The Real-Life Stories Of Women Who Led Native American Tribes

According to the National Conference fo State Legislatures, there are currently 574 federally recognized Native American tribes. That matter, along with the fact that there are thousands of years of history amongst these many tribes and groups, means that there is a wealth of tales and records of Native American leaders. Given the wide array of cultures involved, it's also worth noting that not every one of these leaders were men. In fact, as the American Museum of Natural History reports, the division of labor by gender often varied quite a bit depending on the tribe in question. Few tribes, even after contact with European settlers, fell totally in line with the hierarchical and patriarchal roles espoused by many whites.

Ultimately, this meant that quite a few Native American women were able to step into considerable leadership roles. From the Iroquois Confederacy of the Northeast, to the Apache of the Southwest, and many people in between, women became chiefs, warriors, shamans, and powerful figures in their own right. Their individual stories span much of recorded history, too, from the early days of British contact to modern women who were elected to lead their tribes. These are the real-life stories of women who led Native American tribes.

Molly Brant was a Mohawk woman who may have taken part in colonial espionage

Like so many Native American leaders of the 18th century and beyond, Konwatsi'tsiaienni, also known as Molly Brant, was caught mediating between a minimum of two cultures. As the Cataraqui Archaeological Research Foundation reports, Brant was born in 1736 as a member of the Mohawk tribe somewhere in the Ohio River Valley. Her parents were registered as Protestant Christians and may well have had their daughter educated in a mission school.

Brant herself eventually became a clan mother and was well involved in tribal politics by the time she was an adult. That political acumen helped Brant when she took up with Sir William Johnson. Johnson was a well-known trader in the region and was eventually appointed superintendent of Indian Affairs for New York while it was still under British control. As the National Park Service reports, he eventually entered into a relationship with Brant. Though she was referred to in records as his "housekeeper," it's clear that her political connections were vital to Johnson's work and their successful trading ventures.

During the American Revolution, Brant allied herself with the British, sending them messages about the movement of colonial troops and arguably engaging in espionage. She was forced to flee to Canada, where the British paid her a military pension after the war. The new United States eventually offered her a hefty payment to return, too, but the loyalist Brant rejected them "with the utmost contempt."

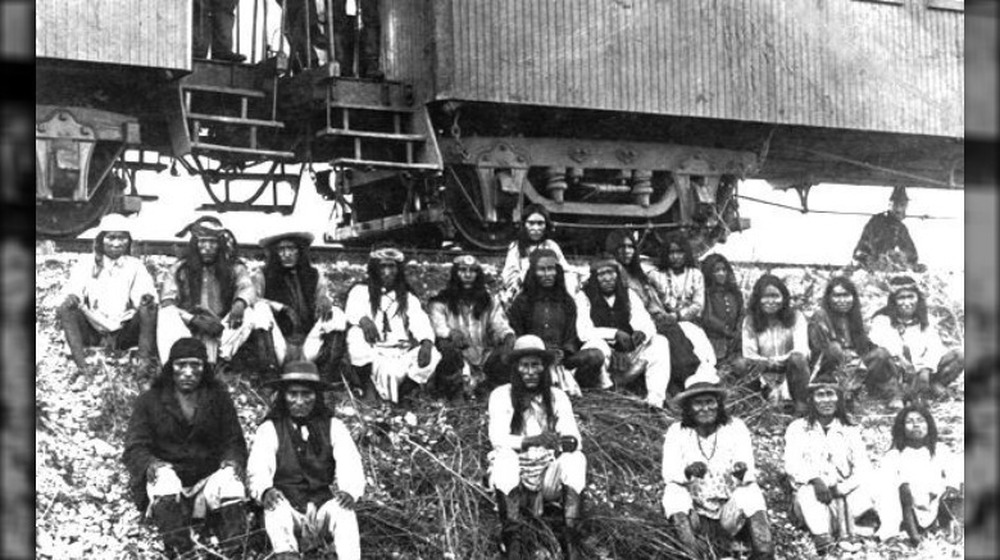

Lozen was an Apache warrior woman

As Mashable reports, Lozen was unique for her time and people. She eschewed traditional gender roles and became both a powerful, respected medicine woman and a warrior. She was, by all accounts, a strategic genius who often rode into battle alongside her brother, Chief Victorio, as they defended Apache land rights against encroachment. Beginning in 1877, Lozen and her brother led the Apache people out of the San Carlos Reservation, also called "Hell's Forty Acres." Lozen eventually teamed up with Geronimo until his surrender in 1885. The U.S. Government apparently considered Lozen dangerous enough to imprison her in Alabama, where she died of tuberculosis in 1887, only 49 years old.

