The Brutality Of 19th-Century Prisons

Prior to the American Revolutionary War, which ran from 1775 to 1783, the United States criminal justice system was less about punishment and reform and more about embarrassment. It was reportedly common for non-capital offenders to be branded, whipped, mutilated, or subjected to public humiliation. The English criminal code formed the basis for this pre-1800s justice system that was found in many regions of the United States at the time. Yet historians say that compared to how things were in England, criminals in America were more likely to be forgiven — especially for less severe crimes — and rarely put to death.

Moreover, while the concept of imprisonment (or placing into captivity people who were undesirable in society, for various reasons) has been theorized to be as old as cannibalism, it's difficult to paint an accurate picture of how the prison system developed in America before 1775. What's known is that prior to the reformation of the country's prison system, the majority of jails across the country weren't built to be permanent confinement rooms. Rather, accused persons and criminals awaiting trial were held there as authorities decided on their fitting punishment.

A major shift took place during the earlier half of the 19th century. Two similar but competing approaches to incarceration, originating from prisons in two different states, began to shape how America enacted justice upon those it deemed to be criminals. This evolution came with its own problems, all of which contributed to making 19th-century American imprisonment a brutal, hellish experience.

The Pennsylvania System (aka the Separate System)

When Pennsylvania's Eastern State Penitentiary first opened its gates in 1829, the United States got a taste of what would be called the "Separate System." The penitentiary model was inspired by ideas from the Quaker movement revolving around using confinement instead of capital punishment to punish and reform criminals. (Read about the history of the world's first penitentiary.)

Under the Separate System, prisoners lived, worked, ate, and exercised alone in individual cells with attached yards. They weren't even allowed to walk around said yards simultaneously or talk unless explicitly told to do so. The inmates were also under heavy surveillance and followed strict protocols. Work (e.g., simple crafts) was conducted inside the cell, and religious or moral instruction was delivered individually by chaplains or authorized visitors.

While the system was designed to produce penitence through solitude rather than through congregate labor, it became infamous for prolonged isolation's effects on health. We now know that continuous solitary confinement can cause mental breakdowns, hallucinations, and other harms. Furthermore, prisoners were masked or hooded during movements, preventing recognition and enforcing non-communication. The penitentiary's architectural features also minimized sound and sight.

It was perhaps Charles Dickens who best summed it up: As reported by The New Yorker, after visiting a Pennsylvania prison in 1842, he called solitary confinement "immeasurably worse than any torture of the body." Initially popular in many jurisdictions in the United States, adoption of the Separate System waned by 1833, with only three states (Maryland, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania) continuing to adhere to the system.

The Auburn System (aka the Congregate System)

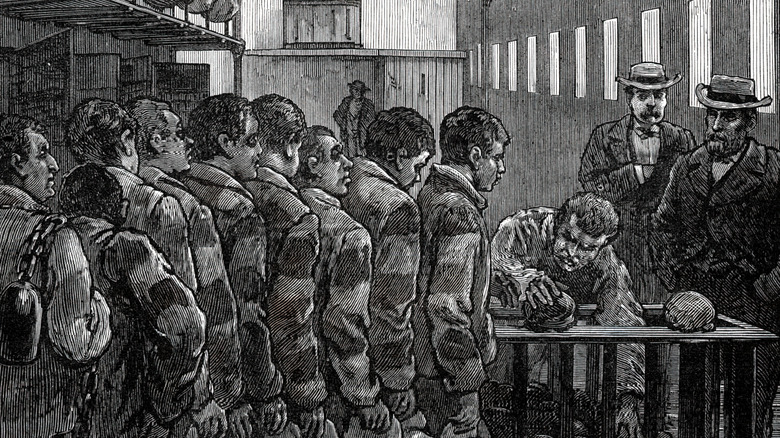

If you're familiar with the story of the world's first person executed by electric chair, then the name "Auburn Prison" may ring a bell. The facility was opened in 1816 after New York had authorized the construction of a second state prison after the first one, Newgate, was deemed inadequate. Auburn's defining rules were solitary confinement at night and strictly noiseless, regimented group labor by day in a factory-like environment. Per JSTOR, early use of extended solitary confinement at Auburn before 1821 reportedly produced what the New York governor called extremely "dire" results, after which administrators shifted to the congregate-by-day format.

