Hidden Secrets Of The Library Of Congress

Most of us don't know a lot about the Library of Congress. It's a library. It's used by Congress. And it's (possibly) the largest library in the world. Beyond that, many people probably don't think too hard about it.

Which is a shame, because the Library of Congress, aside from its sheer size (it holds more than 162 million assets in more than 450 different languages) is pretty fascinating. First and foremost, its existence is comforting, especially in the age of fake news and disinformation — at least there's a repository of knowledge that our elected officials can access as needed. Second, despite being a library, it's actually filled with more than just a lot of dusty old books — the place is jammed full of secrets. After all, the library was established more than two centuries ago in 1800. Since then, it's burned down twice, been expanded several times, and seen 14 Librarians of Congress (a position requiring a presidential appointment).

If you want what's hidden in the stacks down in Washington, D.C., you don't have to book a trip down there and get yourself a Reader Identification Card. Here are 12 of the most interesting secrets of the Library of Congress.

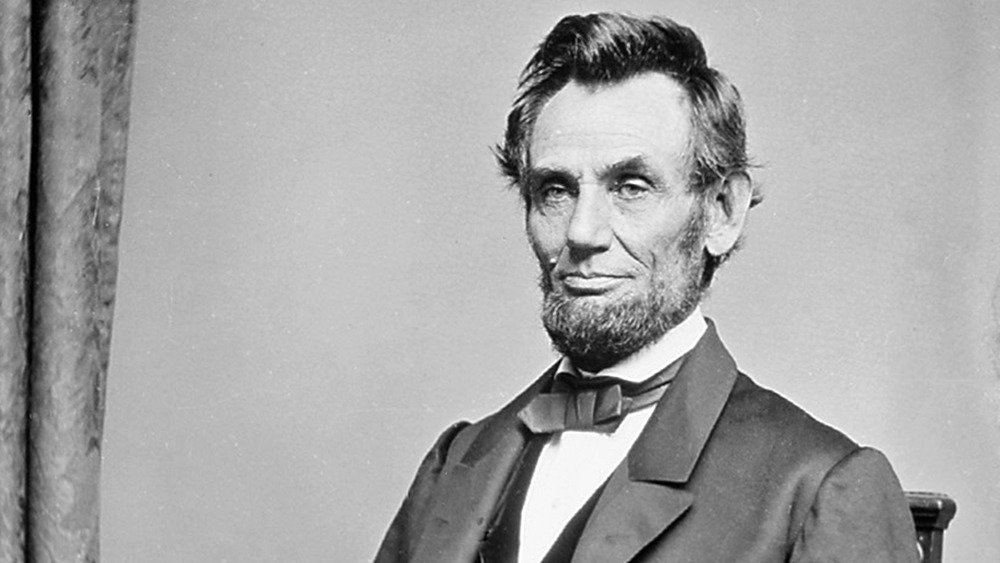

The Library of Congress has Abraham Lincoln's final possessions

When people die under more or less normal circumstances, they have some kind of chance to settle their affairs — writing a will, bequeathing possessions, and making arrangements. When you're suddenly and shockingly assassinated, however, it's a whole other ballgame.

President Abraham Lincoln was shot around 10 p.m. on the of April 14, 1865, and died a few hours later on April 15. According to Biography.com, Lincoln was wearing a Brooks Brothers overcoat. And the president was carrying several items in his pockets, which are actually held at the Library of Congress.

The items are so normal it's painful. There's a pair of glasses that had been repaired with a bit of string. A pocket knife, which many suspect was used to keep those glasses in good repair. A gold watch fob, a monogrammed handkerchief and cufflink. Most interestingly, he also carried a leather wallet containing newspaper clippings following the events of the Civil War — and $5 in Confederate money!

The contents of his pockets were given to his son, Robert, who passed them on to his daughter (Lincoln's granddaughter), Mary Isham. She donated the items to the Library of Congress in 1937 — but bizarrely, no one opened the box until 1976, when the items were finally rediscovered and cataloged.

The Library of Congress holds Rosa Parks' recipe for peanut butter pancakes

The Library of Congress was founded in order to provide information for our elected officials so they can make informed decisions. It also plays a prime role in our copyright laws, holding copies of created works as a matter of record.

