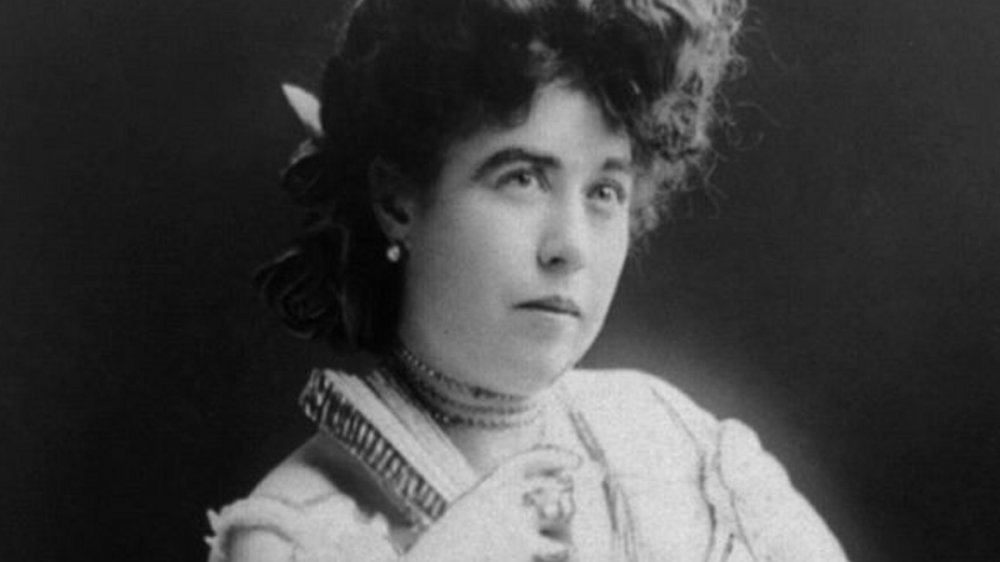

The Untold Truth Of The Unsinkable Molly Brown

Ever cheerful, ever helpful, ever hopeful, Margaret Tobin Brown remains a heroine in both Colorado and even America today. Born into a working class family before becoming obscenely wealthy, Margaret became one of the most philanthropic socialites of her time. Today, she is best known as the stalwart survivor of the Titanic who not only encouraged those in her lifeboat as the ship sank, but rewarded the brave who helped others in the aftermath—and then went on to perform many other amazing acts of kindness.

As an American folk hero, Margaret Brown has indeed become larger than life. These days there are several myths about the woman, which certain historians and writers have eagerly fed readers to make Margaret seem even more flamboyant and enigmatic than she really was. During her lifetime for instance, she was never, ever known as "The Unsinkable Molly Brown," confirms the Molly Brown House Museum in Denver. That moniker was assigned to her by writers Gene Fowler, Caroline Bancroft, and others whose whimsical and sometimes fictional stories about the lady bloomed into accepted facts over time. But even their portrayals of Margaret Brown really couldn't surpass the truth about the woman, whose life was far more interesting and noteworthy than any of the fibs told about her. Read on for the untold truth about the enigmatic and charming "Molly Brown."

Margaret Brown and her humble beginnings

Margaret Brown was born in July 1867 in a tiny, three-room cottage in Hannibal, Missouri (pictured). Her parents John and Johanna Tobin already had three other children and notably, the 1870 census lists Margaret as Maggie, not "Molly." Historic Missourians verifies Margaret and her siblings attended a private school where their aunt was a teacher, through the 8th grade. Some have claimed that young Maggie played with writer Mark Twain as a child and even once rescued him from drowning. But that would have been a neat trick, seeing as Twain was already 32-years-old when Margaret was born.

It is true that Margaret left school at age 13 and went to work at the Garth Tobacco Factory in Hannibal to supplement the family income. But after her half-sister Mary Ann moved to Leadville, Colorado in 1883, followed by her brother Daniel, Margaret too yearned to move West. She got her wish in 1886, when Daniel summoned her to Leadville. Margaret would be mortified if she knew that the film The Unsinkable Molly Brown portrayed her as a saloon girl in Leadville. In reality, she eventually went to work sewing draperies and other items for Daniels, Fisher & Smith dry goods store. She was presumably still there when she met the man of her dreams, John Joseph "J.J." Brown.

