Haunting Cold Cases Solved By Genetic Genealogy In 2025

Police in general and hyper-skilled detectives specifically have been tracking down criminals for hundreds of years with a variety of tools at their disposal. Only relatively recently have crimefighting and victim identification grown into a sophisticated science, and that's because of a few watershed moments, such as the evolution of fingerprint technology, the emergence of DNA testing of evidence, and genetic genealogy.

A great many cold cases have been solved because of genetic genealogy testing. Newly discovered or older evidence, including human remains, can be scientifically tested, and the data garnered is run through DNA databases to which people have willingly contributed. Previously and perpetually unidentified murder victims or people found deceased can be identified from their genetic similarities to cataloged individuals. Genealogy testing and analysis can provide infallible clues to who a person was, and it can solve long-open and mysterious cases and provide closure to relatives. In recent years, some of the saddest, longest outstanding, and altogether haunting mysteries have been solved through the power of genetic genealogy testing. Here are some cases put to rest in 2025 alone.

The Middle Child of Bear Brook State Park

A grisly and tragic discovery was made in New Hampshire's Bear Brook State Park near Allentown in 1985: The bodies of a woman and a girl were uncovered in a barrel. In 2000, another barrel with two more unidentified girls, most likely murdered, was found close to where the first barrel was found. By 2019, after connecting the deaths to serial killer Terry Rasmussen, three of the four sets of remains had been conclusively identified as those of a former partner of Rasmussen and her daughters: Marlyse Honeychurch, Sarah McWaters, and Marie Vaughn, respectively.

Called "The Middle Child" by law enforcement and the media, the identity of the fourth and final Rasmussen victim from Bear Brook State Park was revealed in September 2025. Her name was Rea Rasmussen, and she was about 9 years old when she died. A company called Firebird Forensics, along with the DNA Doe Project, analyzed genetic structures and conducted DNA analysis, and linked the remains to one of Rasmussen's kidnapping victims. Using hair samples, scientists were able to link Rea Rasmussen's DNA to that of the deceased Terry Rasmussen, who was her biological father.

'Sheila' of Nashville

In 1987, a woman living in a home on Charlotte Avenue in Nashville found the remains of two women who had degraded to only skeletons in the dirt beneath a crawl space. Nashville police quickly connected the case to James Shaffer, at the time imprisoned in Kentucky for the kidnapping and assault of a teenager. He'd lived in the home in question in 1985 and had confessed to a double murder of two sex workers he knew by the names of Sheila and Little Bit. At the time, authorities were unable to pinpoint the identities of the murder victims.

The Metropolitan Nashville Police Department finally figured out the actual identity of one of Shaffer's victims in 2025. Sheila turned out to be Sheila Cummings, a 23-year-old native of Elgin, Illinois, who'd been reported missing in 1984. The MNPD's Cold Case Unit reopened the case after Cummings' daughter reached out after reading about the mystery on the internet, and thought her mother might be the woman known only as Sheila. Utilizing DNA testing and genetic records, police were able to scientifically connect one of the victims to her relatives. Little Bit's real name and background are yet to be determined.

John Lorton Doe

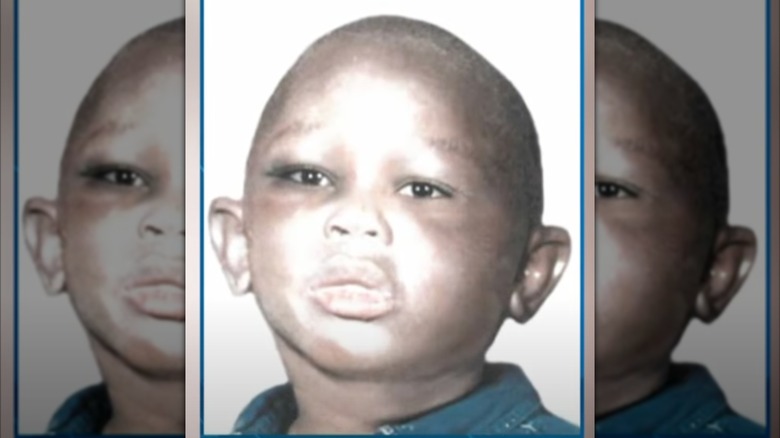

The small body of a child was discovered in a Fairfax County, Virginia, creek in June 1972. At the time, investigators could determine that the individual had died as a result of a blunt force trauma event no more than a day before the discovery. And that was all detectives could determine about the murder victim, whose death became a cold case filed under the placeholder name John Lorton Doe for more than five decades.

