The Horrors Of B-17 Combat In WWII

Today, the B-17 bomber is regarded as a legendary aircraft of World War II. From its development and manufacture, which sometimes included building a fake town atop a Boeing plant, to taking to the skies, it was meant to be a long-range, high-altitude heavy bomber that inflicted major damage on Axis targets during daytime runs. Its four turbocharged engines were nothing to sniff at, and neither was its armament, ranging from the bombs in its bays to the multiple gunners that took position aboard each plane. The first prototype came about in the 1930s, though by the time the U.S. entered the war in December 1941, the craft was on its B-17E iteration (more are likely familiar with the B-17G).

However, while the B-17 was often called the "Flying Fortress" and gained a reputation for surviving heavy fire (including helping save the life of Dallas Cowboy Legend Tom Landry), serving on one wasn't easy. Other sources indicate that only 36% of crew members completed their required tour of 25 missions. The 100th Bomb Group, also called the Bloody Hundredth, was known to lose 12 or more planes on missions. During these bombing runs, planes would face German aircraft — including the Messerschmitt Me 262, the world's first jet fighter used in wartime — and ground-based flak guns blasting shrapnel-loaded shells miles upward. Even when a B-17 crew wasn't facing enemy fire, they still had to deal with the harsh conditions of flying a largely unpressurized high-altitude plane for long-range bombing missions.

B-17 planes could get incredibly cold

The B-17 plane was meant to be a high-altitude bomber, but it was only somewhat insulated in particular sections of the aircraft and not at all pressurized in the fuselage. For a lower-flying craft, that might have been manageable, but the B-17 was meant to climb up to around 30,000 feet in altitude, where temperatures plummeted to a frosty -60 to -70 degrees Fahrenheit. In short, parts of the airplane could turn into a miserable icebox, and that was before combat started. Lester Schrenk, a ball turret gunner, told the American Veterans Center that "luckily, I came from a farm and I was very used to the cold weather," unlike some other crewmates.

Of course, turning the crew into icicles wasn't part of the mission, so there were some solutions. Electrically-heated flight suits — often referred to as the "Blue Bunny" suit — kept crew members from freezing outright, though some noted that this could have the ironic effect of overheating and leaving an airman unpleasantly drenched in sweat. Still, it was better than nothing, so crew donned multiple layers of gear to survive, plugging heated suits into electrical outlets throughout the plane. Eventually, these had controllable temperature settings to get the heated flight suits within a reasonable range. However, Schrenk noted that sometimes the heated flight suits would still burn out and stop working — an especially tough proposition on the longest-term flights that could stretch out 12 hours or more.

B-17 crews wore oxygen masks to survive

Because the B-17 was unpressurized, oxygen levels within the plane could get dangerously low. To avoid the deadly lack of oxygen that could lead to hypoxia and anoxia, crews donned oxygen masks — and very definitely had to keep them on, never mind what later movies may have you believe. Unlike Axis air crews that used high-pressure oxygen cylinders, Allied B-17 bombers and other high-altitude craft used low-pressure systems that were far less likely to dramatically rupture if hit during an attack. Ultimately, they shifted over to on-demand systems that delivered oxygen when a user breathed in, increasing the efficiency of how oxygen was distributed over long missions. Crews had oxygen at their stations, in addition to "walkaround" bottles that allowed them to move around within the craft, as well as bail-out units meant to be used when the crew had to abandon their plane mid-air.

Veteran Harold Higgs told Veterans' Perspective that crews put on oxygen masks at around 10,000 to 12,000 feet in altitude. This was vital, he said, because going without supplemental oxygen at this point made it supremely difficult to think, a point that was dramatically illustrated on his first mission when a German Messerschmitt Me 262 attacked the plane on which he was serving as a co-pilot. The quick maneuvering and intense attacks brought about by the appearance of these early jet fighters demanded quick thinking, which would have been all but impossible with those oxygen tanks.

The structure of the plane increased risk somewhat

By the standards of the time, the B-17 was a serious technological achievement which, even if it didn't exactly make the Allies masters of the air, nevertheless gave them a serious leg up when it came to aerial attacks. It didn't become known as the Flying Fortress for nothing, after all. Yet, while many crew members spoke admiringly of their time flying the B-17 in comparison to other bombers, surviving the multiple missions required of each crew member was no easy task. Part of the considerable risk faced by the B-17 crew had to do with the very structure of the plane and other bombers, which had to balance the necessity of keeping things light and able to take to the skies, with the ability to also take sometimes dramatically heavy fire.

