Things About The Iraq War That Don't Make Sense

The Iraq War lasted for nearly nine grueling years and cost the lives of thousands of American and allied troops, as well as hundreds of thousands of Iraqis, mostly civilians. Including the interest on debt incurred to finance the war and medical care for injured veterans, the purely economic price tag creeps into the low trillions.

The war was criticized even before it began, with many Americans joined by people abroad in protesting the George W. Bush administration's plans to invade. As the conflict continued and the human, cultural, and financial tolls skyrocketed, more and more people asked why the United States had involved itself, what the plan was, and if the country had learned nothing from its long and unsuccessful interventions in Vietnam and its neighbors. A decade-plus after the U.S. military withdrawal in December, 2011, various aspects of the conflict, its planning, and its legacy still don't make much sense.

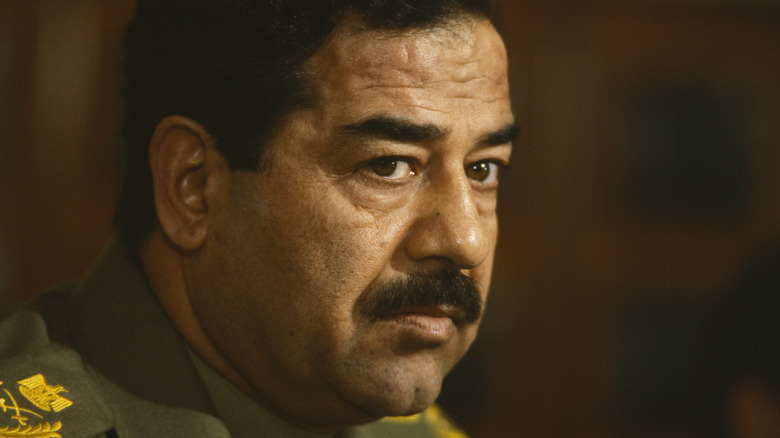

Why was Saddam Hussein left in power?

Saddam Hussein was, by any credible account, a very bad man. He was guilty of wars of aggression, genocide, chemical warfare, and possibly the bewildering blasphemy of having a copy of the Quran written in Hussein's own blood. But he'd also been roundly defeated by a colossal alliance of world powers after his 1990 invasion and attempted annexation of neighboring Kuwait. If Hussein and his forces had been on the ropes in 1991, why hadn't this force deposed him or done something even more decisive?

The answer seems to be that beating the Iraqi army in battle in the country's south and driving it out of Kuwait was a much smaller undertaking than a full-scale invasion of Iraq would have been. Iraq is not a small country, and Baghdad is toward the center, so an invasion force might have had a long and hotly contested route ahead of them.

The appetite for "regime change" was also simply not there for many of the assembled allies. The brief was to liberate Kuwait and bloody Iraq's nose, not "fix" Iraq, and the United States might have found itself fighting alone if it had gone for the stretch goal of a dead Saddam Hussein. And in 1991, as in 2003, the question would still remain: What next? Hussein was terrible, even many of his own people agreed, but there was no clear "good guy" to set up in Baghdad. Desert Storm set specific goals, attained them, and avoided mission creep — a lesson that was lost in the 12 years before the next time a U.S.-led coalition was in Iraq.

Where were the weapons of mass destruction?

It was the grimmest Easter egg hunt on record: Where were Iraq's weapons of mass destruction? A key part of selling the war to skeptical segments of the U.S. and, in particular, British public had been the argument that the Hussein government was stockpiling chemical, biological, and/or nuclear weapons, and the threat had to be neutralized before these weapons were turned against Iraq's enemies, real or imagined, internal or external. But when the boots hit the ground, searches for these arsenals came up short.

The simplest explanation, if also most self-serving for the allies, is that Iraq tossed the weapons like so many hot potatoes into friendly Syria before or in the early stages of the war. Hussein had used poison gas against civilians before, killing Kurds in the country's north to try to smash their drive for independence or autonomy. It's not like WMDs were somehow beneath him, but there was no clear evidence of their transfer out of Iraq.