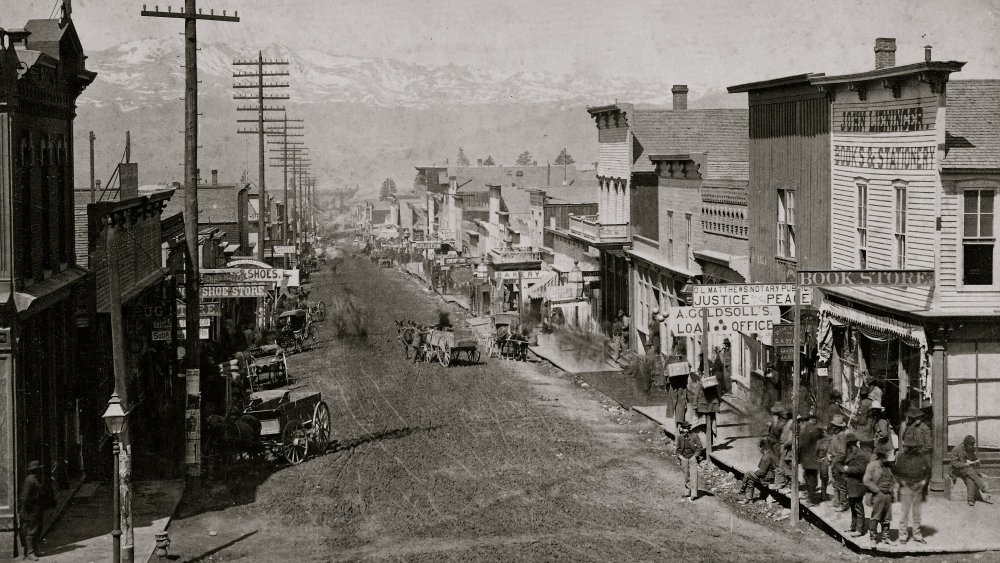

Margaret marries J.J. Brown

Leadville was a real eye-opener for young Margaret. Here miners toiled to find silver and gold in a typical, rough-and-tumble boomtown. Margaret remained resilient, joining the Catholic Annunciation Church and volunteering for the local soup kitchen and other charities. She soon met J.J. Brown, a fellow Irish descendant, at a church picnic. J.J. was gainfully employed as a mining engineer (not, as one of the myths claims, as a prospector) at the Ibex Mining Company. To Margaret, he seemed a suitable enough prospect for marriage. One tale, from Margaret's own descendants, claims J.J. Brown showed up for their first date in a worn, single-horse carriage and that the lady declined to go out with him. The next evening, however, J.J. returned in "an elegant two-horse affair" that Margaret found more acceptable.

Either way everyone in Leadville, according to Margaret's friend Thomas Cahill, "thought it was a wonderful match." Following a summer courtship, Margaret and J.J. were married in September 1886 at the Annunciation Church. J.J. Brown was 31-years-old; Margaret was just 19. But the marriage seemed set in stone when the newlyweds set up housekeeping in J.J.'s little two-room cabin at Stumpftown, a mining community near Leadville.

Margaret and J.J. Brown's children

Even before her marriage to J.J. Brown, Margaret got the gist of life as a mining man's wife. "I loved Jim, but he was poor," she would later say according to biographer Kristen Iversen. "Finally I decided that I'd be better off with a poor man whom I loved than with a wealthy one whose money had attracted me." The couple would indeed both remember that their early years together were most happy, and Margaret was able to take lessons in literature and music. She also was able to return to Hannibal for the birth of her first child, Lawrence "Larry" Palmer Brown in 1887, and upon her return to Leadville the Browns bought a house in town.

By the time a second child, Catherine "Helen" Ellen Brown, was born in 1889 several of Margaret's family members had moved to Leadville. The Browns purchased an even nicer house as Margaret worked to help establish the Colorado Chapter of the National American Woman's Suffrage Association, according to Encyclopedia Titanica. She also continued working at the soup kitchen and assisting other mining families to improve the schools of Leadville. J.J., meanwhile, continued working his way up at the mining company, according to Biography. But he also disapproved somewhat of Margaret's progressive work to help miners and their families, even as he himself struggled to make sure those same miners were able to keep their jobs.

Margaret and J.J. Brown strike it rich

In 1893, an event took place that would affect silver miners and millionaires across the west. The Silver Purchase Act of 1890, which had made silver the most valuable mineral in America, was repealed in 1893. Like other silver mining towns, Leadville plunged downward quickly as unemployment skyrocketed to 90 percent. Undaunted, J.J. Brown figured out a way to access valuable gold ore laying in the bottom of the Ibex's Little Johnny Mine. By December, according to the Colorado Daily Chieftain, the Little Johnny was producing 150 tons of ore per day at $25 in gold per ton, or $3,750 to be precise.

As it happened, according to the Molly Brown House Museum, J.J. Brown was already a part owner of the Ibex Mining Company, and the success of the Little Johnny was attributed directly to him—especially when the mine yielded "the largest vein of gold ever discovered in North America" to date. J.J.'s buddies at the Ibex accordingly awarded him 12,500 shares of stock, as well as a seat on the board of directors. We can thank historian Caroline Bancroft for the story of Margaret accidentally burning the Brown's fortune in the woodstove of the family home. That didn't happen. Margaret did say she kept coins in the stove—but never burned them either by accident or on purpose.

