Why The US Navy Shot Down A Passenger Jet

On July 3, 1988, during the waning days of the Iran-Iraq war, the U.S. Navy cruiser Vincennes was patrolling the Persian Gulf to protect shipping when it fired on an Iranian aircraft. As immediately became clear, the plane that the Vincennes had shot down was not a military craft, but instead a civilian airliner. Iran Air Flight 655 was on a short hop to Dubai when it was struck, killing all 290 passengers and crew aboard.

Predictably, the incident further soured the already-poor relations between the United States and Iran, with the Iranian government claiming the strike was a deliberate massacre of civilians. Internal U.S. investigations did not concur, though the Navy did come under significant public criticism. Why had a targeting system as allegedly sophisticated as that aboard the Vincennes made such a grievous and credibility-cracking error? Publicly available information implies fault on all sides — the Iranian armed forces, the crew of the Vincennes, the pilot of the doomed airliner — and underscores the dangers that wartime confusion and hasty decision-making can pose even to noncombatants. To fully understand why the USS Vincennes downed Iran Air Flight 655 requires an understanding of the tragic chain of events that led to the event, and the context within which it occurred.

Tensions had been high between Iran and Iraq for decades

By mid-1988, tensions had been high between Iran and Iraq for decades. The Shatt al-Arab — a short river formed by the joining of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers that flow through Iraq — forms part of the Iran-Iraq border. The Shatt al-Arab is Iraq's only direct connection to the sea, but it's also an important waterway for Iranian commerce, and the states of this dry part of the Middle East have intermittently fought over the water in this river system for millennia. Iran and Iraq had squabbled over the exact border and sovereignty delimitations regarding the river for decades before war began in 1980, and Iran had been supporting Kurdish separatists in Iraq's north to weaken its rival, trying to force Iraq to "negotiate" and recognize shared Iranian control of the Shatt al-Arab.

This wasn't the only territorial dispute. Iran had helped itself to some small, contested islands in the Persian Gulf in 1971, and Iraq coveted the oil-rich Khuzestan province of Iran across the Shatt al-Arab. When Iran's emperor was booted in 1979 by the Islamic Revolution, Iraq worried that the new, militant Shia government in Iran would agitate the Shia minority in Iraq's east and noticed that Iran's military was not as prepared for a fight as usual. (Saddam Hussein and Ayatollah Khomeini also apparently hated each other personally, an animus dating from Khomeini's expulsion from exile in Iraq.) Saddam Hussein saw an opportunity — and took it.

War broke out in 1980 and lasted for eight years

On September 22, 1980, Iraqi forces invaded Iran across the countries' shared border, hoping to seize Khuzestan; they soon got bogged down under fierce resistance from the Iranian Revolutionary Guards, which had been formed as an internal militia after the revolution but was surprisingly competent to defend against an invader. By 1982, the Iranians had compelled the Iraqis to withdraw and Iraq offered a peace settlement, but Ayatollah Khomeini's hackles were up, and he ordered his forces to continue the war in hopes of ousting Saddam Hussein.

The remaining six years of the war were a slow-motion bloodbath, with Iran taking the worst of it. The front settled more or less at the pre-war border, and human wave attacks by Iranian forces failed to punch through. The combatants turned to attacking each other's shipping and bombing each other's cities. Late in the war, Iran tried to work with the Kurds, an ethnic and linguistic minority who live in northern Iraq and the surrounding territories. Kurdish forces cooperated with an Iranian advance in Iraq's north, giving the Hussein government an excuse to attack Iraq's Kurds with chemical weapons in a series of genocidal pogroms.

By the summer of 1988, total casualties stood at one to two million. Neither side had much to show for the years of war, and a ceasefire came into force on August 20, 1988.

Foreign countries involved themselves

While the actual combat of the Iran-Iraq war generally stayed within Iran and Iraq, third-party states lined up to try to help their favored fighter win, and some of the alliances make for strange reading for a modern audience. Iraq could count on financing and diplomatic support from a number of other Arab states, particularly deep-pocketed Saudi Arabia and future victim of the Gulf War, Kuwait. The United States and Soviet Union, usually rivals, both quietly preferred an Iraqi victory: the U.S. to see the anti-American regime in Iran defeated, and the Soviets apparently because they thought the Hussein regime might eventually flower into a socialist Iraq.

Iran had fewer open backers given the untested nature of its new government, but one regional heavyweight stood out: Israel. Before the long-running Iranian-Israeli hostility had really blossomed, Israel covertly supported the Iranians against Iraq, hoping to hobble the Arab power and ease the emigration of Iranian Jews who wished to leave for Israel or the United States.

In 1984, Iran and Iraq begin attacking each other's oil shipments

Iraq had been targeting Iranian shipping since early in the war, but in 1984, with the land front between Iran and Iraq at an impasse, both Iran and Iraq realized something had to give. Both belligerents upped their assaults on one another's shipping in what became known as the Tanker War. Oil transport ships were the most important but not the only targets, as both sides attacked the other's ability to sell products (most profitably, of course, petroleum) and import resources.