Another possible explanation is that factions in the United States and British governments had decided on the war and cherry-picked evidence to support the presence of WMDs, building the case to the public out of scraps instead of the whole picture. Additionally, spies reporting to U.S. and U.K. intelligence may have had their own agendas, polishing or manufacturing reports of WMD development to bring the hammer of American might down on Saddam Hussein.

Why was an al-Qaeda connection imagined before one existed?

Among the reasons presented by the George W. Bush administration for the invasion of Iraq was an alleged operational alliance between the Iraqi government and the terrorist organization al-Qaeda, a cooperation allegedly going back to the early 1990s. But after the invasion, even a U.S. congressional report acknowledged that no proof of such close ties between the two organizations could be found: Whatever Saddam Hussein's sins may have been, buddying up with al-Qaeda was not among them.

It was, in a sour irony, the chaos uncorked by the allied invasion that allowed al-Qaeda to begin operating in Iraqi territory. Al-Qaeda (correctly) identified the American-led war effort in Iraq as an opportunity, and distributed a guide to guerrilla warfare to both Iraqis and foreigners interested in throwing sand in the machinery of the occupation. After the overthrow of the Hussein government, an al-Qaeda franchise began operating in Iraq, targeting Shia Muslims and their holy sites through terror campaigns as well as security forces and civilians regardless of religion. Once it began to occupy territory, al-Qaeda in Iraq rebranded itself as the Islamic State, terrorizing Iraqis and Syrians in its usurped territory and inspiring attacks in Europe and North America.

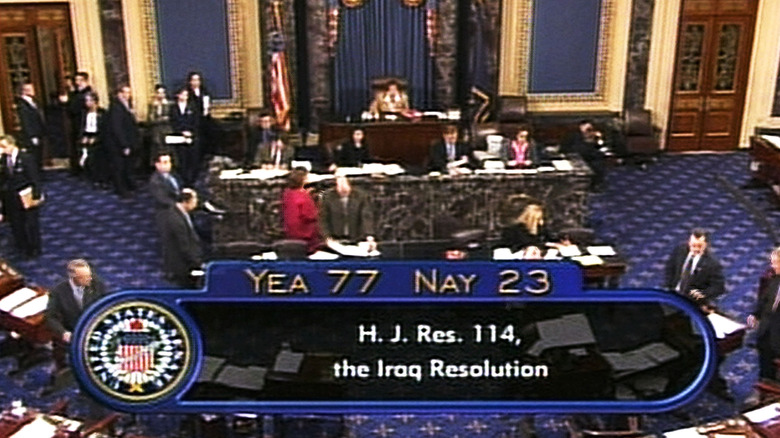

Why was war not formally declared?

The last time the United States Senate formally declared war was June 4, 1942, a three-fer against minor Axis powers Bulgaria, Hungary, and Romania. You might notice that the United States has fought North Korea and China, Vietnam and its neighbors, Afghanistan and Iraq twice, and even American neighbors like Panama and Grenada since then, among others, but these weren't, in the very strictest definition, wars. Instead, Congress uses "authorizations of military force" or allows itself to be bypassed altogether.

Harry S. Truman realized he could circumvent a potential congressional refusal to declare war in Korea by committing American troops to a U.N. force. Presidents since then have found other ways to work around Congress' war-making authority, and Congress has generally been willing to let them. If you declare war, you're responsible for the outcome, but a mere kinetic action or limited engagement can be positioned to voters as something less than war.

A 1973 "War Powers Act" reacted to Vietnam, somewhat retroactively, by theoretically forcing presidents to notify Congress within 48 hours of the use of force abroad (by which point most of them would have read the news), and limiting unilateral presidential uses of force to "only" 60 days without congressional approval. Legal complaints that presidents have flouted this act are, however, usually dismissed.

Who okayed the mission accomplished photo op?

