What Hitler Planned To Do With The U.S. If He'd Won WWII

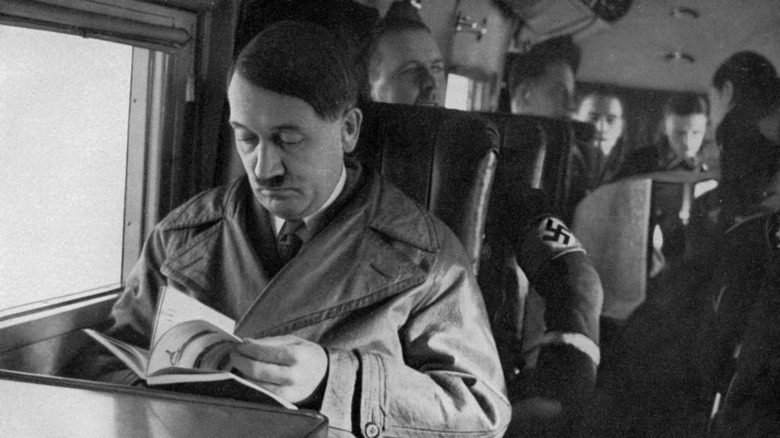

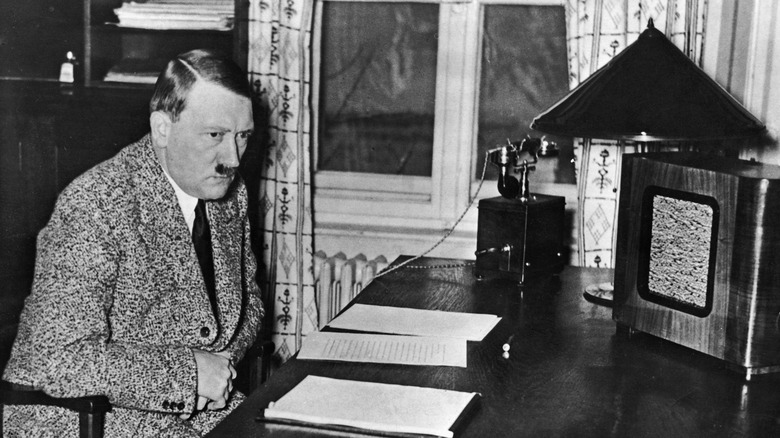

With the distance afforded by history, it may seem like the Allied win in World War II was a done deal. But, at the time — or, at least, in the earliest years of the war — things were not so certain. Adolf Hitler, the dictator of Nazi Germany who became the nation's chancellor in 1933, sure seemed to be on the rise. With his loudly proclaimed notions of racial purity and stated desire to gain ever more land for the German people, he set about invading neighboring nations and engaging in a campaign of European domination, as well as enabling the genocide known as the Holocaust.

Eventually, even those separated from the Nazis by great landmasses or oceans began to worry. Would Hitler make a grab for Britain? The Soviet Union? Yes, if attacks like the Blitz and the ill-fated Operation Barbarossa were anything to go by. Naturally enough, some wondered if he had even plans for territory farther afield, including the United States.

An invasion of the U.S. would have been a tremendous task, but there are hints that Hitler and other Nazis may have been toying with the idea of somehow striking America. Why else would Hitler have made speeches in which he dreamed of teaming up with Britain against the U.S.? Why else would he have ordered the development of massive warships and long-range airplanes (including the Amerikabomber program) if not to prepare for a future showdown? Here's what Hitler may have done with the U.S. if WWII turned in his favor.

Hitler saw the U.S. as potential competition early on

Though he never fully fessed up to it, Hitler's recorded words make it pretty clear that he saw the U.S. as a rival fairly early on. In an unpublished sequel to "Mein Kampf," written in the late 1920s, Hitler argued that the U.S. was in an expansionist frame of mind. He and the Nazis were allegedly working to "counter the union of the American states with a European one, in order to prevent the world hegemony of the North American continent" (via The National WWII Museum). This was framed as a fight for Lebensraum, or "living space" for German people. That notion was established well before the 20th century, but proved to be a key concept as the Nazis seized land, made war, and committed genocide.

