The Most Terrifying Structural Fires In History

There's no good way to die — the result is the same, regardless — but dying in a fire is a particularly horrible way to go: The intense heat, the smoke burning your lungs, the flames making escape impossible. The tales of survivors are always harrowing, and many escape with life-changing injuries.

There are plenty of places you might find yourself at the mercy of an inferno, but maybe none is scarier to think about than an enclosed structure like a hotel, a theatre, or a ship. While wildfires can burn for longer over much wider areas, resulting in higher death tolls, there is something about being trapped in a building that is quickly being engulfed in flames that is so terrifying it makes you want to thank every firefighter you meet.

But death toll doesn't always tell the whole story, and some tragic but less-deadly fires were the absolute worst to experience. Here are some of the most terrifying structural fires in history.

The Cocoanut Grove Nightclub, 1942

One of the most tragic nightclub fires in history happened in Boston on November 28, 1942. The Cocoanut Grove nightclub was hopping, filled to twice its capacity, when someone noticed a small fire in the basement lounge. One witness said it was so inconsequential that he was sure the club's employees could put it out. Then a decorative palm tree allowed the flame to climb up to the roof of the basement, which was set alight. From there, the fire spread unbelievably quickly. It didn't help that the club was using a flammable gas in its air conditioning unit due to shortages of Freon during World War II.

When the fire broke out, the electricity shorted, plunging the club into darkness. Panic ensued. U.S. Naval Reserve Lt. John Kip Edwards Jr. was in an upstairs lounge but managed to escape the blaze. He said of the disaster, "... it seemed that when the lights went out everybody's intellect went with them" (via the National Archives). The crush of people made it almost impossible to get out of the doors of the club. Soon, bodies piled up near the exits.

Luckily, a group of firefighters were just down the street dealing with a car fire, and were on the scene of the Cocoanut Grove inferno within minutes of it starting. But that brief period was all it took to cause utter devastation. Of the estimated 1,000 people in the establishment, 492 died, making it the deadliest nightclub incident in history.

The Bazar de la Charité, 1897

The Bazar de la Charité was one of the most exclusive events in Paris. The yearly charity bazaar was invitation-only, and at the May 4, 1897, event, dozens of aristocratic women and other notables crowded into a temporary wooden structure where 22 booths sold items whose proceeds went to charity. The honored guest that year was the Duchesse d'Alençon, sister of Empress Elisabeth of Austria, aka "Sissi."

The event was going well, with as many as 1,700 attendees spending money for a good cause. A presentation of a new invention, the cinema camera, was about to start. The projectionist needed more light when setting up, so his assistant struck a match. Somehow, this lit the very flammable building on fire, quickly followed by the equally flammable and voluminous clothing the society women were wearing. It took just 10 minutes for the whole structure to be engulfed in flames.

Of the estimated 125 people who were immediately killed in the blaze (with an unknown number later dying from their wounds), most were women. Many of the victims were burned beyond recognition, including the Duchesse d'Alençon. She and others had to be identified by their teeth, making this tragedy one of the first times dental records were used to identify victims.

The Station nightclub, 2003

On February 20, 2003, The Station nightclub in West Warwick, Rhode Island, was over capacity, with more than 420 people there to watch the band Great White. Disaster struck when pyrotechnics used during the band's performance ignited the acoustic foam around the stage, which was made from very flammable polyurethane. This set the whole ceiling alight within seconds. The situation was dire: the building had no sprinkler system.

Immediately, the carnage was obvious. "People were bleeding, their hair was being burned off, their skin was just melting off, skin was just dangling,” survivor Christopher Travis told The New York Times. "You could smell flesh burning even when I was inside." While the club had multiple exits, most people attempted to escape through the front door, resulting in a crush. Survivor George Guindon told the paper, "The flames were over my head, coming through the bar. I figure I had two choices: make a run for it or stay and die. I jumped over the bar and ran toward the wall, hoping I'd hit a window and not the wall. I ran across the street and into the snow. I looked back and saw people coming out. One guy, he already looked dead. He said, 'Don't touch me.' He had no face.”

