Insane Times Music Artists Were Screwed Over By Their Recording Companies

Being a rock star must be great, right? You've got loads of fans, all the luxuries you could hope to enjoy, and even tours? They're not so bad, right? At least you've got some ultra-comfy rides and some of the best hotel rooms around. That's not even getting into the fact that you're getting paid to do what you love, and there's a lot to be said for that.

Only... all too often, that's not the case at all. Some of the biggest and best names of the rock world have gotten caught in some of the worst contracts you can possibly imagine, and some of them are even worse than you might think. The result isn't just one less Lamborghini than they would have been able to afford otherwise, it's bankruptcy, debt, and lawsuits where musicians are forced to fight for what they deserve.

Record companies are out to make money, and at the end of the day, there's a lot of shadiness going on that proves they don't care how they do it, they're perfectly happy to get rich off the backs of the people with the real talent. Creating art is hard, and some of these names have paid dearly for their art.

Not-so-fortunate son

If John Fogerty seems a little bitter lately, that's for a good reason. Let's put it this way: when Saul Zaentz, the owner of his long-time label Fantasy Records, died in 2014 from Alzheimer's-related complications, there were no condolences. Instead, Ultimate Classic Rock notes that Fogerty simply tweeted a link to a video of his song "Vanz Can't Dance" (originally titled "Zanz Can't Dance")... featuring some animated pigs.

He's been pretty open about the difficulties he's had with Fantasy Records, The Guardian says, and things kicked off when Creedence Clearwater Revival split. Fogerty suddenly found everyone in the band was released from their contract... except for him (via The Sound). And while part of the deal was that Fantasy was supposed to give him royalties for the CCR songs he'd written, well, in his own words: "[...] I've had to fight to get royalties from 1980 and every year after that. Basically, to get paid I had to sue them, that was their stance."

And there's been a lot of lawsuits. Fantasy — and Saul Zaentz — continued to dog him even after he'd signed a solo contract with Warner Bros. They sued him, claiming his new work was basically his old work with new lyrics. In other words, they sued him for plagiarizing himself. According to Rolling Stone, he won the suit by playing both songs in court and proving they weren't the same... but the lawsuits just kept flying back and forth.

Going rogue to prove a point

Brad Paisley has had a lot of trouble with his record label, and according to Business Insider, it goes way back to 2002. That's when he first sued them: he wanted the numbers on what he should have been getting for royalty payments, but there was a problem. The judge denied him, at least for a while. Why? Because built into his contract was a footnote, stating that he absolutely couldn't inquire about or challenge royalty payments until after 2006.

Shady? He thought so, and after suing again in 2011, he sued them yet again in 2014, claiming they owed him a whopping $10 million. Sony, says Billboard, responded, saying they'd handed over around 40,000 pages' worth of documents, but that his team was "unresponsive and unpunctual in its responses."

Unfortunately for Sony, the 2014 lawsuit coincided with the release of Paisley's Moonshine in the Trunk album, an event that he saw as the perfect opportunity to stick it to the man. He started leaking clips of the songs on social media, and even enlisted the help of high-profile friends to do the same. He did say (via USA Today) that some over at the label thought it was pretty funny, and while he says he probably messed up some promotional plans they had, he added, "I like the damage-control aspect of it."

Nuthin' but a hound dog

It's one of the most famous openings in rock history, and the song is the simply-named "Hound Dog." Almost everyone knows the version that Workers World describes as Elvis' "signature song," but the one who sang it first was Big Mama Thornton, four years before Elvis. Songwriters Mike Stoller and Jerry Lieber have confirmed (via the Library of Congress) that yes, they wrote "Hound Dog" specifically for Thornton after seeing her perform. They took their song to drummer, singer, and producer Johnny Otis, who cleaned it up, gave it to Thornton, and recorded the song that led to her recording contract with Peacock Records.

