The Dramatic Way American Presidents Age During Their Presidency

We've all heard the talk and seen the photographic evidence: being President of the United States is a tough job. The stress is almost mind-boggling, and it's tough to imagine if you're not in politics, so let's put it this way. Imagine knowing you have one kid that you'd got to pick up from school, but you've also got to work late, cook something for tomorrow's potluck lunch, mediate a dispute between your neighbors, figure out which bills you're going to pay, talk to the town about fixing the potholes in the roads that gave you yet another flat tire, get in an exercise session, and then visit your cousin in the hospital.

Now, imagine doing that for 330 million people, and that's kind of what it's like to be president.

It's no secret that presidents tend to change a lot in the years between their election and their exit of the White House. Most have more than a few gray hairs, faces are lined, and the stress is clear. Even Stephen King made mention of the phenomenon in The Stand, writing: "We used to watch presidents decay before our very eyes from month to month and even week to week on national TV..." What's going on here? Is it such a dangerous job that it takes a massive physical toll? Let's look at the surprisingly complicated answer, and see just how different some presidents look before and after they held the office.

Let's talk about how old presidents have been... historically speaking

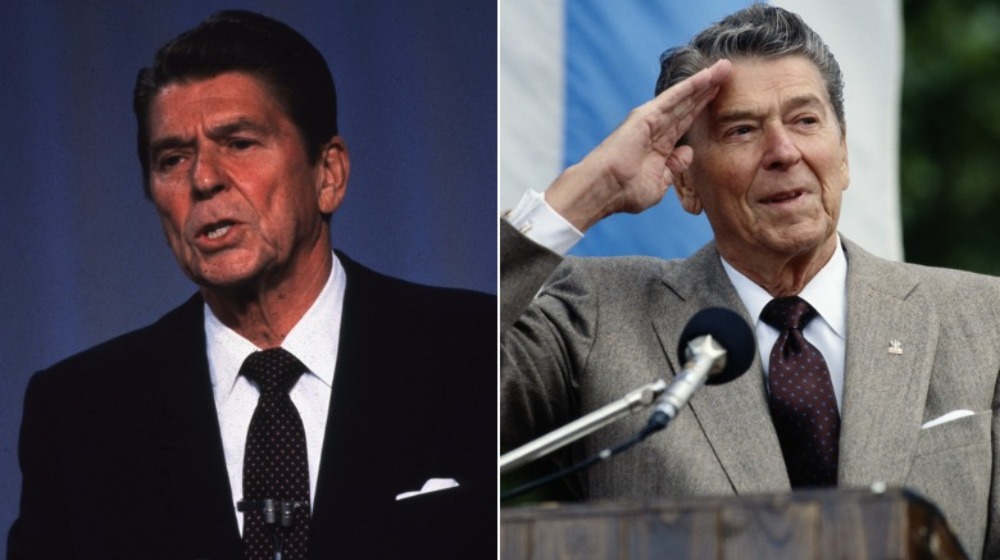

In 2020, the presidential election was filled with talk of age. Sitting president Donald Trump and challenger Joe Biden were among the oldest contenders for the position and in fact, Trump was — at the time — the oldest president the country had ever had. The official POTUS site lists his age at inauguration as 70 years, 220 days — almost a year older than his closest contender, Ronald Reagan.

While there have been a handful of 60+ presidents in recent memory, here's the surprising thing: most have been in their 50s when they took office, and that includes presidents like Abraham Lincoln (52), Franklin D. Roosevelt (51), George Washington (57), and Thomas Jefferson (57).

