The Grand Guignol: The Crazy True Story Of The Theater Of Horror

For decades, many media critics have decried the prevalence of graphic violence in entertainment. Horror movies especially have come under fire as a corrupting influence. Blamed for a variety of social ills ranging from an overall cultural degeneracy to inspiring actual murder, horror, and specifically the overt use of blood and gore in the genre, might initially seem like a uniquely modern issue.

In The Monster Show: A Cultural History of Horror, author and genre historian David J. Skal counters such assertions as critical elitism and political pearl-clutching that fails to take in the function of the grotesque beyond mere exploitation. Nor do such arguments take history into account. Although detractors may long for the return of some mythical era of "good, wholesome entertainment," the fact remains that the grotesque and the arts have long been intertwined.

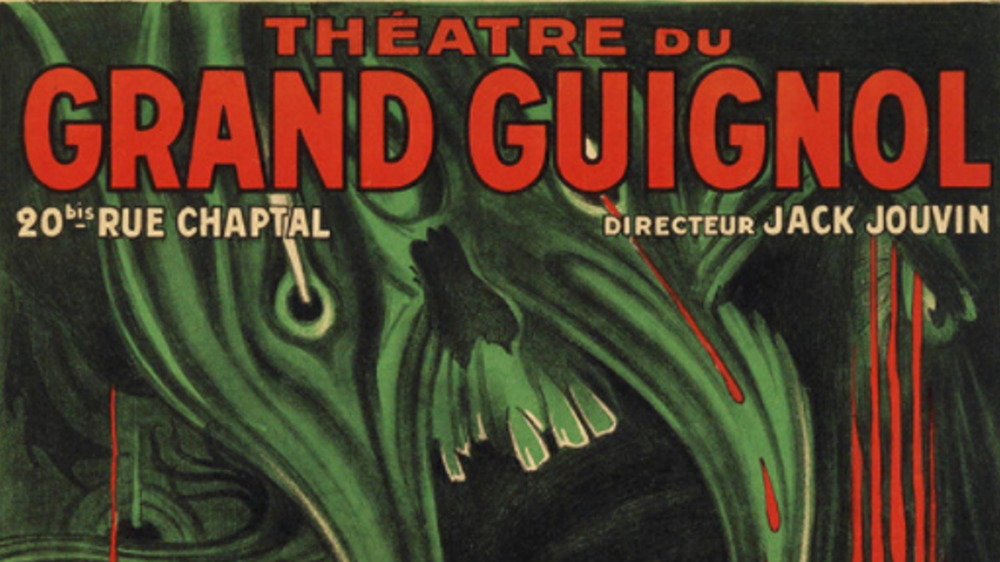

Case in point is Le Théâtre du Grand-Guignol which, beginning in 1897, brought unseemly subjects and stomach-turning gore to the Paris stage. At its height of popularity before the Second World War, the theater attracted celebrities and royalty, who thrilled to horrific acts of murder, mayhem, and dismemberment. Yet, unable to compete with the real-life terrors of the mid-20th century, it faced its final curtain in 1962. Over half a century since its closing, the Grand Guignol continues to fascinate scholars, writers, and lovers of the bizarre. This is the crazy true story of Paris' legendary theater of horror.

The origins of the Grand Guignol

Translated from French, "Grand Guignol" means "big puppet show," or more accurately "puppet show for adults." The word "Guignol," specifically, refers to a character popular in the politically charged puppet theater of the Lyon region of France. Somewhat erroneously compared to England's famous Punch and Judy shows, the original Guignol plays were often filled with social commentary, with the character of Guignol appearing as an advocate for the rights of exploited silk workers, as noted by GrandGuignol.com. Consequently, the puppet shows were often censored and under police scrutiny during Napoleon III's reign. Still popular in France, Guignol has lost much of its socio-political edge and is considered entertainment for children.