On May 1, 2003, President George W. Bush gave a televised victory address aboard the nuclear-powered aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln. In the limited defense of the president and his communications team, it wasn't their idea for the address to take place in front of a big banner that read "Mission Accomplished" — that idea came from the Abraham Lincoln's crew, who had adopted the phrase as an unofficial slogan after a long deployment at sea.

Bush's idea or no, "Mission Accomplished" became the takeaway idea from the speech. In just a few weeks, the Iraqi givernment had been ousted, and only 140 American servicemembers had died in the operation so far. Briefly, the mission did seem to have been accomplished, but the security gains from the rapid conquest eroded nearly as quickly. Neither U.S. and coalition forces nor the Iraqi public had faced anything close to the worst the war had to give.

When the violence escalated, the "Mission Accomplished" banner, along with images from the same address of Bush in a flight suit in a fighter plane cockpit, came to seem naive at best. Civilians and American soldiers continued to die, at escalating rates, and the war's harshest critics came to argue that nothing lasting was ever accomplished.

Why was Poland such a major participant?

In March 2003, the United States publicized a list of the "Coalition of the Willing," its allies in the invasion of Iraq. 31 countries were on board, though commitments varied. A number of countries limited their involvement to "public support," a famously low-risk contribution, and others offered only token help. In among the single Danish submarine and the right to fly over Bulgaria, however, was a comparatively whopping 1,500-man personnel commitment from Poland. At the height of its involvement, Poland had 2,500 peacekeeping troops in Iraq and oversaw a coalition of smaller deployments from other countries, with operational command over five Iraqi provinces. Polish forces remained until 2008, and 28 Polish troops died.

Why was Warsaw so eager, especially when the Polish public at large took a dim view of the upcoming conflict? The Polish government, relatively recently freed from the Warsaw Pact with the late Soviet Union, saw the war as an opportunity to cuddle up to the United States and present itself as an independent actor on the world stage, its time as a Russian satellite well and truly over. Poland had joined NATO in 1999, and riding along on the invasion of Iraq presented another step in refashioning its reputation into that of a Western, U.S.-aligned power. (And though they didn't actually materialize, the promise of Polish firms reaping reconstruction contracts didn't hurt either.)

Why weren't antiquities protected?

Iraq's position in the Fertile Crescent, which nurtured many premodern civilizations, means that the country is heir to some astonishing antiquities. As the home of the sites of ancient cities like Babylon, Nineveh, and Ur, modern Iraq is one of the most archaeologically important states in the world. Securing these sites and artifacts should have been an important factor in invasion and occupation planning, both because of their importance to Iraq and the world, and because movable antiquities are big-ticket items that can be resold to unscrupulous collectors, with the money potentially funding insurgency.

That responsibility to care for Iraq's cultural heritage was badly bungled by the occupation authorities. Not only was the Iraq National Museum in Baghdad looted, but field sites across the country fell prey to illegal and destructive excavation. Further sites and artifacts were deliberately destroyed by the brutally iconoclastic Islamic State during their heyday in the country's north. Looted antiquities have been traced to various countries in Europe, North America, and the Middle East, with repatriations from the United States alone reaching 17,000 items, including an early clay tablet copy of the Epic of Gilgamesh. Over 40,000 more artifacts are awaiting return or are actively sought by Iraqi authorities in cooperation with the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

Why was de-baathification mismanaged?

The apparatus through which Saddam Hussein kept his vicious grip on the Iraqi state was the Baath party, a political organization that proposed generally socialist development, a single Arab state, and tight, top-down control. After the fall of Hussein's government, one priority of the occupation forces was the "de-Baathification" of the country, firing Baath party members from positions of public trust and dismantling the party organization beyond repair.

Some level of de-Baathification was probably necessary, but the U.S.-led coalition took too many shortcuts in figuring out how to carry it out. Everyone who was anyone in Hussein's Iraq had to join the Baath party, and so occupation authorities dismissed all of those people instead of going through the tedious but more precise process of inquiry into individuals' complicity with the regime and its crimes. (For reference, this wholesale firing is arguably harsher than the de-Nazification of Germany was.)

