Historical Figures You May Not Know Were Missing Body Parts

Apart from the stories of triumph and subjugation, imperialism and individualism, and the evolution of human societies and the changing standard of living, history is all about risk, danger, and adventure. Nothing has ever really changed without those standout historical moments of derring-do, of conquests, wars, battles, explorations, and grand voyages into uncharted territory. Those who found the wherewithal to make history were often rewarded by becoming the legends of history, iconic characters who also happen to be real-life figures who accomplished or committed near-unbelievable feats. And yet, a great many historical stalwarts didn't complete their missions unscathed.

Due to causes like war, wilderness, and communicable disease, some impactful people also lost body parts while they did what they did, be it an arm, leg, eye, hand, or something else. Throughout history, amputation has been a brutal thing, and these people endured their profound injuries before modern medicine. Therefore, it's all the more surprising that they carried on with their lives, as if it was no big deal to get a limb knocked off by an enemy's cannon blast, for example. Here are some real-life historical figures — including military leaders, monarchs, explorers, and war heroes — who were missing a body part.

Horatio Nelson

Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson was so highly regarded and valued by the U.K. that he's one of the few people outside of the British royal family to have been given a state funeral. A towering and vital figure in Great Britain's Royal Navy, Nelson's ships and sailors helped build his country's empire as well as defend it in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, delivering victories in the Napoleonic and French Revolutionary Wars.

In February 1797, Nelson received the order to attack and claim the town of Santa Cruz and its ports in Tenerife, an island off the coast of Spain. His superiors had heard a rumor that Spanish galleons full of valuables were lying in wait there, and they wanted those riches. Nelson staged a nighttime attack on the San Cristobal castle, which housed high-ranking Spanish military officers. The landing went awry and the naval crew was easily spotted, resulting in gunfire from the defenders as Nelson was about to set foot on land. A shot from a musket struck the commander in his right arm, near the elbow, instantly destroying both the humerus bone in several places, as well as the adjacent joint. That evening, upon the ship Theseus, Nelson had the whole arm amputated, without the aid of any kind of anesthesia. That subsequently ended the invasion, and the British and Spanish called a truce.

King Philip II

Alexander the Great's father changed the military forever. After ascending to the throne of Macedonia in 359 B.C., Philip II got his troops into shape through standardized and issued weapons, training regimens, and by instituting a professional, full-time army. All those measures helped Philip II to successfully repel the invading forces of Illyria. Philip II also believed himself to be part supernatural, a descendant of both Hercules and Zeus of Greek mythology, but he certainly wasn't immortal.

According to the writings of ancient Greek historians, how Philip came to lose his eye is a subject of debate, although he definitely suffered the medical calamity in 354 B.C. during his army's attack on the Greek city of Methone. Some accounts hold that Philip was inspecting his troops' armaments when he was hit by surprise with enemy fire: A simple arrow fired from a bow sailed squarely into Philip's right eye. Others say that the injury occurred while Philip was crossing the River Sandanus on the way to the siege of Methone. A painful notion in and of itself, he lost vision in the eye, and then it was completely removed in a crude and ancient form of surgery. Nonetheless, Philip II went on to lead Macedonia and its world-conquering military campaigns for another two decades.

Lord Uxbridge

Born into an aristocratic family in England in the late 18th century, Henry William Paget ascended through the country's finest schools, served in Parliament, and by age 25, had amassed a battalion of soldiers to fight in the French Revolutionary Wars. His battle prowess was rewarded with numerous promotions, and by 1808 he'd reached the rank of lieutenant-general. Four years later, he assumed his birthright and became the Earl of Uxbridge, better known as Lord Uxbridge.

The Battle of Waterloo in 1815 was famously the downfall of domination-minded French emperor Napoleon, but it also marked a major moment in the life of Lord Uxbridge. In the waning moments of fighting, one of the final shots fired from a French cannon made contact with the cavalry officer and almost entirely separated the lord from an appendage. He was standing next to the Duke of Wellington at the time, and in the immediate aftermath, he was recorded to have quipped (via the BBC), "By God, sir, I've lost my leg!" Wellington's response: "By God, Sir, so you have!" The cannonball hadn't fully severed the leg, but the damage was such that a clean and full amputation was a necessary solution.