But the song's popularity led to an almost immediate feeding frenzy, including a quick rewrite to change the lyrics to be sung from a male perspective. That was one of the first lawsuits, says American Blues Scene: Peacock Records immediately sued Sun Records, and Sun had to pay up. Following lawsuits would lead to "Hound Dog" becoming one of the most litigated songs ever... but what about Thornton, who had the massive voice and talent that would give Elvis the song that catapulted him to a career worth more than $4.3 billion?

Those in charge of her career didn't take nearly as good care of her: she earned only $500 from the song, and when she died in 1984, it was in poverty.

Why tour when it just puts you into debt?

TLC helped kick off the 90s with some massive successes. But behind the scenes, things were not well. The Los Angeles Times confirmed that in 1996, when Lisa "Left Eye" Lopes talked to them about how — at the same time they had the nation's second-biggest album, and picked up a few Grammys — they were filing for bankruptcy. She explained, "It's hard to believe that a group can sell 14 million records and still be treated so badly. But guess what? This is a cutthroat business full of greedy individuals who take advantage of young artists."

While Arista Records and LaFace Records said that they had gotten a pretty standard agreement, their terms were nothing less than shocking. Their 1991 contract netted them 7 percent on the sale of each album... after the record company deducted the price of things like promotional costs. Then, the group didn't get paid until the studios got reimbursed for studio time and a slew of other expenses: by the time that was done, they got about 20 cents per album to split three ways.

When TLC performed at the Grammys, that performance pushed them even deeper into the hole: their record company deducted the cost of paying dancers and the crew from their future earnings, amounting to tens of thousands of dollars they'd need to "earn" before they saw a penny.

How young is too young?

In 2004, JoJo became the youngest person to hit No. 1 on the Billboard charts with her song "Leave (Get Out)." She'd been signed the year before when she was just 12-years-old, and the barely-teenaged singer was locked into an impressive seven-album deal. But she quickly found out that it wasn't nearly the deal she thought it was.

According to Vulture, her next album was released in 2006, and the third simply never came. Blackground Records, she says, simply kept not releasing it... for years. And years. Her career came to a screeching halt, because at the same time they just kept failing to release her next record, they were also refusing to let her out of her contract and free her up to go elsewhere.

Things started to go sideways when the rep who signed her seemed to drop off the face of the earth, and the warnings began. It was only in 2013 that she sued on the grounds that since she was a minor when she signed, the contract legally would have ended after seven years: ie., in 2011, says Billboard. She finally won her battle to be free of Blackground in 2014.

Even pioneering icons aren't exempt from bad deals

When it comes to those early songs that shaped rock n' roll, "Tutti Frutti" is definitely on anyone's list. It's difficult to imagine what it must have been like, hearing that for the very first time... but if you think Little Richard cashed in on it, you'd be wrong. According to Forbes, he was offered a horrible deal by Specialty Records and owner Art Rupe. Rupe bought the song, rights and all, giving Little Richard just $50 and half a cent for each record that was sold.

Half a cent. Just let that sink in. By the time "Tutti Frutti" hit the half-million mark, Little Richard had earned just around $25,000... small beans, for a song that would change music history. Does it get worse? Of course it does. Every time "Tutti Frutti" was covered by a white artist, Little Richard got a big old nothing in royalties. The reason as to why someone would sign such a horrible deal was easy: "If you wanted to record, you signed on their terms or you didn't record," he said in his autobiography.

Rupe went on to defend the deal, saying that he'd been taking a chance on an unknown, so of course, it was fine. Little Richard, however, sued in 1984 for a whopping $112 million, and they settled out of court for an amount that's not been revealed.

