The Bizarre Life Of The Man Who Killed Spartacus

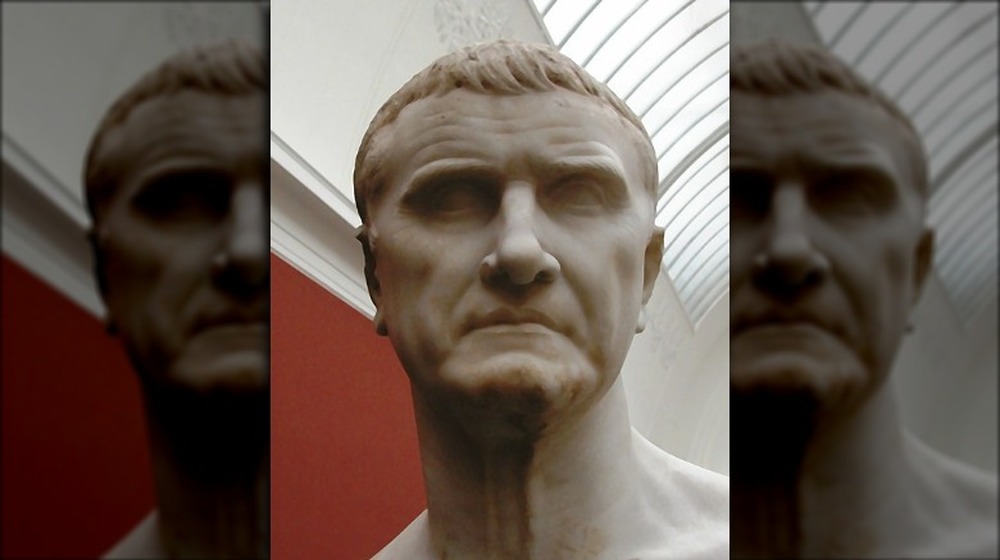

Marcus Licinius Crassus was a Roman politician and general who was also probably the richest man Rome had ever seen. His insatiable hunger for wealth led him to acquire most of the property in Rome and gain great political power by keeping much of the Roman Senate in his pocket. He gained fame for both putting down the slave rebellion led by the gladiator Spartacus and as a member of the powerful First Triumvirate, but despite his successes and great wealth, he was always jealous of the military accomplishments of his rivals Caesar and Pompey. In the end, his life serves as an object lesson that past-their-prime billionaires who made their fortunes off crooked real estate deals probably shouldn't invade Iran.

If you only know Marcus Crassus as an antagonist from the life of Spartacus or as Julius Caesar's less famous friend, there's much to learn about him and the odd and crooked ways he made and kept his money, as well as his almost comically tragic end. Here are some of the strangest details in the bizarre life of the richest man in Rome, the man who killed Spartacus.

Marcus Crassus succeeded despite his horrible name

The way the Roman naming system worked in the late Republic meant that male citizens typically had three names. The first name was a personal name, largely meant to distinguish you from your brothers. The second was the name of your larger clan, while the third name indicated which branch of that clan you were from. So Marcus Licinius Crassus was from the Crassus branch of the Licinian clan. Many of these third names originated as nicknames, often based around a notable physical trait. Crassus, in this case, means "fat," "stupid," or "gross," the source of our English word "crass." That doesn't mean that Marcus Crassus himself was fat and gross, however, just that one of his ancestors was.

One branch of Crassus' family got a nicer nicknamed tacked on. They were known as the Crassi Divites or the "rich Crassuses." Despite his renown for his great wealth, however, Marcus Crassus wasn't actually part of this branch, and his much-lauded riches were acquired, not inherited. And here's one last name fact. According to the famed Roman orator Cicero (whose own name seems to indicate he had an ancestor with a chickpea-shaped wart), Marcus Crassus' grandfather — also named Marcus Licinius Crassus — was given the Greek nickname "Agelastus" ("the unlaughing") because he only smiled once in his whole life. What was the thing he grinned and laughed at? Apparently, a donkey eating thistles. Maybe you had to be there.

