The Incredible Escape And Recapture Of El Chapo

The name Joaquin Archivaldo Guzman Loera probably doesn't ring a bell, but his nickname, "El Chapo," almost certainly does. It means "short," and it's a common, playful label for men of short stature in Mexico. This is where El Chapo operated for two long stretches, separated by a prison term, as one of the most notorious, dangerous, and, to be frank, successful criminals in recorded history. As the head of the Sinaloa Cartel, he became an almost mythical figure for the way he somehow tracked tons of illicit and illegal drugs into the U.S. For his second act, El Chapo raised the stakes: He escaped from one of Mexico's most highly secure prisons in 2015 in a manner both baffling and frightening.

A decade on, and El Chapo remains locked up, serving out a life sentence in a prison that's been able to keep him behind bars. Here then is how he got to that point. From his rise through a cutthroat and criminal underworld to his status as a prisoner who's escaped jail a surprising amount of times, the reestablishment of his empire, and the story of how he somehow survived one of the most famous manhunts in American history.

How Joaquin Guzman Loera became El Chapo

There's some discrepancy on dates, but it's known that Joaquin Archivaldo Guzman Loera was born in the 1950s in the northwestern Mexican state of Sinaloa. In the 1970s, he made the first steps in his crime career by doing work for one of the state's drug traffickers from the Guadalajara Cartel, Hector "El Guero" Palma. Specifically, Guzman helped oversee efforts to move large amounts of cocaine and marijuana into the U.S. from the Sierra Madre mountains. He earned a reputation as a tough and merciless boss, not hesitating to kill his own runners if they displeased him. In fact, he was so effective that he was introduced to one of the cartel's founders, Miguel Angel Felix Gallardo. Working first as a chauffeur, Guzman was promoted to the high-position head of logistics, responsible for mapping out drug shipments from suppliers in Colombia, using planes, boats, and land vehicles.

In 1989, Gallardo was arrested and sent to prison for the murder of a U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency operative. At that point, the Guadalajara Cartel was splintering. Guzman wound up in charge of one branch, which became known as the Sinaloa Cartel. One of the most lucrative and powerful of all drug trafficking organizations, under Guzman's leadership, it transported tens of billions of dollars worth of cocaine, heroin, and marijuana into the U.S. in the early 1990s. And that's when Guzman, by now known as "El Chapo," started showing up on the radar of U.S. law enforcement agencies.

He spent nearly a decade in prison

American authorities cut off drug import channels at entry ports in the 1990s, making Mexico the only way to smuggle in contraband — which made El Chapo even more powerful. He and the rest of the Sinaloa Cartel were made to defend their empire against other criminal enterprises, first and foremost the Tijuana Cartel. Tensions bubbled over into a shootout at Guadalajara International Airport in May 1993, with the Tijuana contingent riddling a car with bullets. The group thought that El Chapo was inside the vehicle, but he wasn't — Juan Jesus Posadas Ocampo, Archbishop of Guadalajara, was, and he died in the violence.

Because Guzman was linked to the crime, he was named a most wanted fugitive by Mexican authorities, who plastered his face and information across Latin American media. Weeks later, he was caught in Guatemala and extradited to Mexico to face trial for his crimes. Convicted, he was sentenced to 20 years in prison for conspiracy, drug trafficking, and bribery — the latter charge coming from a $1.2-million protection payment offered to the Guatemalan military. His first eight years in prison at the Federal Social Readaptation Center No. 1 in Juarez were relatively pleasant. El Chapo could bribe guards and do whatever he wanted, which was to bring in women and erectile dysfunction pills.

He broke out of prison for the first time in 2001

Almost halfway through a sentence that proved to be less than severe because he had the ways and means to make life in prison very comfortable for himself, El Chapo decided it was time to leave Mexico's Federal Social Readaptation Center No. 1, also known as El Altiplano or Puente Grande. The main reason, or why he needed to leave at that exact point in time: He believed he was about to be extradited to the U.S. to face another trial for his substantial crimes. If convicted, he'd probably be sentenced to live out many more years in a much more punishing facility, one staffed by guards he wouldn't be so easily able to manipulate or pay off.

In January 2001, El Chapo mounted his escape. It wasn't a sophisticated plan — he didn't utilize substantial manpower or the network of tunnels he'd had built to move his cartel's drugs into the United States. No, his grand exit was fairly straightforward and out in the open. According to some reports, El Chapo hid inside of a laundry cart, which, when taken off site for processing, gave him the escape route he needed. Other accounts point to the more likely scenario of El Chapo merely walking out the prison's gates when he was ready to leave — he'd bribed the guards enough money to let him leave in that nonchalant manner.

He went back to work

While El Chapo was incarcerated for most of the 1990s, he left control of the Sinaloa Cartel to Ismael "El Mayo" Zambada. When he broke out of prison in 2001, he reclaimed his authority. Over the next 13 years, while the most hotly pursued fugitive in North America, El Chapo built the Sinaloa Cartel into a massive, sophisticated illegal drug operation. It was complete with logistics and product distribution operations previously only achieved by legitimate global retail companies.