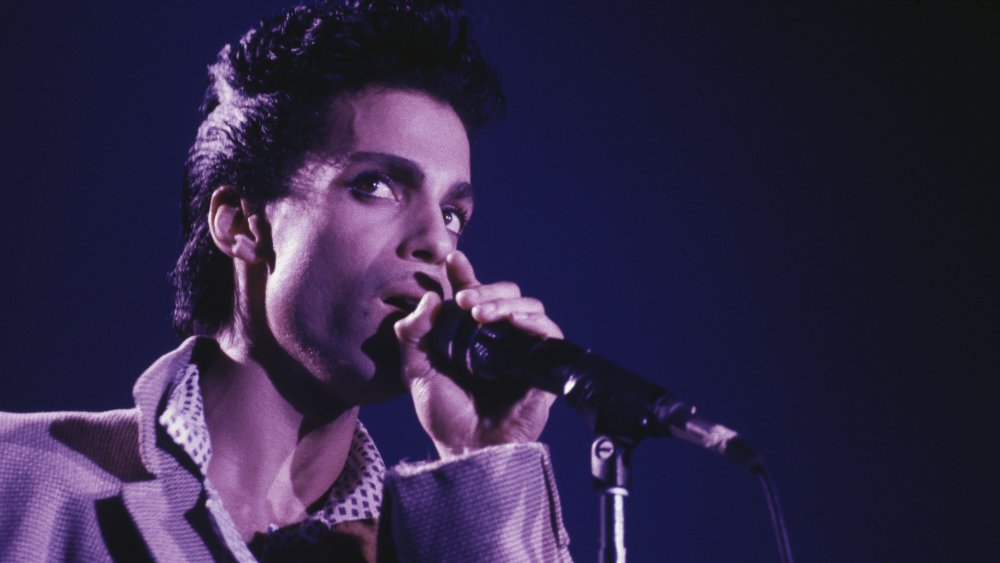

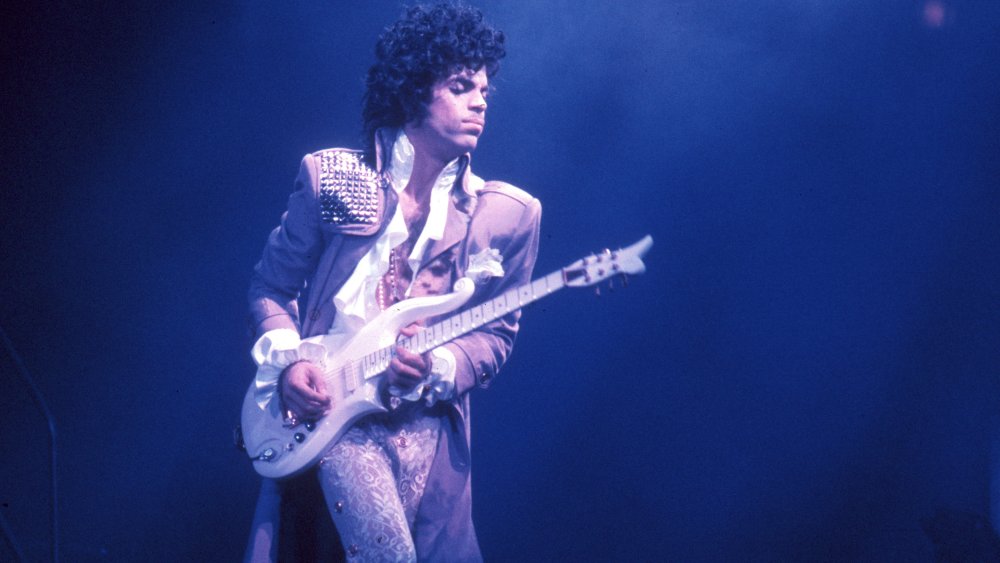

The artist formerly known as...

Prince's battle with his record company, Warner Bros., is long enough that it could fill a book or five. His determination to stand up for the rights to his own creativity was industry-changing, and while we don't have room to write a book, let's talk about one small bit of the saga: why it happened.

