The Curse Of The Pharaohs Explained

The difference between a zombie and a mummy, besides their wardrobe and mental clarity, is that while both are shuffling corpses, mummies definitely existed in history. You can go to a museum and see one, presuming you go to the right kind of museum. Egyptian mummies are the preserved bodies of people who lived thousands of years ago, some of which are even the bodies of pharaohs and other royalty. It was a process that involves removing organs, embalming the body, and wrapping it in linen.

For hundreds of years, people have believed that disturbing the tombs of these preserved dead can bring a horrible curse upon the intruder as well as anyone they come in contact with. This belief spread like wildfire following the world-famous excavation of the tomb of Tutankhamun. But what is the curse of the pharaohs? How many people has it affected, and what can be done about it? This is the curse of the pharaohs, explained.

Curses were a measure of tomb security for pharaohs

While you can debate whether they actually had any magical effect, the fact is that Egyptians did use curses, especially as security measures on their tombs. As Expedition Magazine explains, these curses were more likely to be present in the tombs of private citizens rather than royalty (presumably because royal tombs had better security), but royal curses are far from unheard of. Most of these curses took the form of threats toward anyone who might rob or otherwise desecrate the tomb.

These curses tend to take the format of "anyone who [does something bad to my tomb], even if they [do or say a lot of things to protect themselves], will [suffer extreme punishment." An abridged example includes, "As for anyone who will: do something evil against this my grave, seize a stone from this my tomb, remove any stone or any brick from this my tomb, enter this tomb in impurity [...] he will be judged regarding it by the great god. I will wring his neck like a goose and cause those who live upon earth to fear the spirits who are in the West. I will exterminate his survivors." Yikes.

Such curses are part of a larger body of magical texts known as execration rituals, which were meant to curse a person or object one found unpalatable, or to ward off harmful spirits.

Pre-Tut mummy encounters

While we can't say for sure whether any ancient graverobbers suffered any ill effects from the cursed tombs of Egypt, the earliest known report of a mummy's curse from the modern era is pretty unambiguous. As recorded by author Leo Ruickbie, the first horrific account of a mummy's magical attack comes from Louis Penicher's 1699 account of a Polish traveler who had taken two mummies from Alexandria. The traveler was subsequently haunted by visions of twin specters who plagued his dreams and was terrified by the increasingly stormy seas on his voyage back home. Apparently, the waves grew worse and worse until the man threw the mummies overboard, at which point the storm abated. Whether or not this story is true, such tales definitely increased popular intrigue around the idea of mummies presenting a supernatural threat.

Interest around mummies and their tombs only increased in the Victorian era, during which period a kind of Orientalist "Egyptomania" swept the empire. In the 19th century, a macabre new fad emerged among the British leisure class: mummy unwrapping parties. While nominally done for science, these spectacles more likely appealed to the more prurient interests of the repressed upper classes as salacious entertainment. At least this was maybe incrementally more acceptable than centuries-old practice of eating mummies for their supposed medical benefits.

Opening Tutankhamun's tomb

The most famous example of a mummy's curse — and the one that kind of drove the idea into the mainstream — is, naturally, associated with the most famous mummy who ever lived (or, uh, died and was then embalmed). According to History, on February 16, 1923, an expedition led by British archaeologist Howard Carter and financed by Lord Carnarvon opened the sealed burial chamber of the teenaged pharaoh of the 18th dynasty, King Tutankhamun, also known as King Tut. Tutankhamun had previously been a little-known and unimportant ruler as far as pharaohs go, but the discovery of his basically intact and undespoiled tomb launched him to a level of celebrity that has hardly diminished in the following century. Carter's discovery likewise kicked off a whole new wave of interest in Egyptology.

It had been in November 1922 that Carter and company first entered the interior chambers of Tut's tomb. There they found treasures that had not been seen by human eyes in over 3,000 years, a rarity as the majority of pharaonic tombs had been looted in previous centuries. In the final chamber, opened in February, Carter found the now-iconic sarcophagus of King Tut, as well as numerous jewels, statues, chariots, and articles of clothing, all of which were carefully catalogued. According to popular legend, however, one other thing was uncovered when the final chamber was unlocked: a deadly curse.