Grand Guignol, on the other hand, is pointedly not for younger audiences. Dealing with themes of crime, murder, insanity, and the seedier side of life, the theatrical style is noted for its use of graphic violence and gory special effects. Although the appellation "Grand Guignol" comes from Le Théâtre du Grand-Guignol, the theater opened in 1897 which popularized the form, the genre of horrific, violent plays has antecedents in Elizabethan and Jacobean revenge tragedies, including such works as Shakespeare's notoriously blood-drenched Titus Andronicus.

"Grand Guignol" has since become a catch-all term for any violent or gory art or literature, with the modern slasher and "toture-porn" subgenres noted as modern versions of the form.

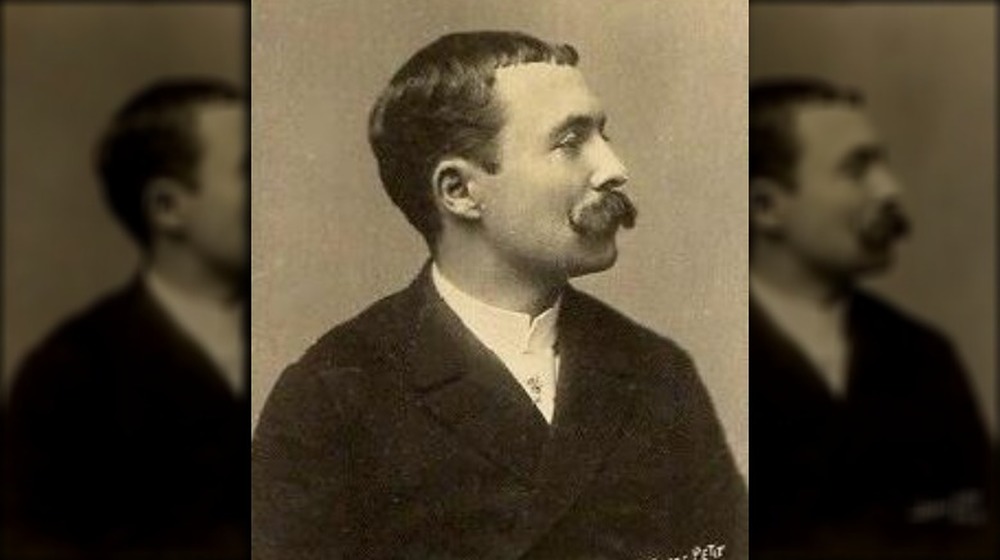

Oscar Méténier and naturalism

Playwright and novelist Oscar Méténier was born on January 7, 1859, in Sancoins, France. The son of a police commissioner, Méténier followed his father into law enforcement as secretary to the commissariat of la Tour Saint-Jacques in Paris.

Méténier's position, which included such duties as accompanying condemned prisoners to the guillotine, gave him a unique perspective of the Parisian underworld, which he incorporated into his stories and plays. An adherent of naturalism, a school of thought that maintains that the universe is governed by natural laws rather than supernatural influence, he focused on the brutality of existence among the dregs of society, seeing in their company a truth absent in the artifice of wealth and propriety. As quoted by Daniel Gerould, author of Comédie Rosse: From the Théâtre Libre to the Grand Guignol, Méténier declared, "There is no absolute honesty... I would go even further — In the strict sense of the word, virtue is a myth... "

In 1897, Méténier purchased the smallest theater in Paris with the sole intent of bringing naturalist drama to the stage. Located in a cul-de-sac in Paris' Pigalle section, the red-light district that's also home to the famous Moulin Rouge, the Grand Guignol began as Méténier's audacious experiment in bringing a realistic depiction of poverty, crime, and violence among the lower classes. However, upon his departure as director in 1893, the theater began a transformation into something much more terrifying.

The Grand Guignol's architecture and atmosphere

The building once known as Le Théâtre du Grand-Guignol seems custom-made to house a theater of horrors. Originally the chapel of a deconsecrated convent, the building seated fewer than 300 people, which must have provided patrons an intimate, if not claustrophobic, encounter with the macabre. Signs of the theater's former function remained ironically in place. Just above its orchestra hung two immense wooden angels, providing an ironic counterpoint to the gruesome events on the stage. Even its small, iron-railed boxes, which could easily be mistaken for confessionals, evoked the theater's ecclesiastical past.

