Historical Films Historians Can't Stand To Watch

When it comes to historical films, you have to allow for a certain amount of creative license. For one thing, there's a huge swatch of history for which we lack any sort of reliable visual or audio record of how people actually spoke, dressed, or went about their daily lives. And real life rarely follows a convenient narrative arc neatly organized into rising action, climax, and falling action. Often, in order to turn a historical film into effective entertainment, some liberties have to be taken with the actual history.

As a result, there are few historical films you can use as research into how things actually were during their respective time periods. But most period pieces at least get most of the details right, if only to establish verisimilitude, that "truthy" feel. Some historical movies don't do a very good job at this, and some — like the films on this list — irritate actual historians to no end because they get their history so very, very wrong. And they're not comedies, where the wrongness might be part of the joke. These are serious films that want us to believe that we're getting a magical glimpse into the past — and instead have become the historical films that actual historians can't stand to watch.

JFK

The assassination of President John F. Kennedy remains a stunning tragedy in the history of the United States: a young and popular president shot to death in broad daylight, while seated next to his wife and surrounded by Secret Service agents. It also remains fertile ground for conspiracy theories involving everything from the CIA to communist spies to the Mafia. Oliver Stone's main ambition seems to have been cramming every single one into his incredibly well-made film, and the historical accuracy suffered as a result.

According to The Baltimore Sun, the director said of his 1991 film "JFK," "This isn't history, this is movie-making. I'm not setting out to make a documentary." In that sense, the movie is a towering triumph because it is as far from a documentary as it can possibly get. Yet Stone's film is so well-crafted that it often makes people think it's more accurate than it is, which happens to be not much at all.

Stone used the trial of Clay Shaw on charges brought by District Attorney of Orleans Parish, Louisiana, Jim Garrison in 1969 as the core of his script. But Garrison's case fell apart when it was revealed that his key witness had been drugged and recanted his testimony. Stone solves this by deleting the actual witness and replacing him with a fictional character played by Kevin Bacon, just one of many brazen fabrications Stone presents with the utmost seriousness.

Gladiator

"Gladiator" is a widely acclaimed movie that follows the story of the Roman general Maximus. The lead character is betrayed by the treacherous son of the emperor and forced to fight as an anonymous gladiator in order to get close enough for his revenge. It evokes the Roman Empire extremely well, even if it is a film notorious for the magical pillow that appears under Russell Crowe's head during his death scene. But as good-looking and dramatic as "Gladiator" is, a closer examination of its historical accuracy finds it to be wanting.

From the clothes worn by the German barbarians in the film's opening battle to the extreme unlikelihood that Emperor Marcus Aurelius would — or could — convey imperial power to a general as depicted, the movie gets a lot of stuff wrong. For example, in the film, the emperor doesn't like or trust his son, Commodus (Joaquin Phoenix), who then murders his father in order to seize the throne. But in reality, Aurelius named Commodus co-emperor 14 years before his death, and Commodus took power peacefully.

Most egregiously, of course, the film shows Emperor Commodus dying at the hands of Russell Crowe's Maximus. Commodus was widely disliked, and he was assassinated in his bath in A.D. 192, after ruling the empire for 12 long years. It's little wonder that many of the consultants hired to guide the historical accuracy of the film asked not to be listed in the credits.

U-571

"U-571" is a tense, entertaining war movie about an American submarine crew that poses as German sailors to board a damaged German U-boat and steal the Enigma code machine on board. The Enigma machines were used to decrypt coded messages for the Nazis, and the Allies' inability to crack those codes was a real problem in the early days of World War II. That gives the story some great stakes and real tension.

Unfortunately, it also makes the film probably one of the least historically accurate ever made. Where some historical movies are content to get a few details here and there wrong, "U-571" is so inaccurate that it was rebuked by the U.K. parliament.

The film was inspired by Operation Primrose, in which a crew of British — not American — sailors boarded a German submarine and captured the code books that were needed to use the Enigma machines. The Allies already had several working Enigmas; what they lacked were the code books. All this was accomplished in 1941, a year before the film's setting, which means the entire mission would have been meaningless. And U-571 was never captured but was actually sunk — in 1944.

The Last Samurai

In the 2003 film "The Last Samurai," Tom Cruise plays a former U.S. Army officer who's going through some serious PTSD and who takes a job helping to modernize Japan's military. He's seduced into supporting a doomed but noble samurai rebellion, training to become a samurai warrior even as the way of life they represent is about to be destroyed forever.

It's an excellent narrative, and it's largely based on the true story of Saigō Takamori. After helping to restore the power of the emperor in what is known as the Meiji Restoration, Takamori was shocked when the emperor stripped the samurai of their power and privileges, and he led a rebellion. Unfortunately, the film isn't very concerned with historical accuracy. While it's true that Japan hired Western consultants, none of them were American. The samurai were also familiar with modern weaponry and would have used firearms in their battles.