The Browns move to Denver

Within a year of striking it rich, Margaret and J.J. Brown relocated to Denver (pictured). They purchased an elegant home at 1340 Pennsylvania Avenue from Isaac and Mary Large who, ironically, lost their fortune in the silver purchase crash. The cost was $30,000, nearly a million dollars today. But Margaret could not help but notice others who were affected by the silver crash, and the poverty in the slums around the downtown area. By 1895 she was involved in founding the Denver Woman's Club, which was part of a national network working to improve lives for women and children.

As Margaret pursued her causes, J.J. continued purchasing land in southwest Denver. In 1895, he began construction on the Avoca Lodge, an estate spanning over 400 acres that served as the Brown's summer home upon its completion in 1897. The Avoca not only provided a respite for the family, but also was the scene of lavish parties where guests danced the night away on an oak dance floor. Margaret balanced her time entertaining by looking after her mother and others who lived with the Browns by the time of the 1900 census. Also in 1900, she furthered her education by attending New York's Carnegie Institute for a year to learn an amazing five languages (French, German, Italian, Russian and Spanish), as well as literature and drama.

Margaret Brown versus Louise Hill

According to Women of Consequence, the Browns made the newspapers often with reporters noting where they went, what they wore, who they spent time with and the parties they threw. Margaret's contributions to building the Cathedral of Immaculate Conception for St. Joseph's Hospital, her support in constructing more playgrounds to keep children out of trouble and her founding of the Denver Dumb Friends League, according to the Molly Brown House Museum, did not go unnoticed. The museum does, however, maintain that because the Browns were "new money," they were not always invited to functions with other wealthy Denver citizens—yet they were never outright "snubbed." But is that really true?

Most stories of Margaret being snubbed by Denver society are attributed in part to Caroline Bancroft, who called our heroine "such a fraud. She lied about everything." At the bottom of Bancroft's claim to Margaret being ostracized is Louise Hill whose husband, Crawford, was quite wealthy. Louise, whom the Denver Post maintains "could make or break anyone with social aspirations" held court with her own club dubbed the "Sacred 36." The roster included some of the wealthiest wives in Denver—but excluded Margaret Brown due to her "unrefined behavior, Catholicism, and new money status" according to History Colorado. In turn, Margaret called Louise "the snobbiest woman in Denver." Not until years later would Louise Hill be forced to reckon with Margaret Brown.

Maggie Brown's marriage turns sour

Undaunted by Louise Hill or anyone else, Margaret Brown continued her philanthropic efforts. In 1901, she dared to run for a seat in the state senate—an outright shocking move even in the budding Edwardian era. J.J. seems to have been especially unnerved by the whole thing, according to the Molly Brown House Museum, which might be why Margaret withdrew from the race. The couple next embarked on an expansive trip around the world, visiting France, India, Ireland, Japan, Russia, and many places in between. The trip refreshed the Brown's marriage to a great extent, and Margaret even wrote some articles detailing India's caste system, which were published in Denver's newspapers. Then in 1903, Mary Ann Tobin, the wife of Margaret's brother Daniel, died in Pueblo according to Leadville's Herald Democrat. Margaret willingly took in Mary Ann and Daniel's three daughters, raising them as her own.

Family love aside, something was still not right in the Brown house. In 1906, J.J. sold the Avoca Lodge (pictured). He also continued balking at Margaret's outspoken efforts, to the extent that the couple quietly separated in 1909, according to Biography. The agreement was quite amicable, says Britannica, with Margaret retaining ownership of the Brown's Denver property and receiving a trust fund of $25,000 with $700 in monthly distributions. It was enough for Margaret to continue her work, and she did—even running for Congress several times between 1909 and 1914.

Margaret Brown's night on the Titanic

History buffs are plenty familiar with the Titanic, the "unsinkable" ship that collided with an iceberg on the night of April 14, 1912 and indeed sank just hours later. Margaret was aboard that ship, having boarded in France. Daughter Catherine was supposed to board in England, but missed the boat. Margaret remembered that as she and others were put on Lifeboat #6 her friends, Colonel John Jacob Astor and his wife, also tried to board. The three seamen in the lifeboat, however, ordered the Colonel off of the boat despite his wife's delicate health. He later drowned in the icy waters.

Others in the water concerned Margaret greatly, according to writer Stephanie L. Barczewski. She and other women implored Quartermaster Robert Hitchens to help save them, but he refused. He also spurned their pleas to let them row to keep warm. Margaret ultimately made her way to the stern and took the tiller from Hitchens, threatening to throw him overboard if he interfered. She did not, verifies the Molly Brown House Museum, strip down to her corset and wave a gun around as seen in the movie. She did, however, complain quite loudly to newspapers about the men's refusal to help once she was aboard the RMS Carpathia. And the next morning, Margaret and other women set about assisting other survivors with clothing and other necessities.

