The Worst Election Day In United States History Was 100 Years Ago

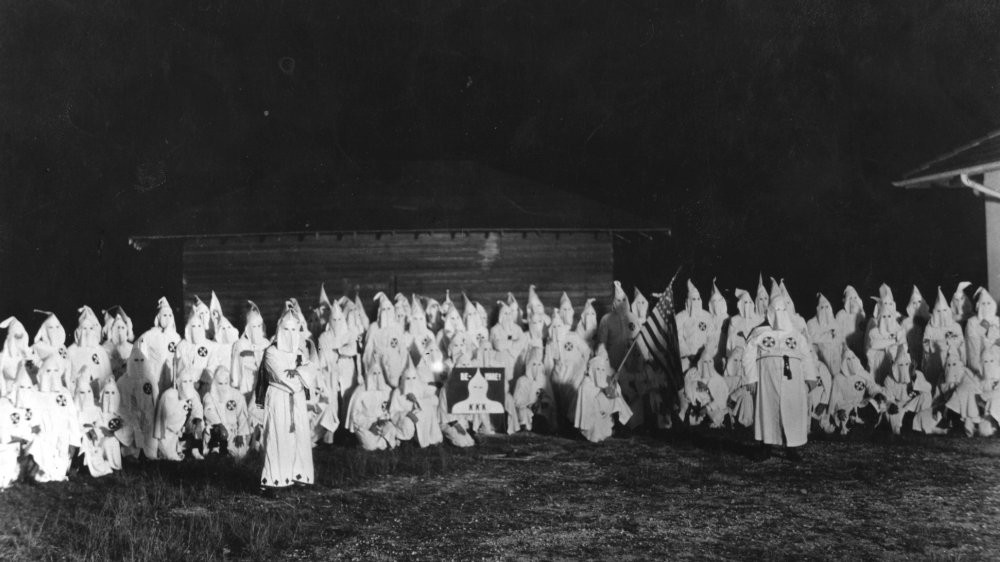

Despite the fact that voting is a constitutional right in the United States, many people of color throughout history have been murdered for exercising and encouraging that very right. Voter suppression and voter intimidation came in many different forms, ranging from the Ku Klux Klan dropping cards in Black neighborhoods via airplane over Oklahoma City in the 1920s, to Klan officials being on hand to "take careful note of the voting procedure at all polling places."

One of the most horrific and brutal outcomes of the KKK's efforts of voter intimidation occurred in 1920 in Ocoee, Florida. After witnessing the efforts of organizers to register Black voters, the KKK repeatedly tried to scare and suppress citizens from voting on Election Day.

The day of the election, only one Black citizen in the city of Ocoee, July Perry, managed to cast his vote. For that act, he was brutally lynched and white civilians burned Black neighborhoods to the ground. Over several days, every Black resident of Ocoee was driven out of the town and Ocoee became yet another "sundown town" in the United States. Ocoee wouldn't have a single Black resident again until 1981.

Voter suppression and voter intimidation remain critical issues in the 2020 election and in order to effectively address them, their legacy must be understood. The worst election day in United States history was 100 years ago and here's the story of what happened.

Ocoee, Florida before the 1850s

Before Europeans invaded Florida in the 16th century, there were hundreds of thousands of Native people living in the area in over twenty different groups. By the 1700s, several Southern Georgian and Northern Floridian Native tribes joined together to fight against the European invaders. This group was collectively called Cimarrones, from which the name Seminole evolved.

This alliance included the Miccosukee, Oconee, and Creek tribes, and although today Seminole people speak multiple languages and have different cultural backgrounds, they are considered a united sovereign nation. Many people who escaped enslavement also found refuge with the Seminole tribe, per the Orlando Sentinel.

According to the Seminole Tribe of Florida, the United States government attempted to relocate the Seminole people first in the 1830s. But while the Cherokees "Trail of Tears" was a single, horrific moment, the forced relocation of the Seminole people lasted twenty years. During this time many were hunted down and forced away from their ancestral lands. The Department of the Interior wouldn't set aside land for a Seminole reservation until 1907.

The City of Ocoee

By the 1850s, the first white settlers were being recorded on tax rolls and censuses. According to OPPAGA, James D. Starke was Ocoee's first white settler and the 1855 Orange County tax roll lists him as an owner of enslaved people and a physician. After the Civil War ended, former Confederate captain Bluford M. Sims, also a former owner of enslaved people, settled in the area.

