False Things You Believe About Spartacus

In 73 BCE, a group of slaves escaped from a Roman gladiatorial school. They armed themselves, freeing more slaves and killing Romans as they went until they were large enough to defeat a Roman army. Which they did. Repeatedly. For nearly three years, tens of thousands of fugitive slaves crashed through Italy, bringing panic to the greatest European empire the world had yet seen. They were led by a man called Spartacus.

It was "the most successful slave revolt in the history of Rome," according to the Ancient History Encyclopedia, and the largest ever until the Zanj Slave Rebellion against the ʿAbbāsid caliphate almost 1,000 years later. Unfortunately, like most slave uprisings throughout history, the Spartacus rebellion failed. But in his failing, Spartacus left behind a story of such bravery that even the Romans he fought commended him. Spartacus has become legend, but legends often lead to false history. Here are some false things you believe about Spartacus.

Myth: We know a lot about Spartacus

Unfortunately, there is technically very little that historians actually know about Spartacus. That may seem strange, given that entire books have been written about him. Spartacus, in this way, was typical of the vast majority of people in antiquity who had no pictures to leave behind, had no statues made, or, even if literate, wrote nothing that survived millennia to be read today.

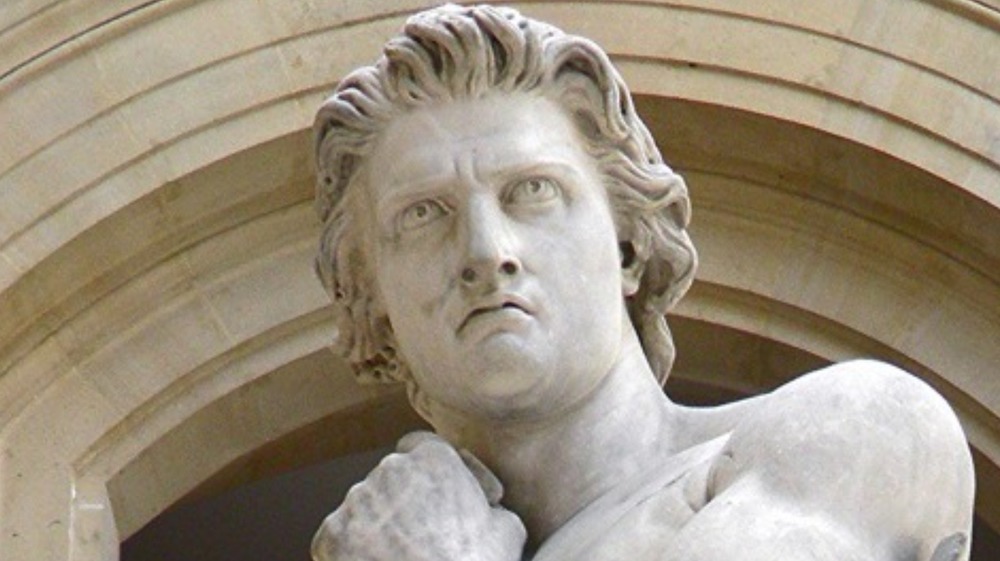

Spartacus has inspired plays, books, films, TV shows, music, poems, and sports teams. Over the last few hundred years, statues have been erected to him all over the world. Karl Marx called Spartacus "the most capital fellow in the whole history of antiquity. A great general [...], of noble character." You'd think that a figure famous enough to spawn one of the most award-winning movies of the last century would leave something behind.

But nothing of what we know about the events of Spartacus' life was written by anyone who actually knew him. None of our ancient sources of information about him and his uprising were written at the time the events happened or by anyone who was there. As the Ancient History Encyclopedia shows, there are basically three ancient authors we rely on (Plutarch, Florus, and Appian), and all of them were born at least a century later. The two earlier historians they relied on were themselves either born decades later or a child when Spartacus died.

Myth: Spartacus wanted to end slavery

Among the precious little that is "known" about Spartacus, according to the Ancient History Encyclopedia, is that he was a Thracian slave in the gladiator school of one Lentulus Batiatus, and one day, he and about 70 other slaves escaped and, over the next few years, garnered enough slaves and allies to defeat the Roman legions in multiple engagements before being killed. From the sparse sources available (via Fordham University), there can only really be guesswork as to what motivated Spartacus and his fellow rebels once they fled. Why they escaped what even Plutarch described as "the cruelty of their master" seems obvious, but there is no evidence that Spartacus intended to end slavery itself, only his own.

Florus said they "were eager to take vengeance on their masters." According to Appian, "Spartacus endeavored to make his way through the Apennines to the Alps and the Gallic country." In other words, they just wanted to escape the country holding them as slaves, and there are conflicting explanations as to why they didn't. Appian says they were cut off by the Romans. Plutarch describes an uprising motivated by a mixture of revenge and escape. While Spartacus "marched his army towards the Alps, intending [...] that every man should go to his own home," the slaves with him disagreed, and "puffed up with their success, would give no obedience to him, but went about and ravaged Italy."