According to the article "The Grand-Guignol: Aspects of Theory and Practice," appearing in the Autumn 2000 issue of Theatre Research International, the theater's location in Pigalle was integral to its overall effect. Authors Richard J. Hand and Michael Wilson write, "To this day the area is seedy and evocative, and the walk down the cobblestoned impasse Chaptal to the closed doors of the theatre is atmospheric and eerie. Spectators who visited the Grand-Guignol recall the drama of the journey to the theatre... There was a sense of a journey into forbidden territory, into the underbelly of Paris with its promise and danger of sex and violence."

Although Le Théâtre du Grand-Guignol presented its last production decades ago, the building remains. Now home to the International Visual Theatre, the former Grand Guignol building is painted a cheery yellow. Despite its festive exterior, the theater and its environs still evoke a decidedly sinister atmosphere.

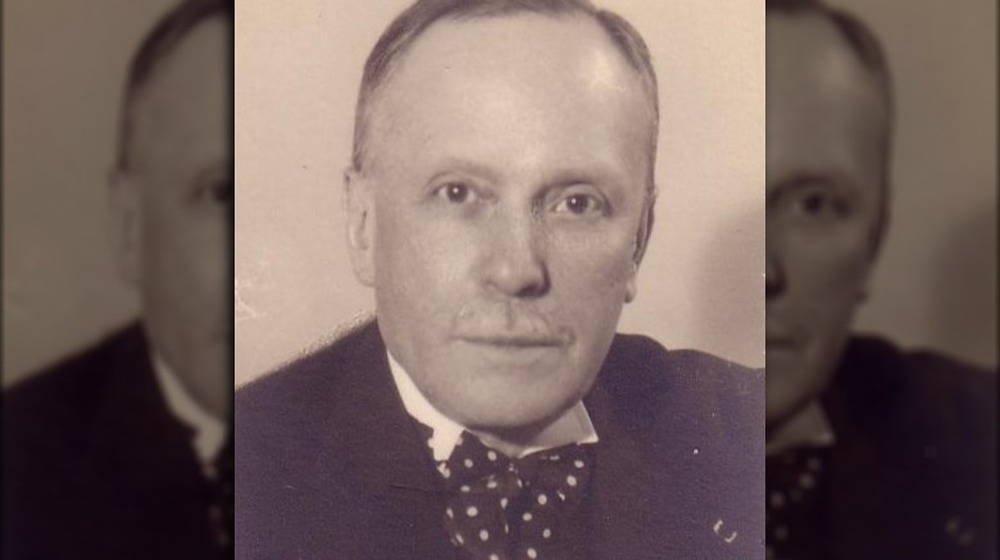

Max Maurey's house of horrors

In 1898, Oscar Méténier stepped down as the Grand Guignol's director. Although the theater was an immediate hit with Parisian audiences, it would gain its reputation for guts and gore under the stewardship of its next director, Max Maurey. What Maurey lacked in literary clout, he made up for with practical theatrical experience and showmanship.

Rebranding the Grand Guignol as a "house of horrors," Maurey replaced Méténier's gritty, socially conscious fare with lurid exploitation, bloody special effects, and an emphasis on the macabre. Featuring plays with such titles as The Garden of Torture, The Merchant of Corpses, and The Castle of Slow Death, Maurey's Grand Guignol treated patrons to an audacious spectacle of amputated limbs, gouged eyes, simulated surgeries, severed tongues, and dripping entrails.

A born entertainer, Max Maurey brought P.T. Barnum-style ballyhoo and promotion to the Grand Guignol. Prefiguring mid-century cinematic showmen such as schlockmeister William Castle, who would utilize some of the same methods to promote his horror films in the late 1950s and '60s, Maurey employed gimmicks and clever exploitation of the press to pack the Grand Guignol with audiences looking for gruesome thrills. As chronicled by author Harold Schecter in his 2005 book Savage Pastimes: A Cultural History of Violent Entertainment, Maurey took out ads in Paris newspapers showing patrons receiving medical examinations before entering the theater and hired a physician to tend to members of the audience who might collapse from shock.