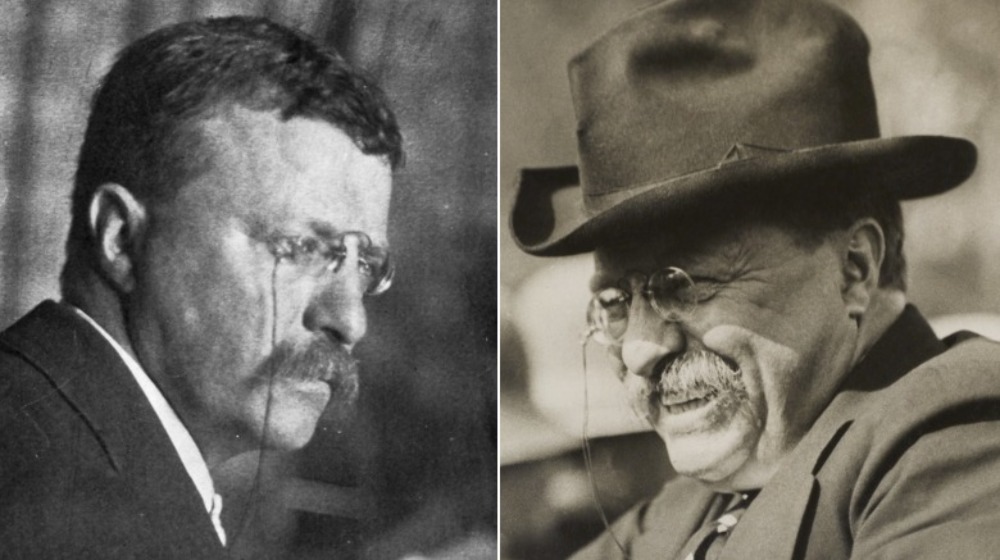

Nine presidents were in their 40s, and the youngest isn't who you might think it was. While JFK has held onto his reputation as a young president, Theodore Roosevelt (pictured) was actually about a year younger when he was inaugurated. He was just 42-years (and 322 days) old, but he'd held office since (via USA Today) he was elected to the post of New York Assemblyman at just 23-years-old. He became a vice presidential nominee at 41, and when William McKinley was assassinated and Roosevelt took over, he was surprisingly young. And yes — he was reelected.

Here's the rule of presidential aging, according to the Cleveland Clinic

In 2009, Dr. Michael Roizen of the Cleveland Clinic talked to CNN about the health — and potential aging — that then-President Barack Obama was likely to confront. President Obama was 47-years-old at the time, and while Roizen noted he was "...a fairly young guy and doesn't have great of a risk," he went on to say that "If he's president for eight years, he ends up having the risk of disability or dying, like someone who is 16 years older."

What does that mean? According to Roizen, "The typical person who lives one year ages one year. The typical president ages two years for every year they are in office." Roizen says that he came to that conclusion by collecting and analyzing the public medical records of presidents going back to Theodore Roosevelt. He looked at things like blood pressure and factors like lifestyle choices and levels of exercise, and found plenty of evidence in the physical changes of recent presidents like Ronald Reagan (pictured). Reagan, he says, went from "joking and incredibly quick-witted about current events" to making "jokes... of olden days." Even Bill Clinton — who made it a point to emphasize his youth — left office with white hair and a heavily wrinkled face, after being worn down by the stress and scandals.

That seems logical, based on the way we see presidents change. But other studies suggest there's much more going on here.

The rule of presidential aging might not be true at all

S. Jay Olshansky is a professor at the University of Chicago's School of Public Health and a human longevity expert. He decided to take a closer look at whether or not presidents actually did age faster while in office, and he found (via History) that it's not straightforward at all. Removing the presidents who were assassinated in office — Lincoln, Garfield, McKinley, and Kennedy — Olshansky laid out a table of inaugurations, life expectancy, and estimated life expectancies for the presidents still living. The results were pretty shocking.