By 1823, the Auburn System (aka the Congregate System) had emerged in New York. These features were publicized and copied, making Auburn a model for other U.S. prisons (e.g., Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Vermont, and Washington, D.C.) during the early half of the 19th century. In contrast to the Solitary System's adherence to non-violence, under the Congregate System, violations were punished in pursuit of what was called "redemptive suffering." There were lashings with the multi-headed cat-o'-nine-tails whip and, later on, "cold head-baths" for naked prisoners in what was essentially a torture chair.

The regime also imposed lockstep marching and tightly controlled movement. Inmates wore striped uniforms, and those who spoke or broke formation could be beaten into submission. Additionally, administrators were able to exploit the prisoners through silent labor, generating income that allowed the rapidly overcrowded facility to become self-sustaining. Ultimately, the Auburn System created conditions widely and fiercely criticized in reform debates for their harshness, despite its reputation for order and efficiency.

The infamous Virginia State Penitentiary

Inspired by the core ideas that fueled the Separate System, Virginia State Penitentiary began operating in 1800. Though it originally consisted of a single semicircular building, as time went on, the facility expanded as new buildings were added. Its long operation and central role in the state system made it a focal point of incarceration policy in Virginia, but at one point, it also gained the reputation of being "the most shameful prison in America."

Living conditions here were reportedly horrific, brought about by problematic infrastructure and eventually exacerbated by overcrowding. Windowless cell doors made it impossible to monitor inmates without opening the doors, which in turn gave them opportunities to riot, attempt to escape, or simply attack their jailers. It was also reportedly easy to smuggle banned products in and out of the prison due to the initial absence of an exterior wall. From December to February, the weather would become unbearably cold for the inmates because the penitentiary lacked a proper heating system. Worst of all, because the prison didn't have indoor plumbing, a nearby pond served as a communal dump where the inmates poured bucketfuls of their excreta. The accumulated filth meant steamy, stinky summers.

When the state installed an electric chair in the prison in 1908, it marked the end of executions by hanging in Virginia. A total of 247 prisoners (only one of whom was female) were executed in the penitentiary. The facility operated for nearly two centuries, surviving an earthquake and four fires before it was finally decommissioned and torn down in 1991.

Sing Sing

Following Auburn's Congregate System, Sing Sing opened in 1828. The New York prison is now so infamous, the town it was named after was eventually renamed Ossining to distance itself from the facility's unsavory reputation. Interestingly, it was built by the hands of prisoners transported from Auburn, the same inmates who would eventually occupy its cells. The site's construction was a three-year endeavor of digging up and laying marble from a nearby quarry. The cells were cramped and puny (7 feet long and 3 feet wide) and were devoid of a sewage system.

Throughout the course of the 19th century, labor within Sing Sing shifted to a contract regime, with the facility employing hundreds of prisoners in industrial production. The prison's physical plant and policies produced crowding, rigid discipline, and limited prisoner autonomy, which was characteristic of Auburn-system facilities at the time. Likewise, solitary confinement (in dark cells, nicknamed "coolers") was used as a means to punish prisoners who stepped out of line.

But apart from its inhumane living and working conditions, Sing Sing's notoriety is truly built upon its role in the state's enforcement of capital punishment. From 1891 to 1963, within the walls of Sing Sing, New York carried out 614 executions by electric chair (the famous "Old Sparky"), holding the record for any single prison in the United States. Despite subsequent attempts at administrative reforms in the 20th century, Sing Sing remained a maximum-security facility with an execution function until the 1960s. At present, it continues to operate as the Sing Sing Correctional Facility.