According to Bustle, Lozen was linked to another female warrior, Dahteste. She joined in the fight alongside Lozen and may very well have been linked to her romantically, or at least in a very close relationship. Dahteste was transported to St. Augustine, Fla., after the 1885 surrender, though she eventually returned to New Mexico, refused to speak English again, and, in the words of interviewer Eve Ball, "to the end of her life mourned Lozen."

Wilma Mankiller was the first woman to lead the Cherokee Nation

As principal chief of the Cherokee Nation, Wilma Mankiller was the first woman to lead her tribe. She came to her position after a life of activism complicated by difficult circumstances and chronic health issues. According to the National Women's History Museum, Mankiller was born in Oklahoma in 1945 and moved to California when she was still relatively young. It was there that the 1969 occupation of Alcatraz by Native American activists brought the American Indian Movement to the forefront of Mankiller's life.

She divorced her first husband, who wanted her to remain a quiet housewife, and moved back to Oklahoma in the late 1970s. There, she was involved in a serious car accident that killed her friend and forced Mankiller to recover for a year. She was also diagnosed with myasthenia gravis, a long-term neuromuscular disease that affected her muscle strength.

As per the Oklahoma Historical Society, Mankilller became involved with a number of community initiatives meant to improve the education and living situation of Native American people in Bell, Okla. Eventually, this led to her election as principal chief in July 1987, where she served until 1995. Mankiller died in 2010, proud of her accomplishments as a woman and leader, saying, "But I also want to be remembered for emphasizing the fact that we have indigenous solutions to our problems."

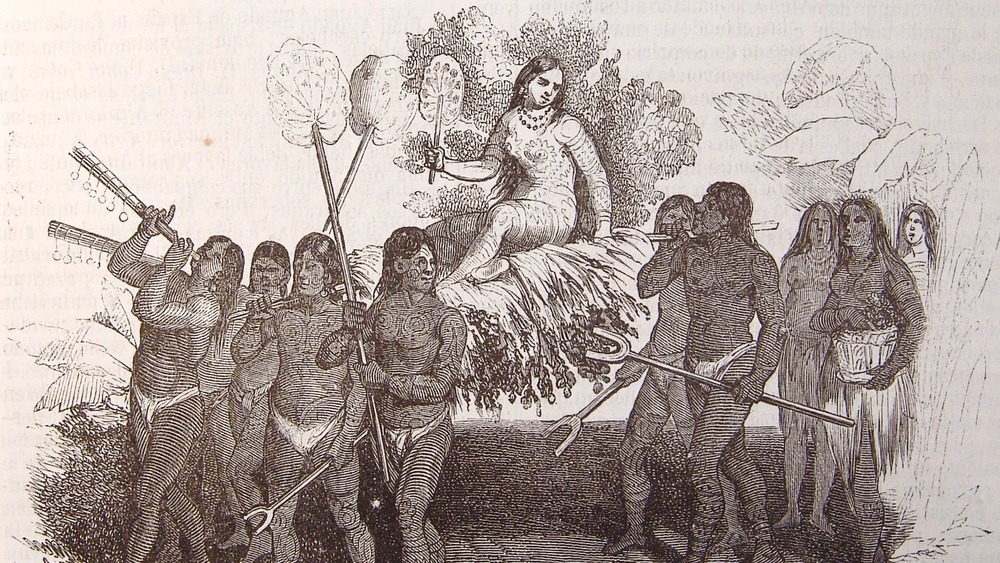

The poetic Anacaona faced off against Spanish conquistadors

Anacaona saw the arrival of Christopher Columbus and Spanish invaders to her land, now modern-day Haiti. She was also, as Rejected Princesses reports, in just such a position to resist them with serious force. Anacaona was also married to a cacique, or chief, and was the sister to another, putting her in the top echelon of Taino society. She had further gained the respect of her people for her artistic accomplishments, which included composing poetry, dances, and all-important oral histories of her people.

Alas, as so many people before and after them, the Taino were hit hard by the conquistadors. When they tried to resist the colonizers, Anacaona's husband, Caonabo, was taken into prison. Anacaona became chief in his stead. Where others fought the Spanish, she attempted to appease them but was eventually betrayed in 1502. That's when Nicolas de Ovando, the appointed governor, gave the order to slaughter nearly all of the caciques, many of whom were burned alive while tied inside a structure.