During the 1880s, Black people also started moving to Ocoee. By the 1920s, almost half of the 1,000 residents were Black and two distinct Black communities had evolved in Ocoee. The Friendship Baptist Church, founded in 1896, fostered what was known locally as the Baptist Quarters in the south. And in the north, the Methodist Quarters was centered around the Ocoee African Methodist Episcopal Church, which hosted its first services in 1890 (founder Richard Allen, pictured).

Since it was in the south, Ocoee was subject to the Jim Crow legislation that reigned supreme at the time. But despite white people's efforts to keep Black people from their constitutional rights, leading up to the 1920 election Black people were registering to vote in record numbers. This was seen by many white supremacists as an affront to the balance of power.

Registration of Black women voters in the 1920 election

In the weeks leading up to the election, Black people across Florida had simultaneously been mobilizing voter registration efforts. And the 1920 election was especially special because it was the first one where women were enfranchised to vote. As a result, Black women's organizations all over the country were mobilizing. And thousands of Black servicemen coming back after serving in World War I were also eager to cast their ballots after putting their lives on the line for their country, according to Vice.

And after Democratic President Woodrow Wilson had expressed support for Jim Crow laws, the Republican Party also sought to mobilize Black voters for the 1920 election. Judge John Moses Cheney, who was running for a Senate seat, set out to register Black voters in Florida, as did William R. O'Neal, an Orlando attorney. Cheney's effort was supported by Mose Norman and July Perry, two prominent Black businessmen who lived in Ocoee.

But this attempt to support Black voters led to an accelerated resurgence of the KKK. According to Walterboro Live, the KKK warned the Black community that they would not be permitted to vote. In the end, July Perry was the only Black person from Ocoee able to cast their vote on November 2, 1920. And for that, he and many others were murdered.

Who were Mose Norman and July Perry?

Both Julius "July" Perry and Moses "Mose" Norman were leaders in the Ocoee Black community. Norman was a member of a local fraternal lodge and was one of the first people in Ocoee to own a car, and Perry was a labor leader and a deacon in the church. According to the Orlando Sentinel, Norman and Perry each owned a small orange grove and controlled practically the entire labor market for black farmworkers.

Both were also quite well-off, and many whispered afterward that Perry was targeted for his wealth. According to Zora Neale Hurston and a History of Southern Life by Tiffany Ruby Patterson, the whispers were right on the money, so to speak. Norman was also "unpopular with the whites because he was too prosperous; he owned an orange grove for which he had refused offers of $10,000 several times."

According to Walterboro Live, both Norman and Perry worked towards encouraging Black people to register to vote and even offered to pay poll taxes for people who couldn't afford to themselves. Poll taxes were one of many forms of voter suppression, aimed at keeping people from voting.

The KKK ramps up voter intimidation during the 1920 election

The KKK quickly noticed and sought to suppress the efforts of the Black community and Republicans. According to OPPAGA, William O'Neal received a letter from the Grand threatening him if he continued speaking to the Black community and "explaining to them just how to become citizens, and how to assert their rights."

According to the Orlando Sentinel, the horrifying letter from the KKK ended, "We shall always enjoy WHITE SUPREMACY [sic] in this country and he who interferes must face the consequences." A mockup of a lynched Black man was also hung up as a demonstration of what would happen to any Black person who attempted to vote.

The KKK also staged multiple rallies. According to the Zinn Education Project, on November 1st, the day before the election, the Klan continued to march around Ocoee "late into the night" and yelled through megaphones that if any Black person dared to vote that "there would be dire consequences."

Local officials also joined in with the Klan in an effort to stop Black voters from casting their votes. One part of the plan involved setting up "armed KKK members across the street from the polling station." Some were even told to confirm their registration with R. C. Bigelow, the notary public. But as part of the coordinated effort, Bigelow had already left town on a fishing trip.

Mose Norman attempts to vote in the 1920 election

On November 2, 1920, July Perry ended up being the first and only Black person in Ocoee who was able to vote, getting his vote in before vote suppressors were able to sufficiently mobilize. Other Black people who tried to vote were blocked from entering their polling places. Many were threatened by violence or, when they were able to make it into the polling place, found their names "mysteriously" missing from registration lists.