The Station Nightclub fire (sometimes called the Great White Nightclub fire) killed 100 people.

King's Cross Underground Station, 1987

King's Cross tube station was one of the busiest stations in London, and on November 18, 1987, it was in the middle of rush hour when someone on one of the wooden escalators lit their cigarette, then dropped the match. The garbage and grease under the escalator were set alight, followed by the wooden escalator itself. Then came the huge fireball, shooting up into the ticket hall. The flames spread quickly due to the "trench effect," a phenomenon that wasn't even known about until this disaster.

Sgt. Sharon O'Neill of the British Transport Police was on duty that night. Years later, her still-vivid memories were shared on the BTP website: "When I got there, it was madness. It was too much to take in. ... On entering the booking hall of the fire with the fire service, I saw that the heat was so intense that concrete had cracked, tiles were stripped from the walls, and molten plastic was dripping from the handrails." The heat from the fire was so abnormally intense that firefighters had to spray not just the inferno with their hoses, but also each other, in order to withstand the temperatures for any period of time.

This was the first fatal fire in Underground history, and 31 people died. Burned beyond recognition, it took 16 years for the final victim to be identified.

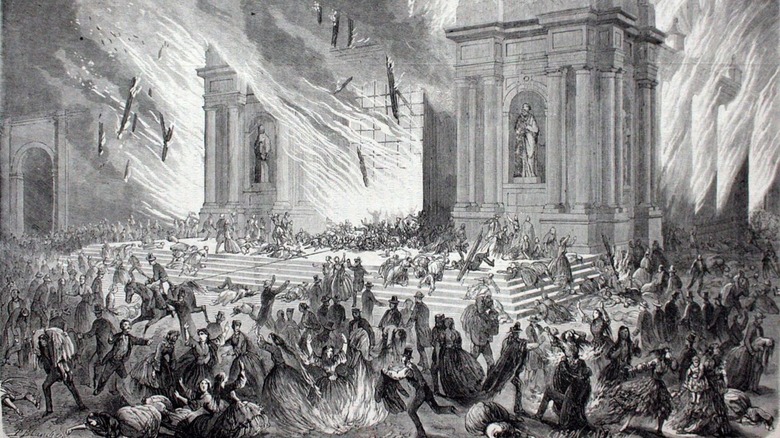

Iglesia de la Compañía Fire, 1863

On December 8, 1863, the Iglesia de la Compañía church in Santiago, Chile, was packed during an evening mass for an important date on the Catholic calendar, the Feast of the Immaculate Conception. The interior of the building was decorated in honor of the occasion, illuminated by oil lamps and candles. Suddenly, one of those lamps on the altar ignited something, possibly a hanging veil above it or paper flowers nearby.

The congregation, comprising more than 3,000 people, mostly women, panicked. They rushed to various exits, but the doors opened inward, making escape almost impossible, since the crush of terrified people didn't leave room to open them. Allegedly, the priests also closed one door behind them after they escaped, leading to more victims, while the holy men survived. There was no fire department to operate the water pumps and extinguish the flames; the pumps were not functioning properly in any case.

An estimated 2,000 to 3,000 people died. Because of anti-Catholic bias in much of the English-speaking world, reporting about the unfathomable tragedy often had more than a hit on victim-blaming. As one French publication put it, "some English papers, bellicose vipers of Protestantism, have the audacity to blame the clergy of Santiago" (via History Today).

The Winecoff Hotel, 1946

The Winecoff Hotel in Atlanta was supposedly fireproof, a reassuring thought to those who booked a room. Tragically, it was actually full of combustible materials, which caught fire on December 7, 1946.

