Musicians Who Turned Down Playing At Woodstock

Over the weekend beginning on August 15, 1969, approximately 400,000 people, mostly hippies, young people, and members of the progressive "counterculture" youth movement, descended upon Max Yasgur's farm near Bethel, New York, to witness the Woodstock Music and Art Fair, billed as "an aquarian exposition" and "three days of peace and music." Sure, there were plenty of '60s-style shenanigans, but the nearly half a million attendees were there for the music. Woodstock became a defining moment of the Baby Boomer generation, as no festival had ever reached its size or scope before (and even with Coachella, Lollapalooza, and Bumbershoot since). And that was because of the musicians, who turned in historic performances. Among the bands on the bill: The Who, Santana, The Band, the Grateful Dead, Jimi Hendrix, Santana, and Crosby, Stills &Nash.

Almost as notable as those who played Woodstock are the major solo acts and bands of the late 1960s who remained conspicuously absent from Woodstock. Organizers definitely aimed high, but many of the era's most important rock and folk acts said no. Here's who didn't make the trip to Woodstock, and why.

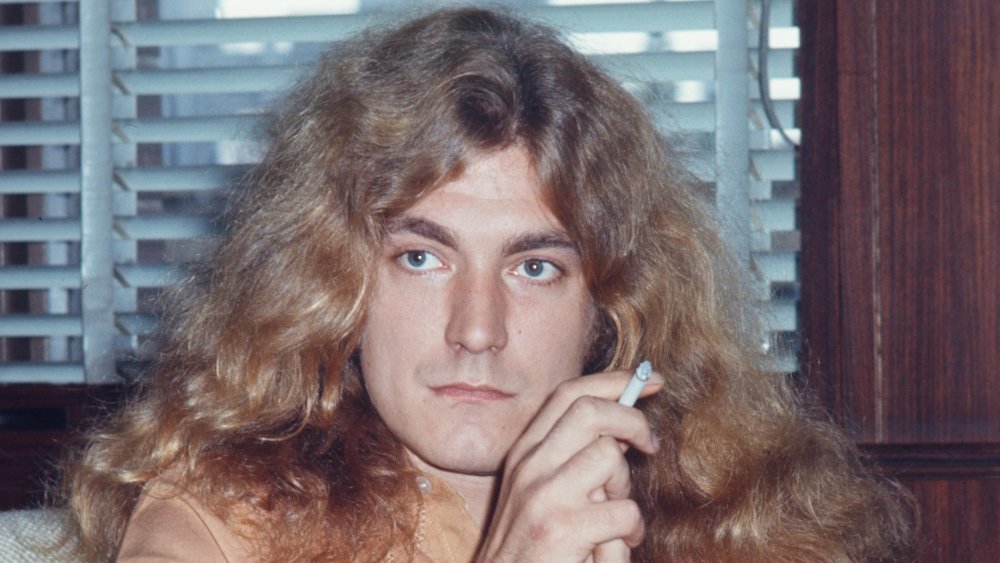

Led Zeppelin was too big for Woodstock

Few bands have ever been as popular or as influential as Led Zeppelin. The foursome of singer Robert Plant, guitarist Jimmy Page, bassist John Paul Jones, and drummer John "Bonzo" Bonham created the blueprint for hard rock with its thunderous, blues-influenced riffs in songs like "Immigrant Song" and "Black Dog" and originated the anthemic, multi-part epic with the immortal "Stairway to Heaven." Five of the band's studio albums rank among the 100 top-selling LPs in American history.

In other words, Led Zeppelin is one of the most singular and monolithic entities in rock history — which is precisely why the band didn't play one of the most singular and monolithic outdoor festivals in rock history. Event planners approached the band's manager, Peter Grant, about a slot. The musicians themselves were interested, as was record label Atlantic Records, but according to Led Zeppelin: The Concert File, Grant passed "because at Woodstock we'd have just been another band on the bill." Instead, Led Zeppelin spent that historic mid-August weekend playing shows — but headlining them at least — in New Jersey and Connecticut.

