The Tragic Real-Life Story Of Sue The T-Rex

Fossil hunting requires a combination of hard-earned instincts, luck, and optimism. But even the most optimistic fossil hunter wouldn't have dared to dream of discovering what Sue Hendrickson found in the rocks of a South Dakota cliff face one foggy morning in August 1990. Then again, even the most cautious couldn't have predicted what happened next.

Officially named Specimen FMNH PR 2081 but nicknamed Sue after its discoverer, the T-Rex Hendrickson found that day would turn out to be not only the largest but the most complete T-Rex unearthed so far, with about 250 of 380 known bones. The Black Hills Institute team that dug Sue out of the rock it had been in for 67 million years were not certified paleontologists, but they understood the importance of what they had found and planned to share it with scientists and the public. However, their plans were upended when the nickname they'd chosen turned into something closer to a sick joke.

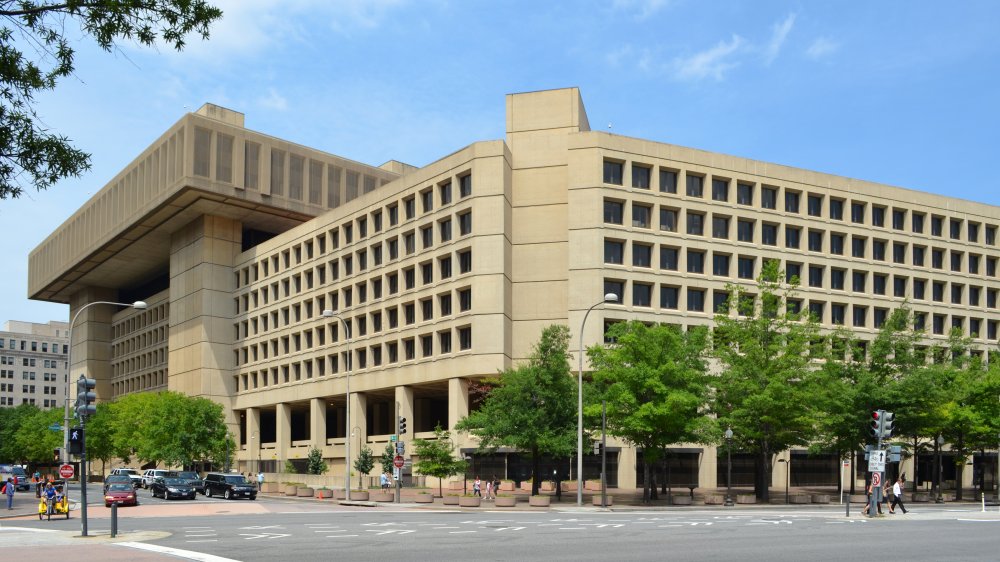

The members of the Black Hills Institute found themselves under investigation by the Department of Justice, which believed that they had stolen the fossil from federal land. The media attention Sue generated pushed the Department and the FBI to look into the Institute's previous collecting and selling habits — and to make an example of them to the rest of their industry. Here's the tragic real-life story of Sue the T-Rex, and the team that found it in the field only to lose it in the courts.

Sue Hendrickson stumbled on a T-Rex

On the morning of August 12, 1990, collector Sue Hendrickson left the other members of her fossil-hunting team to walk alone on the South Dakota ranch where they'd been looking for specimens. The ranch's owner, Maurice Williams, had given them permission to look on his land.

Passing by a cliff, Hendrickson spotted a series of dark shapes in the vertical rock. Her well-trained eye knew better than most what she was looking at: fossilized bones, lots of them, including vertebrae and ribs. She took a fragment back to her team from South Dakota's Black Hills Institute, led by Peter Larson. Larson later told PBS, "I'd never seen the inside of a T-Rex vertebrae before, but I knew that was what I was looking at the minute I saw these things."

He was right. Sue had stumbled on the most intact T-Rex skeleton ever discovered, including a foot-long tooth — the largest T-Rex tooth ever found — and 250 bones. It would eventually stand at 42 feet long — but first, the team had to dig it out of the rock that rose 29 feet above the fossil, in temperatures as high as 120 F.