Crassus hid in the world's fanciest cave to keep from being murdered

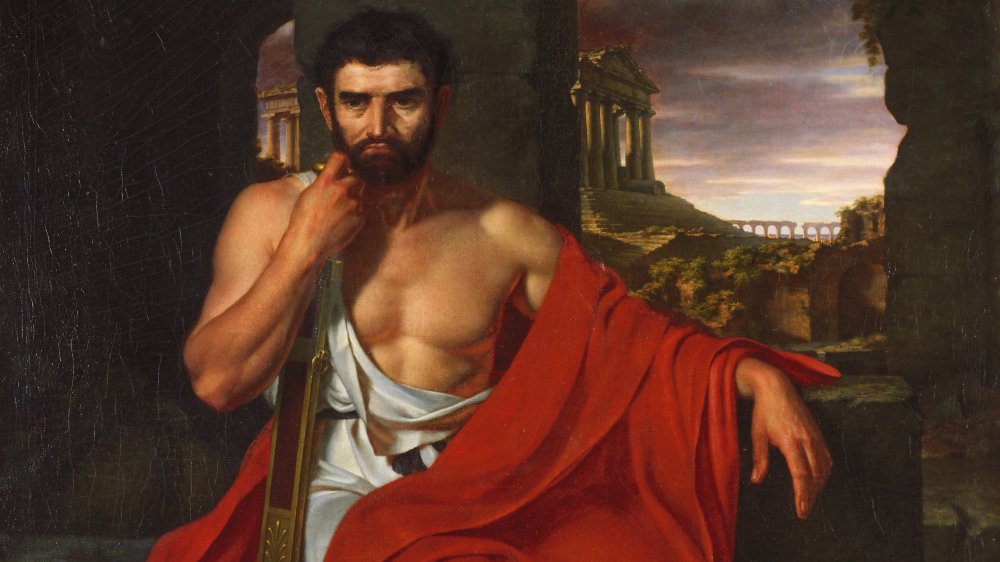

There's not enough space here to explain the entirety of late Republican Rome, but suffice it to say that the first century BCE was full of civil wars between various strong men competing for control. One of the most notable of these conflicts was between the aristocratic general Sulla and the populist general Gaius Marius (Julius Caesar's uncle, pictured above). According to the historian Plutarch, the patrician Crassus family had supported Sulla in his march on Rome in 88 BCE, and so the whole family found themselves at the receiving end of death warrants when Marius and his allies held power. Notably, Crassus' father and brother died at the hands of Marius' allies

Not wanting to wind up murdered himself, the young Marcus Crassus fled to Spain, where he lived in a cave for eight months. But being a fancy lad, he lived in possibly the most luxurious cave of all time. Plutarch describes it as being by the sea, enormous in size, and full of light and fresh water. Plus, Crassus took three friends and ten servants with him. A slave belonging to the man who owned the land the cave was on brought fancy meals to Crassus every day, and two female slaves tended to, you know, his other needs.

The man who killed Spartacus made his fortune flipping houses

After Gaius Marius and his main ally Cinna had died, Crassus came out of his cave and recruited 2,500 men from his father's clients in the area, eventually joining forces with Sulla (gaining a "position of special honor") and helping him fight Sulla's second civil war. As Plutarch explains, it was through his close relationship with Sulla that Crassus began accumulating his vast wealth. While some of Crassus' riches came from silver mines, selling slaves, and money-lending, much of his holdings came through house-flipping shadier than anything you'll ever see on HGTV.

