The Bizarre History Of The Statue Of Liberty

"Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free." This line may be the single most recognizable phrase we identify with the Statue of Liberty. But a slew of assumptions has been made about the history and significance of the statue. Most people cite Lady Liberty as the first thing immigrants witnessed as they approached Ellis Island by boat to enter the United States, coupled with the famous poem by Emma Lazarus. The lady with the torch and crown welcomed weary travelers in search of a better life for their families. That is eventually what Lady Liberty would come to emblemize, but oddly, the subject of immigration to the United States never came up during the statue's inception.

Of course, the Statue of Liberty can hold various meanings to different people. There is no right answer. Here are some strange facts about the lure and evolution of the statue that you may find surprising. To begin, we must travel across the Atlantic to France.

The Statue of Liberty was a beacon of hope for global democracy

Édouard de Laboulaye, known as the "Father of the Statue of Liberty" hoped the gift of Lady Liberty would inspire the French to fight for their own democracy in the face of a repressive monarchy under Napoleon III. He also hoped that the gift would secure the French-American alliance. As the president of the French Anti-Slavery Society, de Laboulaye was a staunch supporter of Abraham Lincoln's emancipation efforts, as well as the passage of the 13th Amendment. When his hopes became a reality, and slavery was successfully abolished in 1865, he began working on his proposal for the statue. Finally, in 1875, the announcement of the statue was made, which would be financed by the French. The Americans would then be expected to pay for the pedestal. The full name of the statue was, and still is, Liberty Enlightening the World.

The statue's initial purpose was to celebrate the viable democracy America had built in the aftermath of the Civil War. It was scheduled to be revealed for the centennial of the Declaration of Independence in 1876, but wouldn't be finished and presented until 10 years later, on October 28, 1886, when then-President Grover Cleveland dedicated it to the Franco-American alliance on the Upper New York Bay, now known as Liberty Island.

The Statue of Liberty was originally a symbol of freeing slaves

It's assumed by most that Lady Liberty represented a celebration of immigration. But history has since proven that the gift was originally meant not only to highlight enlightenment and democracy but to symbolize freedom from slavery.

Laboulaye organized a meeting with French abolitionists in 1865 at his home in Versailles. According to Edward Berenson, a history professor at New York University, "they talked about the idea of creating some kind of commemorative gift that would recognize the importance of the liberation of the slaves." The Statue of Liberty was modeled after the Roman goddess Libertas, who traditionally wore the type of cap worn by freed Roman slaves.

But Laboulaye's original vision, along with commissioned statue artist Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi's designs, seemed to get lost as the years of fundraising for the statue continued. Black newspapers criticized the symbolic gesture as empty and hypocritical. By 1886, when the statue finally made its debut, civil rights protections were already being rolled back, and the Jim Crow era was on the horizon.

A series of retrieved sketches and clay models created between 1870-1871 shows broken chains at the female figure's feet, with an additional broken chain in her left hand. The final result still shows a small broken chain at her feet, partially covered by her ensemble, but it often goes unnoticed.

The Statue of Liberty acted as a lighthouse for 16 years

From 1886 to 1902, Lady Liberty was intended to have a practical purpose as well as a symbolic one as a lighthouse. Ultimately, it was a pretty useless one. The Statue of Liberty was, however, officially under the operation of the Lighthouse Board for a brief stint.

Residing on what was then Bedloe's Island, the Statue of Liberty was within eyesight of every ship that arrived in the New York Harbor. It was originally intended to have floodlights installed on the balcony of the statue's torch, but those plans were denied by the Army Corps of Engineers for fear that the bright lights may blind ship captains nearby. The portholes, however, in the torch, allowed for lights to be placed inside of it.

Although it was technically available for use as a lighthouse immediately, some extra engineering was commissioned by the American Electric Manufacturing Company in 1890, where a dynamo generator was added, as well as 11 new lamp houses for the lights around the base of the statue. An incandescent electric light plant was also added to the statue's interior.

Lady Liberty's torch could be seen standing 305 feet above sea level. Its nine lamps could be seen from only 24 miles out to sea, which made it a very dim lighthouse. Though upgrades were attempted through the years by the Lighthouse Board, the statue never fully succeeded as a working lighthouse.