In a July 1941 meeting with Japanese ambassador General Hiroshi Oshima, Hitler more clearly reiterated his stance and pushed for an alliance with Japan against an increasingly powerful U.S. "America is pressing with its new imperialist spirit sometimes in the European, sometimes into the Asian Lebensraum," he said. Hitler claimed that Germany and Japan were beset by Russian and American imperialism on different fronts. "Therefore he [Hitler] is of the opinion that we must jointly annihilate them," the account noted (via The Journal of Modern History).

Later, he would also acknowledge the industrial power of the U.S., as well as its industrial use of technology and the advantages it represented, even after declaring war on the nation in December 1941.

Early on, he thought America was a source of racial purity

Though Hitler planned to face off against the U.S. one day, he also once thought that it contained the seeds of an ideal society. He pointed to so-called "Nordics" who had emigrated to the U.S. and had allegedly established themselves as industrious, upstanding members of their communities. European nations, in turn, were allegedly experiencing a drain as these people moved away, making these places easier targets for Hitler (however, he also bemoaned the loss when Germans left for America). In "Mein Kampf," he even wrote that "The racially pure and still unmixed German has risen to become master of the American continent" and would remain as such so long as they kept that "unmixed" status (via "Neither Settler Nor Native"). However, given the rise of anti-German sentiment in the aftermath of the First World War, Hitler's assessment of German-American power rings rather hollow.

Beyond this unsupported claim, he also reserved special praise for restrictive immigration laws imposed by U.S. authorities, which supposedly preserved the "purity" of the nation. This is in part what led Hitler to once see the U.S. as a formidable potential opponent, leading him to push for a strong European empire — led by him, of course — as a way of standing against an ascendant American power.

Hitler's changing views made him believe the U.S. was a weakened target

Though Hitler once thought of the U.S. as a formidable opponent that would require serious planning to defeat, his views on that front had changed dramatically by the 1930s. By this decade, he had come to believe that the U.S. had succumbed to the mixing of races. Where some have since touted this diversity as a special strength of American culture, Hitler saw it as a sign of a fundamentally degenerate society that, if he played his cards just right, was going to be easier to pick off in the future.

Hitler mused that this diversity had somehow led to a fundamentally weak economy, a fatally dysfunctional political system, and the lack of a real culture. Not all Germans agreed on that last point, at least; for instance, Black American innovations like jazz were majorly popular in prewar Germany, and top Nazis occasionally whined about the music style and attempted to ban it.

Still, despite vocally dismissing the potential power of the U.S., it's not as if Hitler and company were kicking back and lazily preparing for an easy win against the country. He wrote of the relatively large size not just of the U.S. as a nation, but of its economy, which he believed would allow it to weather economic shocks and grow more independently than those of European nations. So, while it was weakened in Hitler's view, neither was the U.S. a fully neutralized threat.

He expected war between a unified Europe and the U.S.

What precisely did Hitler plan for the U.S. in his fantasy of the long-term future? It's unclear, but some have argued that he had a general framework now known as the Stufenplan, or stepping plan. Though there's no evidence that Hitler or other Nazi officials called it that, there are indications that they were planning to methodically take over territories in Europe in the process of building an empire. It's speculated that one of the later steps in the Stufenplan would have to be a confrontation between this empire and the United States.

After all, if Hitler and his followers managed to complete some of the first steps in this plan and really set themselves on the road to becoming a major power, war or some sort of showdown with the U.S. was all but inevitable. To even dream of winning such a conflict, the Nazis would have to command quite a lot of territory, resources, and people.

Hitler recognized the possibility by the time he wrote his second book in the late 1920s. Though it was unpublished during his lifetime, the document was made public by 1961 and includes his stated assumption that Germany would fight the U.S. somehow. However, given the ways in which Nazi policy changed — sometimes dramatically, sometimes suddenly — it's hard to decide just how much weight we should give this document. He is hardly regarded as a great strategist with an eye on the long-term, after all.