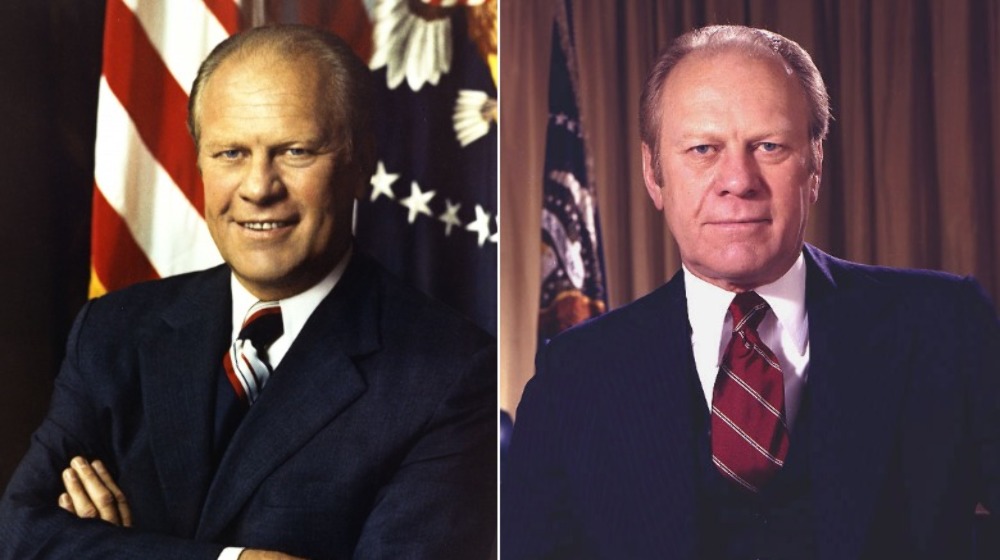

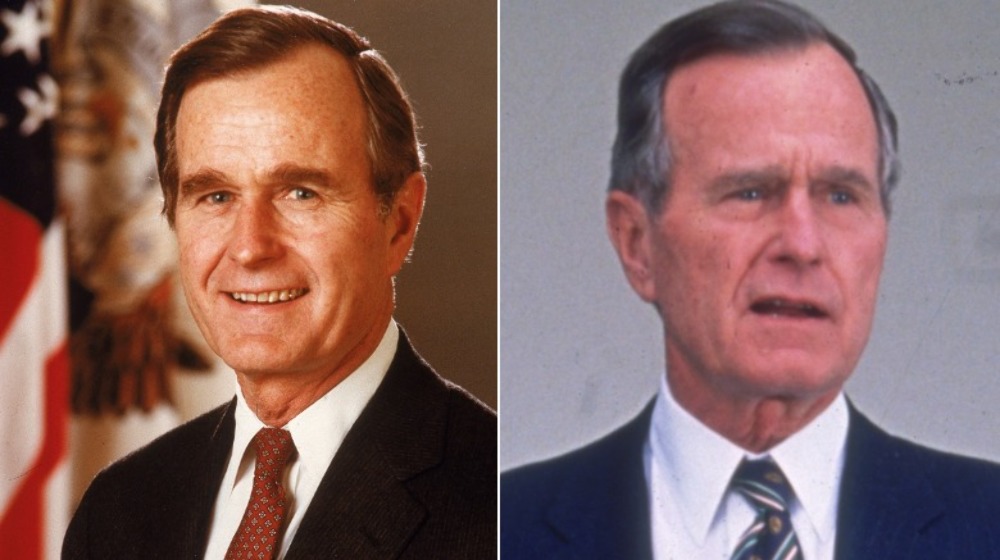

Looking at just the first eight presidents, he found their average life span was 79.8 years. That's significant, especially considering their average everyday contemporary man had a very good chance of dying before they hit 40. Fast forward, and the trend holds. Of the 34 presidents who have died of natural causes, 23 lived longer than the life expectancy of their time. Some did it by a lot: John Adams and Herbert Hoover both died at 90, and Gerald Ford (pictured, before and after three years in office) and Ronald Reagan were both 93 (via Harvard Health).

While there were some presidents that died young of natural causes — James Polk was 53, while Chester A. Arthur and Warren G. Harding were both 57 — Olshansky found that in spite of showing signs of premature aging, former presidents had a good chance at beating the odds to live a very long life post-office.

So, what's going on here?

Premature aging and a longer-than-normal lifespan seem to be at complete odds with each other, so what's going on here? Olshansky has a few things that might explain it, and it starts with the average age most presidents have been when they enter office. "If you take any 50-year-old man or 40-year-old man and you follow them for four years or eight years, chances are they're going to be losing the hair that they have and in many instances, a significant portion of it will turn gray," he says (via History). "So what we're seeing [...] is really not inconsistent with what we see in any other man [that] age in the US or elsewhere."

And that kind of makes sense. Eight years is a long time, and Olshansky adds that they're also in the public eye day in and day out. They're high-profile, so when they complain about things like back pain it's front-page news even though it happens to literally everyone in the world. He reminds us: "[...] the rest of us experience [these issues] when we grow older as well."

He also says (via the Journal of the American Medical Association) that not only did early presidents have a good chance at living a long life because they'd already survived their most dangerous years, but that presidents also have something important in common: wealth, status, and access to the very best medical care available, no matter what the era.

Are we seeing actual aging?

Olshansky's study of presidential aging, published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, does mention the outward changes many have noticed happening in presidents over the years. He says that they're all normal effects of the human aging process, and it's not known whether or not being elected as president means you're guaranteed to appear to age faster than if you hadn't been.