According to OPPAGA, when Mose Norman went to vote, he was told that he hadn't paid his poll tax. Undeterred, he drove to Orlando to meet with Judge Cheney about his options. Cheney told Norman to go back to the polling place and write down the names of anyone who prevented him or anyone else from voting.

Upon returning to the polling place, Norman was once more denied the right to vote. He demanded the poll workers' names, famously exclaiming, "We will vote, by God!"

One account claims that local law enforcement noticed a shotgun in Norman's car and confiscated it before letting Norman go. Another version recounts that a group of white civilians found the gun in Norman's car and assaulted him. But in both versions, afterward, Norman stopped by Perry's home on his way fleeing Ocoee. It's believed that Norman lived out the rest of his life in New York, but he was never heard from again.

A lynch mob seeks out July Perry on election day

After the incident at the polling place, Orange County Sheriff Deputy Clyde Pounds deputized several white Ocoee residents and the mob was tasked with arresting Norman and Perry. By this point, Norman had already left Ocoee, so the mob went to Perry's home.

At the time, Perry was home with his wife and daughter while his sons were out of the main house. They knew what was coming and Perry was determined to defend himself. According to Orlando Weekly, after the mob surrounded the house, shots were fired. In the ensuing gunfire, Perry, his wife, and his daughter, all sustained heavy injuries. Out of the attacking mob, Leo Borgard and Elmer McDaniels were shot to death and several others were wounded in their attempts to break into the house.

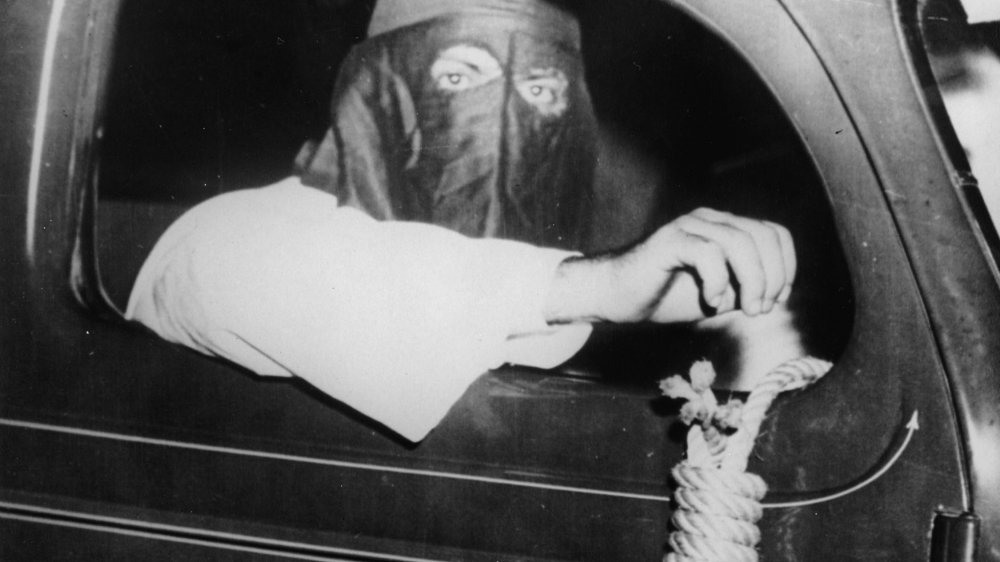

Despite his injuries, Perry fled into a nearby cane field. According to Zora Neale Hurston and a History of Southern Life by Tiffany Ruby Patterson, the mob hunted for Perry until his capture at dawn, after which he was taken to an Orlando jail. But the white supremacists weren't interested in any consideration of justice. As Zora Neale Huston recounts, after sun-up, "the mob stormed the jail and dragged him out and tied him to the back of a car and killed him and left his body swinging to a telephone post beside the highway ... That was the end of what happened in Ocoee on election day, 1920."

Ocoee burns throughout the night after the election

The assault wasn't limited to Perry's lynching. During the search for Perry, more than 200 white civilians showed up to "patrol," during which they burned the town's two Black neighborhoods. At least 20 houses, two churches, and one fraternal lodge were burned down.