Plans for an attack on the U.S. were hampered by geographic size and distance

Given the muddiness of Hitler's long-term plans, historians have plenty to argue over when it comes to whether or not he really wanted to dominate the entire world. But what is clear is that, if he ever really entertained the notion of somehow ruling the whole planet or at least striking the U.S., there was one serious obstacle: geography. Specifically, U.S. territory was both really, really big and an entire ocean away.

Getting across the Atlantic and establishing dominance over a humongous territory was daunting and would have stretched the limits of both the German air force and its navy. Or perhaps the whole idea was so far-fetched that it was laughable, as Hitler tried to play it off in an interview with a reporter from LIFE in 1941. Speaking to reporter John Cudahy, he claimed that such an invasion was about as likely as Nazis making it to the moon.

Even if he secretly considered it, there was the matter of the U.S. Navy, which was large and well-armed compared to Germany's naval forces. Traveling across the ocean to face such a force could prove devastating. Defeating the Americans at sea wouldn't just require boosting numbers of ships or sailors, but strategic placement of air and naval bases along the European side of the Atlantic. This is precisely what Hitler was doing in 1941, after taking France but before declaring war on the U.S.

He publicly derided the idea of invasion when asked

While Hitler was grabbing territory and sort-of subtly building up bases and naval forces through 1941, he wasn't really talking about it to the press. Yes, by April of that year he had secretly promised Japan that Germany would go all-in on declaring war against the U.S. if Japan did the same. But the public side of Hitler instead played his actions off as a simple defense of Germany and its people. Any suggestion that he had his sights set on something else was laughable. Cue him telling LIFE reporter John Cudahy that he might as well send Nazis to the moon as invade the U.S. or anywhere else, really.

As much as Hitler may have wanted to put people off their guard, he might as well have had his fingers crossed behind his back during the Cudahy interview. While denying his expansionist plans, he likely hope to distract the Allies, then build up forces, supplies, and other practical considerations for war. If the interview could be part of a propaganda campaign to convince Americans that Hitler wasn't such a bad guy, all the better.

Only, by this point, FDR was openly warning America of the imminent danger posed by the Nazis. By the end of 1941, with the Pearl Harbor attack and Germany's declaration of war against the U.S. shortly after, it was clear that his intentions against the U.S., whatever they truly were, had never been a laughing matter.

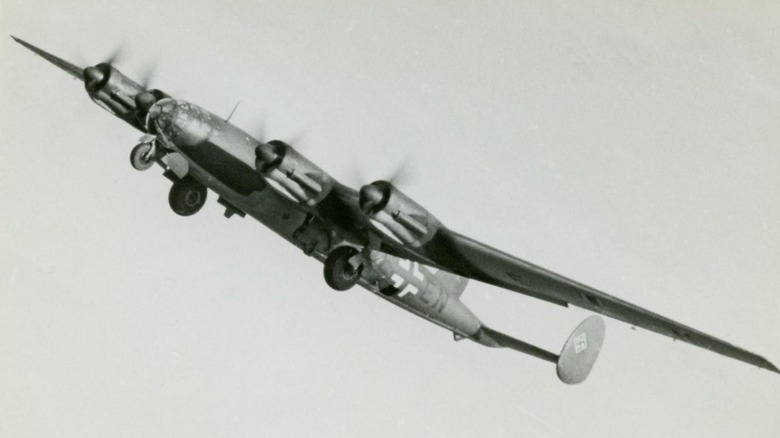

Bombing was part of the plan

While the ocean between Germany and the U.S. was beyond the range of the German navy or its air forces, there were plans to make some sort of strike. The problem was figuring out how to make it that far. To that end, by 1940, Hitler ordered the development of a long-range plane program to produce the Amerikabomber. The initial idea was that it would take off from the Azores, the Atlantic islands held by Germany-friendly Portugal. That went bust when the Allies set up a base there in 1943. German airplane and weapons designers attempted to come up with alternate plans, but nothing ever came to fruition.