Experts have tried to figure out what's going on. Ronan Factora, a Cleveland Clinic physician who specializes in geriatric medicine, suggests (via The Denver Post) that what people are seeing are the consequences of long-term, chronic stress. Changes are gradual, he notes, and one stressful event isn't going to make much difference in someone's appearance. Four or eight years of never-ending stress is another story.

That's because a body under stress has constantly high levels of hormones like adrenaline and cortisol. When those hormones are present in high quantities for a long time, they put pressure on the circulatory system, and can ultimately cause things like a loss in bone mass, insomnia, and a weakened immune system.

Does that translate to gray hair and wrinkly faces? Psychology Today says the science is, well, also gray. While there's some scientific evidence that suggests stress directly impacts the way we look — mostly by prematurely wearing down the body's systems — researchers haven't been able to work out exactly how everything is related.

A hidden danger of being president

Some have suggested that along with signs of premature aging come a hidden danger: heart disease.

In 2019, Bernie Sanders made headlines when — after suffering from what the American Heart Association described as "chest discomfort" — he was taken to the hospital, found to have a blocked artery, and underwent surgery to have several stents implanted. That prompted New York Magazine to take a look at presidents and their history of heart disease. In short? They found a lot. Dwight D. Eisenhower (pictured) had a major heart attack while in office, along with a stroke. LBJ had a heart attack at 47 and several more after he left the presidency — the final one was fatal. Warren G. Harding had his fatal heart attack while in office, and others — like George W. Bush and Bill Clinton — had heart surgeries not long after leaving office. The American College of Cardiology lists even more: Grover Cleveland suffered a fatal heart attack, Calvin Coolidge died of a blood clot in his heart, while William Taft, FDR, Harry Truman, and Gerald Ford were also diagnosed with various types of heart disease.

While not a president, it's worth noting that Dick Cheney had his first heart attack when he was just 37-years-old, and in 2012, he had a heart transplant — all of which suggests there's a greater danger than a few gray hairs lurking in the White House.

The stress of the presidency might trigger latent issues

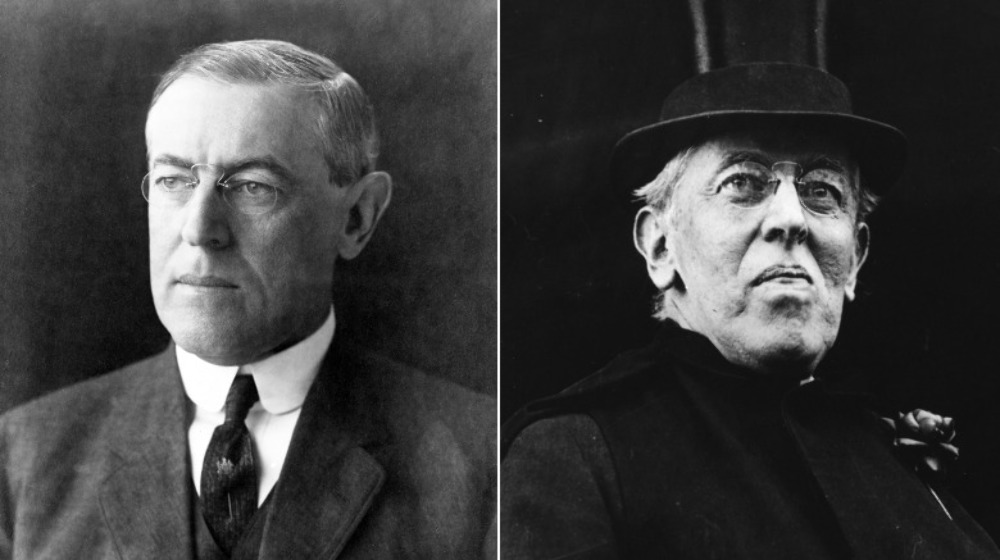

Physical health is just one aspect of any person — mental health is of the utmost importance, too. So, what impact does the presidency have on that? According to the BBC, one 2006 study suggested that as many as 49 percent of presidents suffered "a malady of the mind" at some point during their lifetimes. (It's also worth noting that's in line with a broader national average.) Around 27 percent of presidents were struggling with mental health while in office, including James Madison and Woodrow Wilson (pictured). Both of those presidents met the diagnostic criteria for depression.