Rapidly developing criminological technology in the 2000s provided more clues and information about the remains, the manner in which they died, and who they were. In 2004, facial recognition software led to a notion of the boy's appearance when he was alive, and the FBI was able to create a DNA profile based on a few hairs used in the 1972 autopsy. Still, the case remained open until 2021, when the final traces of testable hair were sent to a forensic lab for sophisticated testing. The information gathered from that was used to build a genetic profile, which was compared to samples in genetic databases. In 2025, the Fairfax County Police Department announced that John Lorton Doe was really Carl Matthew Bryant, and he was 4 years old when he died. His DNA was a match to his mother, Vera Bryant, who died in 1980, and was exhumed in an effort to make the match.

According to Vera's family, Vera and her boyfriend, James Hedgepeth (also deceased), said they were going to Virginia with Carl and his infant brother, James, to visit Hedgepeth's family, but she came back without the children, and they never saw them again. Baby James' whereabouts are unknown.

A body discovered in Lee County, Arkansas

In a field off of Highway 79 in Lee County, Arkansas, in January 1977, the remains of an adult male were discovered. They had decomposed to the point where little more than a skeleton remained intact, and the Arkansas State Crime Laboratory Medical Examiner's Office could determine almost nothing from their tests, including the cause of death and the identity of the person.

Decades later, the Arkansas State Police's Cold Case Unit opted to take another look at the case to see if modern tech could be used to generate any new information or leads. The still unidentified remains went to Texas-based DNA testing firm Othram Labs in March 2024, and in June 2025, the agency delivered its report. After analyzing genetic patterns and comparing them to documented genetic records, Othram determined that the man who died in 1977 was Charles Howard Wallace, 21 at the time of his death. He'd left his hometown of Memphis three years earlier and lost contact with his family; the manner by which Wallace died is yet to be conclusively figured out.

The Yogurt Shop Murders

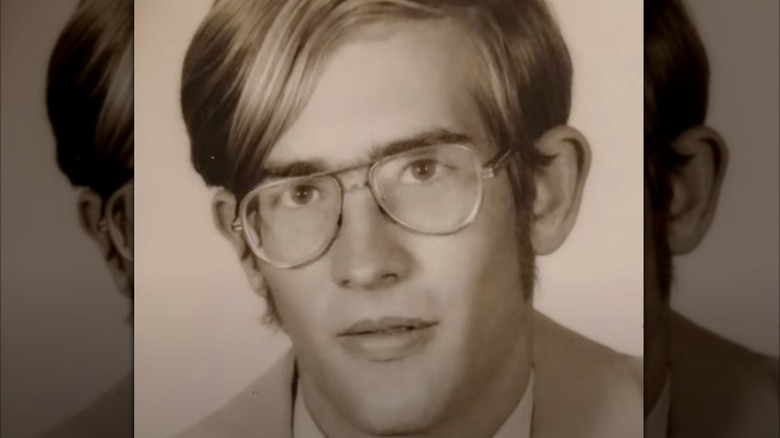

In 1991, a yogurt shop in Austin, Texas, was discovered ablaze, but when emergency responders arrived to douse the flames, they found a heartbreaking surprise — or four of them. Inside the I Can't Believe It's Yogurt! shop, they discovered the bodies of Amy Ayers, Sarah Harbison, Jennifer Harbison, Eliza Thomas, who ranged in ages from 13 to 17.

In the decades since, experts had tried — and failed — to find who was responsible for the murders. While there were some arrests and incarcerations over the intervening years, later investigations exonerated those imprisoned. In the '90s, technology wasn't what it is today, but investigators retained evidence in hopes that in the future, tech could help solve the case.

And that's exactly what happened. In late September 2025, authorities announced that DNA and ballistic evidence had, at last, unearthed a suspect — serial killer Robert Eugene Brashers. "The overwhelming evidence points to the guilt of one man and the innocence of four," said Travis County District Attorney Jose Garza (via KXAN).

While the girls' families finally have closure, there will be no arrest in the upcoming days — Brashers died by suicide in 1999.