The Crazy True Story Of The New England Vampire Panic

Before Robert Koch discovered the tubercular bacillus in 1882, the lack of understanding of the bacteria and the disease it caused, tuberculosis, led to some wild theories and attempts to curb the spread of the disease. Surprisingly, this intersected with vampire legends in an especially curious manner.

Throughout the 1800s, multiple towns throughout New England were gripped with a "vampire panic." Whenever someone in a family died from tuberculosis, their relatives often followed suit. And since people didn't know how the disease was spread, they decided that their dead relatives were sucking their life force from beyond the grave. They'd enact various rituals to rid the vampiric curse from their family, but more often than not tuberculosis would continue to wreak havoc.

Some who participated in the rituals didn't even really believe in vampires or the supernatural. They were simply desperate, at their wits end, and were "unwilling to leave untried any remedy that might save the lives of those they loved — even an outlandish or gruesome method" (via Mental Floss). However, the belief in vampires had been exported to the American colonies from Europe, and once the superstition was invited in, it was here to stay.

Unfortunately, even once the tubercular bacillus was discovered, it took some time for the knowledge to permeate through the American countryside. As a result, the last case of tubercular vampirism occurred in 1892, roughly ten years after Koch identified the cause of tuberculosis. This is the crazy true story of the New England vampire panic.

Colonial vampires

One of the earliest accounts of vampires in colonial America occurred in 1732. According to Boston 1775, two American periodicals picked up a story that was initially reported in March 1732 about a man named Arnold Paul who was tormented by vampires, becoming a vampire himself after his death. His body was found to be "too well preserved in the grave," and when his neighbors drove a stake through his heart, he's said to have let out "a horrid Groan."

While there was another European account that was reprinted in American periodicals in 1738, there were few home-grown American vampire stories. But as with the Arnold Paul story, there came little follow-up or discussion afterwards.

Although New England is known for its belief in the supernatural — with the Salem witch hunts as the most common citation — the vampire panic was substantially different from the witch hunts. While the witch hunts were politically motivated and sought to destabilize women's agency, especially that of women of color, the vampire panics stemmed from a fundamental misunderstanding of disease and causation.

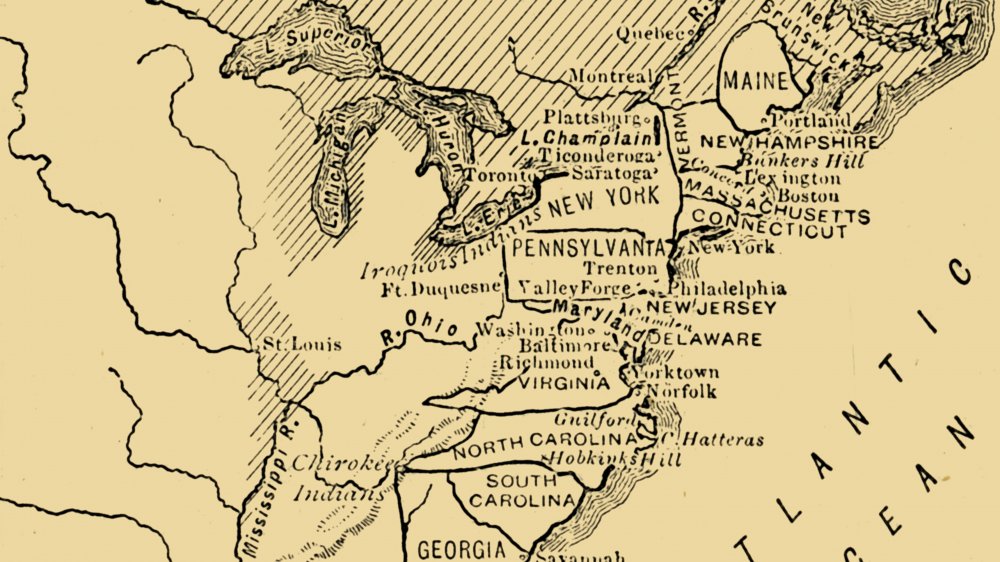

Some historians believe that the rituals used against vampires were brought to America by German doctors during the American Revolution. German vampires, or Nachzehrer, remained in their graves and affected people through "sympathetic magic." These rituals melded with Romanian traditions, which focused on the heart of the vampire and often recommended "cutting the heart out, burning it to ashes, and giving the ashes to the sick person or sick people."