People's houses were set on fire and the white mobs shot at those who tried to escape, driving people back into the flames. Countless people were tortured, like James Langmead, for refusing to leave the land he owned. According to "Dead Men Bring No Claims" by Melissa Fussell, no one knows exactly how many people died that night. The lowest reported number was three while the highest ranges from 60. According to "Election Day in Florida" by NAACP undercover investigator Walter F. White, one man proudly claimed to have "killed seventeen myself." Sickeningly, after the embers had burned out, members of the mob even "rushed in and sought gleefully the charred bones of the victims as souvenirs."

According to The Weekly Challenger, the massacre lasted until at least 4:45 a.m.

People are pushed out of Ocoee after the election

The only building left standing after the 1920 election was a schoolhouse that was county property. In the morning, a Black undertaker named J. B. Stone took Perry's body down off the telephone pole, per Medium. But when the white residents of Ocoee found out that he'd done this, they warned him that if he ever took down another lynching victim, "they would do the same to him."

According to Tiffany Ruby Patterson, while Perry's death certificate initially listed his cause of death as "by being hung," sometime later someone added, "not by violence caused by racial disturbance."

For nearly a week after the elections, the KKK and white mobs "set up an embargo around the town. No one was permitted to enter or leave without their permission," as reported in Medium. Black people who'd fled were kept from returning to their homes while those who'd survived the massacre were given one day to collect and bury the remains of the dead and then escape with their lives. The surviving 300-400 Black residents of the town promptly fled, leaving almost everything behind.

According to "Dead Men Bring No Claims" by Melissa Fussell, afterward, the white residents of Ocoee distributed the former Black residents' property amongst themselves. "The victims were uncompensated for the most part, although some received a few dollars." Over 300 acres and 48 city lots were lost. In 2001, the land was worth an estimated $4.2 million.

A sham investigation into the election massacre

The NAACP sent Walter F. White to investigate, who conducted several interviews after arriving on November 5th. But White's report was one of few to accurately recount the atrocities that had occurred. Photos of the destruction were destroyed by the town of Ocoee and newspaper articles widely favored the white supremacists.

According to OPPAGA, although the United States Department of Justice sent Florida District Attorney Herbert S. Philips to investigate Perry's lynching and the election day violence, Phillips only looked into "whether or not federal election laws were violated." In his final report, Phillips stated that there was "no attempt to intimidate any Negroes in the casting of their ballots, and that there was no interference with the voting of qualified Negroes."

At a Hearing before the Committee on the Census in 1921, an Orange County grand jury also maintained that the Sheriff and his deputies "performed their full duty in maintaining law and order, and, after the brief outburst of passion over the killing of the two white men, admirably succeeded in the execution of their obligations as loyal American citizens."

However, the grand jury did exonerate Estelle and Caretha Perry, July's wife and daughter, who'd been charged with the deaths of the two white men who'd attacked their house. Unfortunately, the Perrys still lost their land, for their land had been sold off from under them "with the requirement" that the land never be sold to a Black person.

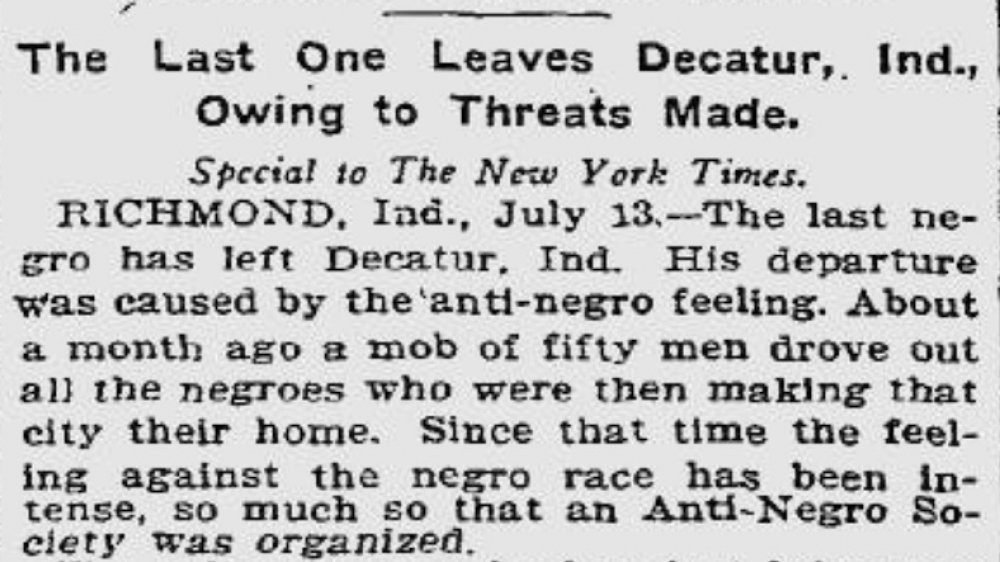

An all-white Ocoee emerges after the worst election day in history

After a few weeks, there were only two Black people left alive in the town, and by 1930 there were none. According to "Dead Men Bring No Claims," based on census records, "roughly 450 Black citizens disappeared from the town of Ocoee after 1920."