Iraq had better missiles, at least at first, benefitting from supplies of French weapons. This onslaught of Exocet missiles forced Iran to attack more creatively, using smaller weapons meant for land use. These were generally unable to sink large ships, but could cause deaths and injuries to crews if cabins were effectively targeted. And all this was going down in the busy waterways of the Persian Gulf and the Strait of Hormuz, a key artery for the global oil trade. Despite everyone's efforts, the chaos didn't even raise the price of oil: Iran lowered its prices to compensate for rising insurance rates, and global oil prices never saw a lasting spike during the conflict.

Iran went on to attack shipping in general, leading to a US warship hitting a mine

China provided Iran with some Silkworm missiles in early 1987, which despite their soft name meant Iranian forces could subsequently pose a significantly more formidable threat to shipping. Iran could also now expand its strategy: Instead of simply badgering shipping and killing the odd sailor, the Islamic Republic could retaliate against Iraq's trading partners and financial sponsors. That they did, causing theoretically neutral Kuwait to appeal to the Western powers, particularly the U.S., to defend shipping in the Persian Gulf.

The United States agreed to place Kuwaiti oil tankers under the U.S. flag, meaning that they were then eligible for protection from U.S. Navy ships. The Navy deployed a force to carry out this armed switcheroo in early 1987, which is why the USS Samuel B. Roberts was in the Persian Gulf on April 14, 1988. It had been warned of Iranian-set mines in the water, but struck one anyway, with the explosion tearing open a 21-foot hole in the ship. All hands survived, but 10 on board were injured, and the ship limped to Dubai for emergency repairs.

The United States responded with Operation Praying Mantis

Incensed at the damage to the USS Samuel B. Roberts, the United States responded on April 18, 1988, with a punitive attack called Operation Praying Mantis. Over the course of that single day, the United States retaliated against Iranian forces in the largest surface-based combat the U.S. had seen since Japan's surrender in World War II.

American forces destroyed two Iranian oil platforms that had been used for surveillance support, with a detachment of Marines spending two hours scoping one of them for information before the final explosion was set. Three Iranian warships had also been sunk, and their most notorious, the Salaban, crippled and puttering meekly back to port. At the price of only two lost pilots, along with the helicopter they had been in, the United States had bloodied Iran's nose and was prepared to increase its involvement. Shortly after Praying Mantis, the United States announced it would protect all neutral shipping in the Persian Gulf — indicating an indefinite U.S. naval presence.

US and Iranian craft had been scrapping the morning of the incident

By the time of the tragic events of July 3, 1988, Iran's naval capacities had been degraded by the success of Operation Praying Mantis, but the Islamic Republic was not out of the fight. The Revolutionary Guard had its own naval arm, which had taken less damage than the regular Iranian navy, and this Revolutionary Guard waterborne force returned to badgering shipping in the Persian Gulf over the course of May. Iraq was still carrying out attacks on Iranian territory, and Iran was still convinced that cutting off trade would stop or slow Iraq's ability to make war.

On July 2, an American ship scared off some Iranian boats attacking a Danish tanker. On July 3, more Revolutionary Guard boats threatened a Pakistani ship, then fired a machine gun at an American helicopter sent to investigate. In the course of this interaction, the USS Vincennes left its assigned station without orders and crossed into Iranian territorial waters. When the Iranian ships turned to face the approaching Vincennes and another U.S. ship, the Elmer Montgomery, the Vincennes fired and sank two of the Iranian ships.

A civilian Iran Air flight was hit by missiles from the USS Vincennes and crashed with all lives lost

Minutes after the Vincennes had sunk the Iranian boats, Iran Air flight 655 took off from Bandar Abbas airport on Iran's southern coast, planning a short 30-minute flight across the Strait of Hormuz to Dubai. Its flight path took it almost directly over the small naval battle unfolding between the American and Revolutionary Guard ships.

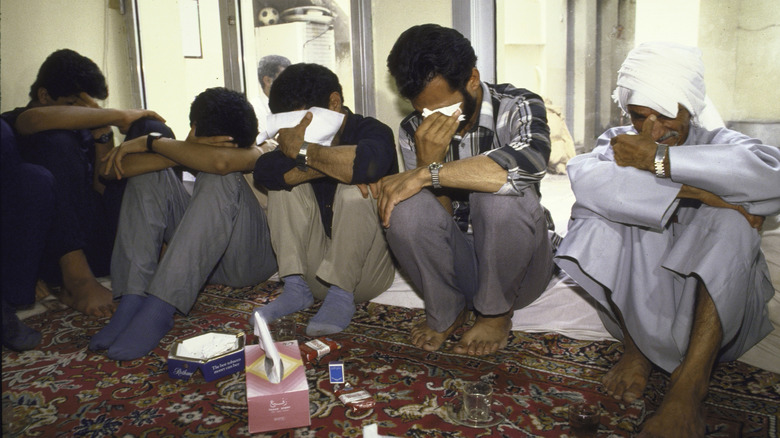

While Iran Air 655 was still in Iranian airspace, the USS Vincennes fired two surface-to-air missiles at the airliner, hitting it in the wing and the tail. The airplane broke up, killing all 290 passengers and crew on board, some of whose bodies were visible as they came free from the shattered aircraft and fell into the waters below. Once it became clear what had happened, the Revolutionary Guard ships were ordered to begin a search and rescue operation, but no one had survived the plane's destruction.