The Doors just didn't get it

Perhaps no band exemplifies the sound of the late '60s more than the Doors. Its many hits, from "Break on Through to the Other Side" to "People are Strange" to "Light My Fire," suggest drugged-out, harrowing journeys through the human consciousness — that's psychedelic rock at its purest, helped along by Ray Manzarek's mind-bending organ and piano work, Robby Krieger's acrobatic guitars, and the undeniable charisma, stage presence, and sex appeal of lead singer Jim Morrison. Fans never knew what the self-styled rock poet, crooner, and "Lizard King" was going to do — he was arrested for his performances on more than one occasion.

Altogether, that makes for a band that would've fit right in with the half-nude fans and drug-addled bands at Woodstock, yet the Doors were not present at the 1969 festival. The group had already performed at the landmark Monterey Pop Festival in 1967 and thus passed on this new opportunity. "We never played at Woodstock because we were stupid and turned it down," Krieger said during an online chat at the Doors' website in 1996 (via CBS News). "We thought it would be a second class repeat of Monterey Pop."

While the Doors didn't play Woodstock, drummer John Densmore did attend – he's reportedly visible in the 1970 Woodstock documentary during Joe Cocker's set, hanging out near the stage.

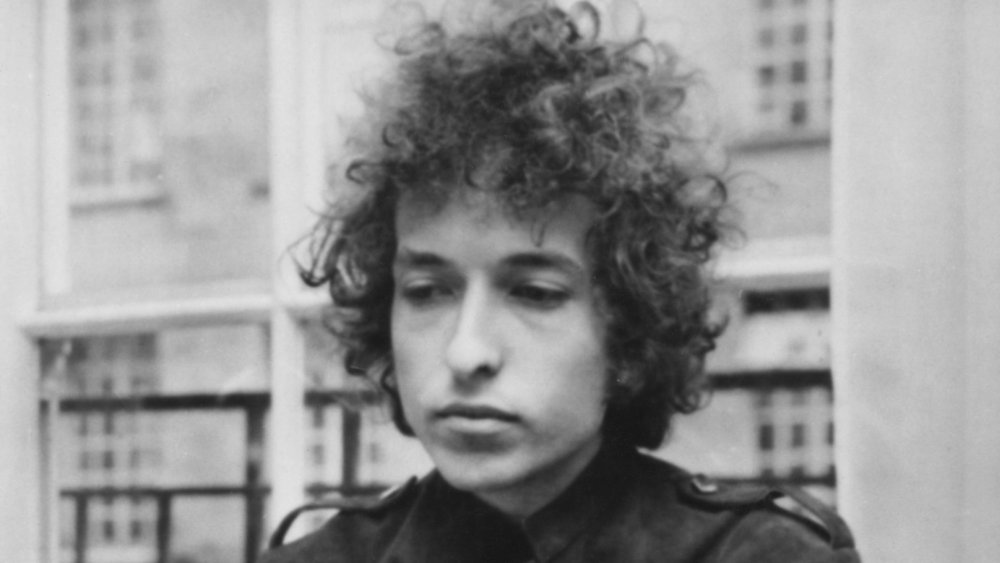

Bob Dylan ran away from Woodstock

Bob Dylan is the towering figure of 20th-century American music. Labeled the "voice of his generation," his poetry set to music, Dylan wrote "Like a Rolling Stone," "Blowin' in the Wind," "Mr. Tambourine Man," "Just Like a Woman," and "All Along the Watchtower," all before he turned 30, and eventually won a Nobel Prize for Literature.

After emerging from the New York folk scene in the early '60s, Dylan was a huge star by the mid-'60s, but by 1969, according to The National, Dylan had largely disappeared from the music scene, recovering from a devastating motorcycle accident in 1966 and experiencing a long, creatively fallow period. By the summer of 1969, the music industry scuttlebutt was that Dylan was ready to make his comeback, and Woodstock organizers figured they had a shot at booking him, especially since it wouldn't have been much of a trip for Dylan — he lived in the artistic enclave of Woodstock, New York, at the time, a mere 50-something miles away from the concert site in Bethel.

