The Most Infamous Events Of The Vietnam War

The U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War was so controversial that one could argue it was really just a string of horrible events, each one more infamous than the last. But even in a packed field, where bad decisions were followed by tragedy over and over again for years, in a war that almost everyone could see was unwinnable, there are still a handful of moments that stand out as the worst of the worst.

Some of the worst incidents were not on the battlefield or even in Vietnam. The murder of four students at Kent State by National Guard members is still well-known as one of the low points surrounding the war. However, there are enough controversial events that took place directly as a part of the war itself that more tangentially related events are not even necessary to understand just how many disastrous moments resulted from U.S. involvement in Southeast Asia.

Spanning more than a decade and resulting in the deaths of an unforgivable number of people, these were some of the most infamous events of the Vietnam War.

The assassination of Ngo Dinh Diem

The U.S. had already been interfering in Vietnam for years before sending combat troops in the mid-1960s. The U.S. helped install Ngo Dinh Diem (pictured) as the leader of South Vietnam in 1954, and didn't complain when he stayed in power through a blatantly rigged election. But in the early 1960s, America began to see the downsides of its support for Diem. Despite outwardly supporting him, John F. Kennedy's administration was furious that the devoutly Catholic Diem was violently suppressing the Buddhist population, which made up a majority of the country. And when Kennedy sent 11,000 troops to help train South Vietnamese forces, Diem pushed back, saying, "All these soldiers I never asked to come here. They don't even have passports" (via the Council on Foreign Relations).

So when the government learned of a possible coup plot forming against Diem, three members of the Kennedy Administration used the confusion of a holiday weekend to push through their agenda. On August 24, 1963, the U.S. Ambassador to South Vietnam received a telegram stating that "Ambassador and country team should urgently examine all possible alternative leadership and make detailed plans as to how we might bring about Diem's replacement if this should become necessary."

Despite many members of the administration disagreeing with this strategy, they eventually allowed the coup to go ahead — which became a big problem when the ousted president was violently assassinated along with his brother. The U.S. was now more embroiled than ever in Vietnam.

The Gulf of Tonkin Incident

In 1964, their limited attacks and intel-gathering missions into North Vietnam were going badly for the South Vietnamese, so the U.S. instructed them to change strategy. In order to help gather information that would make their new tactics more successful, the U.S. Navy planned secretive patrols in the Gulf of Tonkin during July 1964. On August 2, while on one of these patrols, the destroyer USS Maddox was attacked by three North Vietnamese boats; it destroyed one and heavily damaged the others. Then, two days later, both the Maddox and the USS Turner Joy were attacked again in what would become known as the Gulf of Tonkin incident.

The only problem is that the Gulf of Tonkin Incident didn't happen. According to the U.S. Naval Institute, Commander James Stockdale would later report, "I had the best seat in the house to watch that event and our destroyers were just shooting at phantom targets — there were no PT boats there ... there was nothing there but black water and American firepower." The North Vietnamese "boats" that night only existed in a confused radar reader's head.

Despite the reality of the situation, reports of two U.S. ships being attacked by Viet Cong boats allowed President Lyndon B. Johnson to bring the U.S. into the Vietnam War in a much bigger way. While the American public wouldn't have evidence they were duped for decades, even at the time, the decision to send in more troops over the seemingly minor incident was controversial.

The Hanoi March

On July 6, 1966, around 52 U.S. POWs were paraded through the streets of Hanoi, with the Viet Cong recording the whole thing in hopes of getting international sympathy.

At first, the blindfolded men had no idea what was happening or why they had been transported from their prison camps. In a 2019 interview with The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training, General Charles Graham Boyd (then a fighter pilot who had recently been shot down and captured), recalled, "As we emerged onto a major street our blindfolds were pulled off, and we saw, and heard, literally thousands of Vietnamese screaming, all agitated by men in civilian clothes with bullhorns ... encouraging the angry crowd to show us how unwelcome we were in their country. At that moment of blindfold removal, I saw a guy I knew who had been declared KIA a year earlier, and heard him say, 'Oh boy, a parade, I love a parade.' With that wonderful little slice of fighter-pilot panache, the parade began."

Over the course of an hour, the POWs were marched two miles. Along the way, they were repeatedly attacked and beaten, with the intensity increasing until a full-scale riot broke out. By the time the "parade" ended, almost every POW was injured, with the men suffering everything from loose teeth to broken noses to a partial hernia, but they were lucky no one was killed. The footage horrified the international community, and the treatment of POWs became an important talking point in the anti-war effort.

The Tet Offensive

For the United States, the Tet Offensive was the turning point in the Vietnam War that changed everything. On January 30, 1968, the North Vietnamese launched a coordinated series of guerrilla attacks meant to destabilize the South Vietnamese government and encourage defection. The Viet Cong even managed to launch attacks on the U.S embassy in Saigon, deep inside South Vietnam's territory.