Worse, the samurai cause isn't presented realistically. In reality, it was more about class. The creation of a modern professional army elevated a class of people the samurai regarded as beneath them, and the main motive was to maintain their power and wealth. And, of course, the film shows ninjas attacking the samurai. Ninjas are decidedly cool, but Japan hadn't seen actual ninjas in centuries by that point in history.

The Patriot

Mel Gibson's 2000 film is pretty blatant about its intentions; you don't call a movie "The Patriot" if you're offering up a fair and balanced view of the American Revolution. Gibson and director Roland Emmerich consulted with the Smithsonian Institution to get the details right, and the sets and costumes are pretty spot-on as a result. And the story, about Gibson's South Carolina farmer and war veteran who reluctantly joins the rebels when his family is violently and brutally attacked, is affecting and well-done.

The filmmakers were obviously worried that they didn't have a strong villain for the story, however. The portrayal of the British army officers is outlandishly fictional — every British person in the film is a sadist and a war criminal, in that order. The film also completely gets the plight of Black Americans wrong. The decision to make it clear that Gibson's character is not an enslaver, despite living in South Carolina, is forgivable, but Black people are presented as freely fighting alongside their white neighbors in the Continental Army. While there was some discussion of raising Black units during the war, this never actually happened, and the fact is that most of the Black people in the southern colonies at the time were enslaved, something the film simply ignores.

Argo

"Argo" is based on the real-life rescue of American diplomatic workers hidden by their Canadian peers for months after the Iranian revolution in 1979, and it's easy to see why it won the Oscar for Best Film in 2013. The story of a fake sci-fi film production funded by the CIA as cover for a tense rescue operation is entertaining as heck. It's too bad that almost nothing shown in the film actually happened.

Sure, the whole fake-film operation that allowed the Americans to assume the identities of a Canadian film crew in order to escape Tehran is 100 percent true. But almost all of the details in the film are wrong. Scenes like the one in which the Americans are forced to somehow pretend they know what they're doing in a public market while suspicious Iranians watch them closely, or when the Iranian Revolutionary Guard chases their plane as it races for takeoff, simply never happened. And the character of Lester Siegel (memorably portrayed by Alan Arkin) is entirely fictional, erasing several real heroes who actually existed and risked their lives to perform the rescue.

10,000 BC

Roland Emmerich is a director known for two things: Big, splashy special-effects-driven movies and wild historical, scientific, and general inaccuracy; "10,000 BC" may be Emmerich's greatest achievement in terms of the latter.

The film's list of lavish historical errors include depicting people building the pyramids in Egypt, the use of steel (the earliest examples of which date to about 1800 B.C.), and enormous, thriving cities. Most of the trappings of civilization the film shows — monuments, writing, and farming — were either just getting off the ground or wouldn't show up for thousands of years.

That's not to say that 10,000 B.C. was the dullest period in human history; far from it, in fact. Our species was transitioning from the Paleolithic — an enormous span of time that saw the first anatomically modern humans evolve from their hominid ancestors — to the Neolithic period, when we began to adopt a more settled lifestyle. This Mesolithic period varied from location to location, but saw some of the earliest attempts at agriculture, permanent settlements, organized religion — including monuments such as Göbekli Tepe — and some seriously impressive stone tools. Building pyramids with woolly mammoths, we were not.

300

Everyone loves "300" as a movie. Gerard Butler in a loincloth shouting, "This! Is! Sparta!"? Hyper-stylized battle scenes? A King of Persia who's apparently 16 feet tall and not entirely human? The Immortals? Yes, please. But for a film explicitly based on real people and a real and extremely important historical event (the battle of Thermopylae in 480 B.C.), its entire attitude toward historical accuracy is pretty laid-back.

The legendary Spartan warriors probably didn't go into battle wearing what are essentially loincloths and body oil; they most likely wore armor like every other sensible fighting force of the time. Just about every aspect of the invading Persian army is wrong, too. In the film, the Persian Emperor, Xerxes, summons warriors from all corners of his empire to throw at the Spartans. But in reality, the warriors that are shown come from much later in history, and most were never under the control of the Persian Empire, even at its largest extent (which was pretty large).

Finally, the film's worst sin is positioning the Spartans as defenders of democracy and freedom. In reality, they were a society built on the exploitation of enslaved labor. But you wouldn't know that from the film.

Enemy at the Gates

"Enemy at the Gates" is a 2001 film starring Jude Law and Ed Harris as rival snipers — the former defending Stalingrad for the Soviet Union, and the latter being part of the invading Nazi forces — who engage in an epic showdown that turns the tide of the battle. It's a tense and gritty story set against one of the most famous battles in modern history, during which as many as 2 million soldiers died over the course of the siege. Many see the battle as a turning point in World War II, as the Nazi forces were trapped and slowly whittled down over the course of five months, until they finally surrendered because they literally had no food or ammunition left.