Anacaona, however, was spared, at least for a short time. Ovando had her transported to Santo Domingo, where she was put on trial. Unsurprisingly, the heavily colonialist court convicted her, and Anacaona was hanged shortly thereafter. She may have gotten some measure of justice when, disgusted by Ovando's actions, Queen Isabella of Spain is said to have demanded his ouster from her own deathbed.

Queen Alliquippa led the Seneca through British contact

By the time most historic records mention Queen Alliquippa of the Seneca nation, she was already a well-established and powerful force amongst the Iroquois people of the Ohio River Valley. The National Park Service reports that a number of accounts from the 18th century describe her as "old," having been born sometime around 1679. That's about all that is known of her early life, though there's plenty of information about her powerful position as an adult and leader.

She even commanded the respect of a then 20-year-old British military officer called George Washington. In 1753, he visited Queen Alliquippa after an unsuccessful meeting with French forces, writing that "I made her a Present of a Match Coat; & a Bottle of rum, which was thought much the best Present of the two" (via National Park Service). Clearly, it was a smart idea to stay on Alliquippa's good side.

Like many other Iroquois leaders, Alliquippa aligned her tribe with the British forces occupying the region. According to History of American Women, she refused to entertain French visitors and was an important British ally during the French and Indian War. That's when she met up again with Washington, now a lieutenant colonel at the besieged Fort Necessity in Pennsylvania. She made it through the 1754 battle there and died later that year.

Eagle Woman mediated between the Sioux and white settlers

Eagle Woman, also known as Wambli Autepewin ("Eagle Woman That All Look At") was born in 1820 in South Dakota, the daughter of a chief. According to the South Dakota Hall of Fame, she moved to Fort Pierre after her 1838 marriage to Honore Picotte, a trader. Though she was married to Picotte for ten years and bore him two children, Picotte left her in 1848. She then married Charles Galpin, another trader, in 1850. Their union was longer-lasting and more useful, as "Mrs. Galpin," as she was known, acted as a hostess and important trade link in the region.

Yet, Eagle Woman was no passive bystander in her own life. As per Britannica, Galpin's death in 1869 led to her own work as a trader. During this time, she became more and more of an important political figure and peacemaker, believing that the Sioux would either have to live alongside whites or be killed altogether.

That already sounds like a backbreaking amount of work, but then, in 1874, gold was discovered in the Black Hills. A flood of hopeful miners entered the region. With the Sioux War of 1876, the government leveraged its position by refusing to supply the reservation until the tribe gave up its gold-rich lands in the Black Hills. Eagle Woman became a prominent negotiator and translator, though she opposed the treaty herself.

