The Meaning Behind Paul McCartney's Darkest Songs

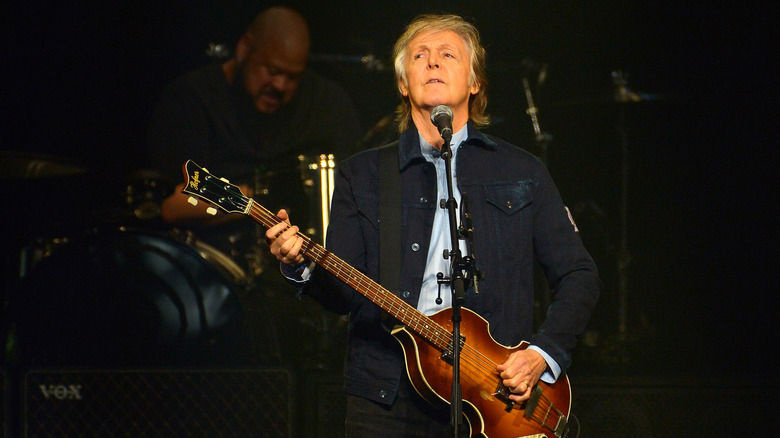

The story of Paul McCartney is one of a songwriter, first and foremost. Since the 1950s, he's been composing music and lyrics, most famously as a member of the Beatles. But he was also the frontman for Wings, one of the most important rock bands of the 1970s, and is one of the most successful solo artists of all time. A multi-instrumentalist with one of the most expressive and recognizable voices in rock history, McCartney is among the handful of modern pop's true architects.

While his art has made him fabulously wealthy — the kind of person who has a staff that must follow strict rules — McCartney has also lived a remarkable life, professionally and personally. The Beatles' story is a tragic one, and McCartney's life is full of sad details, too. His compositions are generally optimistic, but they sometimes get moody, reflective, negative, and ominous. Out of the hundreds of songs McCartney has written, a dozen stand out as particularly daring, troubling, and unsettling. Here are the true tales behind the darkest songs in the Paul McCartney canon.

Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)

Paul McCartney's track "Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)" was released on 1965's "Rubber Soul." Technically considered a rock song because it was recorded by The Beatles, "Norwegian Wood" sounds more like a very old folk tune or sea shanty but also benefits from the addition of the sitar. It's one of the first times the Asian instrument appeared on a Western rock song, as played by Georgie Harrison. The rest of the track was written mostly by John Lennon, but Paul McCartney helped come up with the concept and compose big chunks of the piece.

John Lennon had written the first, innuendo-laced first line — "I once had a girl, or should I say, she once had me" — of the song. McCartney took it from there, theorizing that the song was about a tryst set in the mid-1960s when cheap wood furnishings were a big fad. "A lot of people were decorating their places in wood," McCartney explained in "Paul McCartney: Many Years from Now." "Norwegian wood. It was pine really, cheap pine," So it was a little parody really on those kind of girls who when you'd go to their flat there would be a lot of Norwegian wood."

It was also McCartney's idea to give the song a violent twist. "So she makes him sleep in the bath and then finally in the last verse I had this idea to set the Norwegian wood on fire as revenge, so we did it very tongue in cheek" he said.

Maxwell's Silver Hammer

On the tightly constructed 1967 concept album of story songs that is "Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band," Beatles co-leader Paul McCartney contributed a sing-songy tune that sounds more at place on a vaudeville stage or a British music hall than it does on a progressive album by one of the most important rock bands of the 1960s. But a close listen proves it's just as provocative, if not more so, than the other progressive rock of the era. Particularly "Maxwell's Silver Hammer," which concerns the exploits of medical student Maxwell Edison, who, in succession, bludgeons to death (with his titular implement) a classmate, a teacher, and the judge presiding over his trial.

A song that glibly and gleefully runs through multiple violent murders is superficially dark enough, but the emotional truth of "Maxwell's Silver Hammer" is somehow even bleaker. "Some of my songs are based on personal experience, but my style is to veil it," McCartney said in "The Beatles Anthology." He later explained: "The song epitomizes the downfalls of life. Just when everything is going smoothly — Bang! Bang! — down comes Maxwell's silver hammer and ruins everything."

Eleanor Rigby

The opening lyric of "Eleanor Rigby" — "look at all the lonely people" — gives fair warning that it's going to be a sad song. The first track on the 1966 Beatles album "Revolver" concerns lonely Eleanor Rigby, who engages in such painfully solo activities like cleaning up a church, and Father McKenzie, who writes undelivered sermons and mends his socks late at night. Eventually, the two meet: When Father McKenzie presides over Eleanor Rigby's burial.