Paramount Pictures bought the script with the understanding that it was based on a true story, which was awkward because it turns out that the whole story may have essentially been an invention of Russian propaganda. Although Law's character, Vasily Zaitsev, was based on a real (and quite legendary) Soviet sniper, there was never a rival Nazi sniper, much less a complex game of sniper chess between the two as depicted in the film. Undeterred, the director, Jean-Jacques Annaud, continues to describe the film as based on a true story.

Darkest Hour

There's little doubt that Winston Churchill was one of the most fascinating figures of the 20th century, or that Gary Oldman's performance as the former British Prime Minister in 2018's "Darkest Hour" is incredibly good. Churchill was an incredibly capable leader and remains an incredibly important historical figure, but as good as it is, the film gets much of the story wrong.

First and foremost, Churchill is portrayed as a heavy drinking, broken old man when World War II erupts. However, although he'd been pushed out of the main corridors of power, Churchill still had a lot of influence and support in the government and the Conservative Party at the time. Worse, as The Atlantic details, the pivotal scene where Churchill rides the London Underground and is convinced by a group of regular Londoners to resist Hitler to the last breath is pure fantasy. Born into the aristocracy and well-known to spend lavishly, it is highly unlikely Churchill would have ever rubbed shoulders with common folk in the Underground.

The film also avoids many of Churchill's flaws — like his flagrant racism and classism — while giving credit for his brilliant leadership to a chance encounter with a bunch of anonymous citizens on a train. Churchill was many things, but none of them are on display in this otherwise gripping film.

Braveheart

This 1995 film starring Mel Gibson depicts the very real William Wallace and his very real First War of Scottish Independence during the 13th century. It's a stirring, exciting story, and Gibson's performance remains iconic in modern cinema — but it gets a seriously failing grade when it comes to historical accuracy. Literally. Historian Alex von Tunzelmann gave it a "Fail" in her review for The Guardian.

Von Tunzelmann's laundry list of historical errors is striking in how easily some could have been avoided. The opening voice-over declares that King Alexander III of Scotland died in 1280, when he actually died in 1286. William Wallace is depicted as growing up poor, whereas the real Wallace was wealthy. And the Battle of Stirling Bridge is set in a grassy field where there is an incredible lack of bridges. It's almost like they're not even trying. In order to engineer a love interest for Wallace (and some drama), the film also plays fast and loose with time and space. As War History Online notes, Princess Isabella, who becomes pregnant with Wallace's child after they fall in love, was in reality nine years old when Wallace died.

Perhaps the most blatant indication that the filmmakers just didn't care is the way the Scottish warriors are costumed. On the one hand, they paint their faces as if they're the ancient Celt and Pict tribes that lived in Britain during Roman times. On the other hand, they're wearing kilts, which wouldn't be invented for centuries.

Amadeus

If all your knowledge about Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart comes from the excellent, multiple-Oscar-winning 1984 film "Amadeus," you may think you know three basic facts: Mozart was a musical genius (true); Mozart loved a good fart joke (also true), and that Antonio Salieri hated Mozart, conducted a cruel gaslighting campaign to drive him insane, and probably indirectly caused his death (almost certainly not true in any way).

"Amadeus" tosses facts out the window in favor of drama. The film gets credit for accurately portraying some of Mozart's more childish and fart-loving personality traits, but the whole Salieri-hated-Mozart business was fiction, drummed up by Russian writer Alexander Pushkin after both were dead. The film explicitly makes many of Mozart's later works seem like failures when in fact they were uniformly successful, and the whole business with Salieri dressing up like his dead father to commission the Requiem actually happened in a completely different, Salieri-free way.

Peter Shaffer, who wrote the play the film was based on, was up-front about the lack of facts in this historical story, saying (via the BBC), "Obviously Amadeus on stage was never intended to be a documentary biography of the composer, and the film was even less of one."

Pearl Harbor

You might be surprised to learn that Michael Bay's "Pearl Harbor," a film directed by a man best known for blowing things up in movies about giant robots, is not regarded as a well-researched historical film. While the actual attack on Pearl Harbor is rendered fairly accurately, the film is riddled with mistakes.

Ben Affleck's character joining a British fighter squadron created for American pilots (because the U.S. hadn't yet entered the war) isn't totally crazy, but he wouldn't have been able to keep his officer's commission when he did. The film's depiction of Japanese planes bombing a hospital never happened, as the Japanese restricted their attack to military targets only. But films require villains to do terrible things, so making up this detail helped to make the Japanese seem deserving of good old American vengeance.