Camille Choisy and The many deaths of Paula Maxa

Camille Choisy replaced Max Maurey as the Grand Guignol's director in 1915. With Choisy came a new emphasis on stagecraft, lighting, and sound. In his pursuit of realism, Choisy went as far as purchasing a fully equipped operating room for use in a play.

In 1917, Choisy hired the Grand Guignol's first breakout star. As recounted by authors Agnès Pierron and Deborah Treisman in their article "The House of Horrors," appearing in the summer 1996 issue of Grand Street, actress Paula Maxa captured the imaginations of Grand Guignol patrons to become the "Sarah Bernhardt of the impasse Chaptal." She would soon come to be known by a far more fitting moniker: "the most assassinated woman in the world."

According to Pierron and Treisman, Paula Maxa was "killed" more than 10,000 times onstage. "During her career at the Grand-Guignol, Maxa [...] was subjected to a range of tortures unique in theatrical history," Pierron and Treisman write. "She was shot with a rifle and with a revolver, scalped, strangled, disemboweled, guillotined, hanged, quartered, burned, cut apart with surgical tools and lancets, cut into eighty-three pieces by an invisible Spanish dagger, stung by a scorpion, poisoned with arsenic, devoured by a puma, strangled by a pearl necklace, and whipped."

A highly fictionalized Paula Maxa, portrayed by Anna Mouglalis, is the subject of the 2018 Netflix film The Most Assassinated Woman in the World. A mystery concerning a serial killer loose in the Grand Guignol, the film partially recreates some of the theater's most notorious plays.

Hot and cold showers: the plays of the Grand Guignol

A typical evening's entertainment for a patron of the Grand Guignol during the tenures of Maurey and Choisy featured a half-dozen or so one-act plays alternating between gruesome melodramas and sexy farces. Behind the scenes, the contrasting plays were referred to as "hot and cold showers." While the comedies served as titillating palette cleansers, they also punctuated the scenes of horror by lulling the audience into a false sense of security.