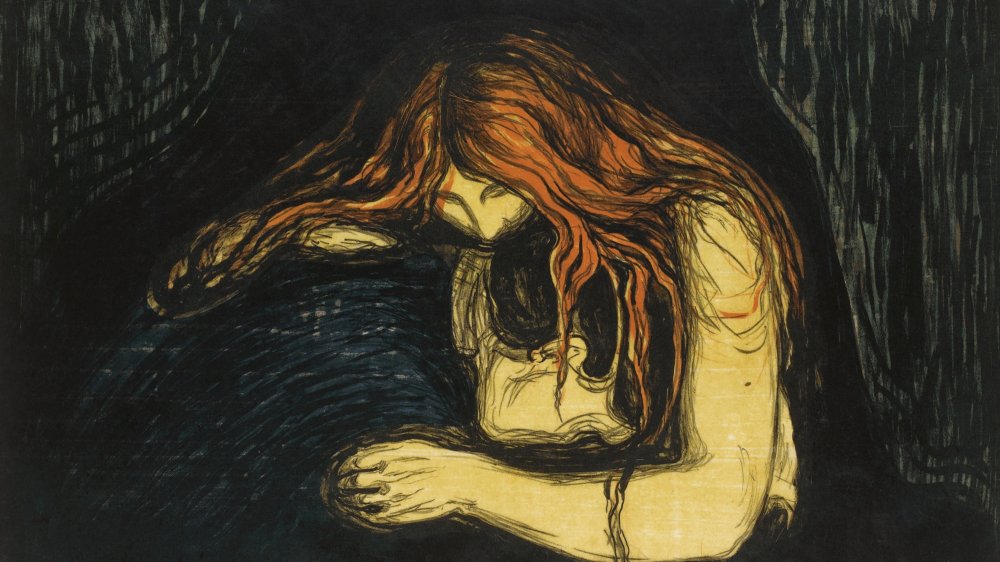

The consumptive nature of vampires

The belief that victims of tuberculosis became a vampire had to do with the physical manifestation of the disease and the fact that the spread of tuberculosis wasn't understood. According to How Stuff Works, the symptoms of tuberculosis often included sunken eyes and an ashen appearance. It was also a slow death, "almost as if the life was gradually being drained out of them," despite the person's will to live. This fit with the traditional dichotomy of vampiric legends that juxtaposed "wasting away" with a feeding desire.

According to The American Journal of Physical Anthropology, since tuberculosis gave the impression that its victims were being consumed — hence the name "consumption" when a deceased patient's family also became sick — it was believed that the deceased patient was feeding upon them from beyond the grave. However, ultimately the infection was simply spreading, since tuberculosis is especially transmittable in crowded quarters.

In the end, some villagers ended up believing that the first one to die from tuberculosis in a family was a type of vampire that would come out of its grave at night to secretly suck the life out of their families. According to Food for the Dead: On the Trail of New England's Vampires, by Michael E. Bell, as long as the dead body continued to naturally decompose, "either wholly or in part, the surviving members of the family must continue to furnish the sustenance on which the dead body fed."

How to kill the vampire

There were several ways to destroy the vampire, but the heart was consistently targeted, if not the entire body. According to The American Journal of Physical Anthropology, if fresh blood was found in the dead body upon exhuming it, then the heart was to be removed and burned.

The signs that the exhumed body was a vampire were thought to be a presence of blood in the heart, bloating, and the growth of hair and fingernails. But we now know that these are signs of normal decomposition. If the body was considered to be "far better preserved than expected," this was also a sign of vampirism.

The exact method of exhumation and destruction varied between communities. According to The Smithsonian Magazine, in Massachusetts and Maine, the bodies would simply be flipped face down into the grave. In Vermont, Rhode Island, and Connecticut, not only would the heart be burned, but people would inhale the smoke as a cure during the burning. This was slightly different from how vampires were dealt with in Europe, which comparatively favored beheaded corpses or binding their feet with thorns.