While big changes like that might be done knowingly in the service of a better story, the filmmakers got small details wrong, indicating a general lack of research. One obvious example is the cigarettes shown in the film. Sure, folks in the 1940s smoked like there was no surgeon general's warning on each pack (because there wasn't), but showing people smoking Marlboro Lights 30 years before they were introduced is just bad history.

Windtalkers

"Windtalkers" came out in the halcyon days of 2002, when Nicolas Cage was still a bona-fide A-List movie star and not a slightly crazy B-movie icon screaming about the bees. It is a prestige film telling a story from World War II that doesn't get a lot of attention: the Navajo Windtalkers.

They really existed, and the U.S. armed forces very much relied on Navajo code talkers during the war. The Navajo language was ideal because of its complexity, rarity, and lack of written form, which gave the Germans and Japanese nothing to work from. The code talkers then took it a step further by using a form of word association code that further obscured the true meaning of the messages.

So far, so good, but it's when we get to the actual plot of the film that everything goes wrong. In the story, the code talkers are so vital to the war effort that they cannot be allowed to be captured. Nic Cage stars as the PTSD-suffering soldier assigned to protect his "windtalker" at any cost, or to kill him if it looks like he's going to be captured. This is simply not true: The code talkers were certainly useful and contributed tremendously to the war effort, but the capture of a single code talker wouldn't have lost us the war, and no one was ordering summary executions on the front lines to keep them out of enemy hands.

Flyboys

You might not remember the 2006 film "Flyboys," starring James Franco, since it didn't exactly set the box office or awards season on fire. Depicting the early days of aerial combat in World War I, the movie should have been great fun. Instead, it's a historical nightmare — and the reason is pretty simple: The military adviser they hired to consult on the film was a fraud.

For a start, none of the airplanes shown in the film are historically accurate. The Germans are shown flying Fokker D1s, which were used in World War I but weren't as common as the film makes it seem. The Americans are shown flying Nieuport 17s, but those planes had actually been decommissioned before the Fokker was in the air. According to producers, this was an aesthetic choice because the planes were visually dissimilar, making it easy for audiences to tell the two sides apart in dogfights.

But the real answer might be simple incompetence. The man hired to be the military adviser on the film, John Livesey, was a fraud who invented a military career and eventually wound up in jail. Livesey claimed to have served in the Parachute Regiment (with a medal for gallantry) and to have fought in the Falklands war and Northern Ireland. In reality, the expert that the producers were paying to ensure that their film got the details right had served just a few years in the Catering Corps.

Alexander

Oliver Stone's whole aesthetic could be described as "reality-adjacent," so literally no one expected his 2004 epic historical drama "Alexander" to be an educational film about the man who once conquered most of the known world. But the movie is so disdainful of historical fact that it's basically a work of fiction.

Stone completely distorts just about every detail of Alexander the Great's life. The historical figures are depicted as younger than they actually were, and Stone deletes important battles from the story, combines others for no reason aside from convenience, and misrepresents how formidable Alexander's enemies were, especially the Persians. That means the film actually fails in one of its main reasons for existence: exploring the military genius of Alexander.

One of the biggest problems with the film is its depiction of Alexander's sexuality. Alexander marched with his armies in the fourth century B.C., so modern-day perceptions of sexual orientation — or at least those of a few decades ago — simply didn't apply, and yet the film insists on treating his possible bisexuality as a major scandal when it almost certainly wouldn't have been. And we actually don't even have enough evidence to determine Alexander's sexuality one way or another.

Pocahontas

Just because your film is an animated feature aimed at kids doesn't let you off the hook for historical accuracy. Disney's "Pocahontas" is a delightful movie, but one that fails big-time when it comes to getting its facts straight. Kids may assume that the movie is pretty accurate, which means it's teaching those kids a version of history that's totally wrong.

The worst (and creepiest) thing the film gets wrong is Pocahontas' age. In reality, she was about 10 years old when she met 27-year-old Captain John Smith. The film makes her into an adult and spins a totally fictional tale of a romance between them, which would have been really horrifying if true. The film builds to the big moment when Smith returns home to England and Pocahontas decides to stay behind with her family, but in reality, Pocahontas did marry an Englishman many years later and sailed to England with him.

The film also distorts history by toning down the colonial violence inflicted on the Native Americans by the British. The film strongly implies that the Native Americans were just as violent and intent on fighting as the British, and then depicts everyone coming together to strike a new peace accord. In reality, the British brought along several nasty diseases that killed off up to 90 percent of the Indigenous population, and the European colonizers violently seized land from the survivors.

Shakespeare in Love

It's true that we know next to nothing about Shakespeare's life. Indeed, there are entire periods of his life that are a complete blank. That makes it easy to just make stuff up, of course, but it's almost certain that almost nothing shown in "Shakespeare in Love" is true.

