5 Classic Rock Songs From 1971 We'll Be Blasting On Repeat 'Til The Day We Die

A year of tumultuous changes, 1971 produced enduring rock songs that radiate the rebellion as well as the doubt that marked the era. Whether raucous rockers or melodic ballads, the year's most impactful, enduring tunes reflected the cultural milestones that touched rock fans young and old, among them 18-year-olds gaining the right to vote, Apollo 14's successful moon landing after the near-disaster of Apollo 13, and protests spurred by the war in Vietnam. Dreams for a counter-culture utopia darkened with the drug-related death of The Doors' charismatic front man Jim Morrison, and the tragic death of Duane Allman in a motorcycle crash.

The songs we've chosen to be blasted at high volume until the day we shuffle off this mortal coil illustrate the genre's penchant for reinvention and connection to it roots. It seems, as Neil Young sang, that unlike us, "Rock and roll can never die." These tunes could be seen as "classic" or even "vintage," but by reflecting the messages and attitudes that marked the year that spawned them, they also mirror our concerns today. With lyrics ranging from bold and bitter to yearning and empathetic, these timeless tunes resonate just as much now as then.

The Who - Won't Get Fooled Again

The Who's "Won't Get Fooled Again" is a rock song from 1971 that sounds even cooler today. In a video, Pete Townsend demonstrates how he conjured the sinister synthesizer-enhanced organ groove that opens the song. The riff's unbearable tension is finally shattered by Townsend's raging power chords and Keith Moon's splashy drums. Then Roger Daltrey swaggers in, drawling lyrics that are defiant yet yearning.

The epic eight-and-a-half minute anthem that ends The Who's 1971 album "Who's Next" was originally planned to close Townsend's proposed multi-media rock opera "LifeHouse," Far Out Magazine reports. When that project was scrapped, "Won't Get Fooled Again," was repurposed to climax the band's fifth studio album.

"Won't Get Fooled Again," reflects the growing disillusionment of the early 1970s. The Woodstock generation's promise of peace and harmony had soured into cynical impatience with power structures. The song posits that dissatisfaction with society was erupting into violent revolution.

The song begins with a rush of high expectations as Daltrey marvels at the changes he sees, but the tune's tenor darkens as its lyrics reveal that armed conflict hasn't altered the world at all. As Townsend's arpeggiated organ-synth returns like an encroaching cloud of poison gas, Daltrey once again cuts in with an ear-splitting preternatural scream, arguably one of rock's most iconic moments. The lyric, "Meet the new boss, Same as the old boss," saves the most devastating revelation for the song's end.

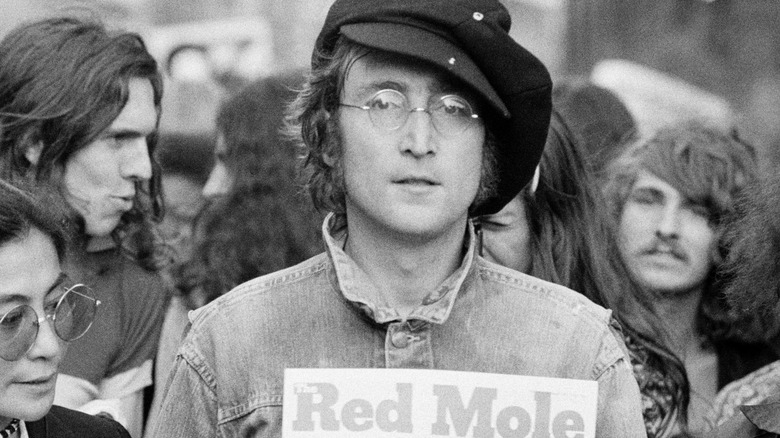

John Lennon - Imagine

An interview with John Lennon, published two days before he was shot to death on December 8, 1980, adds a poignant grace note to the tragic story of John Lennon's death. In a conversation with Playboy Magazine, archived on The Beatles Ultimate Experience, Lennon acknowledges his wife Yoko Ono's input to "Imagine," arguably the former Beatle's most beloved tune. "Yoko actually helped a lot with the lyrics, but I wasn't man enough to let her have credit for it," Lennon confesses.

The title track to Lennon's 1971 album, "Imagine" opens with plangent piano chords that repeat and build, as Lennon's plaintive, almost fragile, vocal seems to issue a straightforward plea for peace and understanding. "Imagine" can be accepted as a statement about worldwide unity, but its lyrics, particularly those about imagining no possessions or religions, have been criticized as communist propaganda. Instead, in a 1972 interview with NME, also archived on The Beatles Ultimate Experience, Lennon offered that his songwriting reflected a nuanced socialist viewpoint.

"The socialism I talk about is 'British socialism,' not where some daft Russian might do it, or the Chinese might do it." he said. The song's stated wish for worldwide harmony may seem disarmingly naive, but that could be Lennon's intent. "The first verse came to me very quickly in the form of a childlike street chant." said Lennon, quoted on the musician's official website. "It's a song for children."