Debtors' prisons

Debtors' prisons in the United States that operated in the 19th century were typically county or municipal facilities that confined people for civil debts, sometimes in spaces built or adapted specifically for that purpose. Some noteworthy examples include the Debtors' Apartment (or Debtor's Wing) at the Moyamensing Prison (aka Philadelphia County Prison) and the Accomack County Debtors' Prison in Virginia. Facilities varied, but purpose-built or adapted debtor spaces were common. At Moyamensing, the Debtors' Apartment was architecturally distinct and separately administered. Meanwhile, at smaller county seats such as Gloucester County, Virginia, debtors were housed apart from criminals, yet still subjected to typical prison routines and heavily limited movement.

These institutions were infamous because confinement could occur without a criminal conviction and could continue until a creditor was satisfied or a court intervened. Many jurisdictions required prisoners to pay "jail fees" or board, making release dependent on resources the debtor did not have. These facilities featured abysmal conditions: cramped rooms, poor sanitation leading to the spread of diseases, and inadequate food. At the core of the problem, of course, is how poverty is inadvertently criminalized by this system: If you are poor, locked in prison, and unable to pay what you owe, things can only get worse for you.

As reported by PLOS One, the public and the courts eventually deemed debtor's prisons to be "inhumane and ineffective institutions." Consequently, Congress abolished imprisonment for debt under federal law in 1832. Various jurisdictions in the United States phased out the practice over time (Virginia, for instance, stopped putting people in jail for debt by 1849).

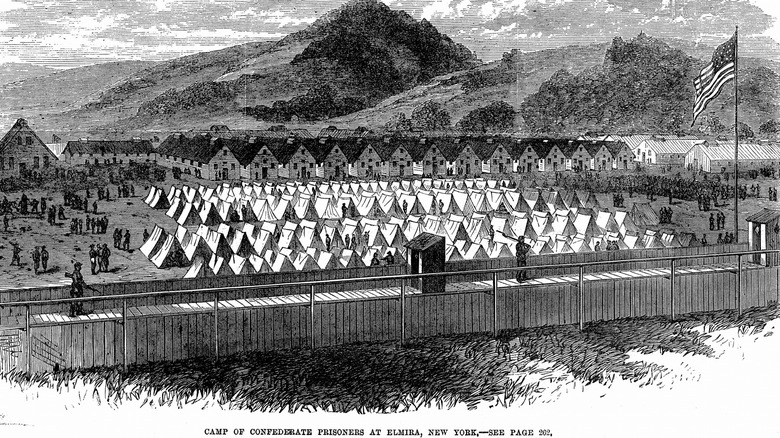

Elmira Prison Camp

Among the most messed-up things that happened during the American Civil War was the establishment of Elmira Prison Camp, a Union prisoner-of-war facility in what used to be military barracks along the Chemung River. Despite operating for just one year (from 1864 to 1865), it gained notoriety for having conditions so inhumane and a death rate so high that its unwilling denizens gave it the moniker "Hellmira." There were reportedly 12,122 Confederate prisoners kept within the confines of Elmira's four large camps, over 2,900 of whom died. That's a staggering 24% mortality rate, which no other POW camp in the North matched.

According to leadership's estimates, the existing structures could only hold 5,000 prisoners, yet it only took about two months for Elmira to be filled with nearly twice its capacity. The U.S. Army spent six months constructing additional barracks to safely house all the prisoners. As a temporary solution to the immense overcrowding at "Hellmira," many inmates found themselves staying in tents — in the harsh cold of the winter months. Unfortunately, it turned out to be "especially cold" that year, per the Army Medical Department Center of History and Heritage. I

In many cases, if the ferocious frost didn't cause the deaths of the Confederate prisoners, it was hunger, infectious diseases, and floodwater from the Chemung that did them in. Factor in the abysmal sanitation system in place, and it's no wonder that the death toll reached such astonishing numbers. The bodies were later buried in Woodlawn Cemetery alongside 119 Union soldiers.