Even if this far-fetched plan made its way into reality, it would have only dropped a single bomb — devastating, especially if it hit a densely populated city, but not necessarily a blow that would bring the U.S. to its knees. The postwar chaos that scrambled records makes it all the more difficult to understand what precisely was going on and if anything was ever actually built, though most believe the Messerschmitt Me 264 bomber was a result.

What is likely is that Hitler dreamed of a big, showy strike against a major U.S. city. According to Albert Speer, Nazi Germany's chief architect and minister of war production, Hitler rhapsodically spoke of "skyscrapers being turned into gigantic burning torches, collapsing onto one another, the glow of the exploding city illuminating the dark sky" (via The New York Times).

Mega battleships were in development to face off against the U.S. Navy

While some Nazi developers were puzzling over just how they were supposed to make long-range bombers that could reach New York, others were tasked with developing battleships that could reasonably face the very well-equipped U.S. Navy, perhaps even after making the lengthy journey across the Atlantic Ocean to American waters. Besides the standard complement of regular-sized battleships and aircraft carriers, there were plans to develop what are now known as H-class battleships. These proposed vessels would have exceeded the capabilities of both the U.S. and Japanese battleships that were then in use. The largest was set to be the H-44, a behemoth that would have weighed in at about 140,000 tons and would have sported eight 20-inch guns. If a U.S. warship were to come across a naval monster such as this one, its crew could find themselves in serious danger.

Unlike some of the wilder aircraft proposed by the Germans, we do have evidence that at least a couple of H-class battleships were in production at some point. However, records indicate that neither ever made it to the water. In fact, they were apparently scrapped in the shipyards where they were being constructed, before anyone could even pretend they were battle-ready. Much like the Amerikabomber, the H-class battleships were a failed project that may have only served to waste time and other precious resources in the midst of an already demanding world war.

Economic strikes were on the table

Even in his more fantastical, perhaps even drug-fueled moments, Hitler must have realized that occupying a landmass as large as the U.S. was a major proposition — if not downright impossible. But, if he managed to gain real power over the course of the war, he might be able to strike the U.S. in other ways. Why not hit the Allies right in the wallet?

In a 1941 interview, LIFE reporter John Cudahy raised just that prospect, asking Hitler about a German win wreaking economic havoc on the U.S. Cudahy's notion hinged on his assumption that there was a "lower standard of living for workers in Germany and disciplinary methods imposed upon German labor which would never be accepted in the U.S." Hitler replied that he didn't think living conditions were quite so bad for Germans and that war had interrupted economic progress anyway. Besides, Germany was so comparatively small in both landmass and population that surely it wouldn't be a real threat to the Americans (never mind that whole empire-building thing he had going on).

But Nazi Germany engaged in economic warfare. It took advantage of the economic upset in pre-war Weimar Germany to seize power and turned around the nation's struggling economy (partially via dubious tactics like banning or limiting imports). If it had continued such momentum, anti-U.S. economic retaliation could have been viable. Germany certainly engaged in economic espionage, as when Nazi agents attempted to tank the British economy via counterfeit bills in an attempted mission known as Operation Bernhard.

Hitler likely would have reinforced racist U.S. policies

As much as Hitler and other Nazis officials loudly and publicly criticized the supposed degeneracy of American society, there were some things the U.S. was doing that they admired. Chief amongst them were the nation's racist laws, which served as case studies for Nazis.

In a possible future where the Nazis somehow did manage to take control of the U.S., they would have almost certainly kept these policies and even intensified them. These included racist legislation that shored up segregation, also broadly known as Jim Crow laws. In fact, Jim Crow laws were so notorious that Nazis closely studied U.S. policy when they began socially and legally discriminating against Jewish people and others they had deemed to be "undesirable." For instance, the Nuremberg Laws that legally declared Jewish German people to be non-citizens were directly inspired by American laws, which claimed indigenous people in the mainland U.S. and its territories were also somehow not citizens.

Nazis also took an interest in state-level anti-miscegenation laws that forbade interracial marriages, especially the ones that threatened dire consequences for anyone who married in defiance of such legislation. Nazis simply turned around and implemented it to block marriages between Jewish and non-Jewish people. And to determine just who was Jewish, Nazis once again turned to U.S. policies, though they actually took a step back from the notorious "one-drop rule" that declared anyone who had a hint of Black ancestry was fully, legally a Black American.