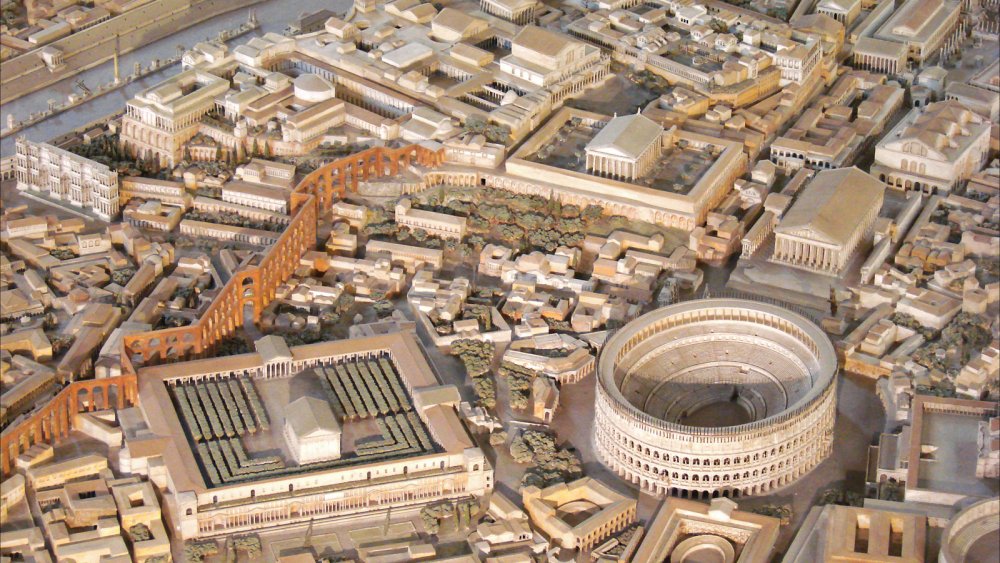

Following his victory, Sulla put many supporters of Gaius Marius to death, after which he seized their property as "spoils of war" and auctioned it all off at rock-bottom prices. The person who most benefited from this was Crassus, who snatched all of this bloodstained real estate up. Crassus was also renowned for his horde of well-educated slaves, among whom he made sure to include architects and builders who could restore his newly acquired properties to lead to a large return on his investment. By these shady means, Crassus came to own most of the buildings in Rome, and he accumulated a wealth of 7,100 talents. According to Business Insider, historians say that could be anywhere from $200 million to $20 billion. So yeah, a lot. To be fair, though, he had begun with 300 talents, which isn't exactly starting from nothing.

Crassus had his own private army

If there was one thing Marcus Crassus loved, it was money, and he had a great facility in getting it. But if there was one thing that he wanted but couldn't get, it was military glory. Marcus' father, Publius, had served as commander in the Roman province of Iberia from 97 to 93 BCE, and during that time, he'd won a military victory there over the Lusitani tribe, earning himself the honor of a triumph, which was basically an enormous, ornate parade in celebration of a victorious commander. Since Publius had gotten one, Marcus wanted one, too.

To that end, Marcus Crassus assembled his own private army, over which he placed himself as general. In fact, Plutarch reports that Crassus was known to say that no man could count himself rich until he could afford his own army. Crassus' forces were made up of thousands of men, who were almost certainly slaves, and even included a sailing fleet. Even with the goal of winning honor for himself, though, Crassus couldn't keep his infamous money lust at bay. With his assembled forces, he would travel from city to city and extort money from them in order to fund his military campaigns. Plutarch says Crassus was even accused of straight-up sacking a city, but he himself denied this charge. (In case you were wondering, no, Crassus never got his triumph, much to his chagrin.)

He invented fire departments ... but for extortion

Of all the innovations you might expect to have arisen from a money-hungry real estate mogul and wannabe war hero, the noble and selfless sacrifices of firefighters might not be one of them. And yet, by most accounts, the first ever urban fire department was developed by Marcus Licinius Crassus. By now you might be wondering, "What's the angle?" And you're right to do so. As Plutarch explains, Crassus' private fire brigade was as much a money-making scheme as anything else he put effort into.

Roman buildings were densely populated and very close together, and so the risk of fire was always extremely high. Whenever such a building caught fire, Crassus would arrive with his slave fire brigade, but they would do nothing to put out the fire. The firefighters would stand by while Crassus negotiated the purchase of both the burning building and any adjoining buildings at criminally low prices from grieving and terrified property owners. If the owner agreed to Crassus' price, his men would put out the fire and then — since they were, of course, builders and architects — rebuild the properties nicer than before so that Crassus could lease them back to their original owners at inflated prices. If there was no sale, Crassus would let the building burn. It was for this reason — plus gathering up the property of Sulla's executed enemies — that Crassus was said to have made his fortune from "fire and war."

He worked his whole life with a man he despised

During his early days serving under Sulla, Marcus Crassus first met and worked together with another promising young man named Gnaeus Pompeius (pictured above), known to modern audiences as Pompey the Great and known to his adversaries as "the teenage butcher." As the Encyclopedia Britannica explains, despite Crassus' special position of honor among Sulla's allies, the aristocratic dictator showed even more respect toward Pompey, and thus a lifelong rivalry was born. As much as Crassus might've desired a triumph to equal his father, it was seeing his contemporary Pompey rack them up that spurred on his zeal for military glory even more.

The two generals were basically the textbook definition of frenemies. They clearly loathed each other, but for political expediency, they worked together as allies for almost their entire lives. Twice, the two of them served together as consuls (basically co-presidents), but the first time, Crassus had to humble himself and ask Pompey to endorse his candidacy, which he did because he wanted Crassus indebted to him. Once in office, the two argued about everything and basically achieved nothing. The Ancient Encyclopedia recounts a legendary moment of pettiness between them. According to the story, when Pompey received a triumph that Crassus felt he deserved, Crassus brought attention back to himself by bankrolling enormous parties. And when he overheard someone refer to Pompey by his honorific nickname, "the Great," Crassus burst out laughing and said, "Why, how big is he?"