The layout made the disaster even worse: there was only one staircase and no fire escapes, so everyone above the third floor (out of 15) was trapped by the fire. Open transom windows allowed oxygen to feed the flames. Assistant Fire Chief Fred Bowen told a local newspaper (via "Stories of the Winecoff Fire: A Dedication to the Memory of the 119" by Chet Wallace), "I don't know how many floors we went up. We went up so many of them because fire was all around the elevators. ... I saw so much I can't begin to tell you how horrible it was." Bowen was overcome by smoke and taken to a local hospital, where he begged to be allowed to go back and try to save people.

With the inferno still raging more than two hours after the firetrucks arrived, many people jumped to their deaths from the upper floors, desperate to escape the flames and smoke. E. J. "Chick" Hoach, an editor for the Associated Press who witnessed the fire, said, "I never expect to hear anything so terrible as the screams of those people from the time they would jump until they struck the pavement." Of the 280 guests and employees in the building, 119 people died, making it one of the deadliest hotel fires in history.

The Dabwali fire accident, 1995

On December 23, 1995, a tent erected in the courtyard of a building complex in Mandi Dabwali, India, caught fire during a school performance. The 1,500 people inside panicked, resulting in many victims being trampled to death in the rush to escape. Others were badly burned.

Local hospitals were overwhelmed and unable to provide even basic care to many victims. As one father, Vidya Sagar, told The New York Times, "For 90 minutes, my boy lay in the corridor, without first aid of any kind, and finally he died."

The final death toll is uncertain, with doubts cast on the official tally of 538 people, and locals believe up to 700 people died. Most of the victims were schoolchildren. The fact that children died while adults lived was shocking, with many appalled by the selfishness of the adults in placing their own safety over trying to help the young victims evacuate. Others disagreed. "It was too sudden for anybody to do anything," Mukesh Kamra told The New York Times. "Everything was over in five minutes. Nothing anybody could have done would have saved the children."

SS Morro Castle, 1934

The Chief Officer of the luxury ocean liner SS Morro Castle, William Warms, claims that the ship's captain, Robert Willmott, told him just hours before the disaster, "I'm afraid something is going to happen tonight, I can feel it" (via the Museum of New Jersey Maritime History). Something did happen to Willmott: he suddenly died of a heart attack. So, the ship, on its final day of a journey from Havana to New York City, was already in trouble when a fire broke out at around 3 a.m. on September 8, 1934.

The captainless-crew made several bad decisions once they were alerted to the fire, and the ship was quickly engulfed in flames. Rescue efforts were slow, and — like the Titanic disaster before it — the lifeboats were not filled to capacity, yet those in them distanced themselves from the burning ship, forcing many to jump into the ocean where they drowned. Some suffered even worse fates.

Gretchen F. Coyle and Deborah C. Whitcraft, the authors of "Inferno at Sea: Stories of Death and Survival Aboard the Morro Castle," found themselves talking to an 85-year-old woman whose brother, then aged 10, had died in the disaster, and she had never learned what happened. "We didn't want her to know how bad, how badly this little boy suffered," Whitcraft explained to Asbury Park Press. "... Because the truth is, he lived for several hours waiting for help, in salt water with third-degree burns. It had to be an excruciating death." Of the 550 people on board, 137 died.

Triangle Shirtwaist Factory, 1911

The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, which occurred on March 25, 1911, is one of the most infamous fires in history. Mary Domsky-Abrams worked on the ninth floor of the factory. Interviewed almost 50 years later, she explained who made up the workforce: "There were very few men in the shop; the hundreds of girls ... had [mostly] been in the country only a year or less. For many, as for me, it was only the second job; for others, the first that they had had. Most of us were not yet 20 years old" (via Cornell University).

The management did not want the women stealing things or taking unauthorized breaks, so all the doors were locked. When the fire started, this would prove fatal. Domsky-Abrams saw the inferno from the street. She remembered, "Flames poured through the windows of the top floors and thick smoke billowed. ... The screams and sobs all around were deafening. Water was being poured onto the flames, the firemen and police were doing their utmost, but they were not prepared for so overwhelming an emergency ..." She survived the disaster only because she defied her boss and left work five minutes early.

