural works.

Any event so mythologized is going to leave some people questioning just how accurate the movies and other depictions are. Indeed, there's a cottage industry of historians who have taken up the task of challenging the romantic storybook version of the Battle of the Alamo. Some of these historians remain sympathetic to the Texian cause, admiring their ideals and praising their heroism even when dispelling popular myths. (For example: Davy Crockett wasn't a commander at the Alamo.) But others have advanced a revisionist account, one that paints the Alamo and the Texas Revolution as a despicable land grab by American enslavers and outlaws.

Revisionist accounts can be animated by the same zeal, idealism, and bias as heroic celebrations, and in the case of the Alamo, the messed up truth of the Texas Revolution is more complex than either extreme. But setting aside cultural, moral, and political concerns, there is much about the battle that is confusing, nonsensical, or ironic. Here are just a few things about the Battle of the Alamo that don't make a whole lot of sense.

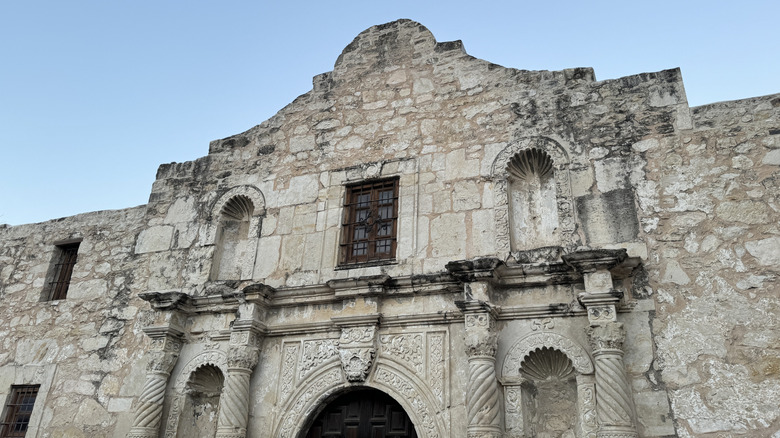

The Alamo was never meant to be a fort

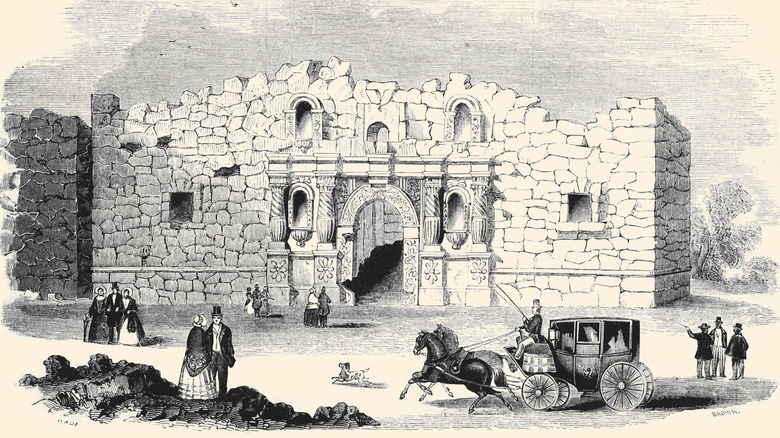

The Alamo is one of the most famous forts in American history. Many people know it only as a fort. But it wasn't designed to withstand sieges or launch combat. It wasn't designed with military purposes in mind at all. The Alamo — which was originally named San Antonio de Valero — was meant to be part of the Spanish mission chain. It was established in 1718 and relocated in 1724. Like other missions, it was a complex of Catholic buildings within outer walls, intended to provide refuge for travelers and convert Native Americans to Christianity.

The administrative and educational buildings of Valero were functioning within a few years. The intended church, on which construction began in 1744, was never completed. Valero was paired with the nearby presidio (fort) of San Antonio de Bexar, but as Bexar was never adequately fortified, so too was Valero never properly established. No religious services were ever performed in the half-finished church, and the population of converts fluctuated. Spain secularized its Texas missions in 1793, and Valero fell into decline.

The crumbling mission was re-purposed in various ways over the years. Natives and Tejanos (Texans of Mexican descent) sometimes squatted behind the walls, and visitors to the growing town of Bexar remarked on the romantic image of the ruins. But after the Louisiana Purchase, Spain dispatched soldiers to occupy the mission, and it was at this time that it became known as the Alamo, for the soldiers' hometown of Alamo de Parras.