Myth: His name was Spartacus

The only reason Spartacus' name is known is because other people wrote about him. It should be remembered that none of those people met him — and considering the gruesome fate of everyone who fought with him, it would be unlikely they could ever have spoken to any of his friends. So what would those people know of him? They obviously didn't know his family name or didn't care enough to include it. What if Spartacus wasn't even his name?

Historian and archaeologist Ralph Häussler reminds us that it was common in many slave-holding societies for newly purchased slaves to be renamed by their owners and that gladiators commonly had stage names. And, if the ancient sources are to be believed, Spartacus hailed from Thrace, where Professor Häussler says that there was a "Thracian royal dynasty, commonly called the Spartocidae, founded by a certain Spartokos/Spartakos I." Spartacus may have been a stage name given to him at the gladiatorial school.

It is also possible that his Roman historians gave him this name to establish a proper pedigree for this lowly slave who defied great Rome. Plutarch described Spartacus as a man of "high spirit," "valiant," and "more of a Grecian than the people of his country usually are" (high praise from a Roman). How else to explain your defeat unless your enemy was descended from greatness?

Myth: Spartacus was born a slave

Slavery in ancient Rome was a far more complicated institution than the racially categorized one most Americans are familiar with. As PBS describes it, most slaves were foreigners, they could be any color, and generally, Roman slaves were not born in that condition. Neither was Spartacus. "The reality," explains historian Barry Strauss, "is Spartacus was an allied soldier who fought in the Roman army."

Plutarch said he was "a Thracian of one of the nomad tribes" who somehow "came to be sold at Rome," while Appian states outright that, "Spartacus, a Thracian by birth [...] had once served as a soldier with the Romans, but had since been a prisoner and sold for a gladiator." As for the Thracians, both the Greeks and Romans regarded them as "superior fighters," says the Encyclopedia Britannica. "Their soldiers were valued as mercenaries, particularly by the Macedonians and Romans."

Spartacus' fame in the modern age owes a lot to the hugely successful book and film made about him in the mid-20th century. Even though blacklisted author Howard Fast put a lot of research into his likewise-blacklisted novel upon which the movie was based (luckily for him, the prison in which he wrote it had a good library), it shouldn't be too surprising that the movie got a few more things wrong than his book did.

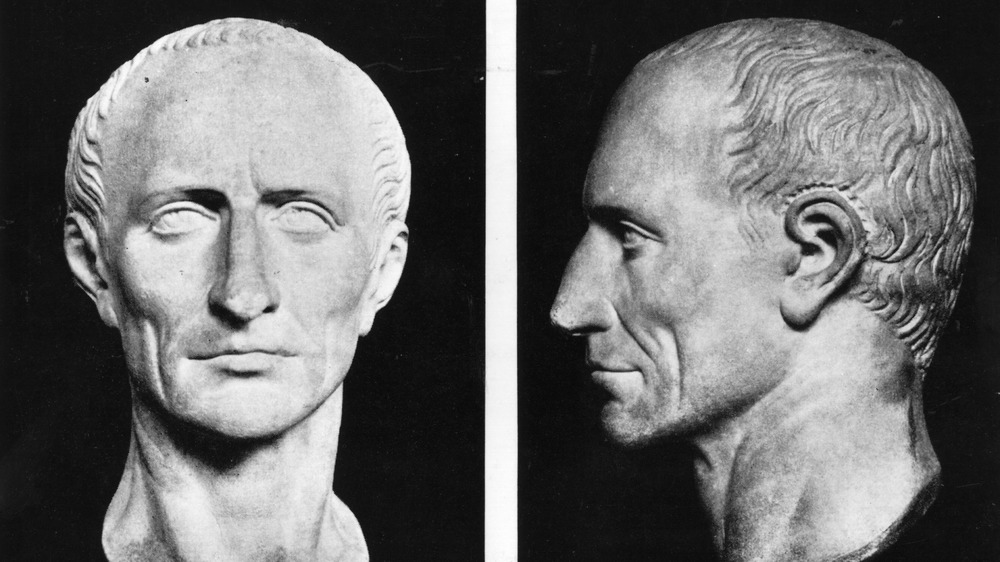

Myth: Spartacus knew Julius Caesar

Julius Caesar is one of the most famous people to have ever lived. His name ended up such a symbol of power that for the next 1,500 years, until the fall of Constantinople in 1453, Roman emperors would adopt his name as their title. Dozens of languages today can trace their word for "emperor" to Caesar, the Saturday Morning Post explains, from the German "kaiser" to the Russian "czar." A more famous Roman would be hard to find. From the Bard's famous 500-year-old biographical play to a recurring character in one of the most-read comics in the world to the famous Kirk Douglas movie and recent Starz series about Spartacus, Julius Caesar is authentic Rome.