Chain gangs

In 19th-century American prisons, groups of incarcerated people were physically restrained, typically by ankle chains, while forced to do outdoor labor (e.g., farm work, building roads, digging ditches). The practice of putting these so-called "chain gangs" to work expanded in the South after the Civil War as states and counties used prisoner labor to build and maintain public roads and other works under strict discipline and surveillance. In North Carolina, the law authorized counties to establish chain gangs. Prisoners doing time for petty larceny and vagrancy, as well as healthy male prisoners sentenced to up to 10 years, were commonly assigned to participate in these groups.

The system gained support because it was regarded as a two-in-one solution: Chain gangs provided the necessary manpower to complete public projects without additional expenses while also supposedly contributing to the process of criminal rehabilitation through hard labor. Unfortunately, this also exposed the chain gang members, many of whom were Black, to harsh weather conditions and even worse sanitation systems. They were even forced to sleep in cages while having to endure severe infections around their ankles (as their metal shackles constantly ground against their skin). Even as the prisoners got sick from enduring the elements, they received only the barest minimum of healthcare and food. They were also forced to work at gunpoint and punished with whipping for slacking off. It would take almost a century after the Civil War for this brutal practice to be abolished across all states.

Convict leasing

Under convict leasing, states and counties leased prisoners to private companies. The leased workforce, which was overwhelmingly Black, was subjected to involuntary servitude under contracts between the government and their lessees. Most of these businesses had been severely impacted by the Civil War (e.g., cotton plantations, railroads, and mines). This system was facilitated and even encouraged in Southern states by Jim Crow laws that led to many Black people being arrested for various minor offenses. It proved profitable for the states: Tennessee's convict leasing contracts contributed 10% of its state budget, while Georgia reportedly made over $35,000 within just a year and a half of implementing the system.

In essence, though, it was slavery without explicitly calling it slavery. Aside from being forced to work unreasonably long hours, they also had to survive starvation, dangerous weather conditions, and corporal punishment. Many were abused and tortured, to the point of exhaustion and even death. By 1870, over 40% of prisoners from Alabama had worked themselves to death after being leased to mining camps. Overall, between 16% and 25% of leased convicts reportedly died every year. Tragically, this system may have even contributed to one of the largest mass graves ever discovered.

The system was eventually abolished throughout the United States, with Alabama officially being the last state to do so, in 1928. Still, the horrible, uncomfortable reality remains: Convict leasing served as the foundation upon which many buildings, roads, and infrastructure components in the country were built.

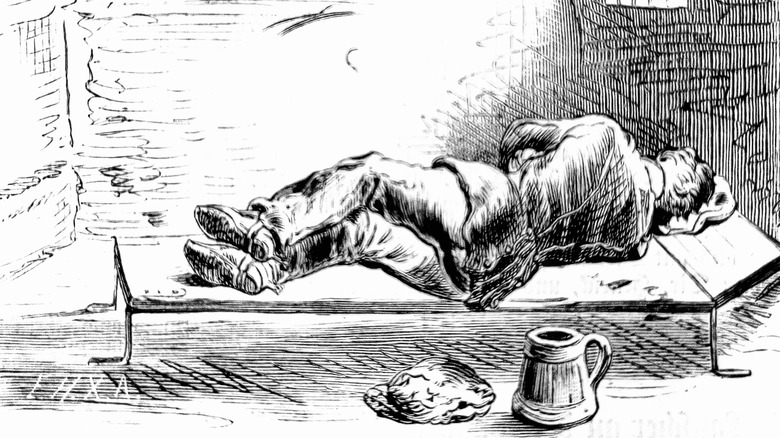

Food and malnutrition in American prisons

Since prisons in the United States were patterned after English prisons, both systems had similar approaches to feeding inmates. As British activist Michael Davitt once reflected after getting a taste (pun intended) of the typical diet in Portland Prison (per Medical History): "There is no bodily punishment more cruel than hunger ... that remorseless, gnawing, human feeling which tortures the mind in thinking of the sufferings of the body." Inmates were said to have received only bread and water as punishment for ill behavior, with meat and cheese serving as "rewards" for being subservient. As we mentioned, it's also common knowledge that prisoners forced into labor (such as those in chain gangs or leased convicts) or held in camps (such as Elmira's prisoners of war) did not receive adequate nutrition.