For one, the fuselage was fairly thin and made of a stressed skin duralumin, a lightweight aluminum alloy that was already common in airplane construction and which wasn't especially unique for bombers that had to climb to high altitudes. However, this may have been cold comfort for crew members facing the gunfire and flak shrapnel that could pierce the lightweight metal (that increased artillery power was one of the reasons WWII was much worse than WWI). Yet, it wasn't all bad. Duralumin was relatively strong for its weight, and the B-17 had an especially well-reinforced airframe that improved a crew's chances of making it out of heavy enemy fire.

The B-17 ball turret had some alarming details

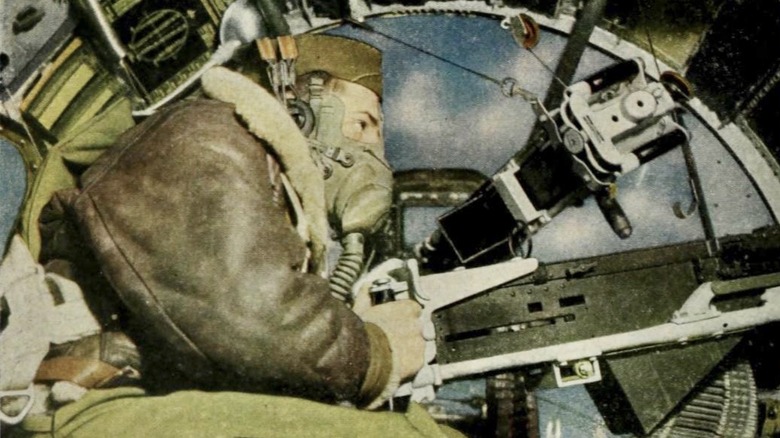

By the B-17G model's debut in mid-1943, the plane sported 13 machine guns and multiple turret positions. One of the most infamous may be the ball turret, which popped out of the belly of the plane. Wartime correspondent Andy Rooney claimed to have witnessed a B-17 landing in which a man stuck in a jammed ball turret was crushed, but this is now widely regarded as fiction (not least because the turret had a manual crank system that allowed for exit in the event of a failed mechanism, though in agonizingly slow fashion).

Still, the ball turret was intimidating. A gunner was crammed into a claustrophobic space that temporarily trapped them inside and made them dependent on waist gunners to bring them new oxygen canisters. William Carter, who served as a ball turret gunner in the 358th Squadron of the 303rd Bomb Group, said in an interview that the turret was only about 42 inches in diameter and packed full of equipment. Lester Schrenk, another ball turret gunner, noted that the crew member selected for this position was typically small ... but not always. He noted that he was nearly 6 feet tall and still had to get into one. Perhaps it was because he was the last selected for the crew, as he told the American Veterans Center. "Everybody else was afraid of it," he said. "I tried to give it away. Nobody would take it, so I was stuck with it."

B-17s regularly came under heavy fire

It is perhaps no surprise that bombers like the B-17 were prime targets for defensive forces — hardly anyone is going to happily welcome a giant plane dropping bombs on their land — but that didn't lessen the peril of facing enemy fire. B-17 crews routinely came under heavy fire from a variety of sources, from ground-based flak guns to Luftwaffe planes that met them in the air. That last point was an especially difficult proposition, as planners had initially thought that the B-17 and similar high-altitude bombers moved too fast and high for enemy aircraft to catch up. That was proven deadly wrong, with some estimates showing that bomber crews in 1943 had an 8% loss rate, with losses on some missions climbing as high as 30%.

Allied air forces did have some defense against this heavy fire. B-17s on bombing missions typically flew in a tight formation known as a "combat box." Exactly how squadrons arranged themselves within that group varied as the war continued, but the general idea was that gunners aboard each craft could provide covering fire for nearby planes in their group. Eventually, these bombing groups grew to include Allied fighter jets, which could fly ahead of or with formations to provide suppressing fire. Some, like the P-51 Mustang, were capable of much the same long ranges achieved by the B-17, while older fighters tacked on extra fuel reserves to make it that much farther on escort missions.

Bailing out could be perilous

If a B-17 was compromised and looked ready to fall out of the sky, the crew did have the option of bailing out. But this was hardly easy. First, there was the matter of preparation. The pilot training manual for the B-17 urged crew commanders to make sure everyone had a parachute before takeoff, and that it was close at hand near their assigned position. If a pilot determined that a bailout was imminent, he was supposed to ring the alarm bell in a particular pattern, then release anything in the bomb bay, turn on the autopilot, and do his best to slow the plane and keep it level. Other crew members also had important tasks in what was surely a chaotic environment, including maintaining radio communications if possible and getting a handle on the craft's position. As commander, the pilot was meant to bail out last of all.