John Lennon and Paul McCartney both wrote a sizable part of the song, with McCartney taking inspiration from an older woman he befriended when he was a child living in a low-income housing complex. "I had that figure in my mind of a sort of lonely old lady, and over the years I'd met a couple others, and I don't know, maybe the loneliness made me sort of empathize with them," he told GQ. " But I thought it was a great character. So I started this song about a lonely old lady who picks up the rice in the church, who never really gets the dreams in her life, and then I added in the priest." For the titular character's name, McCartney got "Eleanor" from "Help!" co-star Eleanor Bron, extended to fit the lyrical cadences, and saw "Rigby" on a storefront in Bristol. Later, McCartney learned that in the same area where he and Lennon once lived, the local graveyard contained a tombstone marking the burial spot of a real Eleanor Rigby.

She's Leaving Home

The Beatles' best-known song that details a day in the life is 1967's "A Day in the Life" from "Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band." Another track on that same album, "She's Leaving Home," starts out the same way, with a third-person account of morning activities. Except this time, Paul McCartney's singing is melancholy, and the words aren't about the mundane — the story follows a young woman who runs away, to the confusion and heartbreak of her family.

At age 17, Melanie Coe, a regular in London's rock and dance club scene of the era, departed her parents' home, learned she was pregnant, and laid low at a friend's house until her parents found her and she ran off again. She was permanently located three weeks later. "I think my dad called up the newspapers — my picture was on the front pages," Coe told The Guardian. Elsewhere, McCartney explained the inspiration in "1000 U.K. Number One Hits." "We'd seen that story and it was my inspiration," he said. "There was a lot of these at the time and that was enough to give us the storyline." McCartney pulled straight from the headlines, starting the song with the main character quietly leaving home in the early morning after writing a goodbye note. "It was rather poignant," he said.

Blackbird

While it's officially a Beatles song and co-credited to John Lennon due to a music publishing agreement, "Blackbird" is in actuality a Paul McCartney solo joint. It's a standout for its simplicity and quietness on the Beatles' often loud, freewheeling, and experimental self-titled 1968 double LP (generally known as "The White Album"). Gentle but a little spooky, McCartney sings and plays the acoustic guitar — and that's the only instrument — on the song about a blackbird unable to fly but yearning to do so.

McCartney's actual inspiration and intent would be tough to guess from the lyric sheet. "I was sitting around with my acoustic guitar, and I'd heard about the civil rights troubles that were happening in the '60s in Alabama, Mississippi, Little Rock in particular," he told GQ. McCartney was referring to the Little Rock Nine: Black students in 1957 who became the first people of color to enroll at whites-only Little Rock Central High School after the Supreme Court's ruling on Brown v. The Board of Education legally ordered the end of school segregation in the United States. They faced heavy opposition, violence, and intimidation, and the Arkansas government tried to get the National Guard to prevent the entry of the Little Rock Nine. "I just thought it would be really good if I could write something that, if it ever reached any of the people going through those problems, it might kind of give them a little bit of hope," McCartney said. "So, I wrote 'Blackbird.'"

Another Day

The very first single bearing Paul McCartney's name after the contentious end of the Beatles: "Another Day." Unlike the chirpy, sunny compositions he brought to the Beatles throughout the band's many stages, "Another Day" was the spiritual successor of his earlier outlier "Eleanor Rigby." It, too, was about an overlooked woman going about a tedious day, as presented by an all-seeing narrator offering commentary and pity.

McCartney admits to showing off his creepy side in songs like "Eleanor Rigby" and "Another Day." "I suppose, basically, it's because I'm a voyeur," he told Rolling Stone. "Observing a woman rather than just being with her, thinking, 'Oh, I love that.' Drinking a cup of coffee, going to the office with her papers, all that — following her through her day." McCartney explained and justified further in "The Lyrics: 1956 to the Present." "Like many writers, I really am a bit of a voyeur; if there's a lit window and there's someone in it, I will watch them," he wrote. "Hands up, guilty. It's a very, very natural thing."

Too Many People

Following increasing tensions between John Lennon and Paul McCartney, the Beatles broke up in 1970. Almost immediately, the combatants aired their grievances. On this third solo album, 1971's "Ram," McCartney included the song "Too Many People," a snide and angry polemic that takes aim at self-proclaimed do-gooders who don't really seem to do very much good at all. Rumor had it that the song was a result of McCartney's then-adversarial relationship with his former bandmate. Lennon certainly thought it was about him. "I heard Paul's messages in 'Ram' — yes there are dear reader!" Lennon told Crawdaddy (via The Beatles Bible) after he responded to "Too Many People" with "How Do You Sleep," which is full of McCartney insults. "And since you've gone, you're just another day" is a teasing reference to McCartney's "Another Day," for example.