Tragedy strikes the Carter expedition

Despite the fact that King Tut's tomb was not an example of a tomb bearing an inscribed curse on the wall or on any item in its interior, the curse of King Tut is the most famous pharaoh's curse of them all. This was due to the mysterious deaths that befell members of that famous expedition (made even more famous because of the deaths and the alleged curse). Mental Floss lists the various members of the Carter expedition to meet an untimely end after the opening of Tut's tomb in 1923.

The first, and perhaps most shocking, was the dig's financier, Lord Carnarvon, who died mere months after the tomb was first opened when he accidentally cut open a mosquito bite that became infected. A friend of Howard Carter's, to whom he gave a mummified hand as a paperweight gift, had his house burn down and then flood when he tried to rebuild. American railroad executive George Jay Gould died of pneumonia after visiting the tomb.

Lord Carnarvon's half-brother never even visited the tomb, but his blindness, rotten teeth, and death by sepsis are sometimes attributed to being related to an accursed brother. Others supposedly died of murder by smothering, death by burning, and suicide at despair over the curse, among others. Howard Carter himself lived for over a decade after the expedition, but some still attribute his death from lymphoma to the curse.

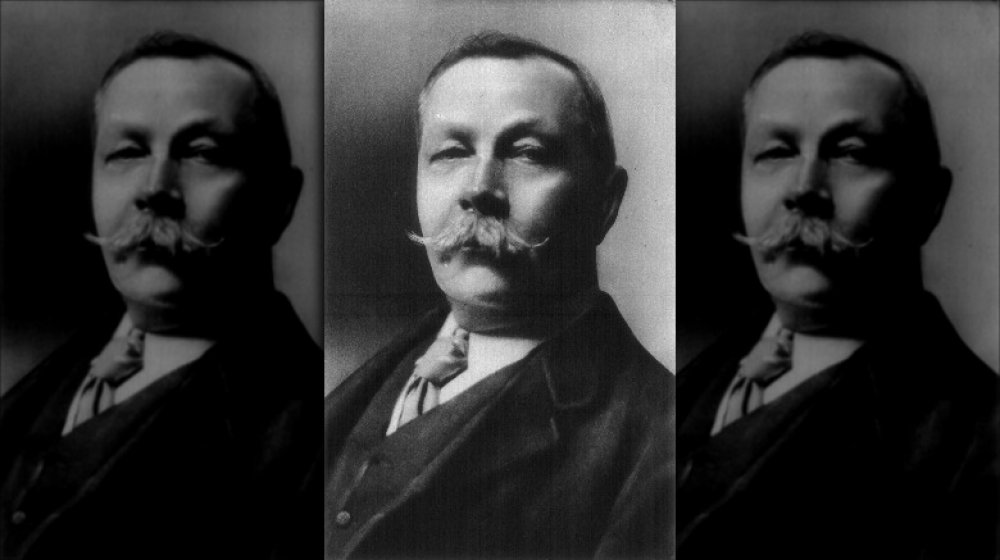

Arthur Conan Doyle helped spread mummy fever

There are a number of people who might be credited with helping to spread the story of the curse of King Tut, as History Answers explains. One culprit was Arthur Weigall, a writer for the Daily Mail who was upset that Lord Carnarvon had sold exclusive story rights to rival newspaper The Times and began to fill columns with whatever Tut "facts" he could, including the story that Carnarvon's pet canary had been killed by a cobra the day the tomb was opened, which he interpreted as an ill omen. Weigall's writing played up the curse angle, which he correctly anticipated the public would eat up, and he later claimed to have predicted Lord Carnarvon's death, saying, "If [Carnarvon] goes down [into the tomb] in that spirit, I give him six weeks to live."

Another person to whom the spread of the curse story can be credited is Sherlock Holmes creator Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, who had a credulous fascination with the supernatural despite being best friends with professional psychic-buster Harry Houdini. Doyle specifically told a New York newspaper that Carnarvon's death was due to an "evil elemental" conjured up by Egyptian priests to protect Tut's tomb. Doyle backed up his conviction with anecdotes about personal friends he believed had been cursed by another mummy. The existence of this mummy could not, alas, be confirmed.