Throughout the early 2000s, El Chapo's company utilized land, water, and sky routes — along with a system of warehouses situated in multiple major U.S. cities — to keep much of the Western world supplied with cocaine, heroin, marijuana, and methamphetamine. The Sinaloa Cartel grew to be one of the most cash-laden on earth, generating billions that afforded El Chapo the opportunity to influence Mexican politicians to let him be. Over a 13-year period, El Chapo was rarely seen, occasionally popping up at Mexican resorts, in small towns in Central America, and throughout South America.

By the time authorities came to investigate, he'd be long gone. At one point, the Mexican federal government ran three paramilitary units with the sole purpose of capturing and/or killing El Chapo. But he was quiet and careful, using bribes and violence and employing a large array of killers whose death toll was in the thousands. The most gruesome incident happened when his cartel took over Ciudad Juarez, a border town and critical junction for drug trafficking.

El Chapo got caught in 2014

After more than a dozen years on the lam, but rarely venturing outside of his home region and his cartel's base of operations in western Mexico, El Chapo's era as a federal fugitive and prison escapee— and extraordinarily successful drug trafficker — began to wind down in December 2013. From 2001 on, agents from various Mexican and American law enforcement agencies struggled to find El Chapo. He was almost certainly somewhere in the Sierra Madre Mountains during that time, flitting between a series of farms and houses situated in very remote areas. Local farmers were loath to assist authorities, refusing to provide any specific information on the whereabouts of who they knew was El Chapo but had started calling "El Senor," a new nickname that meant the same thing as "The Boss."

But then, a team of Mexican and American agents pinpointed El Chapo's location: He was hiding out in a nondescript condo near the beach in Mazatlan. They were able to arrest El Senor when after apprehending several cartel lieutenants in the area, they discovered that a network of safe houses were connected via underground tunnels carved out of the municipal sewer system. In January 2014, El Chapo was arrested, a moment celebrated on Mexican TV on a naval base with the president in attendance. He was swiftly sent back to his old prison.

He broke out of prison the second time in 2015

On Saturday, July 11, 2015, cameras trained on El Chapo's cell at the Federal Social Readaptation Center in Juarez gathered footage of the inmate heading into the room's connected shower. Nobody saw him after that. About 17 months after he'd been recaptured after escaping the same facility in 2001, El Chapo had once again managed to break out of prison.

A massive search effort ensued. All flights out of the local Toluca airport were grounded, with authorities thinking that El Chapo could make his way out of the country that way. Meanwhile, back at the prison, officials looked around the cell and found the method by which it was very likely the drug lord made his low-key escape. For decades, El Chapo had made use of subterranean tunnels to move product from Mexico to the United States, unbothered by attention from law enforcement. He's used a similar method to leave prison. There'd been a trapdoor of sorts installed in the shower in El Chapo's cell, and he climbed through it to reach an underground tunnel that stretched from a warehouse to an abandoned building in a town about a mile away from the prison. Proper lighting and ventilation machinery had been built into the tunnel, which was lined with track and outfitted with a motorcycle-like vehicle probably used to move dirt. Once the tunnel — an inch taller than El Chapo himself — the inmate escorted himself to freedom.

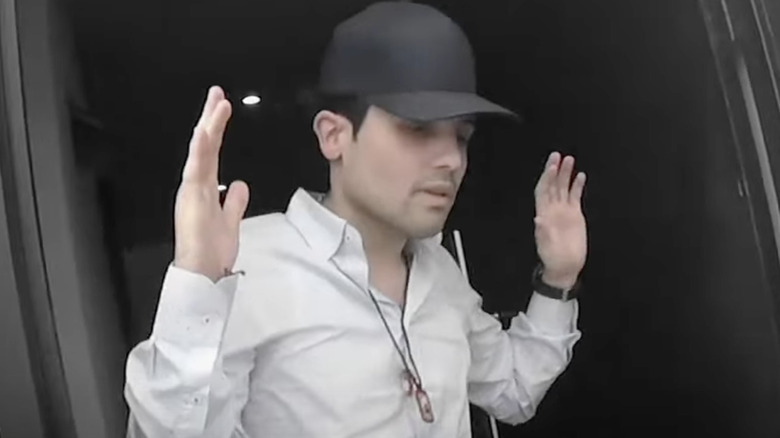

Fugitive El Chapo did a high profile interview

Already a celebrity with a connection to an infamous criminal, actor Sean Penn spent time in jail himself, and that's something he had in common with El Chapo. Three months after his second prison escape, while he was a fugitive from justice, El Chapo summoned Penn for a meeting. Penn agreed, but not after first pitching his meet-up with the world's most wanted drug lord to Rolling Stone as an exclusive interview with El Chapo. Two flights and a seven-hour SUV ride delivered Penn to a hard-to-reach spot outside Cosalá in El Chapo's home state of Sinaloa.

The main order of business: El Chapo wanted his life story to be turned into a major film, and he wanted Penn, an actor and director with Hollywood clout, to make it happen. This plan was instigated by another actor, Kate del Castillo, who was a friend of El Chapo's going back to when she wrote a tweet in support of the criminal in 2012. She was at the meeting too, and in 2014, his lawyers gave her a phone to text El Chapo in prison details of her plan to make his biopic. Penn wasn't sure if he wanted to make the movie or not, and he respectfully put off El Chapo before he returned to the United States. None of the parties involved knew that they were under surveillance by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency and National Security Agency.