After it was removed, a Waterloo local swiped the leg and buried it in his yard, before turning it into a war memorial. Subsequently, making a pilgrimage to pay respects to Lord Uxbridge's leg became a fashionable thing to do.

Peter Stuyvesant

In 1664, the North American colonial stronghold of New Amsterdam was invaded by the British Navy, and the outmatched and beaten defenders surrendered the entirety of their colony of New Netherland. New Amsterdam would soon be renamed New York, while other parts of the area would become New Jersey and New England. For the 18 years prior to that changing of hands, New Netherland was governed by Peter Stuyvesant, a Dutch administrator acting on behalf of the Dutch West India Company.

Just before he was appointed director-general of New Amsterdam, Stuyvesant held a similar role as director of the ABC Islands: Aruba, Bonaire, and Curacao in the Caribbean. Between the powers of the Netherlands, Portugal, and Spain, there was much heated colonial positioning in the region, and in 1644, Stuyvesant directed an attack on a Spanish fort. During the melee, a Spanish ship fired a cannonball at Stuyvesant's vessel that struck the commander, and with such force that Stuyvesant required immediate surgery to remove his lower right leg. He was then outfitted with a wooden prosthetic, earning Stuyvesant the moniker "Peg-Leg," which is certainly one of history's strangest nicknames.

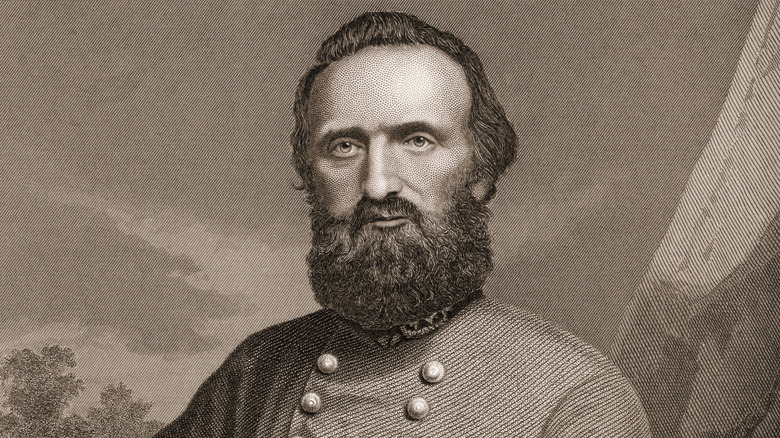

Stonewall Jackson

As an officer trained at West Point Military Academy, Thomas Jackson commanded troops during the Mexican-American War and taught at the Virginia Military Institute. When the Civil War began in 1861, Jackson defected to the Confederacy, and at the Battle of Bull Run, he was so unflappable in the face of Union fire that General Barnard E. Bee compared his fellow general to a stone wall, bestowing upon him his famous nickname. Among the fiercest and most tenacious leaders of the Confederate Army, Jackson notched several wins for the Civil War's losing side, and his military exploits came to an end in 1863. One of the many things that don't make sense about the Civil War was how Stonewall Jackson succumbed to accidental or "friendly fire" at the Battle of Chancellorsville, which was waged in Virginia.

Jackson didn't die on the battlefield, but he was so seriously injured that he had to have his left arm quickly removed by an army doctor. Bound for a mound of other limbs amputated from other fallen troops, chaplain Rev. Tucker Lacy rescued it and had it buried at Ellwood Manor, a nearby cemetery. Eight days later, Jackson died of pneumonia at the nearby Guinea Station, and he was buried at what became the Stonewall Jackson Memorial Cemetery in Lexington, Virginia — apart from his severed arm.

Sarah Bernhardt

Before the arrival of film, the most famous actors were theatrical performers, and one of the best-known of them all was probably French-born Sarah Bernhardt. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, Bernhardt was the toast of Europe for her work at the Odéon and Comédie-Francaise, and won rave reviews for her roles in plays by Voltaire, Shakespeare, and Victor Hugo.