Debunking the curse of the pharaohs

While it is certainly striking to look at a list of those who died or otherwise suffered as a result of the alleged curse of King Tut, it may pay to look at the circumstances with a more skeptical eye. According to History, a study carried out in 2002 by the British Medical Journal looked closely at the survival rates of 44 Westerners who, according to Howard Carter, were in Egypt at the time the tomb was opened (only Westerners were considered as, according to legend, native Egyptians were not affected by the curse). The deaths of the 25 men who were part of Carter's team were compared with those of the Westerners who were not involved in opening the tomb. The study concluded that there was no significant correlation between exposure to the tomb and the average age of death. No one who entered the tomb was more likely to die within 10 years than someone who hadn't.

While a popular theory is that the tomb may have contained mold, spores, or other toxins that infected various members of the team, experts generally don't buy that idea, though mummies and tombs definitely can contain deadly bacteria and mold. The fact is, many of those who died had already been ill. The rest were just people looking for tenuous connections where they don't really exist.

Did a pharaoh's curse sink the Titanic?

Aside from the supposedly cursed tomb of Tutankhamun, one of the most famous stories of a mummy-fueled plague is associated with maybe the most famous disaster of the 20th century: the sinking of the Titanic. The story of the Unlucky Mummy, as it is known, says that four young Englishmen visiting Luxor bought a mummy case containing the remains of an Egyptian princess. One by one, these four men are stricken with disaster: disappearing in the desert, getting shot, losing a fortune, and succumbing to illness.

Eventually, the mummy ends up in the hands of the British Museum. When placed in the Egyptian Room, the mummy began frightening night watchmen with weeping and pounding, throwing other exhibits off shelves, and cursing a child with measles. The museum sold the mummy to a private collector, who found himself equally haunted. This collector eventually agreed to ship the mummy to an American archaeologist in New York. In April 1912. On the HMS Titanic. You get it.

Is this story true? Snopes says of course not. The Titanic's manifests have been closely studied, and there is not a single mummy listed among its various contents. In fact, you can trace back the story of this cursed mummy to the writers William Stead and Douglas Murray, who were inspired by a real coffin lid at the British Museum. The legend got tied to the Titanic after Stead actually died in that tragedy.

The Curse of Osiris

The book The Curse of the Pharaoh's Tombs by Paul Harrison tells the story of British Egyptologist Walter Bryan Emery following the uncovering of a hidden tomb in Sakkara. During this excavation, one of Emery's workers found a statue of the Egyptian god of the dead, Osiris, about eight inches long. The worker gave the statue to Emery, who took it back to his quarters. Emery set the statue on a table and went to take a shower while his assistant waited outside. Soon the assistant hears a worrisome noise and calls out to Emery, receiving no response. The assistant entered the bathroom and found Emery standing paralyzed in the shower. He dragged the professor to the couch and called an ambulance.

Emery was rushed to the British hospital in Cairo, where doctors confirmed that Emery was indeed paralyzed on his right side, unable to move or speak. His wife Mary comforted him, but Emery passed away the next day, March 11, 1971. Cairo newspapers blamed his death on the curse of the pharaohs. Is this story true? Well, Emery was a real British Egyptologist who did excavate a tomb in Sakkara, and he did uncover a small statue of Osiris. He did also collapse suddenly after a stroke and die in a Cairo hospital in March 1971. The details of the story are perhaps exaggerated to draw a connection between the statue and his death, however.

The curse of Tut returns

The legend of the curse of King Tutankhamun, it seems, will never die, whether in reality if you believe in curses, or in popular imagination if you don't. Even decades after the death of Howard Carter, people have continued to believe that the curse of Tut lives on. World-famous Egyptologist Zahi Hawass tells in his book The Golden King of a story spread by a German journalist in a book about the curse of the pharaohs from the 1970s. According to this tale, the journalist met with the Director General of the Egyptian Antiquities Department, Dr. Gamal Mehrez, and asked if he believed in the curse. Mehrez replied that though he had excavated many tombs and mummies, nothing had ever happened to him. According to the journalist, Mehrez was dead the next day.