The Statue of Liberty came to New York in hundreds of pieces

The statue's 350 copper pieces were transported to America in 214 crates on the French ship Isere, which almost sank in stormy seas. The statue's parts alone took long to ship across the Atlantic and took a lot longer to fully assemble.

A decade before she would be fully constructed, her arm and torch were displayed in Madison Square Park, and at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia to secure further funding. Believe it or not, building Lady Liberty cost what equates to around $5.5 million today. And that was on the American side. The French paid millions of francs more to have it constructed as a diplomatic gift.

Luckily, the instructions were a little better than the likes of an Ikea bookshelf. Sculptor Auguste Bartholdi devised an extensive and unique assembly plan. Each piece would be secured within an iron framework, supported by wooden beams. It took four months alone just to hoist her onto her mighty pedestal. It's no surprise given she weighs 204 metric tons, and wears a size 879 shoe.

It isn't easy being green

Lady Liberty is so well-known and beloved, her color is in a category of its own. But the Statue of Liberty was originally made of copper with the thickness of about two pennies combined. It sounds thin, but the copper is actually incredibly strong. If the Statue of Liberty was melted down, it would equal the copper of 30 million pennies. But copper eventually decays due to oxidation. A thin layer of copper carbonate called a patina forms over time. But don't worry, this layer ultimately protects her from further corrosion.

Her blue-green color is due to chemical reactions between metal and water. It was originally a reddish-brown, much like the color of a penny. Her frame is iron, and her torch flame is coated in gold leaf, but the rest of her is pure copper.

Where did all that copper come from? After all, the statue's exterior required 31 tons of it. It was mostly donated by a copper magnate, Pierre-Eugène Secrétan, who likely retrieved it from a mine off the coast of Norway. Lady Liberty truly is a global world wonder.

The Statue of Liberty is drenched in symbolism

From head-to-toe, Lady Liberty represents a plethora of philosophical, political, and historical significance on a global scale. The very pedestal she stands on is a row of shields, representing the 40 states of the Union at the time. And speaking of Lady Liberty's global credentials, her crown of rays represents the seven seas and seven continents of the world. The tablet she holds is an inscription of the Roman 4th of July — JULY IV MDCCLXXVI, which of course was the day America declared independence from Great Britain.

The statue purposefully faces the entrance of the port of New York, which was the gateway to America when it was assembled. She also notably faces Europe and her French creators. A copy of the United States Declaration of Independence resides on a hollow stone at her base, along with a safe containing memorabilia belonging to people who visited her in 1886 near the front of her pedestal.

And of course, let's not forget that broken chain at her feet.

Lady Liberty's morbid side

In May of 1929, a young man tragically plunged more than 200 feet to his death from the top of the Statue of Liberty, landing on the pedestal. It was the first suicide on record at the monument. Unfortunately, it wouldn't be the last.

In June of 1997, a 30-year-old man jumped from 80 feet to his death. According to a stander-by, Sergeant Ross, Elhajo Malick Dieye grew upset that the stairs to the crown were closed. He then told Ross that the FBI was after him. When Ross moved toward him, the man "rushed toward the exit and over a wall." Dieye was a Senegalese immigrant who lived in Queens.

Two souls ultimately committed suicide and multiple others have made attempts atop the statue. It's one reason why the stairs leading to her crown are now permanently closed to the general public. Not only has her crown proven to be a liability, but Lady Liberty herself is apparently hit by approximately 600 bolts of lightning a year since being built!

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

A brush with destruction during World War I

In 1916, the Germans set off an explosion that caused the Statue of Liberty to sustain minor damage in what is now known as the Black Tom bombing. Lady Liberty's arm suffered the brunt of the attack, and it cost $100,000 to repair her.

Black Tom was once a small island that happened to be the home of the "single most important assembly and shipping center in America for munitions and gunpowder being sent to the Allies" during World War I, per History. While most arms dealers sold only to their allies back then, it wasn't illegal to sell munitions to enemies, and at the time the United States was officially neutral.