But there's another function for the library — preserving our culture and history for future generations. This goes beyond simply recording facts and dates. As anyone who has ever read a history book knows, the best examples are the ones that bring historic figures to life, who make them into real people. So it makes perfect sense that one of the more than 162 million assets the Library of Congress holds is a simple recipe for peanut butter pancakes created by Rosa Parks.

At first this might seem like a random, useless little detail. But as NPR reports, it's actually an incredible piece of the history surrounding Parks. For one thing, the recipe is written on the back of a used banking envelop from when Parks and her husband lived in Detroit — where they moved after receiving death threats. They were struggling financially, so Parks used scrap paper frugally. And the peanut butter is linked to historic efforts to give Black farmers a cash crop other than cotton. Peanuts were originally largely consumed by African slave populations in the South, making this pancake recipe uniquely culturally significant.

The Library of Congress has every tweet

Even when social media isn't self-destructing like Snapchat, there is a tendency to regard it as vanishing. You tweet something in 2018, and it disappears under the wave of the millions of tweets that follow every single week, never to be seen again.

But as The Atlantic notes, someone is actually keeping track of those tweets — and storing them at the Library of Congress. Well, sort of.

This goes back to 2010, when Twitter donated an archive of every tweet to date to the library. The social media company partnered with the library to preserve every tweet for posterity as part of an ambitious project that would eventually see the tweets cataloged and made accessible to the public. That seemed kind of unnecessary in 2010, but as more and more politicians used Twitter for official communications, it's starting to seem prescient.

One problem? The library has been unable to cope with the sheer volume of tweets. There are billions, with more coming every day, and there's simply no plan in place to organize them and make that publicly accessible database a reality. Right now all those tweets are just a jumble of data on servers — so don't worry too much about that embarrassing thing you drunk-tweeted a few years ago. It's buried — for now.

There's a secret Dunkin' Donuts

If you've ever been to the Library of Congress you know two things — It's an absolute unit of a library — in other words, it's huge, with multiple buildings — and many parts of it are kind of boring in terms of design. While some areas of the library are filled with beautiful and interesting art (especially the incredibly beautiful Thomas Jefferson Building), some of it resembles a dull office building you might find anywhere. It's very much designed for serious folks to do serious research, a veritable No Fun Zone.

Except, as Buzzfeed breathlessly reports, there is a hidden gem buried deep inside — a secret Dunkin' Donuts shop. As Buzzfeed details, you have to walk down a lot of impersonal corridors past a lot of blank doors and inscrutable signs in order to find it. And once you do find it, you discover it's quite tiny but always has a line several dozen long, because if you worked at the Library of Congress you'd need tons of sugar and caffeine in order to survive as well.

In fact, the Dunkin' hidden in the bowels of the library is one of a very small list of dining options, which include just a few snack bars. There's also a Subway, located right next to the Dunkin' Donuts, but no one gets excited about a Subway, which is why the Buzzfeed folks didn't even mention it despite sending a photographer there.

The Library of Congress has the smallest children's book ever

You might imagine the Library of Congress is serious business, filled with boring old books and lots of research material no one actually wants to read. But it's also full of amazing curiosities — like the former Guinness World Record holder for smallest children's book in the world.

The book is Old King Cole, printed in 1985. According to Culture24, the book is smaller than a grain of rice (the Library officially lists it as 1/25th of an inch square). That makes it about as small as a period in this sentence at normal resolution and requires a needle or other fine instrument to turn the pages.

Yes, it's a real book — the library has an unbound proof to show how it was printed. The publisher, Gleniffer Press, was launched as a private press by Ian and Helen Macdonald in 1968 and specialized in miniature books like this until they shut down in 2007. Their books are collectibles and very hard to find these days, with many showing up in museums and auction houses.

Sadly, Old King Cole is no longer the smallest book ever — according to the Guinness folks. That honor is currently held by Teeny Ted from Turnip Town, by Malcolm Douglas Chaplin, carved on silicon and just 70 micrometers by 100 micrometers. Still, Old King Cole is pretty small.