In the end, however, Dylan didn't play Woodstock, but he made his return to live performance at another big show just two weeks later: the Isle of Wight Festival in the UK.

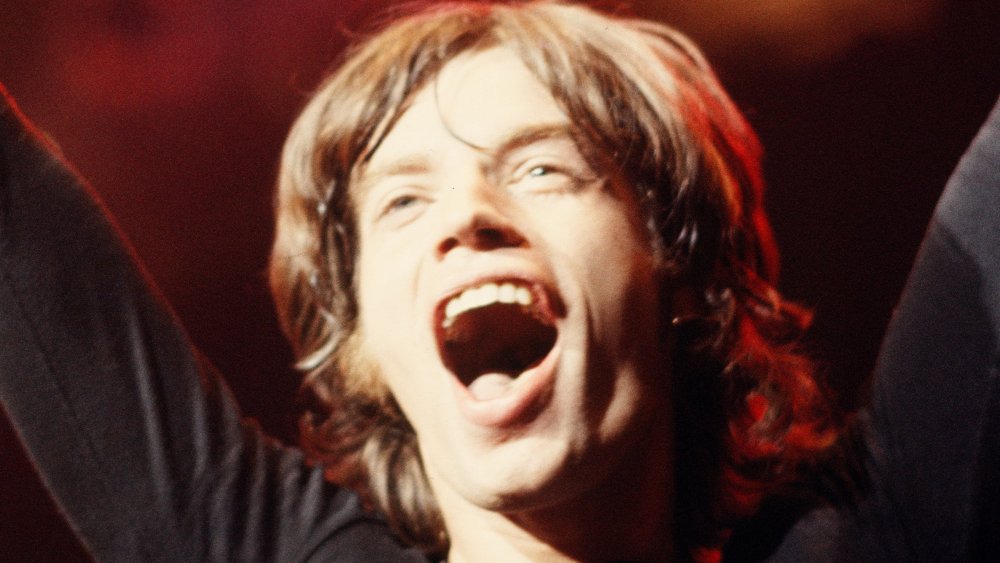

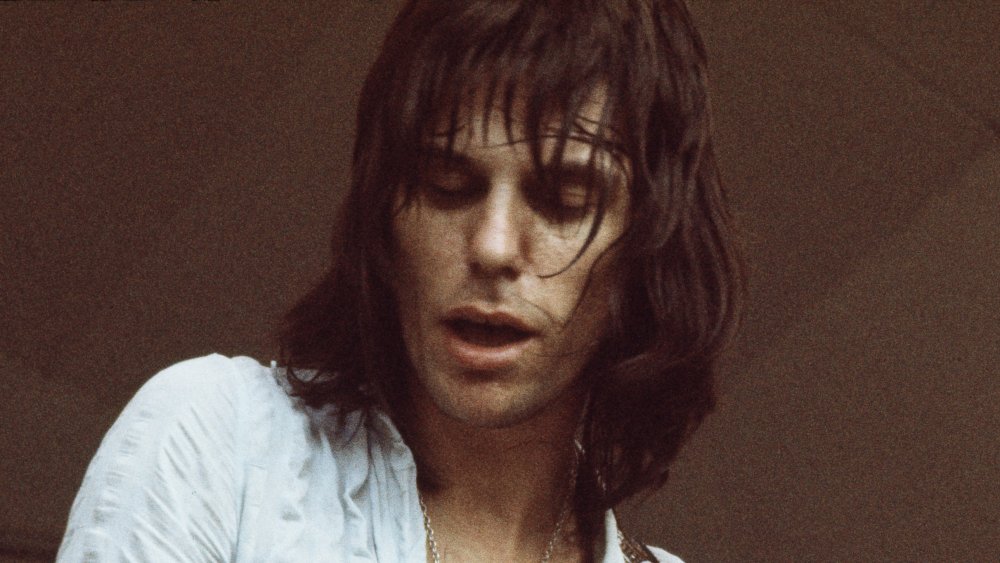

The Rolling Stones were scattered and unavailable

The group predated the psychedelic era of '60s rock heavily represented at Woodstock, but by 1969, the Rolling Stones had thoroughly established themselves as one of the most dominant bands of the '60s. Earlier, the legendary British blues-influenced live act had released its darkest and raunchiest singles to date, "Sympathy for the Devil" and "Honky Tonk Women," respectively, with the latter topping the Billboard Hot 100.

Woodstock organizers naturally extended an invitation to the Stones to perform, but according to Stephen Davis' Old Gods Almost Dead: The 40-Year Odyssey of the Rolling Stones, singer and band leader Mick Jagger turned it down on everyone's behalf. It made logistical sense — Jagger was unable to perform, thousands of miles away in Australia shooting the movie Ned Kelly, while guitarist Keith Richards was preoccupied with the birth of his first child with actress Anita Pallenberg, a son named Marlon, who arrived just five days before the festival began.

Joni Mitchell thought she'd get stuck at Woodstock

Both cerebral and ethereal, singer-songwriter Joni Mitchell is responsible for plenty of fantastic, classic folk-rock songs that helped define the '60s and '70s, including "You Turn Me on I'm a Radio," "Both Sides Now," "River," "Free Man in Paris," "Help Me," "Big Yellow Taxi," and "Woodstock," the first and most famous tune about the important 1969 rock festival and a song that helped make the weekend legendary in the minds of millions. Oddly enough, the person who wrote such an evocative and mood-capturing song as "Woodstock" did not actually perform at or attend the Woodstock Music and Art Fair.