Part of being a president means being in the public eye, which makes it both surprising and understandable that some — including Ulysses S. Grant and Thomas Jefferson — struggled with social anxiety. And others — namely John Adams and Theodore Roosevelt — met the criteria for being diagnosed with bipolar disorder.

And yes, experts say that the development of mental health issues can be directly related to the stress of the presidency. According to Jonathan Davidson, the head of the study: "The pressures of such a job can trigger issues in someone that have been latent. Being president is extremely stressful, and nobody has unlimited capacity to take it forever and ever."

Presidents struggle with personal and professional difficulties

In 2015, then-Vice President Joe Biden announced the tragic passing of his son, Beau. Diagnosed with brain cancer two years before, he passed after first being given a clean bill of health, then suffering a relapse. Then-President Obama issued this statement (in part, via The Guardian): "Michelle and I are grieving. Beau Biden was a friend of ours. His beloved family... are friends of ours. And Joe and Jill Biden are as good as friends get."

It's easy to forget that personal lives don't stop when someone steps into the office of president, and in some cases, personal tragedy has compounded the stress of the office. Take Franklin Pierce. According to the BBC, Pierce's 11-year-old son — his only surviving child — was killed in a train derailment just before his inauguration. The loss was devastating: Pierce ultimately spiraled into grief, sought solace in alcohol, and died of liver failure.

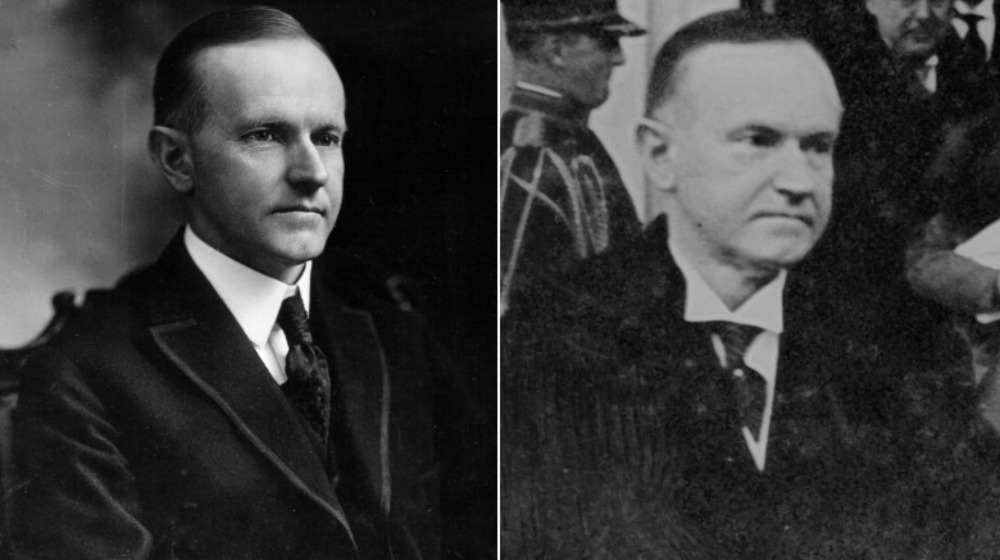

Calvin Coolidge (pictured) was in the White House when his 16-year-old son died after a foot infection — caused when he played tennis on the White House courts, without socks — turned into deadly blood poisoning. Coolidge once remarked that, "Whenever I look out of the window, I always see my boy playing tennis on that court there." His behavior grew more and more erratic, and he all but retreated from public life. He later wrote: "I do not know why such a price was exacted for occupying the White House."

Many presidents have been smokers

Lifestyle choices have a lot to do with who quickly someone might develop signs of aging, and according to Mother Jones, many US presidents have had one particular lifestyle choice in common: they're smokers. Who are we talking about here? During Obama's presidency, his former cigarette use was a huge deal — Time says that a photo from a G-7 conference where he appeared to be holding something that was possibly a pack of cigarettes sent the nation into an outright tizzy. The Obamas — and the White House physician — said he was tobacco-free, but that wasn't the case for other presidents.