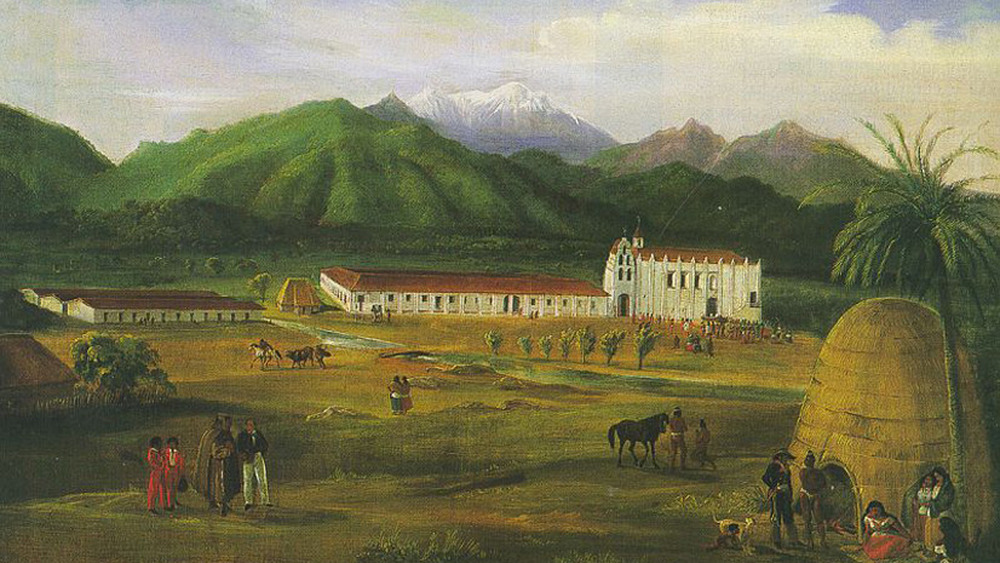

Toypurina led a revolution against the San Gabriel Mission

Though not much is known about Toypurina's life, this medicine woman from 18th century California was clearly a woman of great power. And though, as the The Los Angeles Times reports, the Spanish missionaries tried their best to depict her as a near-demonic evildoer, Toypurina is also well-remembered as the brave leader of a native rebellion. She was about 10 years old when the Spanish took the land around her village and turned it into the San Gabriel Mission in 1771. She would have grown into adulthood in the company of missionaries and soldiers, who by turns killed and entrapped the Indigenous people. Those who converted to Christianity were given food, clothing, and other supplies but were also forced into backbreaking labor.

Things reached a breaking point in 1785. That's when Toypurina, by then a powerful shaman and leader, joined forces with a man named Nicolás José. As KCET reports, José was incensed by the missionaries' decision to ban all Native American practices, which they deemed "pagan." Toypurina and José led an attack against the San Gabriel Mission on Oct. 25, 1785. Yet, someone had let the Spanish know ahead of time, and so Toypurina and the rest were met with military resistance.

Toypurina was exiled after a trial and died in 1799. She's since been memorialized as a freedom fighter, having reportedly said during her trial that "I hate the padres and all of you, for living here on my native soil."

Annie Dodge Wauneka worked for the health of the Navajo Nation

A pandemic pushed Annie Dodge Wauneka onto the path that would eventually lead her not only to the leadership of the Navajo Nation but a Presidential Medal of Honor. Born in 1910, as per the National Women's Hall of Fame, Wauneka was only 8 years old when the 1918 influenza pandemic swept through her Arizona community. She caught a relatively mild case and recovered with some immunity, making her able to help other Navajo who were harder hit by the disease. Born to a wealthy family, Wauneka also began to see the widespread poverty and health issues that plagued many in her tribe.

Wauneka began to study public health while also attending tribal council meetings with her father, Utah Women's History reports. She eventually earned a degree in public health and won election to the Navajo Tribal Council, once defeating her own husband in a bid for re-election to her council seat. With her degree, Wauneka took over the health committee for the tribe and began translating medical terminology from English into Navajo in an effort to improve public health alongside her sanitation and education initiatives. For her extensive work, she was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1963 and served on advisory boards for both the U.S. Surgeon General and the U.S. Public Health Service.

Weetamoo fought for the Pocasset Wampanoag people

As a female sachem, or chief, Weetamoo joined her Pocasset Tribe with the other native people fighting in the 1675 King Philip's War, an armed uprising against colonists and their allies. According to Women & the American Story, she would have been born sometime around 1640 in what's now known as Cap Cod, Mass. Her father was also a sachem and leader in the wider Wampanoag Confederacy of tribes in the area.

By the time Weetamoo came to power, her tribe and many others were in dire straits. With up to 90% of the Wampanoags dead from European diseases, other tribes began to eye their territory. Weetamoo tried to shore up power by marrying other Wampanoag leaders and cozying up to the English settlers, who helped to fend off other tribes.

Weetamoo soon found that the British were increasingly demanding and suspicious of the native people. Metacom, Weetamoo's brother-in-law, began to raid English communities in 1675, starting off the conflict known as King Philip's War, or Metacom's War. This proved to be a turning point for Weetamoo, who ditched ties to the British. Yet, the war didn't help Weetamoo or her people. She's said to have drowned during a river crossing in 1676. When the British desecrated her remains, it was the final blow in a dramatic and oftentimes tragic life.

Alice Brown Davis led the Seminole of Oklahoma

Alice Brown Davis' life took her on a long, winding road to the head of Oklahoma's Seminole Tribe. As per the Oklahoma Historical Society, she was born in 1852 and orphaned in 1867, when both of her parents died in a cholera epidemic. After her 1874 marriage, it seemed as if Davis would be comfortably and rather unremarkably situated as a business owner, teacher, rancher, and postmaster, among other things. Following her divorce in 1898, she also became a single mother in addition to running various business ventures and even serving as the superintendent of the Emahaka Female Academy.