There are hints that he would have set off a North American Holocaust

If, somehow, the Nazis had managed to transport enough troops and firepower to the United States to take over the country, and then actually managed to gain long-term control of the nation, they wouldn't have stopped there. Instead, there are hints that they would have continued what proved to be one of their most evil policies: genocide. The information uncovered so far only hints at such activity in both the U.S. and Canada, but it's all too easy to see how it could have become a reality.

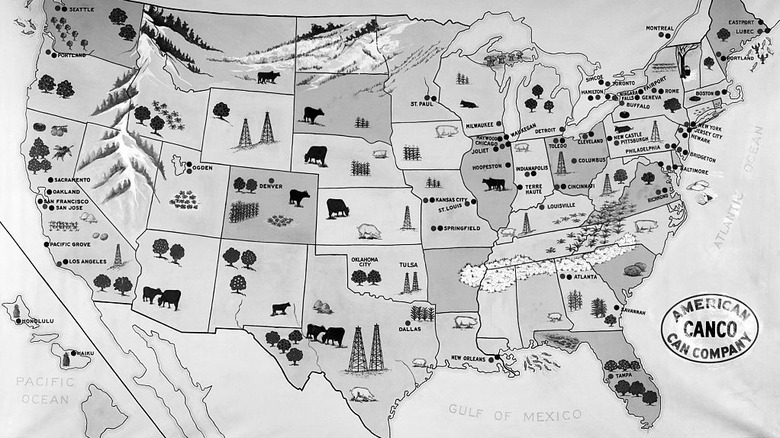

The case centers on a German-language book that is currently held by Library and Archives Canada (LAC). Once owned by Hitler and commissioned by the Nazi Party, its title translates to "Statistics, Press, and Organizations of Jewry in the United States and Canada." It essentially gives a rundown of the Jewish populations in cities both major and minor across the two nations.

To be clear, the document doesn't contain an overt outline for genocide, but it arguably was laying the groundwork for such a thing. The Holocaust as it happened in German-held territory was preceded by this sort of data collection and analysis, making the book in LAC's collection more chilling than it may seem at first glance. As LAC curator Michael Kent told The Guardian, "[The book] demonstrates that the Holocaust wasn't a European event — it was an event that didn't have the opportunity to spread out of Europe."

He at least once expressed hopes of teaming up with Britain against the Americans

Even casual students of WWII can recall that Britain and Germany weren't exactly best friends. The two nations were dramatically opposed, with Nazi Germany sending forth devastating bombing campaigns and blockades against the island nation (and Britain doing plenty to retaliate in turn). So, why did Hitler ever dream of Germany being such great friends with Britain that the two countries could team up against the U.S.?

The answer to that is likely to remain a mystery in many respects. But, excerpts from Hitler's own words and speeches make it clear that he at least hoped Britain — under German control, of course — would prove to be an important resource in a battle against the Americans. By September 1941, he was proclaiming that "I will not live to see it, but I am happy for the German Volk that it will one day witness how Germany and England united will line up against America" (via "Intelligence and Strategy").

He was on much the same track the following year, when he said that "one day England will be obliged to make approaches to the Continent. And it will be a German-British army that will chase the Americans from Iceland" (via "Hitler's Wartime Conversations"). Precisely how he thought that he would convince the British — who had already teamed up with the Americans at this point and weathered the Blitz — to join in on such a venture was never explained.