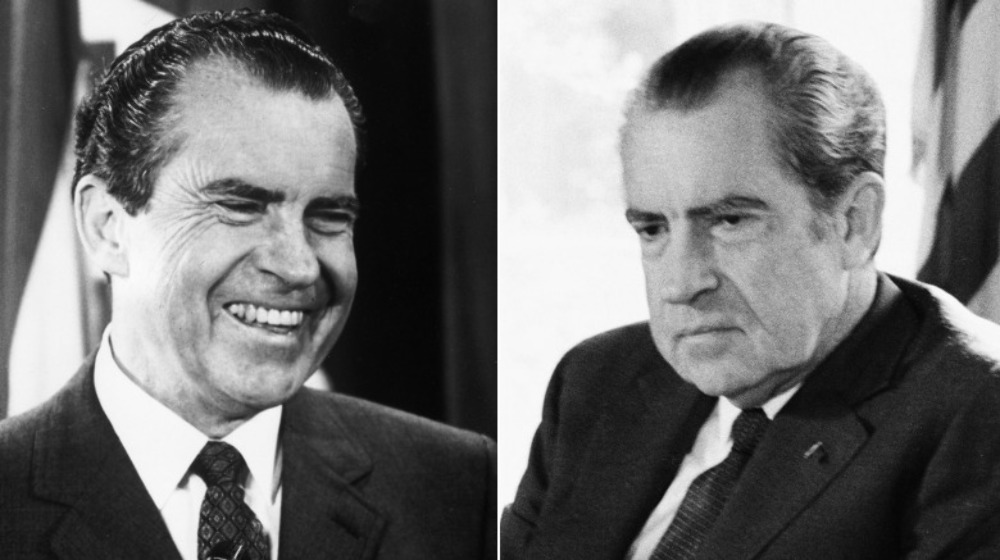

According to the San Diego Reader, smokers included Eisenhower and LBJ, with Nixon's (pictured) habit up in the air — some sources suggest he'd quit by the time he was president, while others describe him as a "champion cigar smoker." JFK opted for pipes and cigars, some of FDR's most famous photos show him with a cigarette, and they add that as far as modern presidents go, Truman, Carter, Clinton, and the Bushes were the non-smokers.

And yes, that could absolutely have something to do with their in-office aging. According to a lecture given at the Symposium on Pathophysiology of Ageing and Age-Related Disease, researchers have confirmed a link between smoking and the acceleration of aging — in part because of the triggering of an inflammatory response that will absolutely make someone look much older than the number of candles on their birthday cake says they are.

Presidents can look old but still be healthy

When the University of Illinois's Jay Olshansky found that presidents only appeared to age... well, what does that mean, exactly? Basically, as he told CNN: "No one dies from gray hair and wrinkles."

After all, some people start seeing gray hair when they're still in their 20s, and according to what Dr. Jennifer Chwalek told Business Insider, the main thing that determines when and how fast a person's going to go gray is genetics. Now, what does that mean for presidents? Basically, that not only is a short life span not in their future, but that some of the lifestyle choices they make can keep them feeling healthy, even when they're still in a high-stress job.

Ronan Factora, a Cleveland Clinic specialist in geriatric medicine, told The Denver Post that many recent presidents have opted to take the best medicine there is for combating the effects of stress: exercise. Barack Obama (pictured) was well-known for workouts that included everything from runs on the treadmill to basketball, while some — like Clinton and Carter — stuck to the jogging, and George W. Bush switched to cycling when his knees didn't allow him to run any more. It was 4-mile runs and exercising with the Marines for George HW Bush, and horseback riding for Reagan. It's about more than getting in shape, experts say: it's about increasing blood flow and getting all the benefits — including increased brain activity — that come from that.

How old should a president elect be?

In recent elections, age has been a huge deal. Should it be? How old is too old to run for — and be elected — president? In 2019, Olshansky had this to say (via EurekAlert) based on his research into aging and the presidency: "Age is just a number. This research for the first time provides science-based calculations that show that the age of a candidate should not be considered at all."

Olshansky and his team took 27 then-current candidates for the presidency — including Bernie Sanders (77), Joe Biden (76), Donald Trump (73, pictured), and Elizabeth Warren (70) — and compared them to national data on things like lifespan and healthspan. In spite of the fact that 2019 polls from the Economist and YouGov found that about 40 percent of people thought someone in their 70s was too old to be president, the scientific answer was that "chronological age itself should not be used as a sole disqualifier to run for or become president."

Instead, Olshansky suggests we realign our thinking to this: "How healthy is the candidate, regardless of their age?"