Which side emerged victorious from Tet depends on who you ask and what you think "winning" looks like. The North Vietnamese sustained heavy losses, with between 30,000 and 50,000 casualties. They gained no ground and were pushed out of every location they targeted. However, simply mounting such a bold and coordinated attack in the first place was a win for the North Vietnamese. The U.S. public was shocked that such an attack was possible, as it went against what pro-war politicians had been saying about the enemy's capabilities. When the U.S. government admitted after Tet that it would need to send more troops to the country, the public backlash was immediate.

A sign of just how badly the average American was now against the war was Walter Cronkite's frank assessment on the CBS Evening News broadcast of February 27, 1968 (via Digital History): "We have been too often disappointed by the optimism of the American leaders, both in Vietnam and Washington, to have faith any longer in the silver linings they find in the darkest clouds. ... To say that we are mired in stalemate seems the only realistic, yet unsatisfactory, conclusion."

My Lai Massacre

The My Lai Massacre occurred on March 16, 1968, when a U.S. battalion slaughtered more than 500 unarmed Vietnamese civilians, with many more maimed for life (pictured), and dozens raped. The majority of the victims were women, children, and the elderly.

There are many incredibly disturbing firsthand accounts from the survivors of the My Lai Massacre, but it is not just the stories of the victims that prove what atrocities were committed, however. Several servicemen also admitted what they did that day. According to The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, one soldier later described his horrific actions: "We just rounded 'em up, me and a couple of guys, just put the M-16 on automatic, and just mowed 'em down." Private Paul Meadlo said something very similar when he gave an infamous interview to CBS News in 1969, admitting, "I might have killed 10 or 15 of them. ... Men, women, and children. ... And babies." He said it was mostly done out of frustration and revenge.

The massacre finally stopped when American Warrant Officer Hugh Thompson saw what was happening as he flew over My Lai in his helicopter. Landing, he instructed some of his men to protect a group of Vietnamese civilians, even if it meant shooting fellow U.S. soldiers. Despite the violent murder of hundreds of civilians, the U.S. military initially claimed only combatants had been killed. It would be more than 18 months before the public would learn what really happened at My Lai.

The Green Beret Affair

The original Special Forces, often called the Green Berets, have many strict rules they have to follow. That doesn't mean that things don't sometimes go wrong, even with what are supposed to be some of the most disciplined troops in the U.S. military. The Green Beret Affair was one such incident.

The CIA was heavily involved in the Vietnam War and worked alongside the Special Forces on Project GAMMA, which involved handling Vietnamese spies. When the CIA suspected one of their double agents, Thai Khac Chuyen, was actually a triple agent, they allegedly encouraged the Special Forces unit to take care of the problem. On June 20, 1969, Chuyen was taken on a boat into the South China Sea where he was chained, shot, and thrown overboard.

The soldiers involved were charged, but the trial collapsed when the CIA refused to let any of their employees testify. Still, the event shook many of those in similar situations. Jeff Stein, who was in charge of a military intelligence operation at the same time as the story was breaking, wrote later about the position it put him in when one of his agents failed a polygraph test: "Would I kill my own spy, I wondered, if it turned out he was working on the other side, if the lives of all my other agents were thrown into jeopardy? ... Such were the perilous currents of Viet politics that a 22-year-old college dropout, as I was then, was supposed to fathom" (via Vietnam Generation Journal).

Operation Breakfast

Despite the Nixon Administration publicly supporting both Cambodia's government and its neutrality in the Vietnam War, Henry Kissinger felt it was necessary to bomb the country in order to disrupt North Vietnamese supply lines. He pushed hard for the U.S. to secretly carpet bomb the country, using acknowledged bombings across the border in Vietnam as cover for the plan.

Kissinger got his way, and the extremely top-secret mission was dubbed Operation Breakfast. In his diary entry for March 17, 1969 (via The Progressive Magazine), H.R. Haldeman wrote, "Historic day. [Kissinger]'s 'Operation Breakfast' finally came off at 2:00 p.m. our time. [Kissinger] really excited, as is [Nixon]." The following day's entry said, "[Kissinger]'s 'Operation Breakfast' a great success. He came beaming in with the report, very productive."

Hundreds of thousands of Cambodians died over the course of the operation, with the longer four-year bombing campaign dubbed Operation Menu. (This was one of the reasons why Henry Kissinger's Nobel Peace Prize was so controversial.) The cluster bombs Kissinger fought so hard to drop on the neutral nation are still causing problems to this day, with an estimated tens of thousands of people being killed or maimed in the decades since the war when they are unlucky enough to come across an unexploded, but still primed, ordinance.