A perfect storm of confusion

Iran Air 655 had found itself the victim of a perfect storm of circumstances, a pileup of chance and human error resulting in a catastrophic miscalculation. While the U.S. ships defending shipping in the Gulf had manifests of planned air traffic, and Iran Air Flight 655 was in both Iranian airspace and one of the established civilian corridors, the flight took off about 30 minutes late, meaning that for someone without this last piece of information, there was a plane where no civilian craft was expected. Four time zones were in use in the area, which didn't help, and Bandar Abbas Airport was a mixed civilian-military facility, so it wasn't irrational to think an attacking craft could come from that site.

The captain of the Vincennes, William C. Rogers, was known as an aggressive leader eager for a fight, as evidenced by his crossing into Iranian waters without authorization from higher-ups. At the time of the attack, the Vincennes had just executed a turn so sharp that objects scattered all over the bridge. Lights were flashing inside the ship as it fired, and so it was difficult to think or read information clearly — as the crew would soon realize.

The crew of the Vincennes had been told to react to an incoming attack craft

Shortly after Iran Air 655's takeoff, the Vincennes's radar system identified both the airliner and an Iranian F-14 fighter jet on the ground. Someone on board the Vincennes, who was never identified, apparently got them confused and labeled the passenger liner as the F-14. Another American ship got this faulty info from the Vincennes and locked onto the plane, but realized from the plane's flight path that it must be a civilian craft. No one aboard the Vincennes made the same realization, nor did they ask for clarification from any of the American F-14s flying in the area.

Meanwhile, the Aegis targeting system on board the Vincennes was so new and complex that most of the crew didn't really know how to use it yet. It was impressive, being able to track and respond to 200 simultaneous potential threats automatically, subject to crew override. But that doesn't matter if one of the officers doesn't use it and just puts sticky notes on the radar screen, as the Vincennes' surface tactical warfare officer did at that time.

Worsening the situation, Iranian military craft sometimes used civilian friend-or-foe radar signals, so the commercial signal coming from the airliner did not prove it was a civilian craft. But even if the airliner had been an attack jet, a single F-14 would have posed little danger to a ship the size and strength of the Vincennes.

The Iranian pilot did not respond to hails, despite being in contact in English with air traffic control

Some questions arose about Moshe Rezaian, the pilot of Iran Air 655. An experienced pilot who often flew the Bandar Abbas-to-Dubai route, he did not do anything wrong: He was in the designated civilian corridor, transmitting the right frequency, and ascending on a flight path that should have been unremarkable. But had he missed an opportunity to identify his craft clearly to the American warships below?

Rezaian had a lot to do on a short flight, and he was in contact with air traffic control in Bandar Abbas and Dubai during the fatal journey. Those exchanges were also in English, so no language barrier would have been the issue. He couldn't have known about the scuffle happening in the water below him, but an alert had gone out months before to all pilots operating in the area, advising them to monitor air distress frequencies and be prepared to identify themselves. The Vincennes did send out requests for identification, but Rezaian either didn't hear them or reasonably assumed they weren't directed at him, as he was on an established, published itinerary.

No US sailors or officers were punished, but they were criticized in the media

In the aftermath of the downing of Iran Air 655, the Iranian public was unsurprisingly furious, with many convinced the United States had intentionally shot down the civilian craft, along with some who feared the attack meant the U.S. was entering the war openly on the side of Iraq. This fear, and the shocking civilian toll in a single incident, are cited as among the reasons Iran agreed to end the war in August 1988.

The American public was also critical, in part because military spokespeople had lied in their initial report of the event, describing the doomed airliner as descending at the time of the shooting, operating outside the established flight route, and over international waters, all of which were false. Photographers embedded with the crew of the Vincennes captured fist-pumping celebrations after the target was hit but before the mistake was realized, which created the impression of a locker-room free-for-all. And wasn't this Aegis system supposed to be foolproof?

A post-mortem investigation by Rear Admiral William Fogarty was scrubbed for public release, though most details eventually came out, revealing the Vincennes's off-book actions. Nevertheless, no one who had been aboard the Vincennes was disciplined, and many later received medals, including Captain Rogers.

The US paid a settlement without admitting fault in 1996

The position of the United States was and remains that the incident was regrettable but not unreasonable: Captain Rogers and the crew of the Vincennes made a rational decision based on the information they had during the heat of battle. As such, the United States has never admitted fault in the shooting down of Iran Air 655.

Iran brought the United States to the International Court of Justice over the incident in May 1989, and after years of negotiation, a settlement between the countries was reached in February 1996. The United States agreed to pay Iran $131,000,000 in compensation, of which just under half was to be split among the estates and heirs of the individuals killed, with the rest going to the Iranian government. This settlement, complete with a brief and carefully calibrated acknowledgment of "deep regret" (via the International Court of Justice), brought the legal dimension of the incident to a close.