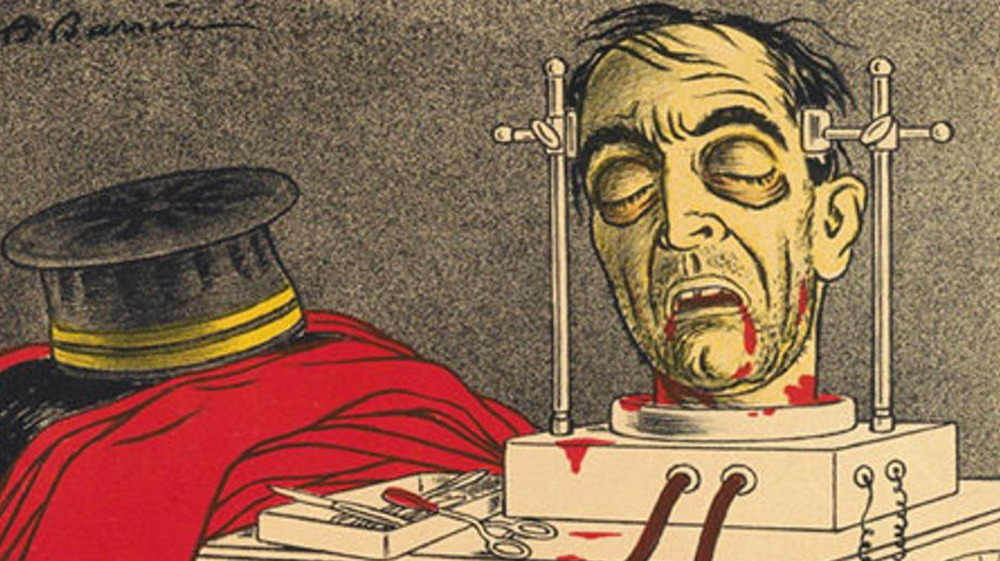

As jarring as the Grand Guignol's violence was, the intent of its writers went beyond sensationalism. For all the blood and gore, a fascination with crossing psychological boundaries characterized the best of the Grand Guignol's productions. Common themes included hypnosis, madness, loss of control, and altered consciousness. "When the Grand-Guignol's playwrights expressed an interest in the guillotine, what fascinated them most were the last convulsions played out on the decapitated face," Pierron and Treisman explain. "What if the head continued to think without the body? The passage from one state to another was the crux of the genre."

Surprisingly, some scholars, such as Richard J. Hand and Michael Wilson, authors of the article "The Grand-Guignol: Aspects of Theory and Practice" suggest that the gore quotient of the Grand Guignol during its peak years may be overstated due to the theater's mystique and the imaginations of its patrons. Citing such sources as extant texts of the plays and the memoirs of Paula Maxa, Hand and Wilson contend that the suggestion of violence was as important as the Grand Guignol's famed bloody effects.

André de Lorde, the Grand Guignol's prince of fear

The Grand Guignol's most celebrated playwright was André de Lorde. Dubbed the "Prince of Terror" by his contemporaries, per Starburst magazine, he composed over 150 plays and a handful of novels — nearly all centering on insanity and violence. Hired by Max Maury in 1901, the prolific playwright and novelist strived for unparalleled accuracy in his work. Collaborating with experts in science, criminology, history, and psychology, de Lorde frequently enlisted the aid of his therapist, experimental psychologist Alfred Binet, in his writing. A pioneer of modern psychology, Binet co-created the Binet-Simon Scale, the first practical IQ test. Consequently, realistic depictions of madness and deviance permeate de Lorde's work.

Among de Lorde's most outrageous Grand Guignol playlets are L'Homme de la Nuit (The Man of the Night), a terrifying tale of grave robbery and necrophilia, L'Horrible Passion (The Horrible Passion), about a murderous nanny, and Doctor Goudron's System, adapted from Edgar Allan Poe's "The System of Doctor Tarr and Professor Fether" in which murderous inmates take over an insane asylum.

Several of de Lorde's works were adapted for film by some of the silent era's greatest directors. In 1909, de Lorde's At the Telephone was adapted as The Lonely Villa by American filmmaker D.W. Griffith, who would go on to direct the controversial Birth of a Nation and Intolerance. French auteur Maurice Torneur also turned to de Lorde's work, enlisting the playwright to pen the script for his 1914 short horror film Figures de Cire.

Audience reactions

As author Harold Schecter writes in Savage Pastimes: A Cultural History of Violent Entertainment, the shows staged at the Grand Guignol were definitely not for the faint of heart or weak of stomach. Grand Guignol director Max Maurey, the man who replaced Oscar Méténier's seedy slice of life-on-skids dramas with violent tales of torture, sadism, and insanity, judged the success of a production based on the number of audience faintings.

One especially graphic scene in which an actress's eye was gouged out with knitting needles is said to have elicited six simultaneous faintings. The record, however, was 15. Consequently, the lobby stocked a hefty supply of smelling salts. "Audience members passed out with alarming regularity," Schecter writes. "Many of the productions induced even more violent reactions. It was not unusual for customers to bolt from the theater in the middle of a performance and vomit in the alley."

According to a 1957 New York Times feature by P.E. Schneider, the realism of the Grand Guignol's graphic special effects prompted more than one doctor in attendance to rush backstage to offer assistance to the "maimed." Not even the Grand Guignol's house doctor was immune to the theater's gory intensity. "On his first night of duty, a spectator fainted," Schneider writes. "The ushers called for the doctor — in vain. At last, the victim regained consciousness unassisted. The ushers apologized and explained what had happened. Whereupon he smiled wanly and whispered, 'I am the doctor.'"