Prince signed with Warner Bros. in 1979, when he was just 19-years-old. His first album was groundbreaking — his name was the only credit on it, and he did all the vocals and played every instrument. (For a comparison, a Michael Jackson album released the same year had 40 musicians and 15 composers.) Prince was the real deal, and he was super protective of the music he released. He continued to put out groundbreaking stuff, says Quartz, and in the early 90s, he signed a $100 million contract for six more albums. At the same time, Warner Bros. also got ownership of Prince's entire back catalog, which was a great deal for them, not-so-good for Prince.

And that's what led to him changing his name to a symbol, writing "Slave" on his face during performances, and the horrible-on-purpose Chaos and Disorder album. And finally — in 2014 — he won, re-signing with Warner Bros., and getting control back over his own music.

The race records of the 1920s-1940s

Between the 1920s and the 1940s — the golden age of Jim Crow — a particular kind of record was hitting the shelves. They were called "race records," and the deal was that they were by black musicians, and marketed to black audiences. It was a great deal for the record companies, because, well, racism. According to History, thousands of recording artists were approached by record companies who asked them to perform so they could be recorded. They were often given nothing in compensation — pay, or recognition — but record companies cashed in.

Take Big Bill Broonzy. He recorded hundreds of songs, and in a 1947 interview, he had this to say: "I didn't get no royalties, because I didn't know nothing about trying to demand for no money, see?"

And it gets worse, says The Conversation. Not only were there no contracts offered and no royalties paid, but part of the deal was also anonymity; that means that the names and stories of countless black musicians from the early 20th century have just been lost. Some of the most groundbreaking music in blues and jazz comes from artists we simply don't know anything about today, because they were seen as a way for largely white-owned record companies to make a fortune. It's as Broonzy once put it: "Until I started running in this music business, I had never lived around no people that would kill they own brother, like, for a lousy dollar."

The black artists of the Golden Oldies

Modern music genres, notes the Observer, was built on a foundation of black culture. But here's the thing: countless musicians that shaped the industry were never compensated or credited for that, even into the 50s and the birth of rock n' roll. In the early 50s, there was something of a revolving door of groups that would hit the charts then disappear. Why? Because, historian Norman Kelley says, "[...] they were routinely swindled out of their publishing rights and underpaid for record sales."

And that's just part of the story, says the Belleville News-Democrat. At the time, the industry had a serious racket going, and it ultimately led to the promotion and success of white artists over the black musicians who originally wrote, sang, and played the songs.

What would happen is that a recording company would offer a black musician a flat fee for a song. Once they accepted, ownership of the song would go to the record companies, who would then license it to white artists. Those white artists would pay the record companies fees for permission to use the songs, and the black artists... just kidding, they're already out of the picture, and got nothing further from their music. Take "In the Still of the Night." That sold around 13 million copies and would have been worth $100,000 in royalties. Instead, writer and performer Fred Parris (pictured, right) got just $783.

Pretty much everyone vs. Universal Music Group

In 2019, a group of musicians — led by Steve Earle, Soundgarden, Hole, and the estates of Tom Petty and Tupac Shakur — filed a massive lawsuit against Universal Music Group. They were seeking more than $100 million in damages, and even if they win, well, it's not going to replace what was lost.

According to NPR, the suit accused UMG of a breach of contract. Part of their agreement was that they were going to properly and safely archive irreplaceable materials, like original recordings. Instead, master recordings were put "in an inadequate, substandard storage warehouse located on the backlot of Universal Studios [Hollywood] that was a known firetrap."

They also accused Universal of covering up the true damage done in a 2008 fire that swept through the building. While they had, at first, claimed "we only lost a small number of tapes and other material by obscure artists from the 1940s and 1950s," it start to come out that what was actually lost was somewhere upwards of 500,000 recordings from a huge number of artists, including Louis Armstrong, Lynyrd Skynyrd, Iggy Pop, Blink-182, and Rob Zombie... along with countless others. According to Rolling Stone, UMG had moved to dismiss the case — saying that the recordings were theirs, and they alone were entitled to the insurance settlement — but a judge ordered full disclosure regarding what was actually lost.