In what was initially an accident, the first pair of explosions from the island killed at least five people, including a baby who was thrown from his crib in Jersey City. The explosions caused millions of dollars in property damage. Lower Manhattan experienced damage as well with thousands of windows shattered, and shrapnel pock-marked the Statue of Liberty. She was clearly built for battle (and lightning strikes) and withstood the incident. Black Tom's site is part of Liberty State Park in New Jersey today.

Lady Liberty's significance during World War II

On May 8, 1945, World War II was officially over after the announcement was made that Germany had declared unconditional surrender. Countries of the western world celebrated in the streets en masse. On the historic V-E Day of 1945, a 15-ton replica of The Statue of Liberty was erected in Times Square for the celebration. Filled with hundreds of happy people from morning to evening, withstanding rain at some point, they watched as the replica of Lady Liberty "bathed in light after sunset" according to the New York Times, joining with the lights of Broadway for one special night. "The dimout and the brownout of the 'Great White Way' have been replaced once more by the bright lights of victory," wrote Associated Press journalist Matty Zimmerman.

The original Statue of Liberty also joined in the night's celebration. During the war, her torch and floodlights went dark with the exception of the D-Day invasion of Normandy in 1944, and on V-E Day. On D-Day, her crown lights flashed dot-dot-dot-dash, which means V for Victory in Morse Code, as her torch blazed on in New York Harbor. On V-E Day, her lights reappeared, while two American servicemen stood guard at the base of the statue through the night.

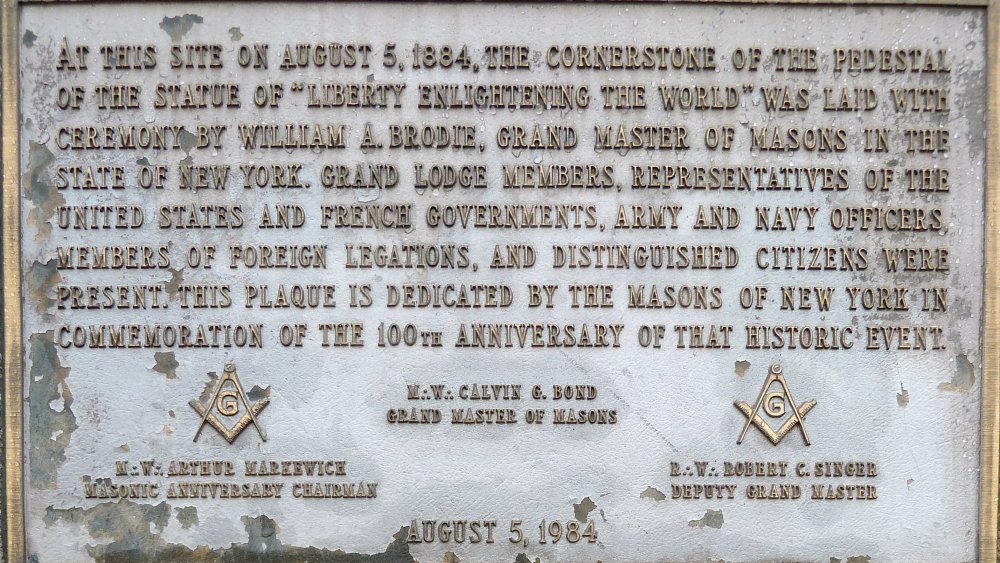

The Masonic Influence

The Freemasons seem to show up everywhere in theory, but where the Statue of Liberty is involved, there's actual proof the secretive fraternity had some sway. The Statue of Liberty was even said to have been presented originally as a gift from the French Grand Orient Temple Masons to the Masons of America.

For those who aren't knee-deep in Masonic knowledge, the Freemasons originated in the Middle Ages but took a legitimate hold on early American history. Many of the Founding Fathers, including America's first president, George Washington, identified as one. In fact, he earned the title of Master Mason, which is the fraternity's highest basic rank.

There are a ton of Masonic references on Lady Liberty, such as the statue's cornerstone plaque, which boasts a square and compass. Inside the cornerstone is supposedly a time capsule, including a copy of the US Constitution, George Washington's Farewell Address, and a list of parchment naming the Masonic Grand Lodge (governing) officers.

She holds what many consider to be the Masonic "Torch of Enlightenment," which was also known by the Illuminati Masons in the 1700s as the "Flaming Torch of Reason."