Over the next 17 days, the team carefully excavated the site until they had the complete skeleton, battling through sections of hard rock. They wrapped the fossils and shipped them to the Institute. They also made a deal with Williams, giving him $5,000 in exchange for the fossil, nicknamed Sue after its discoverer.

Sue the T-Rex had a difficult life

It wasn't easy being a dinosaur — even an enormous, large-toothed, big-clawed predator like Sue. A post-mortem conducted on the fossil many years later found that the T-Rex survived numerous injuries before dying of as-of-yet unknown causes. By the way, despite being named after the woman who discovered her, Sue's sex remains a mystery.

New Scientist reported that the post-mortem found healed fractures on ribs on Sue's right and left sides, indicating that it must have survived two traumatic attacks. Bones in the arms and legs showed signs of healing from infections, and it has some sizable holes in its jaw, which the researchers believe were caused by parasites rather than other dinosaurs.

Sue likely also suffered from a condition many humans are familiar with. Some of its vertebrae have bony growths on them, which indicates back problems, and possibly arthritis. Despite its various injuries and illnesses, Sue is thought to have been the ripe old age of 28 when it died — not bad considering that life expectancy for a T-Rex has been estimated at 35.

On the bright side, Sue may not have been dealing with all this on its own. Peter Larson has suggested that the factor that enabled Sue to survive so long with so many injuries may have been help from other T-Rexes. As he put it at a conference, "complex social behavior such as spousal care." Aw.

The Black Hills Institute is part of the controversial world of commercial fossil hunting

Located in Hill City, SD, (population 1,028), the Black Hills Institute is a fossil collection, fossil shop, and fossil-preparing workshop founded by brothers Peter and Neal Larson in 1974.

Although the Larsons and their team take a scientific approach to hunting and excavating fossils, they are a for-profit business, which makes them controversial in the world of dinosaur digging. (They also have a non-profit museum.)

Some academics argue that amateur fossil hunters and their sometimes legally questionable fossil-finding practices contribute to our collective scientific knowledge. In 1993, an anonymous paleontologist told the New York Times, "the collection methods of many museums and universities would not bear too close a scrutiny ... some of our best specimens have been found by amateurs and commercial dealers. As long as fossil dealers work in scientifically responsible ways, they have a right to make a living."

However, some paleontologists worry that when fossils come with price tags — and when prices are consistently increasing — specimens will end up in private collections where they can't be studied by researchers or viewed by the public. As paleontologist Paul Sereno told the Chicago Tribune, "With prospectors carrying off bones for commercial sale before scientists can study them in the ground, we are losing information on an escalating pace."

Sue the T-Rex required a lot of work

Getting Sue out of the cliff and back to the Institute was just the start of the hard work. Next, the team had to carefully remove the plaster they'd placed around the bones to keep them safe during transport. Then they had to clean the bones: as Neal Larson explained on the Black Hills Institute blog, they'd discovered that the best method involved baking soda and an air abrasion unit similar to the kind dentists use to clean teeth.

Peter Larson put the institute's best preparator, Terry Wentz, to work preparing the fossil. In CNN documentary Dinosaur 13, Wentz recalled, "That was a big job. It took me literally a year just to remove individual bones from around the skull." One of the hardest parts was disconnecting the skull from where it was resting on the pelvis. In the documentary, Wentz described the moment they were finally safely separated as, "probably the highest point of my life."

As Wentz worked, Larson invited scientists and members of the public to watch his progress. According to Neal, he also invited 30 paleontologists to put together a comprehensive monograph on T-Rex, loaned one of the arms to the Denver Museum of Natural History for research, and, in October 1991, presented the team's findings to the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology (SVP). Larson maintained that he had no intention of selling Sue: he wanted her to become the centerpiece of a museum at the Institute.