How authorities tracked him down

Immediately after the Mexican government figured out the specific area where El Chapo was laying low, thanks to an assist from the kingpin's Sean Penn movie pitch meeting, the raid was on. They set upon El Chapo's 18 known homes throughout the states of Durango and Sinaloa, but the wanted criminal escaped. Then, the multi-agency operation got the tips it needed in January 2016. In the beachside city of Los Mochis, Sinaloa, construction workers started showing up at a property linked to El Chapo, and phone taps picked up on conversations about an important and impending arrival. In the early morning hours of January 8, surveillance noticed a white van, matching those favored by El Chapo's cartel personnel, delivered a large order of tacos to another home in the vicinity.

A unit of Mexican Marines jumped upon the latter property, enduring heavy gunfire from the cartel members inside, and they noticed numerous subterranean escape hatches. It was through one of those — hidden behind a mirror in a closet — that El Chapo and a close associate had escaped. After making their way into a populated retail area, El Chapo and his employee stole a car, abandoned it when it broke down, commandeered another one from a woman and her two children, and sped off. The Marines gave chase, and a few hours later, they cornered El Chapo and took him into custody.

He probably won't escape again

Following the apprehension of El Chapo in January 2016, the Mexican government figured the cartel leader would return to a prison in his home country. Then, fearing another El Chapo escape and the humiliation that would bring, Mexico allowed for the transfer to happen. El Chapo arrived in the U.S. in January 2017, after a nearly year-long process of appeals was ultimately ended by a Mexican federal court. The extradition was legitimate because El Chapo's crimes included trafficking drugs into the U.S., and also, if he were found guilty, he would be potentially sentenced to a prison term in a very secure American prison.

In February 2019, following a three-month courtroom trial, a federal jury found El Chapo guilty on a 10-count indictment and for leading a continuing criminal enterprise, which involved 26 drug charges and a count of murder conspiracy. All told, El Chapo was found guilty on charges involving drug trafficking, gun, money laundering, and being responsible for a death. Five months later, U.S. District Judge Brian M. Cogan decided on El Chapo's punishment: Life in prison, plus an additional 30 years. He was also directed to pay out more than $12.6 billion in forfeiture. El Chapo will likely spend the rest of his life in an extra secure "Supermax" facility in Colorado, ADX Florence. The prison is purportedly impenetrable and escape-proof, a fitting and ironic home for an inmate who has left prison of his own volition twice.

He's made some friends in prison

Life in a federal supermax prison is categorically and by design unpleasant for anyone, particularly El Chapo. He's housed at Colorado's ADX Florence, one of the most secure prisons in the U.S., with exactly zero prisoner escapes. El Chapo resides in a single-occupancy soundproof cell that measures 84 square feet, and is equipped with little more than a simple bed, desk, stool, concrete shelf, sink, toilet, and four-inch window at waist level. He's in there for 23 hours out of every day, the prison remains on lockdown all the time, and solitary confinement is essentially standard operating procedure.

Despite all the limitations in place, El Chapo has managed to get friendly with the resident in the cell directly next to his: Convicted Mafia affiliated con artist and jewel thief James Sabatino. By 2025, they had been neighbors turned friends for five years by 2025, when they filed a joint petition with the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Florida (El Chapo and Sabatino share a Miami-based lawyer) asking if they can spend their one-hour daily allotment of non-cell time together. El Chapo soon withdrew the petition, but he's also asked on multiple occasions if he could have increased phone call and visitation privileges. As there's evidence that El Chapo conducted cartel business via secret phones during a previous prison stint, that request was denied.

There's another generation of El Chapo

When someone is sentenced to life in prison, it really does mean that, barring a successful appeal or exoneration, they're likely to wile away the rest of their days behind bars. With international kingpin and multiple prison escapee El Chapo firmly locked up in a Colorado supermax prison, leadership of his far-reaching trafficking and cartel organization fell to someone else. Following the 2016 arrest and extradition of El Chapo, the Sinaloa Cartel's line of succession landed on the indisposed criminal's four sons, who called themselves Los Chapitos.

One of those men, Ovidio Guzman Lopez, took a particularly assertive role in the organization, arranging and maintaining the sophisticated network that brought cocaine, heroin, fentanyl, and chemicals used to manufacture other illegal substances from Mexico into the U.S. Like father, like son: Guzman Lopez avoided border checkpoints by utilizing hidden tunnels, as well as railroad cars and air transport. In 2025, two years after he was arrested and extradited to the U.S., Guzman Lopez delivered a guilty plea to two charges of knowingly engaging in an ongoing criminal enterprise and two charges of drug conspiracy. As for the other Chapitos, as of October 2025, Joaquin Guzman Lopez is awaiting a trial in Illinois on drug trafficking charges, while Ivan Guzman Salazar and Jesus Guzman Salazar have been charged and remain at large.