McCartney would later admit that "Too Many People" really was about Lennon, particularly the key lyric, "Too many people preaching practices." "He'd been doing a lot of preaching, and it got up my nose a little bit," he told Playboy (via Far Out). "This song was written a year or so after the Beatles breakup, at a time when John was firing missiles at me with his songs, and one or two of them were quite cruel," McCartney explained in "The Lyrics: 1956 to the Present." "I decided to turn my missiles on him too, but I'm not really that kind of a writer, so it was quite veiled," he later added.

Band on the Run

A multi-part miniature epic, "Band on the Run" boasts a lot of ambitious grandeur, which suits its plot. On the surface, the opening and title track from Paul McCartney and Wings' 1973 album is about a prison break juxtaposed with the life of a constantly touring rock band. It is a statement about law enforcement, but it takes a closer read to truly get what McCartney was trying to say.

"There were a lot of musicians at the time who'd come out of ordinary suburbs in the '60s and '70s and were getting busted," McCartney said in "Classic Rock Stories: The Stories Behind the Greatest Songs of All Time." "We were being outlawed for pot," he later added. "It put us on the wrong side of the law. And our argument on the title song was, 'Don't put us on the wrong side, you'll make us into criminals. We're not criminals, we don't want to be." On top of all that, McCartney came up with a framing device in the form of a prison breakout squad.

Tug of War

In 1982, Paul McCartney rolled out his second post-Wings album, the solo LP "Tug of War." It was also his first ever recorded without songwriting input from his wife, Linda McCartney. Left to his own devices, the album is often bittersweet if not somber, particularly on "Here Today," a remembrance of fellow Beatle John Lennon, assassinated in 1980. Then there's the title track, "Tug of War," which is a conflicted and layered examination of both the endless and exhausting toil of adulthood and a reflection of McCartney's relationship with Lennon.

"The song was written before John's death in December 1980, but when the album came out in April 1982, people thought it must be about him, that it was about our trying to outdo each other," McCartney wrote in "The Lyrics: 1956 to the Present. "Of course I can see how it could fit that interpretation, because John and I did try to outscore each other — that was the nature of our competitiveness — and we were both very upfront about it."

That Day Is Done

In the late 1980s, two pop-rock titans of the past got together to collaborate, generating well-received music that appeared on both musicians' albums. Paul McCartney of The Beatles got together with post-punk icon Elvis Costello, and their song "Veronica" appeared on the latter's "Spike" and became one of his few American hits to chart in the top 10 on Billboard charts. Four co-written songs earned placement on McCartney's 1989 album "Flowers in the Dirt," notably "That Day is Done" — the final song the pair worked on. Costello conceived the idea, and McCartney added much to the song, including gospel-inspired, "Let It Be"-esque flourishes, which helped bring Costello's concept to fruition. It was a song about death, saying goodbye, and the regrets one feels about things they should've said and done before a loved one dies. McCartney co-signed on the idea and softened the material. "It was from a real thing. It was about my grandmother's funeral," Costello told Mojo (via The Paul McCartney Project). "It was sort of serious. He said, 'Yes that's all good, all those images.'"

The End of the End

When Paul McCartney turned 64 — the age in question in his Beatles song "When I'm 64" — he commemorated the occasion by putting together a new album, the 2007 LP "Memory Almost Full." As he approached elder statesman — and just plain "man of advanced age status" — McCartney looked ahead to his final years and his eventual death, most specifically on the track "The End of the End."

"I'd read something somebody had written about dying and I thought, 'That's brave,'" McCartney told the Daily Mail. "It seemed courageous to deal with the subject rather than just shy away from it. So I fancied looking at it as a subject myself. According to the musician, "The End of the End" is specifically about the Irish wake tradition, which involves joyous parties in honor of the deceased, and how the he would like something like that in lieu of his funeral. "So that led into the verse, 'On the day that I die I'd like jokes to be told and stories of old to be rolled out like carpets,'" he said. "I have played it to my family and they find it very moving ..."

'(I Want to) Come Home'

The 2009 drama "Everybody's Fine" is a sad movie that tugs at viewers' heartstrings in a number of ways. Robert De Niro stars as a man in mourning after the death of his wife, the rock and social glue of the family. He heads out on a long road trip to emotionally connect for the first time with each of his adult children, hoping it's not too late. In addition to the star power of the esteemed De Niro, "Everybody's Fine" had another marketing hook in Paul McCartney, who only rarely writes songs specifically for other people's movies.

When he viewed an early cut of "Everybody's Fine," McCartney agreed to write and record a song after he was brought to tears by the plot. "The fact that he's lost his wife and has grown-up children with situations of their own and is trying to get them all around the table — I could relate to that quite easily," McCartney told CBS News, referring to the 1998 death of Linda McCartney, his wife of almost three decades and his co-parent of four children." Still, he wrote the maudlin but hopeful "(I Want to) Come Home" from the perspective of the character played by De Niro.