Americans didn't fortify the Alamo

One of the great ironies of the Alamo is that a fort that was really a ruin, famous as the last stand of a band of Texians against the Mexican army, was largely fortified by Spanish and Mexican hands. The process of converting the decaying mission into a military structure began around 1803, when a Spanish garrison was ordered there in the wake of the Louisiana Purchase; Spain feared that French and American settlers would begin encroaching on Mexican territory.

The Alamo Company, as the garrison became known, established barracks and a hospital (the first in Texas) at the old mission and remained there through the Mexican war of independence. In October 1835, with unrest in Texas growing, the Alamo was occupied by Mexican troops under the command of General Martín Perfecto de Cos. Per Frank Thompson's "The Alamo," Cos and his approximately 1,400 men made significant improvements to the Alamo as a fort, building ramps up to the apse to mount three cannons, shoring up crumbling walls, and erecting a palisade between the church and the south wall.

For all that work, Cos ultimately failed to hold the Alamo. A band of Texians under the command of Stephen Austin laid siege to San Antonio de Bexar and the Alamo with it. Dwindling food supplies and monotony did more damage to the morale of Cos' men than the limited scrapes he fought with the Texians, who were themselves plagued by boredom and disobedience. After a little over a month of such frustration, a bloody skirmish in December delivered town and fort into Texian hands.

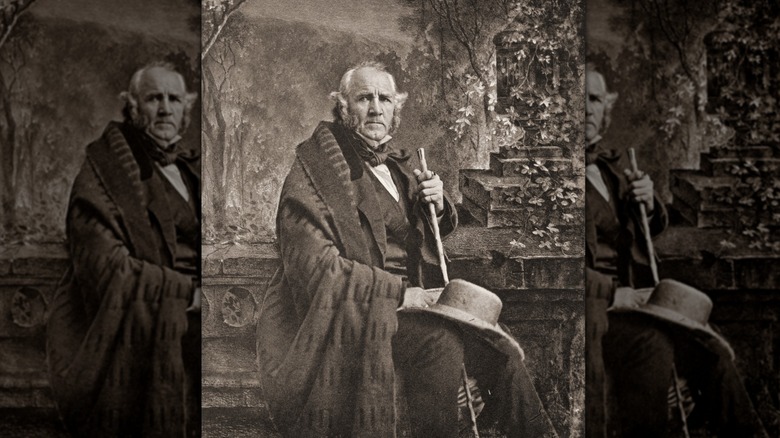

Sam Houston wanted the Alamo destroyed

A widespread myth about the siege and Battle of the Alamo, central to John Wayne's 1960 film, is that the defenders were buying time for Sam Houston to build up the Texian army. But in the two weeks that the Alamo garrison held out against the Mexican army, Houston made little progress in recruiting or training troops; to the extent we can reconstruct his actions at that time, he seemed more focused on drumming up support for a political convention.

Far from benefiting from the siege of the Alamo, Houston had long opposed trying to hold it at all. He'd objected to the siege of Bexar with sound logic: The town had a majority Tejano population (with many residents loyal to Mexican dictator Santa Anna) and was too far removed from Anglo-Texian strongholds and communication lines. Moreover, as the defeat of the Mexican garrison demonstrated, the Alamo couldn't be held even with more than 1,000 men, let alone Bexar. As commanding general of the Texas regular army, Houston sent James Bowie to retrieve the cannons from the Alamo, evacuate the town if necessary, and destroy the old mission.

But Houston's reasoning meant little to the men stationed at the Alamo, who had fought to win it and saw even a strategically sound retreat as a defeat. Houston also had no legal authority over the fiercely independent volunteers. Bowie, a volunteer himself, once called Bexar home. Sentiment, the enthusiasm he found among the Alamo defenders, and the lack of draught animals to get the cannons safely away, all convinced him to disregard his orders and hold the fort.

The Alamo had no strategic significance for the Texians

If holding the Alamo didn't buy time for Sam Houston to build up the Texian army, what military aim did it achieve? In justifying his decision to throw out his orders and stay in the mission, James Bowie wrote that the Alamo and San Antonio de Bexar were key to securing an independent Texas. "It serves as the frontier [piquet] guard," he declared (per Texas Monthly), "and if it were in the possession of Santa Anna, there is no stronghold from which to repel him in his march toward the Sabine." The logic being that the Alamo functioned as an early warning against Santa Anna's approach and could harass his armies, pinning them down with artillery fire.

The idea was not without merit. But as Houston had already pointed out, the Alamo was short on men and provisions for such an operation. Committing the necessary resources meant pinning down perhaps thousands of soldiers in enemy-friendly territory to hold a town that had already fallen despite having such a garrison. Given the fragile and fractious nature of the rebellion, concentrated farther north, a piquet guard at the Alamo offered no real military advantage.