Unfortunately, there is nothing authentic about Caesar's placement in the story of Spartacus. In both the Starz TV show and the classic Stanley Kubrick movie, Julius Caesar was shown as being involved in confronting Spartacus. Although Caesar was alive at the time and was friends with General Crassus, and would later form the triumvirate with him, Julius had absolutely nothing to do with the Spartacus incident. As San Jose State University's timeline of Caesar's life shows, when Spartacus began his revolt, Julius was fighting the King of Pontus in Anatolia. As one of the Starz show writers told TV Guide, "everything in the show with Caesar is fictional."

Myth: Spartacus was crucified

After three years of bloody fighting, the Romans had finally boxed Spartacus and his slaves in. The resulting battle was a decisive defeat for the slaves. As Appian wrote, "So great was the slaughter that it was impossible to count them. The Roman loss was about 1,000." The final 6,000 rebel slaves were captured. General Crassus ordered his men to take the survivors and have them, according to Appian, "crucified along the whole road from Capua to Rome" — 6,000 people nailed to wooden crosses and left to die, for miles. In the final scene of Stanley Kubrick's Spartacus, the titular hero looks from his crucifix upon his wife and child as they escape.

As epic of a scene as it was, however, it was pure Hollywood fabrication, according to Daily History. The primary sources are unanimous in stating that Spartacus died in battle. According to Plutarch, "[S]urrounded by the enemy, bravely defending himself, [he] was cut in pieces." Florus gives a bit more detail: "As was fitting for a gladiator captain, they fought without sparing themselves. Spartacus himself, fighting with the utmost bravery in the front of the battle, fell as became their general." Appian states plainly: "The body of Spartacus was not found."

Myth: "I am Spartacus!"

The ancient sources all agree that Spartacus was killed in action, his body never found, which poses a problem for the most epic scene of Kubrick's epic film. In the movie, after the final battle, the surviving slaves are taken prisoner and General Crassus is searching among the survivors for the slave leader. In a stirring scene of solidarity and sacrifice, his men each stand up and declare to the Romans, "I am Spartacus!" preventing the Romans from discovering the real Spartacus.

Although fictional, "I am Spartacus!" became a meme before we knew what memes were. It was mocked by the genius satirists of Monty Python in their Life of Brian film and given homage in countless books, comics, TV shows, and movies. At the end of Spike Lee's own epic 1992 film, Malcolm X, African and American Black children say to the screen: "I am Malcolm X."

Just like Spike Lee's Spartacus tribute was a critique of America's racial politics in the 1990s, the original scene criticized American politics of the 1950s. Hollywood was cowed by the anti-Communist fervor gripping the nation after artists, directors, and producers had been hauled before Congress and accused of being dirty commies. "I am Spartacus!" was a blatant dig at the artists and other industry people who collaborated with the Hollywood blacklist of the McCarthy era. The writer of Spartacus was on the blacklist himself, and in many ways, the film was designed to challenge it.

Myth: Spartacus led Rome's sole slave revolt

Spartacus was not the first, but rather the last, Roman slave to lead a general revolt against his masters. He led the final installment in the Servile Wars, a series of slave uprisings ("servile" coming from the Latin for "slave": servus) taking place over 70 years. Spartacus was, however, the only slave leader that Roman historians treated with consistent respect in their writing.

In 135 BCE, Sicily was awash with slaves, and they were treated terribly. They fled their masters, leaving "bloodshed everywhere, since the brigands were like scattered bands of soldiers." said Greek historian Diodorus Siculus. Finally, one "unmanly" Syrian slave who could allegedly literally breathe fire led Sicily's slaves into revolt. Eunus "would produce fire and flame from his mouth," and for three years, his forces kept Rome's legions at bay before ultimate defeat and the last 20,000 slaves being slaughtered.

Just 30 years later, another uprising would occur when, perversely, some slaves were freed. As part of a distant war effort, the Roman Senate had ordered that no allied nations' citizens could be held in Roman slavery. The governor of Sicily began freeing some 800 people, said Diodurus Siculus, "And all who were in slavery throughout the island were agog with hopes of freedom." Unfortunately, the ineligible slaves got angry, the slaveholders got angry, and the governor rescinded the emancipation proceedings. The second Servile War would last four years.