All of this eventually garnered Davis quite a bit of attention. As the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma reports, she was appointed chief of the Seminole tribe in 1922, by President Warren G. Harding. She was to be the first woman to officially lead her tribe as a chief. It was initially controversial, as previous chiefs were chosen via election and not simply put into office by a distant president. Yet, Davis proved devoted to tribal self-governance and worked to secure the tribe's land rights in the face of dwindling legal protections, earning her much respect and admiration upon her death in 1935.

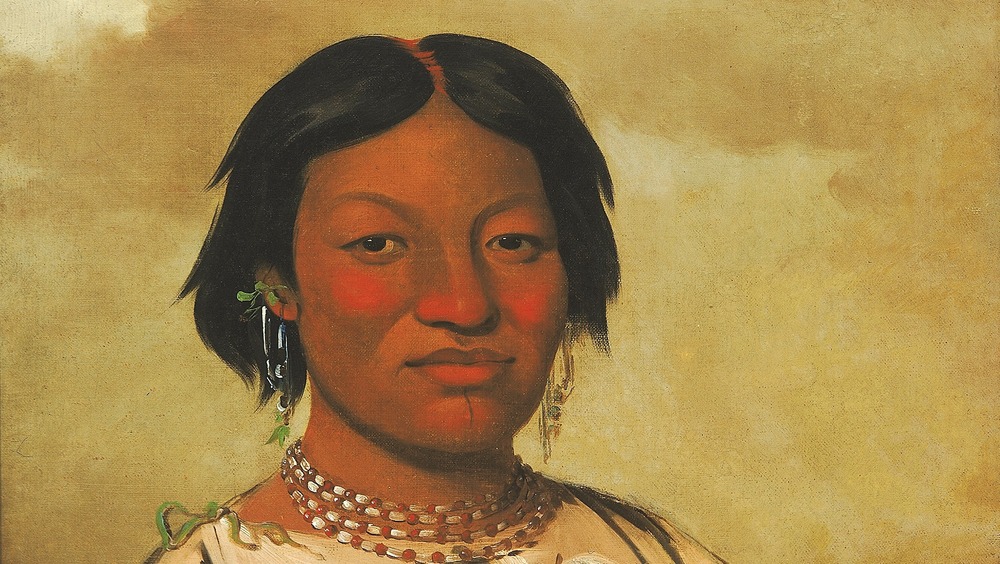

Woman Chief was a famous Crow warrior and leader

Biawacheeitche, known in English as "Woman Chief," was a woman who was widely recognized as a powerful warrior and member of the Council of Chiefs of the Crow Tribe. Women's History Matters reports that she was born in 1806 in the Gros Ventre Tribe of Montana. As her story goes, she was captured as a child by a Crow warrior seeking to replace his own lost son. The warrior either raised her to take on the departed son's warrior role or, as artist Ria Brodell points out, she may have been inclined to take on more traditionally male tasks herself.

Woman Chief, as she came to be known, did indeed take part in battles and gained renown for her military skill. She also attracted the attention of Western observers, who tended to exoticize her very real achievements. They were fascinated by a woman who, though she typically dressed in standard feminine garb for Crow people, also carried weapons and commanded respect for more than her homemaking skills. Western observers may also have been shocked by Woman Chief's personal life, which included multiple wives but no husbands. James Beckworth, a freed slave and mountain scout, even said that he had proposed marriage to her. In his account, she promised that she would accept his proposal when the pine leaves turned yellow. It was only later that Beckworth realized the pine leaves would indeed never turn their colors.

Nancy Ward was a powerful Cherokee negotiator and leader

As a powerful and respected leader of the Cherokee Wolf Clan, Nancy Ward, also known as Nanyehi ("She Who Walks Among The Spirits"), eventually became known as Ghigau ("Beloved Woman"), and for good reason. According to Women & the American Story, she was born in 1738, when British forces had made inroads into the North American continent and were generally causing a fair amount of intrigue and upset for Native American tribes everywhere they went.

Ward also had exclusive rights to decide just what happened to prisoners taken in battles and raids. As such, she was known to have spared captives and, as someone who tended towards working with the whites, released some to warn other settlers of an impending attack. She once approached peace talks with an appeal to let the women on both sides work things out, which struck the whites as odd at best, though it was apparently a natural suggestion for the Cherokee.

Ward also helped to introduce new ways for the tribe to survive and make money in the quickly changing world of 18th century Tennessee. These included some now very controversial moves, like owning slaves, as well as textile production and dairy farming. Still, Ward would have witnessed the inexorable encroachment into Cherokee territory as more and more Indigenous people were pressured into selling their land to settlers.