Crassus' greed saved him from a sex scandal

As the Ancient Encyclopedia points out, Marcus Crassus had no shortage of virtues. Despite his Scrooge McDuck-like wealth, he wasn't a miser. He was known to be extremely generous to his friends, and a large part of his political popularity can be attributed to his willingness to spend lavishly on public festivals and entertainments. He was well-versed in philosophy, and his skills as an orator were so strong that even the legendary rhetorician Cicero was hesitant to ever argue with him in a legal setting. But despite his many strengths, his one vice — greed — was so powerful that it was said to have outweighed all the good. In fact, in one notorious case, he was able to use his greed as a defense against an accusation of another crime.

According to Ancient Origins, Crassus was once brought to trial on charges of getting too intimate with a Vestal Virgin, one of the priestesses of the goddess Vesta who were supposed to remain, well, you know. If found guilty, Crassus would've been executed, with his wealth and reputation lost. However, Crassus explained they weren't hooking up. Instead, his explanation was that, the priestess — his cousin, Licinia — owned a suburban villa that he'd been trying to convince her to sell him at a low price. Ultimately, the judge agreed that Crassus was more likely to be greedy than lustful, and so both Crassus and Licinia were spared execution. Even after this, Crassus hounded Licinia until she sold him the villa.

Crassus killed Spartacus but lost the credit

If you get most of your ancient history knowledge from premium cable shows, there's a chance you know Marcus Crassus best as the guy who killed Spartacus. And considering his successful quelling of the slave rebellion led by that famous gladiator was the closest he ever got to the military triumph he so desperately desired, he might be happy about that. As the Ancient Encyclopedia explains, the slave army led by Spartacus was made up of as many as 120,000 men who were laying waste to southern Italy and had already defeated two Roman armies when Crassus was sent to put the rebellion down. His first attempt was unsuccessful due to a lieutenant disobeying Crassus' orders. In response, Crassus reinstituted the ancient punishment of decimation, where one-tenth of that lieutenant's unit was randomly chosen to be executed in front of the entire army.

Once Crassus had killed a bunch of his own men as a, uh, morale booster, the eight legions under his command successfully brought down Spartacus' army and lined the Appian Way, arguably the most important road in Rome, with 6,000 crucified slaves. (However, Spartacus himself wasn't there. Despite what the Stanley Kubrick movie shows, he likely died in battle). Despite Crassus' success, it was his rival Pompey, who — having caught some of the escaped slave forces on his way back from Spain — got all the credit and the formal triumph for Crassus' victory.

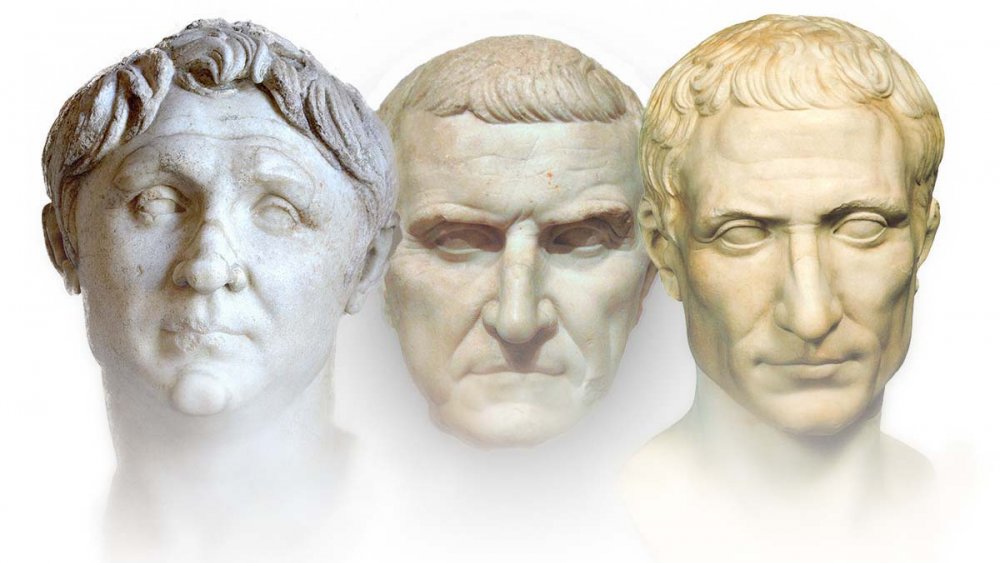

Crassus was the First Triumvirate's 'other guy'

Remember that episode of Seinfeld where Elaine goes to see one of the Three Tenors but can't remember his name? You know, not Pavarotti or Domingo but the other guy? Well, Crassus was the other guy from one of the most famous and powerful gangs of three in history, that uneasy alliance of powerful rivals known as the First Triumvirate. As the Ancient Encyclopedia explains, the three men of the triumvirate — Julius Caesar, Pompey the Great, and Marcus Crassus — put aside their personal animosity to try to bring political order to the chaos of the late Roman Republic (although if you've read Shakespeare's Julius Caesar, you might know that this plan, uh, doesn't work out).