There's a tunnel system underground

The Library of Congress is enormous — but it's a working library. Every day people travel from all over the world to consult its collections, and members of Congress constantly send requests for documents. As noted by the House of Representatives, there used to be a complex but efficient underground book delivery system. Reportedly it was capable of delivering books to Congress within five minutes of the request (which was sent via pneumatic tube, which is just cool).

That system was removed 20 years ago — but there's another system of tunnels under the library designed for pedestrians. As Untapped New York reports, these tunnels also contain the office of the Architect of the Capitol, including the mason, carpentry, and machine shops. The government buildings don't maintain themselves, after all — it takes about 2,300 employees to keep everything looking respectable.

The tunnels are used by staff just to get around, especially in bad weather. But they do connect to the Capitol, so they are occasionally used to hand-deliver materials when Congress requests them. In fact, the tunnels are divided into pedestrian side and equipment sides so traffic never gets snarled if someone's pushing a cart of books or some heavy machines.

The musical instruments collection is impressive

You think of libraries, you think of books. Maybe newspapers and periodicals or computers you can use. You probably don't think of musical instruments, much less some of the rarest and most valuable instruments in the world.

As reported by NewsGram, the library's collection is not only pretty huge — it's estimated to hold more than 1,700 wind instruments — it also contains some real rarities. Some of the most notable are legit Stradivari violins, known to be some of the most incredible (and valuable) stringed instruments ever created. Other notable instruments include George Gershwin's piano and the Castelbarco cello (which dates to 1697).

Even more amazing, Book Riot reports that not only does the library host musical recitals and other events, it also makes its rare instruments available to professional musicians and academics. As Scripps Howard Foundation Wire explains, people don't just come to play the instruments, they also come to study them and even copy them.

One of the most important collections in the music section is surprising — flutes. Scientist Dayton C. Miller donated his flute collection in 1941— 1,856 flutes, along with 10,000 pieces of music and 3,000 books. The collection is considered so important it's kept in what's known as the Flute Vault.

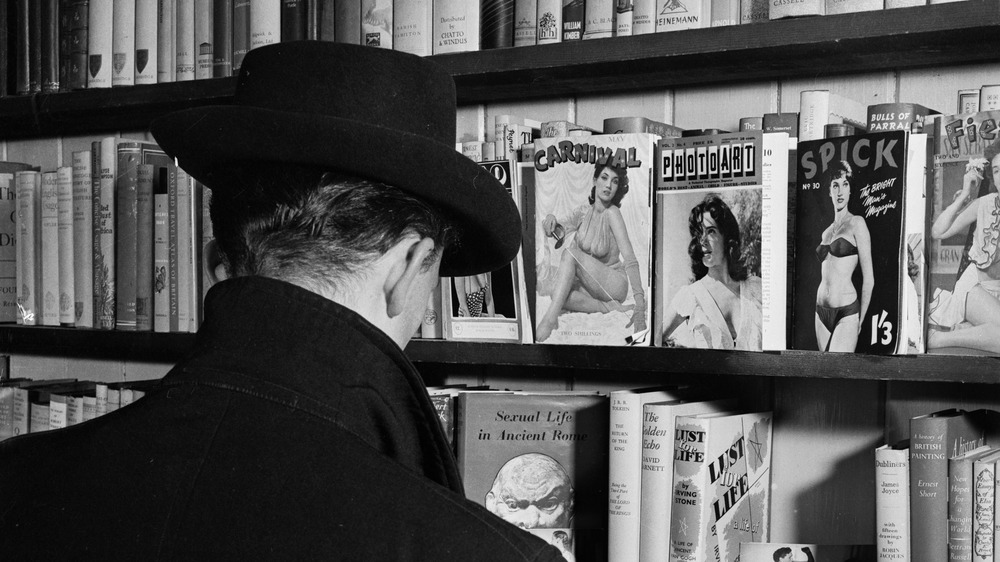

The Library of Congress has pornography

If you're ever at the Library of Congress and someone offers to show you something from the Delta Collection, brace yourself. You're probably about to see something shocking.