Popular legend associates Mehrez's death with the movement of some of the treasures of King Tut to an exhibition in England, according to Expedition Magazine. Expedition and Hawass both point out, however, that Mehrez had long suffered from chronic illness. Hawass furthermore reveals that Mehrez actually specialized in Islamic archaeology and had, in fact, never excavated anything from pharaonic times. Other coincidental deaths have likewise been attributed to Tut's curse, including an archaeologist who was hit by a car after protesting the movement of some of Tut's treasures to France, and another director of antiquities killed while crossing the street.

The pharaoh's curse claims a life a year

Zahi Hawass is an Egyptian archaeologist and Egyptologist who was Egypt's first Minister of State for Antiquities Affairs. His 2006 book The Golden King: The World of Tutankhamun discusses his experiences with mummy curses. According to Hawass, when he was young, he was involved in an excavation in the Nile Delta. His job was transporting the excavated artifacts, most of which were from the Greco-Roman era, to Cairo's Egyptian Museum. The very same day that he moved these objects, his aunt died. The next year on the day he moved the artifacts, his uncle died. The following year, his favorite cousin died.

Despite the annual loss of beloved family whenever he transported ancient objects, Hawass does not believe in the curse of the pharaohs, rightly acknowledging that most of the deaths associated with King Tut were foreigners who had nothing to do with the actual excavation. Nevertheless, in his earlier book The Valley of the Golden Mummies, he relates the story of how after excavating the mummies of two children at the Bahariya Oasis, he found himself haunted by the children in his dreams. After months of sleepless nights and a particularly frightening nightmare in which the young girl mummy reached out to strangle him, Hawass concluded that the children needed to be displayed with their father, also a mummy. After the family was reunited, the nightmares stopped.

Tomb raider receives pharaonic revenge

Not everyone who gets stricken with a mummy's curse is an archaeologist. In some cases, the accursed in question isn't looking to put artifacts in a museum but rather money — or a cool trinket — in their pocket. Such was the case in 2004 when a German tourist visited an Egyptian tomb and decided to stroll out with a pharaonic carving he definitely had not walked in with. According to the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, once the man returned home to Germany with his illicitly obtained souvenir, he began experiencing a number of horrific conditions, including paralysis, nausea, fevers, chills, and even cancer, to which he eventually succumbed by 2007.

At that point, the man's stepson decided the only way to rid his family of this curse was to return the object to its place of origin. As such, he sent the carving to the Egyptian embassy in Berlin, who sent the object back to the Supreme Council for Antiquities for authentication. The artifact was sent along with a note from the stepson apologizing for the theft and his account of his stepfather's death, which he attributed to the curse of the pharaohs. According to the note, the stepson hoped that returning the carving would atone for his stepfather's crime and allow his soul to rest in peace. That, presumably, is up to Osiris.

The pharaoh's curse as genre

While the rumors of mummy's curses were fueled by real-life deaths and a large number of sensationalized news reports looking to sell papers, popular fiction also played a role in the dissemination of the idea that a mummy might kill you with magic. Sparked by the Victorian fad of Egyptomania and mummy unwrappings, a number of horror and science fiction writers started incorporating mummies and curses into their stories. In 1827, English author Jane Loudon, an early pioneer in science fiction and Gothic horror, wrote a three-volume work called The Mummy!: A Tale of the Twenty-Second Century, in which a mummy is brought back to life in the year 2126. The book is kind of an anti-Frankenstein, in which an eloquent mummy makes friends and credits God with his existence.

More on the horror end of things, Louisa May Alcott (yes, that Louisa May Alcott) wrote a short story in 1869 called "Lost in a Pyramid, or The Mummy's Curse," in which death follows a young man who, while lost in a pyramid (like the title says), burned a mummy in hopes that the smoke would bring help. Even Gothic master Edgar Allan Poe got in on the hot mummy action in 1845 with a satirical story, "Some Words With a Mummy," in which some very serious Victorian gentlemen revive the mummy Allamistakeo by zapping it with electricity.