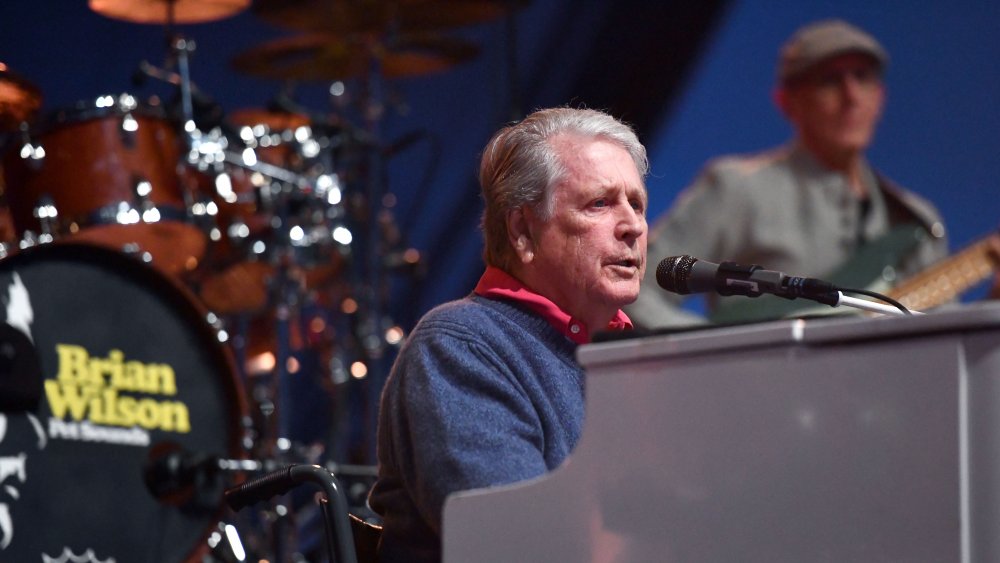

What's the opposite of good vibrations?

Being a Beach Boy was apparently tough: not only were there all the lawsuits that flew between members, but there were the lawsuits they leveled at their record companies, too. While there's not enough paper in the world for a book about their lawsuits, let's go back to one in particular: one of the first, against Capitol Records.

According to Ultimate Classic Rock, the popularity the Beach Boys had been enjoying for a good long time was starting to fade by the end of the 60s... and Capitol Records seemed to know it. In 1967 the group sued: they were unhappy with the treatment they were getting, wanted to get out of their contract, and they also wanted the $225,000 they were owed in unpaid royalties.

The solution to all that was a settlement, where it was decided the Beach Boys would be given their own label, Brother Records, which would still be distributed by Capitol. That Brother label was hardly used, though, and they weren't going to sit around and wait for things to get better. In 1969, they sued again: this time, they were looking for $600,000 in unpaid royalties, and another $1.5 million due to Brian Wilson alone. They settled, and their contract was not renewed.

It takes one person to stand up first

Look back through music history, and you'll find a lot of important precedents. That includes the one set by the first man to sue his record label and win. His name was Erroll Garner, and while it's possible you may never have heard of him, he was huge in the late 50s. He was a jazz pianist, and he hit it big in 1955 — by 1958, he'd sold a million records. His deal with Columbia came in 1956, and he was such a big star that Variety said his manager was able to negotiate for a then-unheard of deal. Any release of his back catalog, his contract said, had to be approved by him.

That, of course, didn't happen. In 1960, Columbia started to release records without his approval, and he immediately reached out with a notice to stop. When Columbia ignored it, he sued them — and they sued him right back. What followed was three years of litigation, during which Garner had to step out of the recording studio, while Columbia released two more of his unauthorized albums.

Eventually, the case went all the way to the Supreme Court, and Garner won. He received all his master recordings, a cash settlement, and Columbia promised to recall all the records they'd sold. While it's unclear whether or not they held up their end of the bargain, Garner still set a precedent in the courts: artists have rights, too.