As Literary Hub explains, the Delta Collection was once the largest collection of pornography and erotic material in the world. The collection was established to house the obscene materials seized by federal agents over the years, to serve as a database for law enforcement and an official record of a type of literature that often doesn't get a lot of public attention or study. The collection was secret and rarely discussed publicly but served as an official catalog of obscenity that was frequently used by law enforcement and the courts for research and defining what, exactly, was obscene.

Ironically, as The Washington Post reports, the Delta Collection was almost surpassed by the private collection of one of the library's employees — a man named Ralph Whittington. He brought both a passion and a serious academic approach to collecting pornography. Whittington was in charge of the telephone book collection at the library, and when he passed away he donated his music collection. His pornography? He sold that to the Museum of Sex.

The Library of Congress holds the largest collections of comics

The Library of Congress has a mind-bending amount of stuff — more than 162 million assets. That makes it the largest library in the world, so it's not surprising that it holds a few records in terms of the largest collections of specific items. What is a little surprising is what some of those items actually are.

For example, despite the efforts of fans over the decades, the world's largest collection of comic books resides at the Library of Congress. The collection numbers more than 140,000 items. As reported by The Washington Post, the collection was given a huge boost in 2018 when collector Stephen A. Geppi donated his 3,000-plus item collection. His donation included invaluable comics like Action Comics No. 1, the first introduction of Superman, and the original Walt Disney storyboards for the first Mickey Mouse short ever produced.

As noted by Masters in Library Science, the library has the world's largest collection of telephone directories (more than 124,000, with 8,000 new volumes acquired each year). And it also has the largest collection of maps — more than 5.6 million individual examples. The most incredible one is a world map made in 1507 by Martin Waldseemüller — the first map to use the word "America."

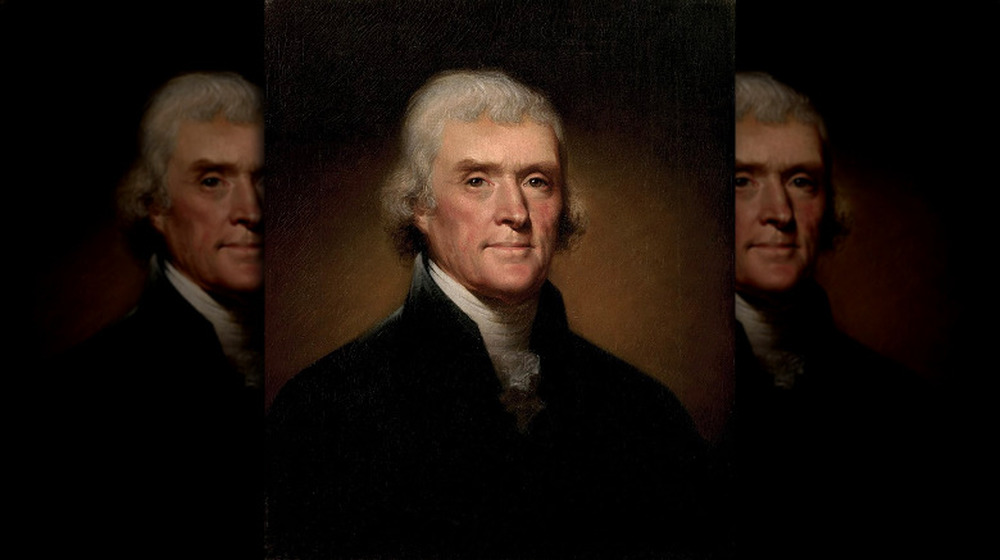

The Library of Congress is recreating Thomas Jefferson's library

The Library of Congress has had a bit of a rough history in some ways. As noted by the encyclopedia Britannica, it was founded in 1800 with an initial budget of $5,000 but was set on fire by the British during the War of 1812, destroying just about the entire collection. Thomas Jefferson saved the day by selling his personal library of 6,487 books to the library for the tidy (and oddly specific) sum of $23,950. That solved the problem until a second, entirely accidental fire destroyed two-thirds of Jefferson's books.

Of course, the library recovered, and today is the largest library in the world, holding millions and millions of books. But the library hasn't forgotten that incredibly valuable collection it bought from Jefferson, and starting in 1998, a quiet effort to replace the lost volumes has been going on. If you visit Jefferson's collection, you'll find the books marked by different color ribbons — green ribbons indicate originals that weren't lost in the 1851 fire, gold indicate replacements that the library has located, and empty boxes mark the books that haven't been replaced yet.