But unfortunately, Ocoee wasn't an isolated incident, following instead a pattern typical of sundown towns in the United States. And July Perry was one of 34 Black people who were lynched between 1877 and 1950 in Orange County. The state of Florida actually "led the nation per capita in lynchings" during this time period.

According to Gainsville.com, there were also lynchings of those who spoke out afterward about the massacre. In 1921, a lynch mob went after a man who was "talking a little too much" about the massacre. Although he was beaten and left for dead, he survived, perhaps to serve as a warning to others.

Ocoee remained all-white for over 50 years. According to The Weekly Challenger, "not a single African-American dared live in Ocoee for 60 years until 1981." According to Orlando Weekly, a Black person didn't vote anywhere in Orange County again until 1937.

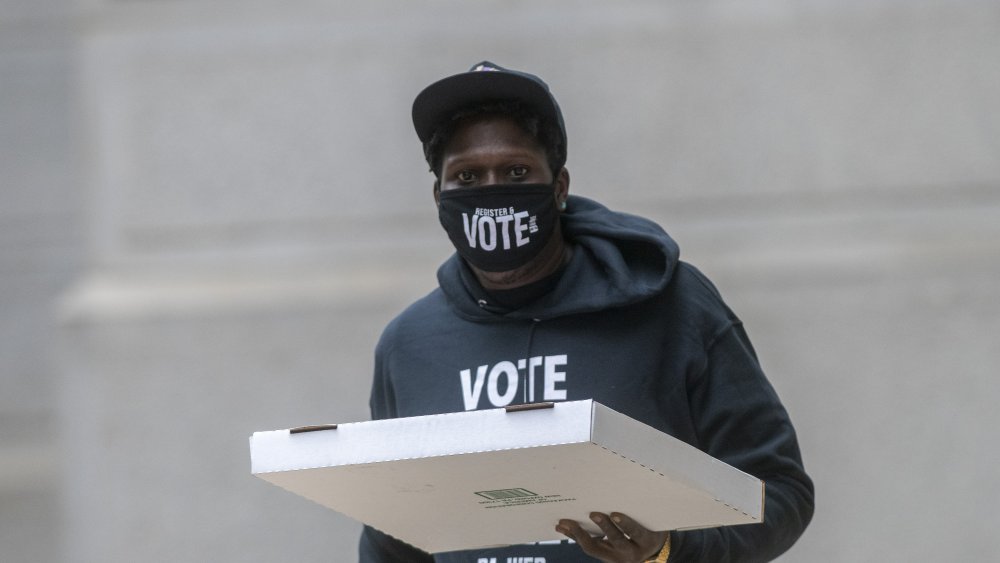

How much has changed this election?

Over the past forty years, the city of Ocoee has sought to change its reputation, and the story of Ocoee is slowly being taught. But according to Gainsville.com, it wasn't until 1996, when a research initiative called Democracy Forum set out to investigate and uncover the history of the massacre.

As of the 2020 passing of House Bill 1213, schools in Florida are now mandated to teach the massacre of 1920. There was also a failed attempt to provide reparations to those descended from victims of the massacre. The town has also shed its nature as a sundown town and as of the 2010 census, the population of Ocoee was "17% Black and 21% Latino."

Unfortunately, people of color, Black people especially, continue to suffer from voter suppression in 2020. In Texas, polling stations in communities of color were closed. In Florida, weeks before the 2020 election, Florida' secretary of state Laurel Lee decided to flag voters for removal from registration if they owed money from previous convictions — a monetary restriction not unlike their poll tax predecessors.

And despite approving a constitutional amendment that would allow people with felony convictions to vote in Florida, a ruling that largely affects Black communities, only about 45,000 people have registered to vote as a result of this. And it's unclear whether or not they'll be penalized for voting if they owe monetary fines.