Bowie also framed his decision to stay at the Alamo as necessary to protect the civilians of his former home. Having married into a prominent Tejano family, and with relatives still living in Bexar, he could be expected to want to protect them. But Bexar was only in danger from Santa Anna's forces because Texian rebels, both Anglo and Tejano, were stationed at the Alamo. Remaining there put everyone, civilians included, at risk.

The Texians had to be kept from fighting each other

Throughout history, commanders of armies have struggled to get their men to fight. During the Texas Revolution, the leaders of the rebels struggled to keep their men from fighting each other. Far from a unified group of freedom-loving Americans, the Texas Revolution was led by men who were frequently at odds with each other. One of Sam Houston's great frustrations as commanding general was the political squabbling above him. Below him, independent-minded soldiers and volunteers frequently treated orders as suggestions and often clashed with their commanders and each other.

At the Alamo, this tension showed itself most between enlisted men and the volunteers. Nominally, command of the garrison fell to Colonel James C. Neill, who left in early February on personal matters. But he only ever held real command over the regular soldiers; the volunteers flocked to James Bowie. For Lieutenant Colonel William Travis, who was left in charge after Neill's departure, it was an untenable situation, one he complained about in letters to his superiors.

Eventually, the choice of commander was put to the garrison, who elected Bowie. He and his faction celebrated by getting drunk and releasing everyone from the Bexar prison. This did nothing to quell internal hostilities, and Travis and the regular soldiers even withdrew from the Alamo to camp outside Bexar for a time. But Bowie sobered up on Valentine's Day 1836, rode out to Travis' camp, and made his amends. The two agreed to a joint command, an arrangement which held until Bowie fell ill during the siege.

The Alamo defenders didn't see the Mexicans coming

James Bowie may have exuded confidence in the Alamo's effectiveness as a piquet guard against Santa Anna in his letters, but neither he nor William Travis was ready for a significant conflict. They were aware of this; surviving messages from well before Santa Anna's arrival in San Antonio de Bexar show them asking their fellow rebels for men, arms, and supplies. But Bowie and Travis also assumed — wrongly — that they would have ample time to receive such support.

It was conventional wisdom that any major military campaign would operate in the spring or summer. After expelling the Mexicans from the Alamo and Bexar, the Texians assumed they wouldn't be back until the warm weather came. That attitude was exactly what Santa Anna was counting on; he whipped up plans for a wintertime blitz to put down the Texas Revolution and the troublesome Anglo settlers once and for all. He also chose a grueling but relatively quick march over a sea landing, the better to catch the Texians off-guard.

Tejano scouts reported Santa Anna's advance to Travis and Bowie, but they assumed the Mexican army couldn't arrive before mid-March. They made almost no effort to gather food and supplies in the Alamo, or to clear the surrounding brush to limit enemy cover. The garrison even joined the townspeople of Bexar in celebrating George Washington's birthday on February 22. Santa Anna was on them the next day, and only a lookout's keen eye allowed Travis and Bowie to manage a hasty retreat into the Alamo.

The Alamo defenders were unprepared for a siege

While Santa Anna caught the Alamo defenders by surprise, his army's long line of march made a siege inevitable. Such a conflict was monotonous and wearisome for the Alamo garrison. Constant artillery fire deprived them of sleep (though there were no casualties), and constant pleas for reinforcement were met largely with silence. It would have been a trying set of circumstances even if the Alamo had adequate men and provisions, but it was sorely lacking in both.

According to J.R. Edmondson's "The Alamo Story," last-minute foraging and scavenging had brought enough beef and corn into the Alamo to last roughly a month when stretched. Even so, rations were thin, and by the 12th day of the siege, hunger was becoming an issue. Just as pressing was a lack of ammunition. The defenders had plenty of muskets and cartridges, but the gunpowder for the cannons was questionable. Lacking cannonballs, the garrison improvised with whatever bits of shrapnel they had lying around.

Even the Alamo itself was unprepared for a siege. Despite the impressive work done by the Texians, and the Mexicans and Spanish before them, the fort was still a converted, half-ruined mission, and the ravages of time and warfare combined were chipping away at it. The north wall was already crumbling and needed to be reinforced with a palisade; by the end of the siege, part of it collapsed entirely and had to be quickly mended.