But guess who covered "Woodstock" and made it a top 20 hit: Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, an act that did play Woodstock. According to Goldmine (via Mitchell's website) Mitchell and Nash were a couple at the time, and the singer-songwriter was scheduled to hit Woodstock, too. But then came the reports of the first, problem-plagued day of the festival, and Mitchell, fearing she'd get stranded in upstate New York and be unable to tape an episode of The Dick Cavett Show the following Monday, opted to not make the trip. She'd been overcautious — when she went on Cavett, David Crosby and Stephen Stills made it back in time to appear, too.

The Moody Blues preferred the friendlier environs of Europe

The British art rock-meets-prog band the Moody Blues is best known for "Nights in White Satin," their moody, haunting, atmospheric, and classical music-based breakthrough single off of their 1967 concept album Days of Future Past. The song was a smash hit in the UK but took until 1972 to reach #2 on the American pop chart. Perhaps that and other Moody Blues projects would have received an earlier boost had the band, a known entity to cool, hip rock fans, followed through on its plans to play Woodstock in the summer of 1969.

"Sometimes I wonder if that was a good decision or not," Moody Blues singer Justin Hayward said of his band's decision to not play the show to OnMilwaukee in 2016. "I'm pretty sure we're listed on some of the posters and advertising." At that point, the band was much more popular and established in Europe than it was in the US, and it opted to stick to France and the UK during the Woodstock dates. "We played in Paris the weekend of Woodstock and then returned to the Isle of Wight festival."