The film suggests that "Romeo and Juliet" and several other works by the Bard were inspired by an actress that Shakespeare loved, who breaks tradition (and the law) by dressing as a man to pursue her love of acting. In reality, Shakespeare's plays liberally borrowed from previous stories and reworked old plots, a pretty common practice back in those days. Furthermore, the film is explicitly set in 1593, and many of the works he supposedly writes in the story weren't composed until nearly a decade later.

There's also a subtle but striking inaccuracy in that the film has exactly zero characters of color. This might seem to make sense if you're not familiar with history, but there was actually a sizable Black population in London at the time. While it might be accurate that there are no people of color as main characters, not having any in the background at all is a complete history fail.

Black Hawk Down

"Black Hawk Down" is a thrilling war movie that depicts the Battle of Mogadishu in 1993, following a group of U.S. Special Forces soldiers who have to fight their way through the streets against the forces of a vicious Somali warlord. It's based on a real event, and the film does a reasonably good job of depicting the desperation of urban warfare. Unfortunately, the film gets a lot of really important aspects of the events absolutely wrong.

For one, it ignores the high number of civilians killed in the action, making it seem like everyone who dies was a voluntary combatant. It also completely ignores the presence of child soldiers, preferring not to deal with the complex moral questions attached to fighting 10-year-olds.

Perhaps most egregious is the way the film portrays the American forces not only as mostly white but also as acting alone when, in fact, they were supported by a large number of Pakistani and Malaysian soldiers. Those soldiers were our allies and were heavily involved in the battle, but they are completely deleted from the story — the only Pakistanis we see are fawning servants waiting for the soldiers back at their base. Pakistan's then-President Pervez Musharraf was so irritated about this that he denounced the movie.

The Alamo

John Wayne was one of the biggest stars of all time. He also wasn't above putting his personal politics into his films, and he made "The Alamo" as a vehicle for a certain view of American patriotism that wasn't exactly historically accurate. While the broad strokes of the Battle of the Alamo — which saw about 200 Texans fight a professional Mexican army of thousands — are true enough, Wayne made several changes that go against history.

First and foremost, it makes it look like the Texans were fighting for the American way when, in fact, they were fighting for their own claim to the land: Texas hadn't even declared independence when the battle broke out and was years away from becoming a state. Wayne wanted to show heroic Americans defending their liberty when it was actually desperate Texans fighting to keep ownership of their land.

The film's inaccuracies also extend to specific historical figures, many of whom are depicted in wildly incorrect ways. One example is James Bowie, who, in reality, was too ill to fight in the battle. The film shows him valiantly battling the Mexicans despite this inconvenient fact. Davy Crockett is shown dying a spectacular, heroic death involving a mortal wound and a big explosion, and while it's fairly certain he did die in that battle, the few eyewitness accounts range from being killed surrounded by slain enemies to being captured and executed by the Mexicans, with no explosions by any account.

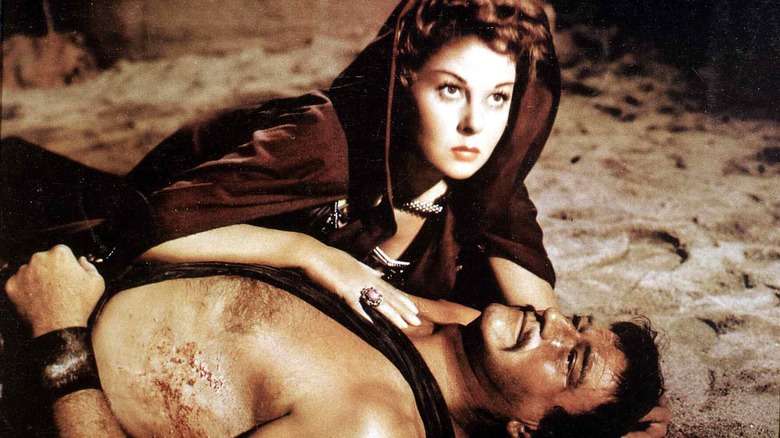

The Conqueror

Even in 1956, it was an interesting choice to make a movie about Genghis Khan with a mostly-white cast, but that's exactly what "The Conqueror" is. John Wayne played the titular conqueror, delivering the lines of a medieval Mongol warlord with the same cadence he delivered every other line in every other movie he was in. Supporting him were the admittedly lovely but still also white Susan Hayward as his wife Bortai and accomplished (white) actress Agnes Moorehead as his mother Hunlun, a few years before her classic sitcom role as Endora in "Bewitched." As a small blessing, only John Wayne is styled to look East Asian; Moorehead's exoticism is largely portrayed through funny little hats, and Susan Hayward was allowed to look like Susan Hayward.