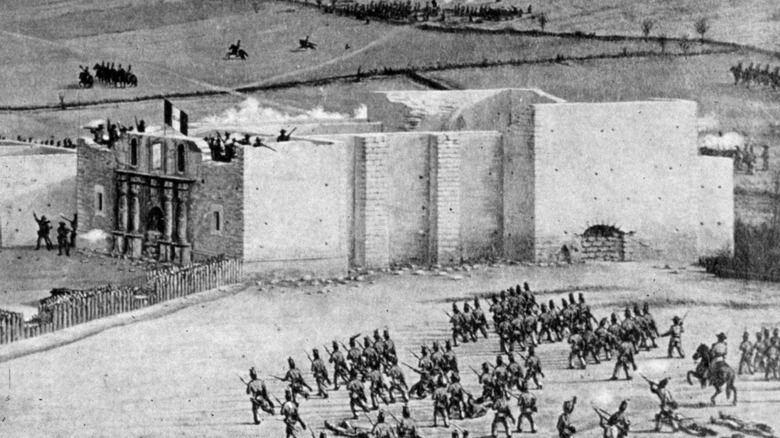

Santa Anna didn't need to sacrifice his men to take the Alamo

By March 5, 1836, it was obvious that the Alamo garrison couldn't hold out for much longer. The defenders were exhausted, hungry, and increasingly demoralized. Though commander William Travis put up a defiant front in his letters to the outside world, he appears to have tried for an honorable surrender, sending a local Tejano woman into San Antonio de Bexar with a message for Santa Anna.

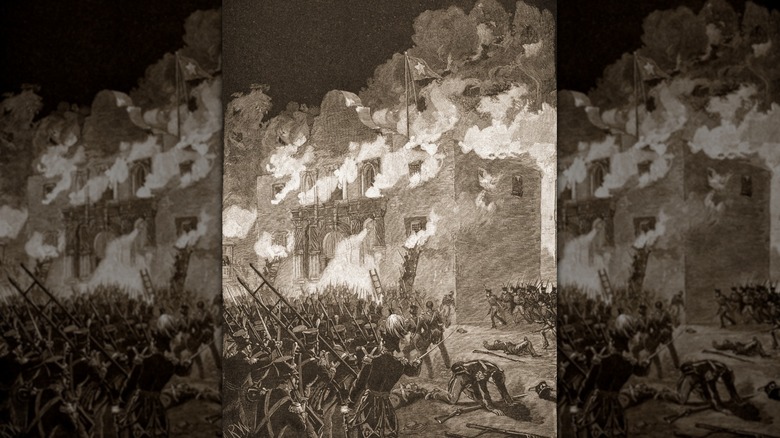

Santa Anna furiously rejected any idea of a negotiated surrender. He had branded the Texian rebels as pirates and wanted to make an example of them. But to do so didn't require any significant cost to his forces. In the Mexican army's supply chain were two 12-pound cannons. Together, they could reduce the Alamo walls to rubble within a matter of days. And Santa Anna's officers pointed out to him — as Sam Houston had to the Texians — that there was no strategic value to the Alamo, certainly none worth losing their soldiers' lives over.

Santa Anna overruled the majority of his staff, refusing to consider waiting for the cannons. Far from being moved by the possible deaths among his men, some in Santa Anna's army felt that Travis' proposed surrender only spurred the general on. "He wanted to cause a sensation," wrote José Enrique de la Peña (per J.R. Edmondson's "The Alamo Story"), "and would have regretted taking the Alamo without clamor and without bloodshed, for some believed that without these there is no glory."

No one agreed on how many people were killed in the battle

There's no question that the Alamo garrison died to a man (though women and children were inside the Alamo as well, and were spared). But there has been some question in recent years as to how many defenders there were. Many accounts, not to mention film and song, have the garrison down at around 180 fighting men. But José Enrique de la Peña's diary listed 253 Texian dead, well in excess of that number. Recent research has gone through the tallies of fighters kept by William Travis, and while a precise number remains elusive, some historians have put the Alamo garrison down as above 200 men at the time of the battle.

There are also discrepancies about the number of Mexican dead. The afternoon after the fighting, Santa Anna dispatched his official report, in which he claimed only 70 of his soldiers had died and an additional 300 were wounded, numbers that match up with some of his officers' reports. But de la Peña recorded 311 of his fellow soldiers as dead, while contemporary American reports said up to 3,000 had died. Several historians concede a great amount of uncertainty, but the best estimate seems to be somewhere between 300 and 600 dead and wounded if casualties during the siege are included. A significant number of the deaths were likely due to poor medical planning by Santa Anna and by friendly fire from unprepared soldiers shooting in the dark.