A physically aggressive and very active actor, Bernhardt endured numerous injuries throughout her stage career. In an 1893 production of "La Tosca," she was supposed to fall from a tall castle tower onto a hidden mattress, but the landing spot wasn't properly set up and Bernhardt fell directly onto the stage. Bernhardt didn't slow down her career to recover from any of her injuries, dealing with constant pain as she toured through the great theatres of Europe. She even performed for soldiers on morale-boosting trips to the front lines of World War I, just after she had a leg amputated. The limb, which was seriously injured in the 1893 fall, had become infected with gangrene and needed to be removed. Bernhardt kept up her globe-trotting acting career until 1921, and she died two years later.

Virginia Hall

Following Nazi Germany's invasion of France in 1940, Virginia Hall was forced to leave her job as an ambulance driver with the French military and flee to England. There, she joined the Special Operations Executive, a U.K. espionage agency, which sent her back into France to help set up and support the French Resistance.

Long before the war, Maryland-born Hall had been rejected for U.S. State Department work because of her gender, despite being able to speak multiple languages. Instead, she found jobs in U.S. embassies in Poland and Turkey in the 1930s, and it was on a hunting excursion in the latter country where Hall mistakenly fired a bullet into her own foot. Gangrene set in and spread, and in order to stop the infection from moving into the rest of her body and potentially killing her, Hall had little choice but to have it amputated. She was given a prosthetic leg, which Hall named "Cuthbert."

Hall, the former American diplomat turned Allied spy, was the one operative most feared and hunted by the Nazis. With her name and nationality largely a mystery, the spy walked with the unique gait of someone with an artificial leg: At one point, the Gestapo's entire network of double agents was scouring Western Europe to take her out, seeking to find and identify the individual known primarily as "The Limping Lady." Hall became the only non-military person to be awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for service in World War II.

Douglas Bader

At the age of 20, Douglas Bader had graduated from the Royal Air Force College and was assigned to fly with the No. 23 Squadron. The pilot had an aptitude for tricky aerial maneuvers in his Gloster Gamecock and went on to perform stunts at airshows. In 1931, the No. 23 Squadron replaced its fleet with Bristol Bulldog planes, which Bader was likely less familiar or comfortable with. While performing in an air show at the Woodley Aerodrome outside Reading, Bader lost control of his plane and violently crashed. Among the injuries he sustained was damage to both of his legs so severe that what remained of them were surgically amputated within a few days.

Six months later, Bader had been outfitted with prosthetic legs and had learned to walk without the use of any support. Although he met the physical criteria necessary to fly again, and was intent to do so, the Royal Air Force discharged him. In 1939, with the U.K.'s entry into World War II being a foregone conclusion, Bader was again allowed to re-enter service with the RAF.

Bader flew multiple combat missions and was placed in charge of the No. 242 Squadron. In August 1941, his plane was shot down and hit another plane as it hurtled to the ground. Bader ejected, but in his descent he lost both of his artificial legs, although the right was later found and reinstalled. Bader made multiple escape attempts from Nazi prisons until World War II ended in 1945.