In addition to the hard-yikes of the casting and John Wayne's eyebrows and mustache, "The Conqueror" is also infamous for possibly having killed many of its cast and crew. The Great Basin of the United States stood in for the vast steppes of Central Asia, and the primary location of St. George, Utah, was close to and downwind from a nuclear weapons testing site. Ninety-one out of 220 cast and crew developed cancer, including Wayne, Hayward, Moorehead, director Dick Powell, and, indirectly, actor Pedro Armendáriz Sr., who died by suicide after a cancer diagnosis. The high rates — and relatively young ages at diagnosis — among the cast and crew were matched by many cancers among St. George residents, and while carcinogenic activities such as smoking and drinking were more prevalent then, Moorehead didn't do either.

Elizabeth

Inmany ways, "Elizabeth" encapsulates what people love about historical films. Dramatic situations, beautiful but unwieldy dresses, poison, and people making grand statements in beautiful interiors. Unfortunately, many of these situations are dressed up for the film, and even some of the poison is fake.

"Elizabeth" shows the dangerous period immediately surrounding the young queen's accession to the throne, with political and religious machinations endangering her at every turn. One of her most powerful rivals is the grand and terrifying Marie de Guise, the French queen of Scotland who governed it in the name of her not-yet-grown daughter, the luckless Mary, Queen of Scots. The movie has her being poisoned by Elizabeth's adviser Walsingham, but in the real world, she simply died of illness.

Many of the other issues in the film are due to compression of time or simple dramatic license. For example, William Cecil served Elizabeth faithfully for decades; she didn't shoo him out the door once she got her throne under her. The film's flamboyant, cross-dressing Duke of Anjou was a possible husband for Elizabeth when she was pretending to be considering marriage, but this courtship occurred much later; it was his brother, Henri III, who many historians believe was gay. Elizabeth's famous white-faced aesthetic is brought forward in time as well: her complexion-wrecking bout of smallpox didn't strike her until she'd been queen for several years.

Elizabeth: The Golden Age

The sequel to "Elizabeth," "Elizabeth: The Golden Age," returned with more dresses, more intrigue, and more inaccuracies. Like many historical dramas, it compresses time to make its narrative more coherent and more suitable for a contained film, but it also simply makes some stuff up.

Many of the inaccuracies center on the person and political schemings of Elizabeth's cousin and rival, Mary, Queen of Scots. While Mary did spend the last period of her life in Elizabeth's custody in England — as a potential heir to the English throne, Mary was too dangerous to be allowed to wander around freely — the character's situation in the film doesn't match that of her historical inspiration. Mary grew up in France and therefore spoke with a French accent: actress Samantha Morton's lovely Scottish diction is charming but highly improbable. The real Mary would have been under tighter guard than depicted in the film, which also sanitizes her execution: the executioner needed more than one strike and didn't account for her wig afterward, which caused him to drop her severed head on the floor.

The great battle against the Spanish Armada is also altered from the historical record. While it was an English victory, the English fleet was both much stronger than the film shows and aided by a storm that scattered the Spanish fleet, known affectionately as the "Protestant Wind." And the little Spanish princess that the film's King Philip II was plotting to put on England's throne once he disposed of Elizabeth? She was an adult woman in 1588 — the year of the Armada — with a future in the Low Countries already planned out for her.

Becket

Based on a play by Jean Anouilh, 1964's "Becket" centers on the tension between England's King Henry II and the Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Becket. Unfortunately, by focusing so tightly on those two figures, the movie does a disservice to the two most important women in Henry's life. Portrayed as embroidering grumps in anachronistic headgear, Henry's mother, Empress Matilda, and wife Eleanor of Aquitaine were two of the most fascinating and powerful women of the High Middle Ages, but you wouldn't know it from "Becket."

Henry would never have become king if not for his mother. The heir to her father, King Henry I, Matilda was the widow of the Holy Roman Emperor when she began a civil war against her cousin to claim her inheritance in England and Normandy. Personally courageous and a competent strategist, she almost won the war. However, her "crisp" personality alienated the population of London and at one point she released her rival, Stephen, after capturing him. When Stephen's heir died, an agreement between the two sides allowed her son Henry to be tapped to be the next king.

Eleanor of Aquitaine was the fabulously wealthy, famously beautiful queen of France when she divorced her husband to marry Henry II of England. She had already been on crusade in the Holy Land, and she brought the English crown the duchy of Aquitaine, a huge chunk of southwestern France. Over the course of her turbulent marriage she rebelled against Henry in alliance with their sons, spent years in captivity, and ultimately outlived Henry to help her sons govern their sprawling domains.