Remarkably, according to NPR, this effort has been wildly successful, and there are only about 250 of Jefferson's books yet to be replaced. That means the library has located more than 4,000 very old and very rare books and quietly added them to its collection.

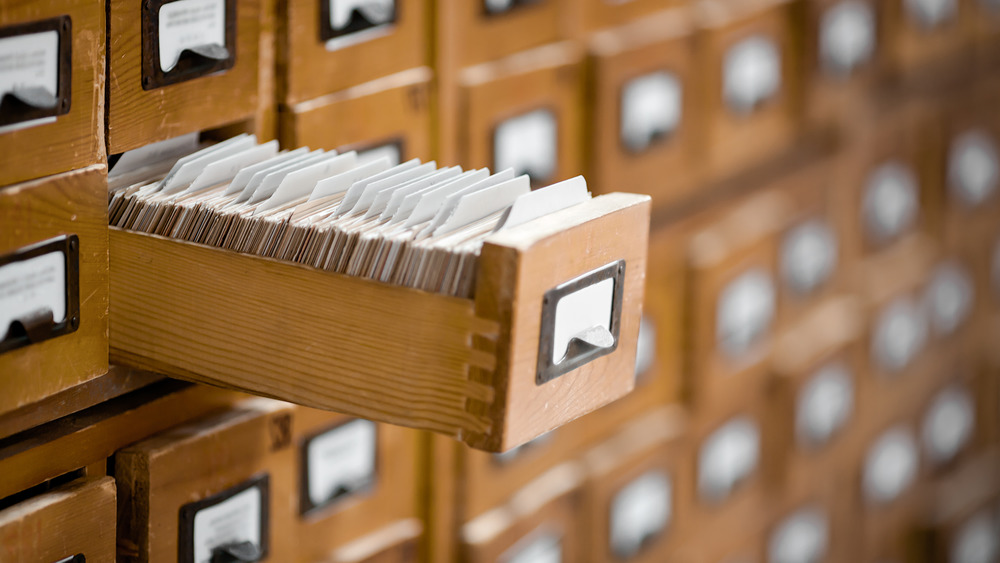

There's an ancient card catalog hidden in there

If you're old enough, you remember card catalogs. Every library had a big cabinet with dozens of small drawers, each drawer containing cards for every book in its collection. If it sounds super primitive and old school, it is, and most modern libraries have long since digitized their records and gotten rid of the card catalogs.

So did the Library of Congress — but as noted by Atlas Obscura, its old card catalog is still there, and it still gets used from time to time.

The catalog was phased out in the late 1970s as the library changed to a new computer system, and it hasn't been updated since 1980. Many people regard the catalog as iconic, and any suggestion that it be removed is met with resistance — but there's a practical reason for this as well. The catalog is a historical document in itself, a record of the oldest and most obscure books in the library's collections and is still useful to academics and researchers.

If you're curious and want to see the catalog but aren't an official researcher, there's an Open House in the Main Reading Room twice a year on Columbus Day and Presidents Day. You can pop in and see how libraries used to run things.

A top-secret FBI interrogation manual was accidentally added

The Library of Congress is a public institution as well as the repository of records for copyright — if you want to officially file for copyright on your books and things, you have to send a copy to the library. So it's not exactly the right place for classified information. But classified information turned up there at least once and wasn't noticed for years.

As reported by The Washington Post, the document in question is an interrogation guide written by an FBI agent. The American Civil Liberties Union has waged a years-long battle with the FBI to gain access to documents like this manual and in 2012 won a significant victory when the FBI agreed to supply redacted versions.

Then, as Mother Jones reports, the author of the manual applied for copyright and sent a copy of the manual to the Library of Congress —despite the fact that works produced by the United States federal government cannot be copyrighted in the first place. And, oh yeah, despite the fact that the whole point of classified documents is to not put them in publicly accessible places. The strangest part is that the FBI agent put the copyright in their own name, claiming credit for something produced by the agency as a whole. The manual remained on the shelves at the library for several years.