Often, the event would only be attended by neighbors and family. Other times doctors or clergymen joined in. Sometimes, the whole town might join in and turn the heart-burning event into a festivity that attracted hundreds of people.

Public festivals

Luckily, the accusation of "vampire" always came after a person was already dead, so no one ended up being tortured. And notably, those who sought to exhume and destroy the "vampires" weren't themselves calling the corpses vampires. The vampiric description came from journalists, historians, and outsiders. However, for all intents and purposes, the designation of "vampire" is fairly accurate for what the dead were accused of being.

While sometimes these rituals were shameful affairs done in the dead of night, other times they were public festivals. According to The Smithsonian Magazine, one such public festival occurred in 1830 in Woodstock, Vt., in the town green, where people gathered to watch a vampire's heart burn.

In 1793, Rachel Harris's "heart-burning ceremony" in Manchester, Vt. was such an exciting event that between 500 and 1,000 people attended the ritual. The lungs, liver, and heart were taken from the corpse, which had been buried three years prior, and burned "on the blacksmith's forge of Jacob Mead." According to The Psychology of Vampires, by David Cohen, "Timothy Mead officiated at the altar in the sacrifice to the Demon Vampire who it was believed was still sucking the blood of the then living wife of Captain Burton."

It's thought that Vermont had the most public heart-burnings, because Vermont's cemeteries were larger and often in the middle of the town, while Rhode Island's cemeteries were smaller and located around private farms. In Vermont, it would've been harder to do such a ritual secretly.

One of the first "vampires"

One of the earliest known cases of tubercular "vampirism" that's identifiable by name is the case of Rachel Harris. According to New England Today, Harris died of tuberculosis in 1790 in Manchester, Vt. Soon after her death, her stepsister Hulda married Capt. Isaac Burton, Harris' widower. But within months, Hulda was suffering from the same symptoms as Harris, and it was decided that Harris was responsible from beyond the grave.

The temperatures were reportedly frigid in February 1793, when hundreds of people flocked to watch Harris' organs removed and burned. Since it was so cold, the ground must've been frozen solid, which shows the dedication of those determined to dig Harris up.

While some versions of the story claim that some of Harris' organs were used to make a medicine for Hulda, it's unknown whether or not Hulda ended up being given the burned organs to consume. And unfortunately, according to A History of Vampires in New England, by Thomas D'Agostino, the ritual didn't work, and Hulda died from consumption on Sept. 6, 1793.

After Hulda died, the townsfolk decided that although Harris probably hadn't been a vampire, she had likely been a witch. Thankfully, Harris was already deceased, so she didn't have to suffer through the tests and trials that alleged witches had to go through.

Rhode Island becomes the vampire capital

Before long, Rhode Island became known as "The Vampire Capital of America" between 1870 and 1900. The isolated villages in South County were especially considered "a hotbed of vampire rumors between 1970 and 1900." And according to The Smithsonian Magazine, many of the exhumations also ended up occurring within 20 miles of Newport. Although the total number of vampiric exhumations isn't known, at least 80 "vampire killings" have been identified by author Michael E. Bell, although he estimates that's probably just "the tip of the iceberg."

According to The American Journal of Physical Anthropology, the people of Rhode Island were considered "uneducated and 'vicious'," despite the fact that some of the earliest incidents of "vampirism" occurred in Vermont.

And some of the legends persist to this day. The grave of alleged vampire Nelly L. Vaughn in Rhode Island Historical Cemetery No. 2, who died in 1889, is rumored to be cursed. On the bottom of the tombstone is an inscription that reads "I am waiting and watching for you," and a local university professor claims that lichen or vegetation refuse to grow on the grave for some unknown reason.

Vampiric legends in New England

Vampires had a long tradition in Europe, but by the time New Englanders started to panic about vampires in their midst in the 19th century, Europe had already been over their vampire panic for at least a century.

According to The Smithsonian Magazine, Germanic and Slavic immigrants brought the idea of vampires with them during the Palatine Germans' colonization of Pennsylvania or during the Revolutionary War. But the word vampire had been appearing around Europe since the 10th century, so it's likely that multiple sources brought the concept across the Atlantic.