Others were not so lucky: 146 garment workers — mostly women and girls — died due to the fire. Many jumped to their deaths. The truth about the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire was so messed-up that the pubic was furious upon learning the details, and the tragedy led to some much-needed reforms.

Grenfell Tower, 2017

When a fire broke out in the 24-floor London apartment building, Grenfell Tower, on June 14, 2017, the devastating tragedy was caught on live TV. What started as a small fire in the kitchen of one flat quickly turned the entire building into a towering inferno. The danger was compounded by the emergency services' terrible decision to instruct residents not to try to evacuate but instead to shelter in place.

The resulting tragedy was heartbreaking and infuriating. "We learned of how whole families died huddled together in corridors, a mother found with her 6-month-old baby in the stairwell after having attempted to escape," resident Mohammed Rasoul told The New York Times. "... There was a stage where we were burying people every few days, months after the fire." The pain of the victims continued long after the blaze was extinguished. Hamid Wahabi lived on the 16th floor and was lucky to escape with his life. "I have flashbacks every single day, of the smoke, of people running out, of the tower in flames, lit like a giant candle," he told the paper.

A total of 72 people died in the fire. An inquiry found that many organizations and companies contributed to the disaster by lying about the safety of their products or ignoring the prescient concerns of residents. Many pointed out that most of the victims were poor people of color, and so had been considered unimportant by those in power.

PS General Slocum, 1904

A church group had chartered the pleasure steamboat PS General Slocum to take them along the East River of New York City on June 15, 1904. While the origin of the fire remains unknown, a massive blaze quickly engulfed the wooden ship.

Safety equipment had been neglected for years, making it almost impossible to pump water to put out the flames, and survivors claimed the life preservers crumbled as they put them on. In desperation, many jumped into the river, where they drowned. One of the stories in "New York's Awful Excursion Boat Horror Told By Survivors and Rescuers" records, "It was a spectacle of horror beyond words to express — a great vessel all in flames ... within sight of the crowded city, while her helpless, screaming hundreds were roasted alive or swallowed up in the waves — women and children with their hair and clothing on fire; crazed mothers casting their babies overboard or leaping with them to certain death ..."

It was one of the biggest disasters in American history that people have somehow forgotten about, but, as a letter to The New York Times pointed out, it was immortalized in the classic James Joyce novel "Ulysses," where a character says, "Terrible affair that General Slocum explosion. Terrible, terrible! A thousand casualties. And heartrending scenes. Men trampling down women and children. Most brutal thing." Of the 1,388 people on the boat, 957 died, most of them women and children.

The Iroquois Theatre, 1903

By the time 1903 rolled around, people were very aware that huge, deadly fires could kill dozens of people in public buildings very quickly. So when the Iroquois Theatre in Chicago was built, one of the draws it used to attract customers was that it was "fireproof." In reality, corners had been cut, and local officials in Chicago, who were aware of this, had looked the other way.

On December 30, more than 1,700 people were crowded into the theatre (this number didn't include standing-room-only tickets for the people who filled the aisles). The act on stage was performing the song "In the Pale Moonlight," with the moon effect created by an arc lamp. But the lamp ignited a stage curtain, and the theatre was quickly ablaze. Actor Eddie Foy was offstage, and later recalled the reaction of patrons as a "mad, animal-like stampede — their screams, groans and snarls, the scuffle of thousands of feet and bodies grinding against bodies merging into a crescendo half-wail, half-roar" (via Smithsonian Magazine). There was a crush on the staircase as people tried to flee; the exit doors opened inward, making escape more difficult, and when a stage door was opened, the rush of air caused a fireball, killing many instantly.

The fire left 602 dead, making it the deadliest single-building disaster in the U.S. until 9/11. Most of the victims were women and children. The lamp that ignited the fire, twisted and burned, is on display at the Chicago History Museum.