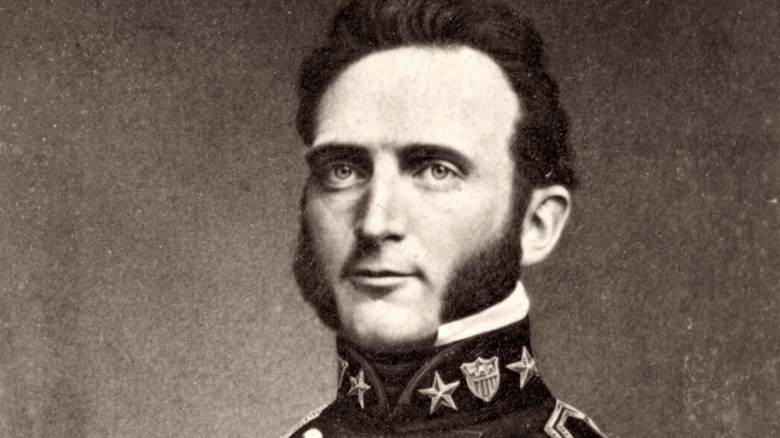

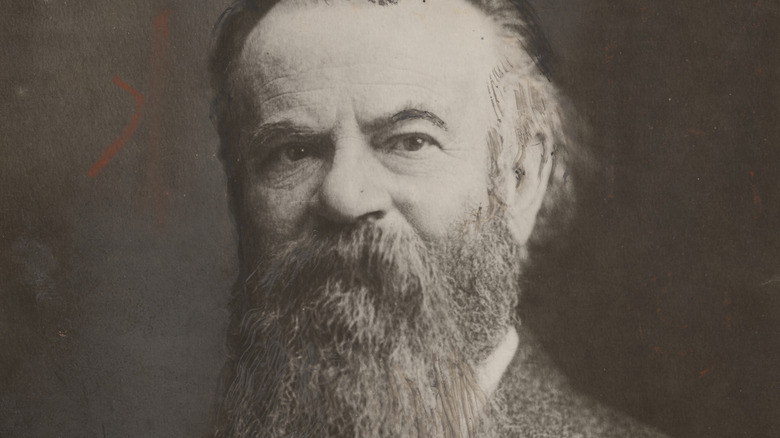

John Wesley Powell

John Wesley Powell was a self-styled explorer from New York who once navigated the entirety of the Mississippi River on his own, but his life's work was interrupted in 1861 when he signed up to fight for the Union Army in the Civil War. He quickly earned a commission as a captain, and participated in the pivotal Battle of Shiloh in April 1862. The Union was victorious, and it was able to make significant movements into Confederate territory.

The Union nevertheless suffered heavy casualties, with 1,754 soldiers killed and 8,408 sustaining injuries, and those were only the confirmed numbers. Among those injured was Captain Powell, who sustained enemy fire so damaging to his arm that, at a makeshift battlefield army hospital, a surgeon had to resort to amputation. Powell's right arm, from just below the elbow down, was summarily removed. After a short period of recovery, the depleted Powell returned to combat duty and earned a promotion to major. In 1869, four years after the end of the Civil War, Powell resumed his exploration missions, heading up a 99-day voyage into the little-explored Colorado River valley and finishing at the Grand Canyon, a feat that led to his position as the director of the U.S. Geological Survey.

Gotz von Berlichingen

In the early 16th century, Bavaria was ruled by constantly feuding barons and dukes. They hired mercenaries to fight their battle, and one of the most sought-after was a knight named Götz von Berlichingen. In 1504, he was conscripted to fight on behalf of Duke Albert IV of Bavaria in an attack on Landshut. Amidst the fighting, a cannonball fired by the defending forces hit von Berlichingen. Some records indicate that the cannonball struck von Berlichingen's sword with such force that it sliced all the way through the warrior's right arm. Others wrote that the cannonball hit the arm and knocked it off. At any rate, von Berlichingen was suddenly left without his hand.

Within a short period of time, von Berlichingen was back on the battlefield with a new hand made of iron. Hinged fingers allowed von Berlichingen to hold a sword, and the knight resumed his career. A few years later, he got a new, better iron appendage. Consisting of a forearm segment as well as a hand, it attached with a strap of leather and featured hinges in all of the places that biological knuckles would be, along with spring-loaded machinery that kept fingers where von Berlichingen wanted them to be. He could reportedly hold a sword or a quill, or use a horse's reins, all with relative ease. That hand is now on display in a museum in Jagsthausen, Germany, hometown of the warrior who was rightfully nicknamed Götz of the Iron Hand.

Christopher Newport

A 24-foot-tall bronze statue of Christopher Newport overlooks an eponymous university in Newport News, Virginia. Unlike the real Newport, and to the chagrin of many American colonial-era historians, it's not an accurate rendition of the man, because it shows Newport as having two biological hands. He was the captain of the Susan Constant, the main ship of the first voyage of English settlers that would establish the Jamestown Colony in 1606, and would go on to make multiple supply-run return trips. However, Newport became a seasoned seafarer in his early years as a privateer, and thanks to the harsh reality of life as a pirate, he left that career missing a limb.

In the late 16th century, British merchants had hired Newport to troll the West Indies to loot and pillage passing Portuguese and Spanish trading vessels. It was during one of those raids in 1590, of two loaded Spanish ships, that Newport got into a fight and lost most of his right arm. For the remainder of his piracy and subsequent legitimate sailing careers, and indeed his lifetime, Newport wore a hook in the place of his violently amputated hand.