By 62 BCE, Crassus had become something of a patron of the younger Caesar, whose considerable political debts Crassus paid off. And the young Caesar, still before his campaign in Gaul that would lead to him being basically Rome's main dude, knew that pooling Crassus' wealth, Pompey's military might, and his own political ambition would allow them to accomplish great things. He managed to reconcile Pompey and Crassus and sealed his alliance with Pompey by giving him his daughter Julia in marriage. After the death of Crassus, however, the alliance crumbled and ended with Pompey's head in a box and Caesar as the last man standing (for a while).

A man cursed Crassus to stop him from an ill-planned invasion

How did Marcus Crassus die? He led a campaign that was considered so reckless, stupid, and greedy that after his death, he became known as "the Fool of Carrhae." He died a failure, leading also to the death of his son and most of his army, as well as to the collapse of the First Triumvirate and ruining any hope of a diplomatic relationship between Rome and Parthia. While it's true that hindsight and history have made a convenient scapegoat of Crassus, it's hard to argue that he wasn't acting on greed and jealousy of his more successful allies, Caesar and Pompey.

But let's back up. According to ThoughtCo., by 53 BCE, Crassus had accumulated even greater wealth as the governor of Syria, and he thought to expand that wealth (and maybe gain a little military triumph) by invading Parthia, an empire that covered much of the Mideast, including Iran and parts of Turkey. The Roman Senate strongly urged against the 60-year-old Crassus, who hadn't fought a battle in 20 years, leading an expedition against a mighty empire he knew nothing about. Roman officials tried to show how bad of an idea this was by having public fortune-tellings reveal bad omens. They even tried unsuccessfully to arrest him. One official even performed a ritual curse on Crassus at the city gates. It didn't stop him, but the curse might've worked.

He couldn't wrap his head around horses

As ThoughtCo. points out, Crassus made a number of poor choices in his Parthian expedition. First, Crassus turned down an offer of nearly 40,000 troops from the king of Armenia if he would lead his invasion force through Armenia, a safer route. Instead, Crassus crossed the Euphrates and took the much more dangerous overland route that was suggested to him by a treacherous Arab chief. His main problem, however, was that Crassus assumed his enemies would use the same kind of infantry tactics that the Romans themselves used and that they had encountered with other people of the region. This was not at all the case.

Ultimately, the numerically superior Romans weren't ready for the Parthians' patented horse-and-arrow technology. Crassus urged his men to maintain battle formation until the Parthians ran out of ammunition, a thing which didn't happen, as they had camels loaded up with arrows and waiting for them. The Parthians would ride close, rain arrows down on the Romans, fall back, get more arrows, and attack again. They were also known for their ability to ride backwards and shoot behind them. Crassus' men threatened mutiny unless Crassus parleyed with the Parthians. Crassus, mourning his son who'd died in battle, reluctantly agreed, but when the Romans suspected a trap, a scuffle broke out that left Crassus and his men dead at Carrhae.

The man who killed Spartacus finally got his triumph ... in the most tragic way possible

While no one really knows what happened to Marcus Crassus following his death, Roman sources reported all sorts of rumors and legends as to the postmortem adventures of Rome's richest man. As ThoughtCo. reports, one story that the Romans clearly shamelessly ripped off from Game of Thrones claims that the Parthians poured molten gold into Crassus' mouth as a symbol of his thirst for wealth. Some say that his body was dumped unceremoniously among the corpses of less famous people, left unburied to be eaten by animals and birds. Somewhat stranger, however, is the story from Plutarch that the Parthian general sent Crassus' head to the king of Parthia as a wedding gift for the king's son. At the wedding, Crassus' head was placed on a stick and used as a prop for a performance of Euripides' play The Bacchae, which, to be fair, is a play that ends with a dude's head on a stick.

Plutarch also records one final indignity for Marcus Crassus. The Parthians took a different Roman prisoner who bore some resemblance to Crassus and dressed him in women's clothing, after which they mockingly addressed him as "Crassus" and "imperator" (commander), leading him in a farcical procession of camels dragging severed Roman heads that they mockingly called a triumph. After his whole life of trying to get one so bad, this was probably not the triumph Crassus had been hoping for.