Of course, the harsh realities of war meant that crew members might be injured, parachutes could be torn to shreds or get caught on debris, and a plane could be spinning so intensely that centrifugal forces made it extremely difficult to exit. Even if someone got out, they had to time their parachute opening just right — too soon, and they would be floating too high in the atmosphere with not enough oxygen. Pulling the parachute ripcord too late was, of course, also a dire scenario. Thankfully, many at least escaped some of the worst ways to die in WW2.

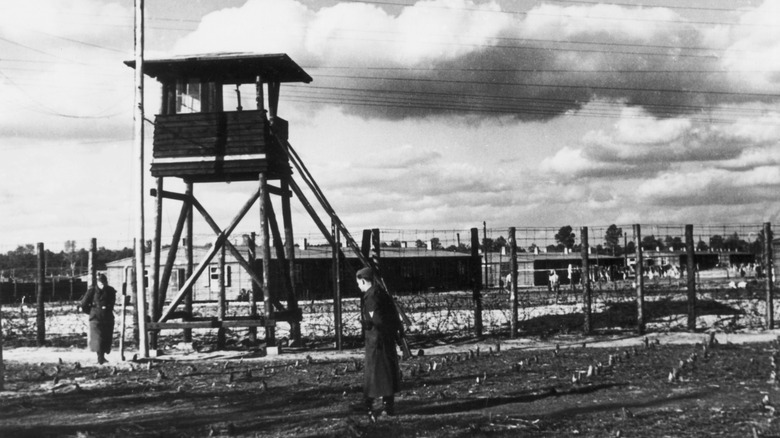

Crews that bailed out successfully still faced perils below

Bailing out of a B-17 could be terrifying, but multiple crew members successfully made it to the ground ... where they faced more danger, especially if they were deep into Axis territory. Donald Childes was one such B-17 pilot who survived a bailout above Germany. He was found, interrogated, then imprisoned in the Stalag Luft 1 P.O.W. camp. Another veteran who bailed out of a B-17, Lester Schrenk, told the American Veterans Center that not only was he interrogated, but he was threatened when he only gave his name, rank, and serial number. Confronted with a weapon and deadly threat ... Schrenk continued to give his name, rank, and serial number. Clearly, the interrogator was not ready to make good on his ultimatum.

Even if Nazis weren't waiting below, bailing out could still turn dire. J. Marvin Turner was part of a B-17 crew that went down after taking off from Italy. He and other crew members ditched, then climbed out of the quickly sinking plane into cold seawater, but some still didn't make it out of the rough, windy waves. The survivors waited for hours before rescue. Eddie Rickenbacker — who actually played a role in the naming of the first electric guitar — was part of another crew that crashed into the Pacific in October 1942, after losing their position and draining the fuel tanks. They floated in the vast ocean for an agonizing three weeks before U.S. Navy planes spotted them.

The bombing part of their missions made the plane vulnerable

Though B-17s often flew in tight formation in order to protect one another with covering fire, the part of the mission in which they actually released bombs opened crews up to further danger. In order for bombardiers to properly line up their targets and release bombs within an acceptable range, the B-17 was typically required to fly straight and level for minutes at a time — which could be an agonizing stretch with flak guns potentially below and fighter pilots nearby. Allan Packer, a fighter pilot who flew escort missions in P-51 and P-47 craft for B-17 bombers, noted that "they had to go in pretty much naked to the target" with little to no protection — though at least Packer and his fellow fighter pilots could provide protection at other times and by suppressing flak guns ahead of the bomber (via Veterans' Perspective).

This naturally made them easier pickings for fighters like the jet-powered Messerschmitt Me 262 craft used by the Luftwaffe. The issue became so bad that, for a time, B-17 bombing missions into the heart of Nazi-held territory ceased for a few months beginning in late 1943, until longer-range American fighter craft like the P-51 Mustang were ready to escort these extensive bomber missions.

Flak took down many planes

One of the greatest dangers faced by a B-17 and its crew was flak, the shrapnel-loaded rounds fired by 88mm guns on the ground below. Deployed against both tanks and airplanes, groups of these large flak guns lobbed 17-pound shells in rapid succession, sending shells into the range of bombers and exploding into thousands of fragments. Flak fire was frequently described by service members as one of the most frightening and routinely deadly perils they encountered. Shells could create widespread destruction that really skirted crew training and fighter escorts.