The legal troubles begin with Sue

It wasn't only scientists — Hill City residents and schoolchildren were fascinated by Sue. The T-Rex and the Institute received a lot of press coverage. This attracted the attention of Vincent Santucci, a paleontologist and geologist for the National Park Service. In Dinosaur 13, Santucci explained that he was outraged watching fossil collectors waltz off with valuable artifacts without, in his view, the proper permissions. He suspected that Larson hadn't got the permissions he needed to claim Sue — and that Maurice Williams hadn't had the right to sell it.

As a member of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe, Williams owned the land Sue was found on. But because it was tribal land, it was held in trust by the Department of the Interior. In a nutshell, Williams had to get permission from the federal government to sell Sue — and he hadn't.

Santucci alerted the Park Service, who alerted the tribe, who felt that Sue belonged to them. And their reservation desperately needed the revenue a T-Rex fossil could generate. In 2000, Steve Emery, the Sioux lawyer who argued the case for the tribe, told the Chicago Tribune, "Our reservation has the 14th- and 29th-poorest counties in the country." The tribe pleaded their case to Acting U.S. Attorney Kevin Schieffer — who authorized an FBI raid.

The FBI takes Sue the T-Rex

On the morning of May 12, 1992, the Black Hills Institute team woke to find FBI agents and National Guard raiding their facility. The agents demanded they turn over Sue, as well as any documents related to it, and any other fossils found on Williams' land.

Peter Larson later recalled that he tried to argue: Sue was 67 million years old and not easily transportable. (Deciding to move an ancient fossil is just one of the most idiotic things the FBI has ever done.) However, it became clear that the agents were willing to escalate the situation if he refused.

As a team from the South Dakota Museum of Geology at the School of Mines — where Sue was to be taken — started to package the fossil, hundreds of local protesters arrived, including children. Experts got involved on the Institute's behalf, but Acting U.S. Attorney Kevin Schieffer, who had authorized the raid, refused to budge. Larson recalled to PBS, "When the trucks drove away ... everybody was just crying ... It was like Sue had died for the second time."

The Institute filed a lawsuit against the Department of Justice, the Department of Interior, the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe, and the School of Mines and Technology, claiming that Sue was their property. Shortly after, Williams jumped into the fray, claiming that the $5,000 he'd received at the dig site wasn't towards purchasing Sue, and therefore he still owned the fossil.

The legal troubles get worse

The lawsuit over who owned Sue was a civil matter. But the media attention the fossil had brought the Institute lit a fire under a criminal investigation that would have even worse personal consequences for Peter Larson and his team.

According to PBS, while supporters continued their "Free Sue" campaign, Acting U.S. Attorney Kevin Schieffer kicked a criminal investigation of the Institute into high gear. The Justice Department wanted to make an example of them, to discourage other commercial fossil hunters who had been taking advantage of lackluster protection of federal property.

The New York Times reported that the FBI conducted another raid on the Institute in June 1993. In November that year, the Department of Justice brought 39 counts and 153 charges against six members of the Black Hills Institute, including Peter and Neal Larson, business partner Bob Farrar, and Terry Wentz. The charges included wire fraud, theft of government property, and making false statements to government agencies.

Peter Larson was charged with conspiracy, obstruction of justice, illegal collection of fossils and theft of government property, and customs violations. They were all related to fossils other than Sue. If found guilty on all 36 counts, it was estimated that he could have been sentenced to 300 years in prison and $12 million in fines.

Who owns Sue?

There was one clear winner in the case of who owned Sue. In 1994, United States District Judge Richard Battey ruled that Williams hadn't had the right to sell Sue to the Institute in 1990 because he hadn't requested permission from the federal government, so the $5,000 purchase was void. This meant that the ownership of Sue went back to Williams. (The actual fossil stayed put in the School of Mines, where it had been for two years.)

This was bad news for the Institute and for the Cheyenne River Sioux. Gregg Bourland, Superintendent of the Cheyenne River Agency, later told PBS, "We have a long-standing history of getting screwed by some unscrupulous type folks around the country, including other governments, so we're pretty much used to this kind of stuff."