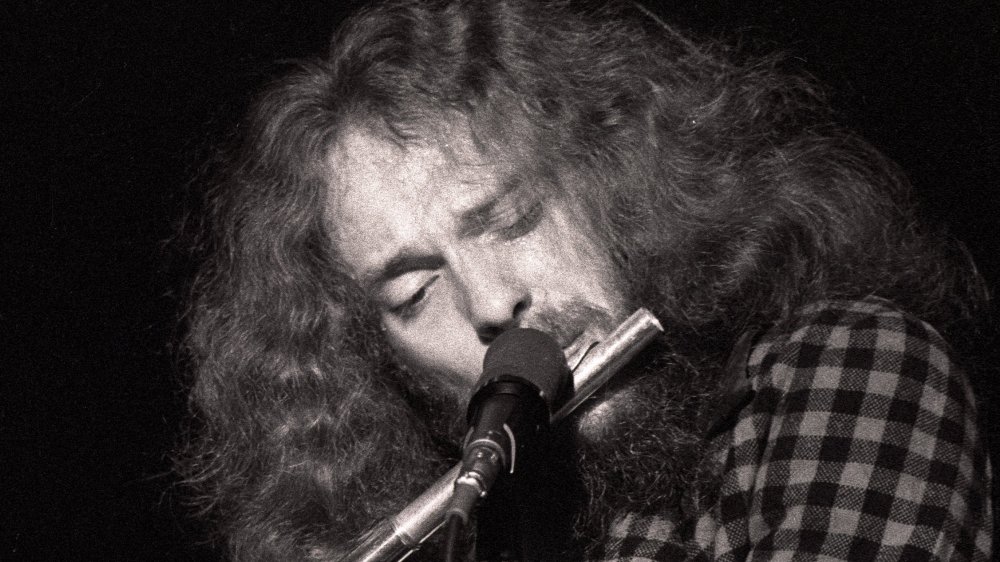

Jethro Tull wasn't down with nudity

By the summer of 1969, Jethro Tull had released one album in the US and was about to release its second, both of them collections of the group's signature combination of blues, jazz, and progressive rock. The band's frontman Ian Anderson is one of the most unique in music history in how he dressed like a wizard onstage, hopped on one foot, and, in addition to singing, also played the flute, a rare rock 'n' roll instrument.

He's also apparently one of the few stars of the '60s and '70s, rock's most hedonistic age, who was averse to chaos and debauchery. Anderson told SongFacts that when his manager proposed Jethro Tull playing Woodstock, he asked what other bands were set to perform. "And he listed a large number of groups who were reputedly going to play, and that it was going to be a hippie festival, and I said, 'Will there be lots of naked ladies? And will there be taking drugs and drinking lots of beer, and fooling around in the mud?'"

Manager Terry Ellis prophetically confirmed that yes, all of those things that would come to define Woodstock were definite possibilities, which is why Anderson said no to Jethro Tull playing the festival. "I don't like hippies," Anderson said, "and I'm usually rather put off by naked ladies unless the time is right."

Jeff Beck wanted to catch a cheater in the act

Jeff Beck is like Forrest Gump, if he were a guitar prodigy who combined blues, jazz, and rock to form a new sound that would help lay the groundwork for heavy metal. Like Jimmy Page and Eric Clapton, Beck was a member of the Yardbirds in the mid-1960s, before he left to form the Jeff Beck Group with future Rolling Stone Ron Wood and singer Rod Stewart. The group toured extensively around the US in the late '60s, with their final road trip taking them through the East Coast.

Stewart wrote in his memoir, Rod: The Autobiography, that the final scheduled stop before the band flew home in 1969 was "some outdoor event or other in upstate New York in August." That festival, of course, was Woodstock, but the Jeff Beck Group wouldn't wind up playing it after all.

Just before its slated Woodstock gig, the band stayed in a hotel outside JFK Airport in New York City, with plans to head up north to play the show, head back to NYC, and fly to London all in one night. The Group pulled out because Beck abandoned them. "Jeff had already flown out on an earlier flight," Stewart wrote. "Apparently he had got wind from somewhere of a rumor, which turned out to be false, that his missus was having an affair with the gardener, so he was quite keen to go home."

Frank Zappa didn't dig the Woodstock scene

Frank Zappa may have looked and acted like a hippie, what with his long hair and lifelong love of provoking and questioning the mainstream with his wild, experimental, and humorous music, but he was anything but. Zappa didn't approve of the hippie generation's love of recreational drugs — he didn't do drugs, didn't allow members of his band, the Mothers of Invention, to do them, and even recorded an anti-speed public service announcement. Nor did Zappa accept whole cloth the ethos of the counterculture — his band's 1968 song "Who Needs the Peace Corps?" is a thorough indictment of hippies.