In response, B-17 crews wore flak suits that offered some protection against flying shrapnel. However, the steel plates in these padded suits could be cumbersome, weighing in at about 30 pounds. While it was certainly better than nothing, even these armor-like suits did not protect against all hits. One veteran waist gunner recalled that flak sent shrapnel directly through an open gun window in the fuselage, killing the gunner opposite him almost immediately.

Meanwhile, planes themselves remained vulnerable to flak, which could lead all too easily to downed craft if they encountered the telltale bursts of flak shells in the sky. J. Marvin Turner was an engineer on a 1944 flight out of Italy. Flak took out his B-17 so badly that the crew was forced to ditch the craft over the ocean. Turner and other crew members survived on a raft, but not all made it out of that mission.

Some personnel might have been in particular danger

Was there an especially bad place to be on a B-17? Maybe. Bombardier and navigator Robert Underhill told Veterans' Perspective that bombardiers appeared to be one of the harder-hit positions, perhaps because they were key personnel who were prime targets for enemy fighters. James Hubbell recalled one mission in which he flew with a tail gunner, saying, "I didn't ever want to go back there again [...] you could see this shooter up on the ground firing at you, and aiming at you, and you think you're going to get it right between the eyes" (via Imperial War Museums).

A 1944 study of battle casualties in the Eighth Air Force, conducted by Dr. Allan Palmer, seemed to suggest that waist gunners were hardest hit, but later analysis noted that Palmer could only collect data from June to August 1944 and mixed up statistics from B-17 and B-24 bombers. Moreover, he was only able to get that data from craft that returned, leading to survivorship bias that ignored key factors like what happened to lost craft. A closer look at the data completed by pilot and historian Kevin Michels suggests that all positions were close to one another in terms of risk, which could vary quite a lot over the course of the war. However, Michels did agree that waist gunners seemed to be consistently at the most risk, even if it wasn't dramatically worse than other positions on a B-17 (via 95th Bomb Group).

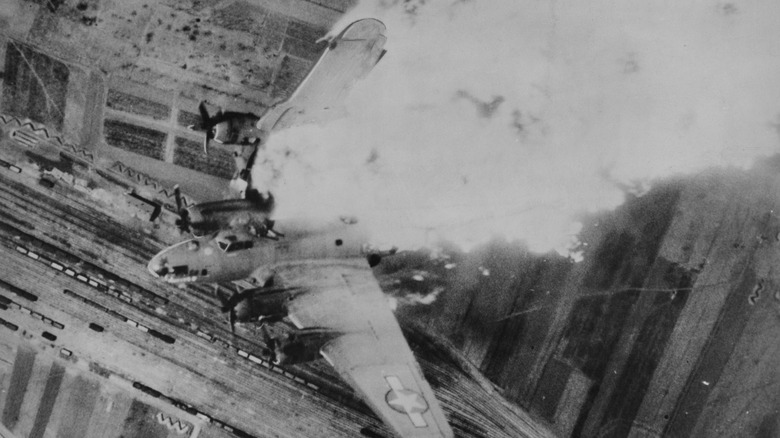

Damage from other Allied bombers was rare, but could be devastating

If a B-17 managed to face and survive the perils of enemy fire, there was still the problem of other Allied craft. Statistics indicate that friendly fire incidents typically happened in ground-based settings during the war and that air-based friendly fire was relatively rare. But when these incidents did happen, they could have disastrous consequences. Ironically, the combat box formation that provided some protection could prove deadly. The B-17G, known as the Miss Donna Mae II, was in just such a formation during a 1944 bombing run over Berlin. Somehow, it moved underneath another B-17 that was actively dropping bombs. As seen in a chilling series of photographs, one munition struck the Donna Mae's tail, sending the plane into a deadly spin that killed all 11 on board.

Multiple B-17s were also destroyed in mid-air collisions, including a February 1944 incident in which two bombers hit in the air above Reedham Marshes in Norfolk, England, resulting in 11 fatalities. A few months later, in July, a B-17 nicknamed "Little Boy Blue" crashed into a Suffolk field after mechanical issues caused it to fall back, where it then crossed into the path of another squadron. A different plane's propellers cut through Little Boy Blue's fuselage at about 15,000 feet; two crew members managed to parachute to safety, while eight more did not. Another pair of B-17s collided mid-air north of Berlin after a June 1944 mission, with 15 crew members dying. Five more survived but were captured and imprisoned by the Germans.