'The Unsinkable Mrs. Brown'

Margaret and her friends had raised $10,000 for the Titanic survivors by the time the Carpathia sailed into New York Harbor, says New World Encyclopedia. According to Findagrave, Margaret told reporters she survived the Titanic due to "typical Brown luck. We're unsinkable." Whether or not she really said it, Denver gossip columnist Polly Pry referred to Margaret as "the unsinkable Mrs. Brown" per the Molly Brown House Museum. Margaret, meanwhile, furthered her fundraising to award the Carpathia's Captain Rostron and his crew. Margaret herself presented a loving cup to Rostron on behalf of her fellow survivors. She also, according to the Titanic Historical Society, gave some 300 medals to the crew and officers of the Carpathia—including 14 which were solid gold.

As word of her heroic efforts and kindnesses spread, Margaret Brown indeed became a heroine to Americans. Yes, that part is absolutely true. Margaret took her new fame in stride. "After being brined, salted, and pickled in mid ocean I am now high and dry," she cheerfully wrote to Catherine according to History. "I have had flowers, letters, telegrams—people until I am befuddled. They are petitioning Congress to give me a medal... If I must call a specialist to examine my head it is due to the title of Heroine of the Titanic." Margaret never received a Congressional medal, but she did win something very important to her: a special invitation to a luncheon thrown just for her by none other than Louise Hill.

Margaret Brown's heroism didn't stop after the Titanic

Margaret used her hard-earned power wisely. In 1914, after striking coal miners at the company-owned town of Ludlow (pictured) were violently attacked resulting in the deaths of eight men, but also 11 women and children, the ladies of the camp appealed to Margaret for help. The woman once again jumped into action, raising money to send "nurses, shoes, and clothing to Ludlow." She also successfully talked John D. Rockefeller into coming to Colorado and settling the strike.

Margaret eventually began spending more time at her summer home in Rhode Island. It was there that she continued her work with women's suffrage campaigns, giving a speech at the 1914 Conference of Great Women. She also campaigned for the seat of Colorado senator once again, but withdrew from the race upon the advice of her constituents. With the onset of World War I, Margaret turned her attention to working with the American Committee for Devastated France instead.

Then J.J. Brown died in 1922. "I've never met a finer, bigger, more worthwhile man than J.J. Brown," Margaret said. And although Encyclopedia Titanica and other websites claim J.J. neglected to leave a will which pitted Margaret against her own children for the inheritance, J.J. did actually file a will naming Margaret as executrix of his estate. Another rumor, squelched.

Margaret Brown turns to acting

Following J.J.'s death, Margaret continued traveling. According to Historic Missourians, she was staying at a hotel in Florida when it caught fire, and led her fellow guests down the fire escape to safety. It's hard to say whether that story is true, but it is a fact that late in her life Margaret pursued another of her lifelong interests: acting. Biography says she performed in a play entitled L'Aiglon in both Paris and New York. The play was written by Edmond Rostand in 1900, with actress Sarah Bernhardt creating the title role. Margaret "emulated" Bernhardt in a reprise production of the play.

Her acting accolades aside, Margaret received one more honor. In 1932, she was presented with the French Legion of Honor, not only for her assistance to survivors of the Titanic, but also her work during World War I. A happy Margaret Brown retired her room at New York's Barbizon Hotel—which also was home to other aspiring actors—on the night of October 25. She did not wake up, dying in her sleep as she hopefully dreamt of her many achievements in the past and of those to come. Biography says the cause of death was an undetected brain tumor. She is buried near J.J. in New York's Cemetery of the Holy Rood.

Memories of Margaret remain

Would the Unsinkable Mrs. Brown be happy that in death she was even larger than in life? Possibly, for accolades for the woman are many. No less than 10 biographies have been written about Margaret, and in 1960, producers Lawrence Langner, Armina Marshall, and Dore Schary presented the play, The Unsinkable Molly Brown, at New York's Winter Garden Theater. The original production starred actress Tammy Grimes, and the play continues on the playbills of theaters across America today. Then there is the 1964 film version of the same title, which starred Debbie Reynolds and largely fed off of the myths about Margaret and scored three Oscars out of six nominations.

Those desiring a more realistic look at the life of Margaret Brown can visit Molly Brown Birthplace Museum in Hannibal, Missouri, which remains furnished as it would have been during Margaret's time and tells the story of her early life. In Denver, the Brown's palatial home on Pennsylvania Street was rescued from demolition in 1970 and made into the Molly Brown House Museum (pictured). According to the website, the museum receives some 45,000 visitors a year and remains "committed to enhancing the city's unique identity" by telling of Margaret's prolific effect in American politics and philanthropy. Both museums are an incredible tribute to Margaret, who was inducted into the Colorado Women's Hall of Fame in 1985.