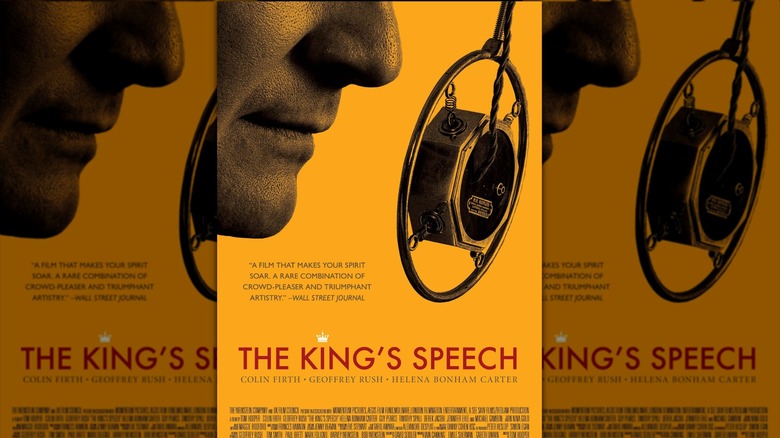

The King's Speech

Most people don't like talking about Nazis, but if you're making a movie about the leadup to World War II, you have to. "The King's Speech" takes a few liberties with timelines in the interest of making a demanding process of speech therapy compelling, which is fair, but it also sanitizes the unsavory Nazi sympathies of the movie's indirect villian, the selfish and fascist King Edward VIII.

Edward VIII is usually remembered for abdicating the thrones of the United Kingdom and the other Commonwealth realms (Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, and so on down the line) in order to marry Wallis Simpson, a divorced American from Baltimore whom few people except Edward thought should be queen of anything bigger than a crab cake festival back in Maryland. What history sometimes forgets and the movie largely ignores is that Edward (and Wallis) were effectively Nazis. They were friendly enough with the fascist powers-that-were to ask them to have the German occupation troops look after their house in France after the invasion.

The British government made Edward governor of the Bahamas during the war, which sounds like a treat if you don't factor in the fact that they wanted him far away from Europe, just in case he felt like trying to ride a German invasion of England back to the throne. His sour legacy does not deserve the kid-glove treatment "The King's Speech" provides.

Phantom of the Opera (2004)

The opening sequence of the 2004 film treatment of "The Phantom of the Opera" is one of the best in a movie musical. A ruined old theater is suddenly revived, with dust flying away, colors regaining their vibrancy, and fallen chandeliers springing back to the ceiling and lighting themselves as the famous theme from the show begins. And then they ruin it all with the caption "Paris 1870."

France was in the middle of losing the Franco-Prussian War for much of 1870, and that year was one of the very few in recent-ish history during which being in Paris would have been profoundly unpleasant. The ill-fated Emperor Napoleon III was captured at the Battle of Sedan on September 1, and by September 19 Paris was under siege. The siege lasted until January, and conditions within the city became so grave that horses, rats, dogs, cats, and the animals in the zoo were consumed: A famous restaurant Christmas menu offered camel, kangaroo, and a variety of wines (it was, after all, still Paris).

The following year saw little improvement. After the siege ended and the Germans went home, the Parisians were so furious that they rebelled against the central government, and France had to invade its own capital.

Firebrand

Katherine Parr, in life and in death, deserves more than she's gotten. Henry VIII's last wife was, with her divorced predecessor Anne of Cleves, one of the two out of the famous six wives to survive the king. Clever and devout, Katherine was among the first women to publish a book in English under her own name, a massive achievement even if "Lamentations of a Sinner" doesn't sound like a rip-roaring read for modern audiences. A kind stepmother, devoted religious reformer, and astute political player within the limits available to her, she also had a happy ending, marrying for love after Henry's death. Sadly, she died in childbirth not long after. But despite all this, "Firebrand" doesn't really tell Katherine's story. Instead, the film fabricates a relationship between her and female preacher Anne Askew.

Askew was herself deeply cool, sassing her torturers in the Tower of London before her execution for heresy, but there's no evidence she and Katherine knew one another well or even at all. Katherine is also imprisoned for heresy in the film; in real life, she was investigated but never arrested. She was never pregnant by the king — news that would have been trumpeted at the heir-hungry court — and she almost definitely did not murder Henry VIII.

The Madness of King George

A reigning monarch rendered incapable of rule by mental illness is a fascinating film topic, as well as a good warning about giving too much authority to a single person. "The Madness of King George" can be forgiven for massaging the political ramifications of its subject's illness; there probably are people who would like to watch a movie about Parliament, but probably not enough to fill theaters. Its treatment of the titular disease, however, has some more explaining to do.

The film takes for granted the popular but unproven theory that George's illness came from a genetic disease called porphyria, which covers a range of related disorders caused by faulty synthesis of a crucial oxygen-carrying molecule in the blood. Porphyria can cause psychiatric symptoms — as well as the discolored urine portrayed in the film — but it is much more of a physical disease, which is at odds with the film's focus on the behavioral treatment that the king receives. Further analysis of historical evidence, such as George's letters, has led some historians and medical experts to believe that bipolar disorder was more likely than porphyria.