Grand Guignol à la mode

During its peak popularity in the years between World War I and World War II, attending the Grand Guignol became quite fashionable among the upper class. According to The New York Times, celebrities of the day, South American millionaires, and even royalty decked out in tuxedos and fancy dress could be spotted regularly in the theater's cramped boxes. Romanian king Carol II visited the theater when he was ousted by Prince Nicholas in 1930. As revealed by Mel Gordon, author of The Grand Guignol: Theatre of Fear and Terror, Carol II maintained a private bedroom at the Grand Guignol where he met with his mistress. Prince Nicholas himself visited the Grand Guignol during his subsequent exile. Victoria Eugenie of Battenberg, the wife of Spain's deposed King Alfonso XIII, made the Grand Guignol a regular Halloween pilgrimage.

By 1920, the Grand Guingol had grown so popular that there was an attempt to export the blood-drenched entertainment to England. Opening at London's Little Theatre on the Strand, the British Grand Guignol immediately drew the ire of the Lord Chamberlain. According to an interview with Grand Guignol scholar Richard J. Hand conducted by the BBC, audience interest was high, but the theater couldn't endure the constant interference from censors. "Censorship made it impossible for them, with plays being banned outright or tinkered with by the Lord Chamberlain's office," says Hand. "It was maybe too continental for Britain at that time."

World War II and the Grand Guignol

Jack Jouvin assumed the role of theater director in 1930, according to "The House of Horrors." During Jouvin's seven-year tenure, the theater moved away from its trademark gore to psychological horror, allegedly due to a patron's sudden heart attack. Wanting the spotlight for himself, Jouvin ousted star Paula Maxa.

Two years after Jouvin's departure, France entered World War II. During the war, the Grand Guignol, now under the control of British filmmaker Derek Dundas and his wife Eva Berkson, began to lapse into self-parody as its patented violence and gore became increasingly over-the-top and unbelievable. With France under German occupation, Dundas and Berkson were forced to flee when one of their productions included an unflattering representation of the Nazis.

During and after the war, leaders of both the Axis and Allies forces attended performances at the Grand Guignol. Among them were Nazi leader and war criminal Hermann Goering and United States general George S. Patton, who went to the theater following France's liberation.

The end of the Grand Guignol

The Grand Guignol valiantly forged on for 17 more years after World War II but never reclaimed its earlier glory. By the 1950s, attendance dropped dramatically. It seemed that realities of the war and life under Nazi occupation had made the Grand Guignol's grisly stage plays trite by comparison.

Upon visiting the theater in 1958, author Anais Nin noted its decline in an entry in her diary. "I surrendered myself to the Grand-Guignol, to its venerable filth which used to cause such shivers of horror, which used to petrify us with terror," Nin wrote. "All our nightmares of sadism and perversion were played out on that stage... The theater was empty."

The Grand Guignol closed for good in 1962. "We could never equal Buchenwald," the Grand Guignol's final director, Charles Nonon, told Time. "Before the war, everyone felt that what was happening onstage was impossible. Now we know that these things, and worse, are possible in reality."

The Grand Guignol's legacy of horror

The Grand Guignol casts a long shadow over the modern horror genre. Its mixture of blood and wit can be seen in such horror movies as Herschel Gordon Lewis' notorious 1963 drive-in shocker Blood Feast, Hammer Studios' Dracula revivals, the films of Italian gore maestro Lucio Fulci, and classic slashers like The Texas Chain Saw Massacre and Friday the 13th. As noted by Atlas Obscura, Grand Guignol-style thrills have more recently returned in so-called "torture porn" films such as Saw and The Human Centipede. Le Théâtre du Grand-Guignol also inspired author Anne Rice, who based Théâtre des Vampires, a pivotal location in her novel Interview With the Vampire, on the notorious theater.

In the 21st century, Grand Guignol is making a return to the stage thanks to efforts of experimental theater troupes such as Washington DC's Molotov Theatre Group and the now-defunct Thrillpeddlers of San Francisco. Though the original Grand Guignol fell silent decades ago, its bloody legacy lives forever.