This political cleansing might have felt good, but with everyone who used to run the country booted from office, no one was left to run the country. School staff and education administrations were hollowed out, the state was unable to carry out some of its basic functions, and people who had grudgingly gone along with the Hussein regime felt ill-used by the new authorities. Oh, and the entire Iraqi Army was disbanded, flooding the country with angry, unemployed men with combat experience in a move that predictably worsened the security outlook.

Why do death toll estimates vary so widely?

It's a straightforward question, even if it's not an easy one to answer: How many people died in Iraq as a result of the war? The question is difficult to answer definitively not just because of the inherent chaos of war, but because to answer it, researchers need to define what it means "to have died because of the war." While initially this may sound like government-style semantic hair-splitting, the actual definition of a war death is variable depending on methodology and the choices made by individual organizations tracking the violence.

The nonprofit Iraq Body Count gives a range of 187,499 to 211,046 civilian deaths specifically from violence, excluding both military personnel and people who died because of secondary factors like displacement or illness. The range is given because the organization acknowledges that, again given the disorder, some reports may be inaccurate, missing, or double-counting deaths. A different 2013 study estimated 461,000 dead based on household surveys, but included people who had not died directly from violence. Given the failure of state functions and medical systems, as well as stress, this study includes some deaths from illness, and estimates that some deaths among people who had fled Iraq could be assigned to the war's total.

An even more pessimistic project by Brown University attempts to tally the total dead of indirect and direct causes in all post-9/11 U.S.-led wars. This estimate stands at over 4.5 million deaths from all causes; a number that continues to rise.

Why was the occupation force relatively small?

Iraq is about the same size as California, and in 2003 was home to just under 27 million people, a few million more than Texas had at the time. Given the size of the country and the number of people who needed to be controlled, why was the invasion force a relatively small 145,000 American troops, bolstered by a few thousand from allied forces?

Even when the occupation force numbers were boosted in 2007, deployed U.S. forces topped out at 170,300. For comparison's sake, the U.S. deployed 300,000 troops to fight in the Korean War, with nearly 1,800,000 Americans serving in the Korean theater in some form, and 2.7 million over the course of the war to Vietnam, which infamously did not seem to be enough.

The small force was, in fact, a selling point. The Army chief of staff at the time of the invasion, General Eric Shinseki, had stated to Congress that hundreds of thousands of soldiers would be needed to fully secure Iraq. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld and his political allies brushed these concerns aside, focusing on the alleged "cakewalk" that awaited American troops on the road to Baghdad. Rumsfeld and others were ostensibly reforming the U.S. Army into a nimbler, leaner fighting machine, and success in Iraq was expected to prove the wisdom of this approach — but when it came time to hold what they'd taken, this lean force was short of muscle.

Why wasn't a clearer plan for Iraq's future in place?

"And then what?" could serve as the epitaph for the American involvement in Iraq. The initial invasion was successful by any standard, and then the subsequent occupation and ostensible rebuilding phase turned into a bloody and expensive slog whose endgame remained unclear. Why was a military power like the United States capable of toppling the Iraqi government so quickly, but unable to prepare for the day after?

The answer seems to be simple optimism. Key figures in the administration, Donald Rumsfeld among them, expected the war to go well, and so they planned for best-case scenarios, sending in a relatively small force. Additionally, American military planners simply do not seem to have made a concrete plan for the subsequent occupation, particularly for the critical task of maintaining security. Iraq's government was to be swept from the board, its army disbanded, and then, somehow, something would happen. Maybe one of Hussein's generals would take over, or perhaps Ahmed Chalabi, an influential Iraqi exile who had lobbied for the U.S. invasion.

The failure to plan would prove even more damaging to American efforts than it initially seemed. Estimates placed the Iraqi resistance at only about 5,000 fighters in mid-2023. A year later, the figure had ballooned to an estimated 20,000, swollen by people who found themselves with their options limited by the security situation. Frustrated by the chaos, they joined it.