It's not surprising, then, that Zappa rejected a plea from Woodstock organizers for the Mothers of Invention to play the festival, which wound up being rife with two things Zappa didn't like: drugs and hippies. "A lot of mud at Woodstock," Zappa remarked in the TV special Class of the 20th Century (via RockPasta). "We were invited, we turned it down." Also forcing the band's hand: It had booked gigs elsewhere and played a string of shows in Ottawa and Montreal the weekend Woodstock took place.

Chicago had to honor another engagement

Chicago — the sprawling rock band with a horn section, not the city — has enjoyed many distinct periods with distinct sounds. In the '80s, it was a slick soft-rock band that made radio ballads like "You're the Inspiration" and "Hard to Say I'm Sorry." In the '70s, it was a jazz-tinged rollicking ensemble that recorded classic rock staples such as "25 or 6 to 4" and "Saturday in the Park." And when Chicago started in the '60s, it was a progressive jazz/fusion rock band which released its debut album in 1969 under the name Chicago Transit Authority, winning it a Grammy Award nomination for Best New Artist.

The experimental, forward-thinking group had the musical bona fides to play an event like Woodstock, and Chicago Transit Authority was actually booked to play the famous festival. However, the band had previously signed a contract with Bill Graham to play the legendary Fillmore West in San Francisco, and the famous promoter could schedule the dates for any time he liked. So, he booked Chicago to play in August 1969, the same weekend as Woodstock. That left a slot open at Woodstock, which was quickly filled by Santana ... a group managed by Graham. "We were sort of peeved at him for pulling that one," Chicago singer Peter Cetera told The Spokesman-Review.

Procol Harum had a baby on the way

Procol Harum wasn't like most other rock bands of the Woodstock era in at least two respects. Firstly, an organ figures prominently into the group's fancy, baroque, and erudite sound, especially on its first single and biggest-ever hit, 1967's "A Whiter Shade of Pale," which reached #5 on the US pop chart and went to #1 in the group's native UK. Secondly, Keith Reid enjoyed the full benefits of a band member despite not playing an instrument — he served as Procol Harum's chief lyricist, crafting the words sung by lead singer Gary Brooker.

The group, which only formed in 1967, made such a big splash so quickly that it entertained an offer from Woodstock organizers to play the massive festival. "They really wanted us at Woodstock, they pleaded with us," Brooker said in a 1998 interview. "But we were just coming to the end of a long tour and one of the reasons we were going back to England was that the wife of [guitarist] Robin Trower was going to have a baby and we were going to be there in time for that birth."

And so, Procol Harum returned to the UK. Trower's baby, by the way, arrived two weeks late — so the band could have played Woodstock. "It would have helped us a lot if we had been at Woodstock," Brooker lamented, "but that's the way the dice fall."

Roy Rogers wasn't up for a nostalgia trip

What was supposed to be "three days of love and music" went beyond that time frame due to numerous technical and weather delays. That meant Jimi Hendrix, contractually promised to close Woodstock festival, didn't perform until the extremely un-rock n' roll time of 9:00 AM on Monday morning, to a mostly empty farm. He turned out one of Woodstock's most memorable moments, delivering a free-form, feedback-laden version of "The Star-Spangled Banner," but had festival organizers had their way, Woodstock would have had an extremely incongruous, if wholesome ending.

"We all grew up with Roy Rogers," Woodstock executive producer Michael Lang said at a speaking event in 2009 (via the Washington Examiner), referring to the popular singing cowboy who starred in dozens of movies in the 1930s and 1940s. Lang and his associates really wanted to finish Woodstock with the 57-year-old Rogers crooning his signature song, "Happy Trails." "Roy Rogers turned me down," Lang said. "I wanted 'Happy Trails' to close the festival."