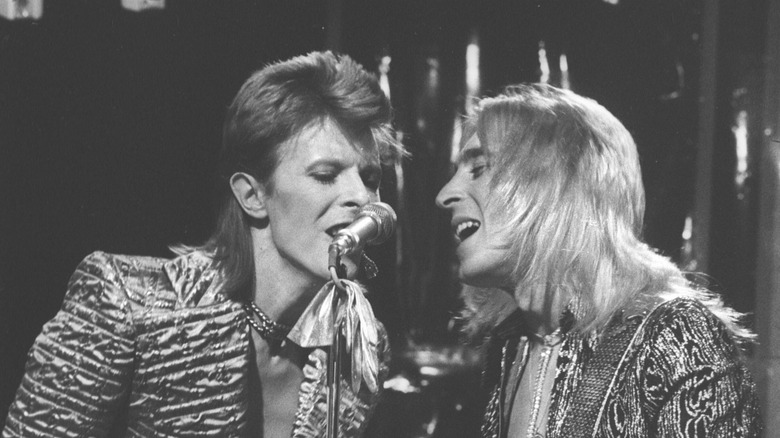

David Bowie - Changes

Throughout his career, David Bowie was often seen as unpredictable. His breakthrough single "Space Oddity" was one of the most controversial songs of 1969, banned by the BBC for depicting a failed space mission. Just three years later, Bowie delivered "Changes," a catchy, easy listening tune. It established Bowie's knack for genre-blending songwriting, while warning us to buckle up for a bumpy ride ahead.

Unlike Bowie's songs on his previous album "The Man Who Sold the World," which boasted a guitar-heavy rock sound bordering on proto-heavy metal, "Changes" featured a polished alternative pop sheen, as categorized on Allmusic. Amid percussive piano and muted saxophone, Bowie croons his autobiography, detailing wrong turns taken in his career and personal development.

The stuttered chorus that repeats the tune's title can be seen as Bowie's manifesto, announcing his soon-to-be fabled chameleon phase where he switched personas as readily as some people change socks. In 1971, a decade of successive masks lay ahead for Bowie — included Ziggy Stardust, the Philadelphia soul man of "Young Americans," and the cocaine-besotted Thin White Duke.

It's just as likely that "Changes" is simply encouraging young people working to improve their world despite being spat upon by the establishment. Bowie aligns himself with them, vowing not to be trapped in society's assigned roles, and to shun the pursuit of wealth in lieu of embracing the new and strange. It's a vow that would keep Bowie in good stead throughout the upcoming turbulent decade.

Jethro Tull - Aqualung

One of classic rock's most memorable guitar riffs opens "Aqualung," the title track of Jethro Tull's fourth studio album. Martin Barre's six-note, menacing crawl repeats before a clatter of drums spill into band leader Ian Anderson's opening line, "Sitting on a park bench." It sets a stage where we wonder what's coming next.

Anderson describes the routine of the song's seedy, impoverished protagonist Aqualung, who eyes girls lasciviously while snot drips down his nose. Soon the song shifts, both sonically and thematically, turning from fear of its principle character to empathy, as the music switches to acoustic folk with strummed guitar and plaintive piano. The tune's loud-soft dynamic and multi-part structure introduced progressive rock influences to Jethro Tull's mix of folk and blues.

The lyrics, penned by Anderson and his then-wife Jennie Franks, were inspired by a photo Franks took of a homeless man. In a 1999 interview with Guitar World, Anderson said he "had feelings of guilt about the homeless, as well as fear and insecurity with people like that who seem a little scary."

There's a decidedly Dickensian flavor to the song's storytelling, as it details the cold, miserable circumstances endured by homeless people, and shifts from distant observer to friend and ally. At the same time, the song feels distinctly modern, including details like a Salvation Army center and concerns about the dispossessed that fit seamlessly into the Industrial Revolution of Dickens' time, 1971 and today.

Marvin Gaye - What's Going On

On May 15, 1969, Renaldo "Obie" Benson, a member of the Motown vocal combo The Four Tops, witnessed anti-war protestors in Berkeley, California being attacked and shot by armed police. The incident, called Bloody Thursday, inspired Benson to develop a song. He brought the nascent tune to one of Motown's top singer-songwriters Marvin Gaye, who developed a new melody and rewrote the lyrics. The result was the chart-topping, thought-provoking "What's Going On."

Near the end of his life, Gaye experienced addiction and depression, but in the 1960s an ebullient Gaye helped shape and popularize the Motown Sound, a blend of pop, rock and soul. "What's Going On" forged a new sound as well as a game-changing songwriting approach that merged up-to-the-minute events with Gaye's personal concerns.

Kicking off with partygoers' chatter, the song segues to swaying jazz saxophone and echoing beats. Gaye's smooth storytelling vocals describe environmental destruction, picket lines, police brutality and mothers' sons sent to die in a distant land. The lyrics' plain-spoken poetry does not accuse, rather Gaye's words question various authority figures. At song's end his queries remain unanswered.

A number one R&B charts hit, Gaye's rumination on a world both in flames and coursing with compassion proved that songs conveying social messages could move multitudes. Less than four minutes long, Gaye's first-person narrative encompasses universal concerns — unease about violent unrest, empathy for others, and a wish for a better world. At timeless classic, it transcends its era.

If you or anyone you know needs help with addiction issues, help is available. Visit the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website or contact SAMHSA's National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).