The U.S. film industry was of great interest to Hitler

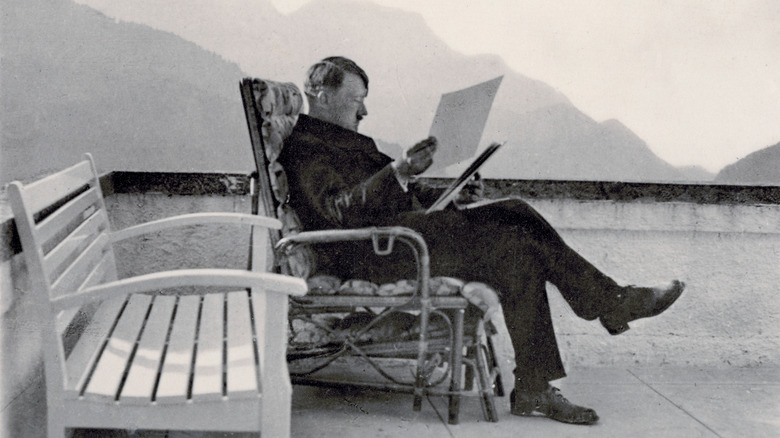

If Hitler were somehow able to achieve a U.S. takeover, the nation's booming film industry would have surely kept going — though in dramatically different fashion. As it stood, Hitler had a particular interest in American movies and understood the power of flashy propaganda films.

In private (and occasionally in public), Hitler was a voracious consumer of film, sometimes watching multiple movies in a night. Those movies might be German, British, French, or even American. He also ordered the production of homegrown movies, like filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl's now-infamous 1935 "Triumph of the Will," depicting a showy Nazi rally at Nuremberg. As much as Hitler might publicly bemoan the supposed state of American culture, he was rather struck by its film industry ... at least, until war broke out. In the 1940s, he became far more interested in newsreels and especially how he came across in them.

Hollywood was friendly to Hitler, too. Sure, you may remember 1942's overtly anti-Nazi "Casablanca," but the true relationship between Tinseltown and Hitler is far more complicated. Business-focused studio executives regularly capitulated to Nazi demands. Researcher Ben Urwand found evidence that studio heads allowed Nazis to edit film scripts, shut out Jewish creators, and perhaps even pushed a German MGM exec to divorce his Jewish wife (via The Hollywood Reporter). Not everyone was on board with these moves, and all the less so once Germany declared war on the U.S. Still, it's not hard to imagine film executives once again bowing to Hitler.

Some prominent Americans would have benefited

In the event of a Nazi takeover of the U.S., a few individuals would have likely thrived. Prime amongst them was Henry Ford, the industrialist who was vocally antisemitic and promoted false theories that Jewish people somehow controlled the world.

Ford was so dedicated to this notion that he purchased The Dearborn Independent newspaper in 1918 and quickly set about publishing these conspiracy ideas in its pages. The Dearborn Independent was conveniently available in Ford Motor dealerships across the nation, while some even found a copy in their newly purchased Ford car. The Nazis gave Ford the "Grand Cross of the German Eagle" in 1938 and Hitler spoke well of him, though the Ford Motor company had a difficult time navigating foreign contracts in a nationalist Germany. There it was called Fordwerke, and it used slave labor in at least one plant from 1941 until 1945.

Famed aviator Charles Lindbergh was wowed by the Nazis; when he toured Germany in the late 1930s, he became a fan of the country's aviation industry and was even given a Luftwaffe medal by Hermann Göring. He refused to return it even as war loomed. But Lindbergh had championed racist ideas and stoked fears of outsiders diluting European American heritage. He was also a vocal proponent of "America First" policies and, in 1941, was photographed giving the Nazi salute at a rally. Privately, he bluntly wrote that America had too many Jewish people. His increasingly public pro-Nazi stance tanked his political career as the U.S. officially entered the war.

The German American Bund and other American Nazi organizations would have likely been ignored

Even as the Nazis engaged in outright war, they still had some support in the U.S. But these groups, including the pro-Nazi German American Bund, were hardly a nefarious fifth column ready to spring into action at Hitler's command. Sure, they dressed like Nazis, marched around like them, created kids' groups similar to the Hitler Youth, and even were part of a 1939 rally at Madison Square Garden that included American flags and George Washington alongside swastikas. But despite some initial interest, actual Nazis and other German officials began to get sniffy about the German American Bund and soon concluded they were fringe oddballs. Even worse, all their goose-stepping, saluting, and speechmaking was only turning American sentiment against Germany.