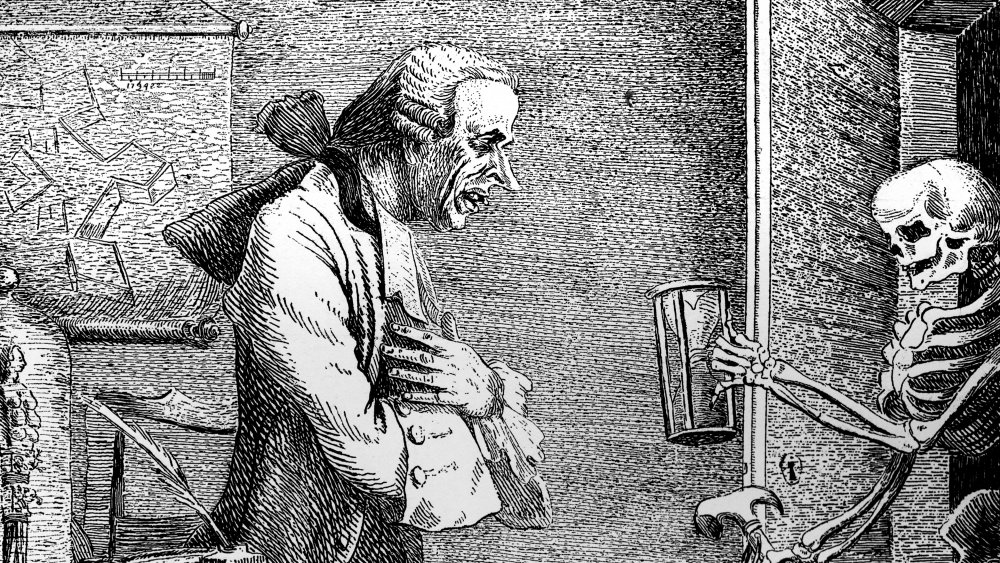

According to Boston 1775, one of the first known references to an American vampire panic comes from June 22, 1784. The Connecticut Courant printed an article that described a "Quack Doctor" who was convincing families to dig up and burn the bodies of their dead relatives in order to cure their consumption.

Having witnessed one of the exhumations himself, Moses Holmes wished to put an immediate end to the practice. "And that the bodies of the dead may rest quiet in their graves without such interruption, I think the public ought to be aware of being led away by such an imposture."

This wasn't even the first mention of vampires by the Connecticut Courant. Their first report about vampires came on Jan. 21, 1765, where they described the idea of evil blood-sucking spirits. "Such a notion will probably, be look'd upon as fabulous: but it is related and maintained by authors of great authority."