Thanks to the criminal case, things got worse for Peter Larson and the Institute. PBS reported that Bob Farrar was found guilty of two felonies, but his charges were later thrown out. Neal Larson was found guilty of one misdemeanor and received two years probation. The Institute was found guilty of four felonies and one misdemeanor. Peter Larson was convicted for theft and retention of government property — both misdemeanors — and of two felonies for failing to declare to US Customs that he was carrying over $10,000 worth of monetary instruments in 1990. In 1996, he was sentenced to two years in prison, a $5,000 fine, and two years supervised release.

Maurice Williams made a lot of money from Sue the T-Rex

After the decision went in his favor, Williams officially requested permission from the federal government to sell Sue, which was granted. In 1996, Sue was moved to Sotheby's auction house in New York, where it was finally reunited with one member of the Institute. Terry Wentz spent 2,000 hours helping to prepare Sue for sale, but it was bittersweet. "I've had a long relationship with her. I may never be able to work with her again," he told the LA Times at the auction.

The auction took place on October 5, 1997. Wentz was joined by someone who'd known Sue even longer: Sue Hendrickson. Like other scientifically minded people, they were concerned that the fossil would disappear with a private collector, along with any hopes of further studying it or showing it to the public.

However, there was good news for Sue supporters, paleontologists, dinosaur fans, and Williams. The LA Times reported that Sue sold to Chicago's Field Museum for a record-breaking $8,362,500, $7.6 million of which ultimately went to Williams after the auction house took its cut. (If you know the incredible story of the 1893 World's Fair, you know the museum has its own interesting history.) The Field Museum had some help from private donors and two unexpected well-known names: McDonald's Corp. and the Walt Disney Co. (Just one of those bizarre things that really happened at Disney.) Both companies were given replicas of the T-Rex.

Peter Larson is still collecting fossils

Larson's appeal to the Eighth Circuit Court against his unusually harsh penalty was denied. He started serving his two-year sentence in February 1996, ultimately getting out in December 1998. He tried to make the best of it. He told Roger Ebert.com, "During bad times, there are some wonderful things that happen as well. Even before I went to the slammer, that's what I wanted to concentrate on." His strange case made him something of a prison celebrity. He taught classes on paleontology and life on Mars, corresponded with people on the outside who were sympathetic to his cause, and made some friends whom he continued to write to after getting out.

However, his release wasn't entirely a celebration. He and his wife, who had written a book about the ordeal with Sue, got divorced shortly after, and he felt, as he told the Telegraph later, "very unhinged for ... six months." It took him a year to get back to feeling close to normal — and he went right back to fossil hunting with the now cash-strapped Black Hills Institute.

The team has since discovered nine more T-Rexes and has even managed to get involved in another drawn-out civil suit. This time it's over the so-called Dueling Dinosaurs — a theropod (possibly a juvenile T-Rex) and an unidentified ceratopsian, which died mid-battle. Larson and his allies lost the original decision over ownership, but as of April 2020, the case was going back to the Montana Supreme Court.

One Sue has become an icon

Like other members of the Institute, Sue Hendrickson was pursued by the FBI, which was looking for evidence that they had illegally taken fossils from government property. She became too scared to use landline phones, thinking they might be bugged, stopped contacting her former colleagues and friends, and dropped out of the limelight. But she continued exploring. In addition to dinosaurs, she specializes in marine archaeology. The LA Times reports that she was part of the team that discovered the San Diego, a Spanish galleon which sank in 1600, and she's also explored Cleopatra's palace and Napoleon's warships, both submerged in the harbor of Alexandria, Egypt.

Sue the T-Rex is a much more public figure. It took 12 museum preparators 30,000 hours to get the fossil ready for display in the Field Museum's huge main hall, which it joined in 2000. But one crucial bit was missing: the incredibly well-preserved skull was too heavy to put on the body. (The bone had been replaced by minerals during fossilization, which were heavier than the original material.) Instead, a cast was used, with the original skull on display above the main hall.

As well as captivating visitors, Sue the T-Rex has helped scientists learn more about T-Rex and dinosaurs generally. In 2018, Sue was moved again, this time into its own private suite nearer the museum's other dinosaurs. Peter Larson still visits Sue whenever he's in Chicago. "I have visitation rights," he joked to the Billings Gazette in 2005.