The Statue of Liberty was almost a Muslim woman

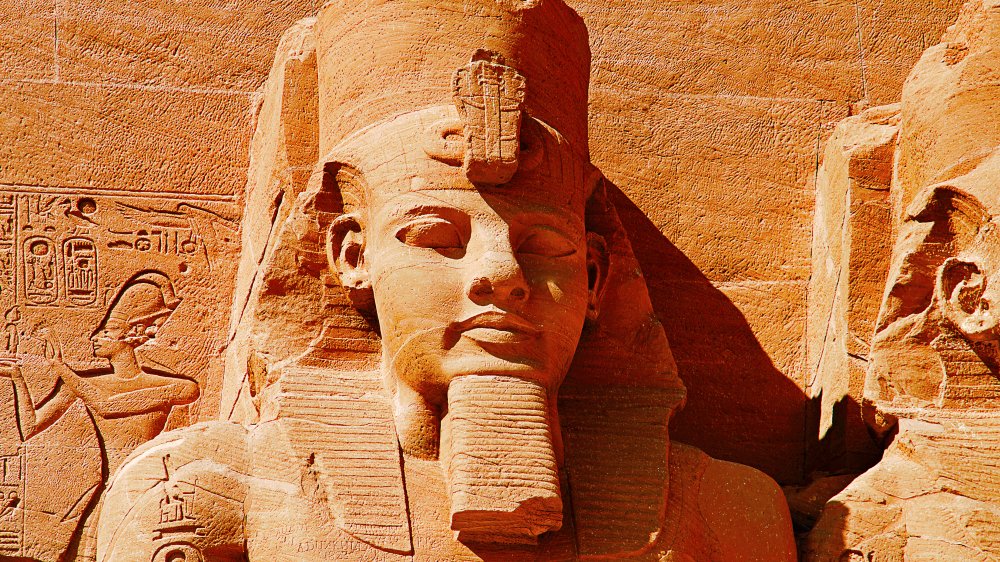

Lady Liberty's designer, Bartholdi, visited Egypt in 1855. He became fascinated with Nubian monuments at Abu Simbel, where he drew inspiration for his statue. We can see the resemblance in style if we observe monuments like Pharaoh Ramses II, particularly the eyes, lips, and chin. Channeling his love for ancient architecture, Bartholdi had what the National Park Service notes as a "passion for large-scale public monuments and colossal structures," per Smithsonian magazine.

Bartholdi regarded Egypt's ancient statues so much that in his early design days, he envisioned his creation being revealed at the inauguration of the Suez Canal in 1869. The statue was originally meant to stand 86 feet high, "taking the form of a veiled peasant woman," according to Statue of Liberty scholar, Barry Moreno. Early models were entitled Egypt Carrying the Light to Asia.

The statue's final female form actually takes after the Colossus of Rhodes in Greece, which is one of the original Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

The New Colossus and the Statue of Liberty

From the colossus of Greece came "The New Colossus," which Emma Lazarus so poignantly named her famous poem. We've all heard lines from Lazarus' sonnet written in 1883. But how and why was it written? After all, Lady Liberty's creators never initially intended it to be a symbol of immigration, which is the unmistakable theme of the poem. Ellis Island wouldn't even open its doors to immigrants until 1892.

Lazarus was a 34-year-old writer, political activist, and native New Yorker. She was also the daughter of a wealthy Jewish family and became increasingly concerned about Jews being persecuted in Russia. Lazarus wrote the sonnet after persuasion from friends to raise money for the Statue of Liberty's pedestal, as part of a campaign led by newspaper mogul Joseph Pulitzer. What's most interesting about the conception of her poem, however, is that it was written before the statue ever saw the light of day and before anyone knew what it would come to represent.

In a way, Lazarus was manifesting what America could be, but she was anything but naive about the "Mother of Exiles" she wrote about in her poem. The ominous geopolitical climate at the time was ever-evolving, setting the stage for what would soon become World War I. The poem was not an instant success, and Lazarus tragically died at the age of 38. She would never witness the poem being installed on a bronze plaque of the Statue of Liberty's interior wall in 1903.