But even prisoners who simply stayed in their cells didn't have access to a particularly nutritious or adequate menu. Per the "Encyclopedia of Prisons and Correctional Facilities," 19th-century records from Philadelphia's Eastern State Penitentiary show that inmates' morning meals consisted of "a mix of bread and Indian mush" and a cup of either cocoa, coffee, or green tea. For lunch, inmates ate boiled meat, soup, some carbohydrates, and tea. Supper was just Indian mush and tea.

A curious detail about prison diets in 19th-century America: What we now regard as a premium and expensive food — lobster — used to be treated as nothing more than garbage food, suited only for the dregs of society. This so-called "poor people's food" was reportedly served to American inmates, enslaved peoples, and servants from the 1700s to the end of the 1800s.

Diseases in American prisons

If one were to cram a large group of people in an enclosed and heavily restricted space — particularly one with poor ventilation systems and even more abysmal sanitation and waste disposal facilities — the natural outcome would be for all sorts of infectious diseases to run rampant among the captive population. And that's exactly what happened in 19th-century American penitentiaries and prison camps. According to data from the mid-1800s, each year, tuberculosis (TB) accounted for more than 10% of all inmate deaths in the penitentiaries of states like New York and Philadelphia, as well as in Auburn Prison. In Minnesota State Prison, TB caused 35% of all mortalities from 1883 to 1835.

Citywide disease outbreaks eventually reached and penetrated prisons, too. The United States suffered major cholera epidemics in 1832, 1849, and 1866, and inmates behind prison walls weren't spared. One prison in Philadelphia appeared to have been hit hard enough by cholera that in order to curb its spread among inmates, desperate authorities decided that it was necessary to release prisoners who had only committed minor crimes. (Of course, this inadvertently gave them the means to become vectors of the disease in neighboring counties, so maybe not the best idea.) Meanwhile, in military prison camps in the 19th and 20th centuries, "gastrointestinal mortality" — deaths due to gastrointestinal infections, diarrhea, dysentery, and other food- and sanitation-related diseases — were deemed responsible for up to a staggering 33% of inmate deaths.

Devil's Island: France's most infamous penal colony

Located off the coast of French Guiana, Devil's Island was established as a penal colony in 1852, under the orders of Emperor Napoleon III. It was intended to relieve overcrowding in French prisons and to deter crime through harsh punishment. Eventually, it gained notoriety as one of the most brutal penal colonies of its time. The island itself was reserved primarily for high-profile and political prisoners (like Captain Alfred Dreyfus, a French officer who was falsely accused of treason in 1894). Other criminals, including repeat offenders and serious criminals, were confined on the neighboring islands or on the mainland.

The tropical climate, isolation, and inadequate facilities contributed to dire living conditions and were said to have killed thousands of inmates. Mosquito-borne diseases like malaria and yellow fever also led to many prisoner deaths. Food rations were poor in both quality and quantity, contributing to malnutrition and weakness. Medical care was minimal, and punishments such as solitary confinement were used extensively by reportedly sadistic guards. Prisoners often had to build infrastructure, clear land, and perform other extremely exhausting manual tasks in extreme heat. Escape attempts were nearly always unsuccessful because of the strong currents, sharks, and the remoteness of the islands. The penal colony operated until 1953, receiving between 50,000 and 80,000 prisoners throughout its lifetime.

If you're still interested, read on about what it's like inside the world's toughest prisons.