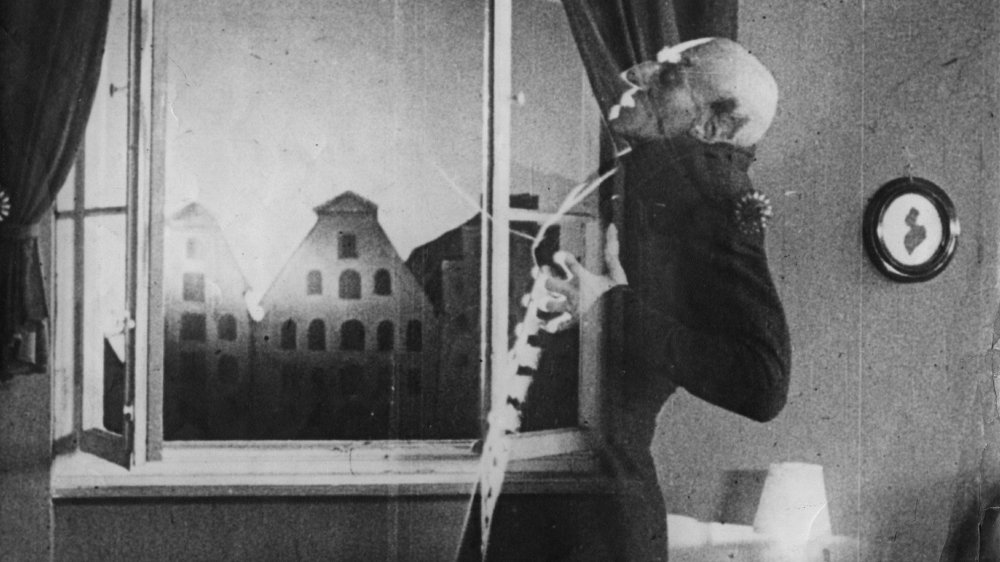

The case of Mercy Lena Brown

One of New England's last vampires was Mercy Lena Brown, whose exhumation ended up making the news. After watching her sister and her mother succumb to tuberculosis (via Medium), Brown died in January 1892 at the age of 19. By then her brother Edwin, whose health had been precarious, also seemed to be falling ill.

Neighbors approached George Brown, the father, and suggested the idea that the dead women were feasting on Edwin's "living tissue and blood." According to How Stuff Works, George agreed to let the bodies of his two daughters and wife be exhumed. But upon exhuming the bodies, the villagers were unsettled by the fact that Mercy's body was not as decomposed as the other two, despite the fact that she'd died more recently and in midwinter. The fact that her hair and fingernails had seemed to grow was also deemed suspicious, even though this is just an illusion from the flesh retracting.

The liver and heart were both removed from Mercy's body, burned to ashes, and given to Edwin to drink. Unfortunately, the ritual had little discernible effect, and Edwin died soon after.

According to The Smithsonian Magazine, many claim that Bram Stoker's Dracula was directly inspired by this event. And considering that newspaper accounts of Mercy's exhumation were found in Stoker's files after he died, it's more than likely that Stoker was influenced by the events in his day.

An anthropologist offers his take on vampires

After Mercy Brown was exhumed, and local papers wrote about the event, an anthropologist named George Stetson went to Rhode Island to uncover the "barbaric superstition," later publishing his account in The American Anthropologist in 1896.

In Rhode Island, Stetson identified vampiric hotbeds in East Greenwich, Kingstown, Foster, and Exeter, and notes that "it is believed that consumption is not a physical but a spiritual disease, obsession, or visitation." It's noteworthy that during this time, many of these towns, such as Exeter, had dozens of vacant farms as a result of westward expansion. And with areas isolated and sparsely populated, it was easy for superstitions to take root.

According to Mental Floss, Stetson connected the vampiric beliefs in New England to rituals that had been done in the Caribbean, ancient Greece, and parts of Europe. Stetson describes one man in Rhode Island who enacted the heart-burning ritual and believed himself to have been cured as a result. Although "when questioned as to his understanding of the miraculous influence, he could suggest nothing and did not recognize the superstition even by name."

One of the reasons that the Brown case attracted so much attention is because Robert Koch had identified the tuberculosis bacterium in 1882, ten years before Brown's exhumation. But according to The Smithsonian Magazine, knowledge of this discovery didn't make its way into rural villages for decades, and drug treatments wouldn't become widely available until the 1940s.

Farmer JB-55

In 1990, a cemetery was found in Griswold, Conn., that yielded a rather curious find. While many of the burials looked like fairly standard burials from the 18th and 19th centuries, one plot was particularly spooky.

According to The Smithsonian Magazine, not only were tacks placed on the coffin, spelling out "JB 55," but the bones were also in a curious arrangement. The head had been cut off the body and put on the chest, which was itself broken open. Femurs were also placed under the skull to create a "skull and crossbones" impression.

It's estimated that JB 55 had been buried for roughly five years when he was exhumed. It's believed that when it was discovered that his heart had completely decomposed, an alternative ritual was thought up to rid the vampiric nature from the body.

In 2019, JB 55 was identified through genetic markers with the last name Barber. Based on an 1826 newspaper notice that recorded the death of Nathan Barber, it's believed that JB 55 was John Barber, Nathan's father, whose coffin was buried nearby with the initials NB 13. This means that the elder Barber likely died in 1821 at the age of 55, and despite attempting the vampiric ritual on his father's dead body, his son still succumbed to the same fate that had claimed his father.