In the meantime, the U.S. government was busy disabling other avenues of German support. By the middle of 1941, though no declaration of war concerning the U.S. had been made, FDR clearly knew what was coming. His government froze Axis assets under U.S. jurisdiction, shut down German-friendly propaganda operations, and closed all German consulates (with the exception of the embassy in Washington, D.C.). American Nazis even faced prosecution, including Fritz Kuhn, the German American Bund leader who was convicted of larceny and deported to postwar Germany.

The Bund itself faded and was disbanded shortly after the Pearl Harbor attack. Even if it had somehow lingered and existed in the vanishingly unlikely future of a Nazi America, it would have likely been ignored in its pathetically uninfluential state.

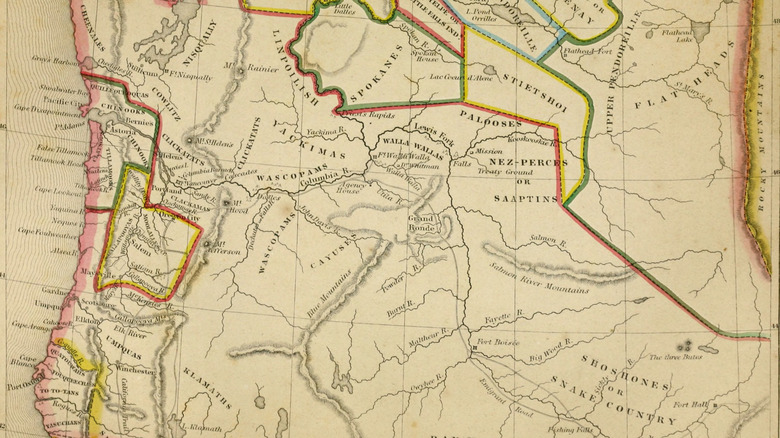

There were notions of inciting indigenous Americans to riot

While Hitler often spoke of the supposed "impurity" of the U.S., there are rumors that Nazis had declared some American Indian tribes to be "Aryan." While that's unconfirmed, it is clear that the German American Bund tried to cozy up to tribes. There are even hints that Germany was, at one point, toying around with the idea of indigenous revolts against unfriendly governments in the Americas. Such rebellions were meant to be in reaction to very real racist policies that marginalized native people.

Though the vast majority of American Indian people rejected the idea of an uprising — including the Native American code talkers who served in the U.S. military — there were occasional exceptions. These included "Chief Red Cloud," actually a lawyer from Portland, Oregon, named Elwood Towner. He was a vocal advocate for indigenous rights but, somewhere along the way, had decided that Jewish people were behind many of the problems he fought against. He aligned himself with the Nazis and the German American Bund, and occasionally spoke of a deep connection he felt with Hitler.

Another group associated with Towner, the American Indian Federation (AIF), was led by Creek man Joseph Bruner. Like Towner, he opposed many laws and policies limiting the rights of American Indians and, in so doing, arguably aligned his group with fascism (at least in the eyes of investigators) in its quest to oppose Communism and encourage assimilation. Another AIF member, Seneca activist Alice Lee Jemison, even accepted fundraising support from Nazi-linked individuals and organizations.

It's not clear that he ever seriously planned for an occupation

Ultimately, though there are bits and pieces of evidence that suggest Hitler eyed the U.S. as potential territory, there's little concrete information outlining a plan to occupy the country. There are hints, from the development of long-range bombers to widespread American assumptions that he would try his hand at a bit of world domination (a poll conducted by Fortune in 1941 found that 72% of respondents in America thought that was Hitler's end game).

But was there a plan? A blueprint? Heck, was there even an outline hastily sketched out on a napkin or in the back of a notebook? No, not as far as anyone could tell. Going by the overall shape of Hitler's strategy, his fanatical obsession with purity and power, and the way in which he seemed dead-set on achieving his goals to the detriment of practical war concerns like, say, supply lines, there's plenty of circumstantial evidence to suggest the U.S. would have come in his sights eventually. But, in that environment of fanaticism and head-spinning propaganda — and despite all those meetings where Hitler was pictured standing over maps and surrounded by officers — an actual, concrete plan for occupying the United States may have been the most far-fetched thing of all.