Myth: Pirates spoiled Spartacus' chance to escape

After three years of traipsing through the Italian countryside liberating slaves and stomping Romans, Spartacus hired some pirates to ferry his band away. In the movie, the Roman general Crassus bribes the pirates to betray Spartacus. Plutarch sort of confirms this account, "But after the pirates had struck a bargain with him [...] they deceived him and sailed away." Pirate treachery ended their hopes of freedom, goes the story.

But that's only one story. Florus makes no record of the pirates, saying that Spartacus attempted "to escape to Sicily, but having no ships, and having in vain tried [...] to sail on rafts made of hurdles and casks tied together with twigs." That was as successful as you might imagine, and the rest of the story remains the same: Everybody dies. Appian simply states that "they tried to pass over to Sicily."

Sadly, it's probable that Spartacus' group invited their grisly end when they chose not to escape through the Alps when they had the chance the year prior. After their latest victory against the Romans, Spartacus headed north to escape through the Alps, but that isn't what happened. They turned south instead, and why they did so is uncertain. "Many theories have been proposed, but the best explanation was already hinted at in the ancient sources. Spartacus' own men probably vetoed him," Live Science quotes classics professor Barry Strauss. "[S]uccess might have gone to their heads and aroused visions of Rome in flames."

Myth: Spartacus was the only leader of the slave revolt

Spartacus may not actually even have been the sole leader of the fugitive slaves. All the sources agree that he at least shared power with two other escapees from the gladiatorial school. "Spartacus, Crixus, and Oenomaus, breaking out of the fencing school of Lentulus escaped from Capua." wrote Florus. "And seizing upon a defensible place, they chose three captains," says Plutarch.

Appian referred to Crixus and Oenomaus as "subordinate officers" to Spartacus but depicts Crixus as leading his own army, which was crushed. Whether that means he was just a field commander in the slave forces or a co-leader is unsure. One thing is certain: Spartacus was not the sole decision-maker for the group, a fact neatly demonstrated by their rejection of his Alpine escape plan.

Then there's Spartacus' wife. She was a Thracian tough-as-nails country gal and now-former slave, and she was also "a kind of prophetess," says Plutarch. Her name is lost to time, but she may have actually inspired the revolt in the first place, says Cornell professor Barry Strauss. As Spartacus slept one night, according to Plutarch, a snake coiled around his face. His wife said "it was a sign portending great and formidable power to him with no happy event." Says Professor Strauss, "Thracians valued the religious authority of women and they set great store by prophecy, making it likely that Spartacus's wife was a respected figure."

Myth: the slaves only wanted freedom

All three of the Servile Wars, aside from the players remaining essentially the same (slaves vs. Romans), were started for functionally the same reason. The Romans treated their slaves worse than dirt, and enough of them got tired of it that they fought back. At the same time, each of the Roman Slave Wars lasted for years because freedom wasn't the only thing on the minds of the fugitive slaves — they wanted revenge. Wanting one's freedom is a universally understandable motivation, and most people would likely be sympathetic to the desire for vengeance which may motivate a newly freed slave.

Still, as products of the brutal time in which they lived, the freed slaves reportedly committed all manner of atrocities. According to Appian, they sacked cities, "plundered the neighboring country," and basically did what any group of Iron Age marauders would do: rape, murder, and pillage. After Crixus' death in battle, Spartacus took 300 captured Roman troops and, kind of hypocritically, "obliged the prisoners to fight with arms," according to Florus. Then Spartacus, says Appian, "burned all his useless material, killed all his prisoners, and butchered his pack animals in order to expedite his movement." To show his men what would happen if they didn't fight, he crucified one Roman prisoner before a battle. Whatever else Spartacus and his men may have been, brutal practicality was among them.

Myth: It was a small uprising

Spartacus' war started as small an affair as can be imagined, as a kitchen brawl. According to Plutarch, 200 slaves had plotted to escape but were discovered. Seventy-eight of them moved fast and "got out of a cook's shop chopping-knives and spits and made their way through the city." Florus seems to contradict him slightly by saying the three slave leaders escaped "with not more than thirty of the same occupation," but it's possible he was counting only gladiators. Either way, fewer than 100 escaped slaves quickly grew to many more times that number.

Appian wrote that after they escaped, "many fugitive slaves and even some freemen from the fields joined Spartacus" and together went a-plundering in the Roman countryside. The Romans quickly assembled a response force, too quickly it turns out, as "the Romans did not consider this a war as yet, but a raid, something like an outbreak of robbery." The slaves did the whipping this time, and, "After this still greater numbers flocked to Spartacus till his army numbered 70,000 men."

The slave army "marched on Rome with 120,000" infantry, says Appian, and though they changed course and didn't attack Rome, "they ravaged, with terrible devastation, Nola and Nuceria, Thurii and Metapontum," as described by Florus. The texts rarely mention the women and probably children that marched with the freedmen, but their inclusion would swell the numbers substantially.