Finally, the film doesn't address the most tragic part of George III's illness. It focuses on his first serious spell of mental illness from 1788-89, from which he recovered, neglecting to mention the depressing but relevant fact of his second episode. In 1811, George again fell seriously ill and was incapable of governing until his death in 1820.

Passion of the Christ

Whatever else you might argue about the film or its social context, "The Passion of the Christ" is not meant to be a note-perfect representation of Roman Judea. It's a religious and spiritual work meant to inspire the faithful and intrigue the rest, but even so, the movie's details varied enough from known facts about the historical setting to annoy (and amuse) some observers.

The film correctly shows Aramaic as the language spoken by everyday people, but it was probably Greek, not Latin, that was spoken in the government: few of the people the Roman state had to govern in this area grew up speaking Latin, but educated people often knew Greek. Indeed, Jesus would not have known the Latin he uses in the film, and might not even have had Greek. The Jewish population Jesus belongs to is shown as a monolithic group, unified in its views and with its own security force, but these are both laughable. Judean society was highly divided during the time in question, and the restive local population would never have been allowed to arm itself and potentially form a seed of resistance to Roman rule.

Finally, the film made one notable change in the name of dignity. Victims of crucifixion usually suffered nude, but the film, conscious of both the ratings board and the complex emotions audiences might have in seeing a major religious figure quite literally as God made him, erred on the side of modesty.

The Duchess

Putting Keira Knightley in elaborate period costumes and letting her enjoy herself is a recipe for a fun movie, but you won't necessarily get an accurate one. "The Duchess," in which Knightley stars as the glamorous and influential Duchess of Devonshire, shears away some of the complexities of the actual duchess and leaves the film without some of its main character's most interesting traits.

The real-world Duchess of Devonshire, Georgina Cavendish, was an interesting and complicated woman who was one of the foremost trendsetters of her day, with a wide range of interests that included government, mineralogy, and fashion. Friendly, social, and what passed for progressive among the British upper classes at the time, she involved herself in politics, campaigning for the reform-minded Whig party in parliamentary elections. She was also a compulsive gambler and emotionally intense to the point of writing letters in her own blood (one hopes they were brief).

"The Duchess" smooths out the duchess. Her gambling, drinking, and compulsive spending are limited in the film, as is her role as a fashion influencer: she wears some great costumes, but they're not clearly connected to her own instinct to set trends. The duchess's political activities are also soft-pedaled, portrayed as something of a phase instead of one of the great interests and projects of her life. Georgina Cavendish was friends with Marie Antoinette and a published author, too, but a movie featuring the fullness of her life, sadly, is yet to be made.

The Imitation Game

Most of the inaccuracies in historical films, however severe, fall short of being genuinely offensive. This isn't so for "The Imitation Game," a biopic about the life of codebreaker and mathematician Alan Turing that accuses its central figure of wartime treachery.

The real Alan Turing worked on wartime codebreaking during World War II, making such Allied successes as the Normandy invasion possible. He also created the famous Turing test; a computer or language model passes the Turing test if a user thinks they are communicating with a human being, rather than a computer. Turing was also gay, and an ungrateful British government prosecuted him for it. Forced to take female hormones to kill his sex drive, Turing died by suicide in 1952.

A key point here is that queer people were not, in Turing's day, allowed to work in sensitive government departments because they were felt to be untrustworthy. The film takes this untrustworthiness as a given, with a Soviet spy in Turing's codebreaking unit blackmailing him over his homosexuality: The spy is based on a real person, but he did not work closely with Turing in real life. Instead of focusing on the extraordinary legacy of Turing, "The Imitation Game" heavily implies a homophobic trope; that a gay person would apparently betray their country to conceal it.

If you or someone you know is struggling or in crisis, help is available. Call or text 988 or chat 988lifeline.org

Cleopatra

The 1963 historical epic "Cleopatra" was made largely as an excuse to dress Elizabeth Taylor up as an Egyptian queen, with so much eyeshadow and such heavily ornamented hair she deserved an Oscar for remaining upright. Nevertheless, for a mid-20th-century film at least, it's relatively faithful to the known history (aside from Egypt being full of white people) with the notable exception of how it portrays the pivotal naval battle of Actium.

Actium was the last big battle of the war between Octavian, who would shortly be rebranded as Augustus Caesar, and his rival Marc Antony, backed by Cleopatra's Egypt. Marc Antony and Cleopatra lost the battle, Egypt, and their lives in fairly short order. The battle of Actium is one of the major set pieces of "Cleopatra," portrayed at great cost and with little realism. For example: if a battleship is about to ram the side of your boat, chucking a javelin at it won't really do much. Warships of the time had their main rams underwater, so that the holes they made would be underwater and cause the rammed ship to sink, which is not clear in the film; all it shows are fancy pointed sticks attached to various boats. And fighting with your sword on a boarded ship without having brought your shield? Unheard of.