The secret invasion of Cambodia

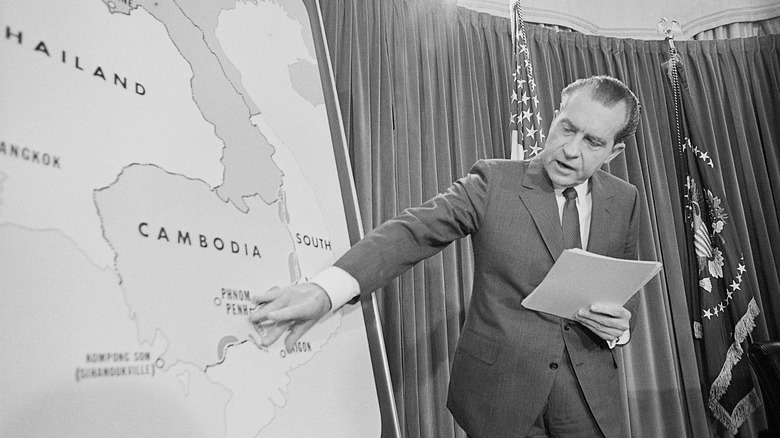

A year after Operation Breakfast, President Richard Nixon ordered troops into Cambodia for the first time on April 28, 1970. This development was so secret that many of his most important advisors didn't know about it until after it happened. The decision was controversial even among those who knew, to the point that Henry Kissinger encouraged Nixon to reconsider. Kissinger would later record that a frustrated Nixon, often drunk and feeling bullied by Congress, was determined.

The decision would prove disastrous in many ways. While directly responsible for the deaths of Cambodians, indirectly, both the infantry attacks and the bombing campaign would lead to millions of deaths by helping the Khmer Rouge become more powerful in the country. According to New York Times correspondent Sydney Schanberg (via Frontline), the Khmer Rouge "... would point ... at the bombs falling from B-52s as something they had to oppose if they were going to have freedom. And it became a recruiting tool until they grew to a fierce, indefatigable guerrilla army."

When the public learned about the invasion two days later, Nixon went on TV to explain why he made the decision (pictured), but despite his 2,700-word address to the nation, the public was furious. Protests against this escalation of the Vietnam War took place across the country, including on the campus of Kent State. It was this event that the unarmed students were protesting when they were shot by the National Guard.

Operation Ivory Coast

On November 21, 1970, U.S. Special Forces launched Operation Ivory Coast. The soldiers involved had been training for months, until they had everything they needed to do to rescue more than 60 POWs from the Son Tay prison camp in a heavily guarded area of North Vietnam and make it out alive down to the minute. This meticulously planned and audacious rescue attempt went off perfectly ... almost.

Captain Richard J. Meadows led the team of 14 men. According to the U.S. Army, when they breached the compound, amplified by a bullhorn, Meadows announced, "We are Americans, this is a rescue, keep your heads down, we are here to get you out." However, he was only met with silence. An hour later, the team was headed home. In many ways, Operation Ivory Coast is considered an example of a perfectly executed mission — except for the fact that no POWs were rescued, as they had been moved to a different camp months before.

Trying to explain this disastrous intelligence failure, Secretary of Defense Melvin R. Laird lamely stated during a congressional hearing that "no camera has ever been constructed that can see through the roofs of buildings." The embarrassing debacle resulted in a complete overhaul of the U.S. Intelligence Community the following year.

The Fall of Saigon

The Vietnam War had obviously been unwinnable for years, but American troops only officially withdrew from the fighting after the Paris Peace Accords in May 1973. The conflict between North and South Vietnam would continue, and it was another two years before the North managed to invade the South's capital of Saigon.

For the United States, the complete Vietnam War timeline ends with the Fall of Saigon, beginning on April 29, 1975. That day, Armed Forces Radio broadcast the statement "The temperature in Saigon is 105 degrees and rising," followed by Bing Crosby's "I'm Dreaming of a White Christmas" on repeat. This was the signal for any Americans left in the city to evacuate. An estimated 10,000 South Vietnamese citizens also lined up outside the U.S. embassy, hoping to escape. The evacuation involved 81 helicopters, with one landing at the embassy every 10 minutes for 19 hours (pictured). Thousands managed to flee, but many more who wanted a spot on a chopper out of Saigon didn't get one.

U.S. diplomat Wolfgang J. Lehmann was on one of the final helicopters. He later wrote (via the National Museum of American Diplomacy), "We could see the lights of the North Vietnamese convoys approaching the city. ... The chopper was packed... and it was utterly silent except for the rotors of the engine. I don't think I said a word on the way out, and I don't think anybody else did. The prevailing emotion was tremendous sadness."