Christman Genipperteinga: The German Serial Killer Who Probably Didn't Exist

There's no denying the fact that serial killers are fascinating. It's a weird thing to be captivated by, but just check out the lineup of any streaming service to see just how popular true — and fictional — crime dramas are.

Criminologist Scott Bonn says (via Psychology Today) that there's a few things at work here. For starters, most people can't fathom what's going on in someone who decides they're going to kill over and over again, and it's human nature to want to know things. Serial killers are, for many, the ultimate unknowable.

And that's nothing new, because for as much as our technology advances and our knowledge grows, human nature stays pretty much the same. Serial killers — and the widespread fascination with them — have always been there.

Just look back to the 16th century. That's when headlines were filled with the lurid details of the crimes of a serial killer named Christman Genipperteinga, a German man who reportedly killed an unthinkable number of people before he was brought to justice. And by "justice" — "executed in an incredibly horrible way." And here's the thing — just how much of the story is true, well, no one knows. Let's look at the fact and the fiction.

Who was Christman Genipperteinga... supposedly?

The story of Christman Genipperteinga starts in Germany in the 1570s. That, says Executed Today, is when he reportedly set up shop in a cave somewhere in the forests of the Rhineland, which was interestingly the same area that Adolf Hitler would much later set up his own camp to make it clear that he had no intentions of obeying the terms of the Treaty of Versailles. Genipperteinga wasn't a total, full-scale dictator in quite the same way Hitler would be, but he was getting there.

He started out as the head of a gang of robbers, and once he got a taste for killing, he just kept right on doing it. His operation was run out of his Rhineland lair, and their most common victims were German and French travelers who happened to be unfortunate enough to cross paths with them. Those travelers would invariably lose not only their money but their lives, and it was said that even Genipperteinga's partners weren't safe from his murderous rage. He would absolutely turn on his fellow bandits as well, increasing his body count very, very quickly.

What kind of body count was Christman Genipperteinga responsible for?

The story (via The Law Offices of Paul A. Samakow, P.C.) says that Christman Genipperteinga kept a journal for the entirety of the 13 years he spent killing, where he wrote about every death. By the time he was finally captured, there were 964 murders in his log, and he later admitted that he had been so close to his ultimate goal — an even 1,000.

Crime and Culture in Early Modern Germany says that he'd also amassed a huge fortune worth about 70,000 Gulden. That doesn't really mean much to modern eyes, so let's talk about just how much that really is. To put that in perspective, consider this — when Rembrandt bought his Amsterdam house in 1639, he spent about 13,000 Gulden (via vanOsnabrugge). If that's translated into today's American dollars, that's spending the equivalent of around $780,000 (as of 2016). An average laborer earned around 300 Gulden per year, so the amount of stolen goods and coins reportedly found in Genipperteinga's cave would have taken an ordinary person around 233 years to earn.

His story got more and more fantastic with each retelling

Executed Today says that Christman Genipperteinga's story has been embellished considerably over the years... as if a fortune in stolen goods and a ton of dead bodies isn't interesting enough. Sometimes, he's given the powers of a super-human, reportedly able to become invisible at will and commune with a secret cabal of dwarven craftsmen. In other stories, he doesn't just kill his victims, he eats them, too.

Then, there's the story of how he was finally brought to justice.

Genipperteinga apparently got a little lonely during his robbing and killing spree and ended up taking a woman hostage. He held her captive in his cave for an indeterminate amount of time, and however long it was, it was long enough that she had at least several kids with him... that he ate. She eventually escaped and went to the authorities, leading them back to his hideout with the help of a trail of peas.

If that sounds like it's right out of some sort of fairy tale, it absolutely is — it's in Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm's The Robber Bridegroom. It's the story of a woman who leaves a trail of peas as she's walking out to her betrothed's woodland house, where she learns that he's actually one of a group of murderous, cannibalistic robbers.

The end of Christman Genipperteinga

The long arm of the law eventually caught up with Christman Genipperteinga, but his apprehension wasn't exactly the end of the fantastic tales told about him. According to Executed Today, he was condemned to die on June 17, 1581. The method was as terrible as his crimes, and he was sentenced to breaking on the wheel.

That doesn't sound too bad... right? The execution method was as grisly as it was creative, and according to Medievalists, it started with the person being tied to a wagon wheel. The executioner would then break his arms and legs, then those broken limbs would be threaded through the spokes of the wheel, which was then mounted on a pole. It was a very real method of torture and execution, with archaeological evidence suggesting that it wasn't just very sort of routine but also that some victims were wrapped in a shroud to keep their body parts from falling off the wheel. They were generally decapitated at the end of their torture, and that brings us right back to Genipperteinga.

He reportedly lived for nine days while being mounted on the wheel, supposedly kept alive in part by executioners who wanted to make him suffer even more.

Elements of the story show up elsewhere

Executed Today says that even though there are pamphlets and news stories from the time — with one in particular actually dating to the year Christman Genipperteinga was reportedly executed in 1581 — it's not clear if the story is slightly true, if it's incredibly embellished, or if it's complete fiction.

In order for Genipperteinga to have killed 964 people during his reign of terror, he would have needed to average about six people every month... which isn't totally impossible. More unlikely is the idea that he used invisibility to help him meet his quota, but a little bit of embellishment doesn't mean it's all fiction.

But here's the thing — most of the elements of the Genipperteinga tale show up elsewhere, like the trail of peas in the Brothers Grimm story. The idea of a kidnapped bride shows up elsewhere, too — in the story of the robber Lippold. Showcaves says you can still go and visit his cave hideout — appropriately called Lippoldshohle, or Lippold's Cave — along one of the tributaries of the Leine River. According to that story, Lippold held the mayor's daughter hostage until finally he needed to send her into town for some medicine. She promised to tell no living soul about the cave and her captor, so she told the story to a fireplace... and her father just happened to be eavesdropping.

That's the same story that's told about another nearby cave in Germany, called Daneilshohle... and they're all viewed with the same amount of skepticism.

The robber bands of the 16th century

Criminologist Scott Bonn says (via Psychology Today) that part of the reason the public is fascinated with serial killers is the randomness of it all, and there was something going on in the 16th century that put serial killers on everyone's minds — the rise of bandit gangs across Europe.

"Crime and Criminals in Sixteenth-Century Seville" says that throughout the century, cities across Europe were finding a new threat on the rise — robbers, thieves, and bandits were organizing into massive groups, just like the one said to have been run by Christman Genipperteinga. They were a very real and terrifying phenomenon. Martin Stier, for example, was an ex-shepherd who had organized 48 other shepherds into a wandering band of thieves and killers who spent two decades wandering across Germany and the Netherlands. Crime and Culture in Early Modern Germany says there were also groups like the one run by Ulrich Oettinger, who earned the nickname Sew Vile, and Paul Wasansky, who killed and stole from peasants and aristocrats, children and elderly alike.

Genipperteinga may or may not have been real, but the idea of roving bands of killers? That was a very real threat, indeed. Explaining that he — and others like him — were in league with the Devil could have been a way for people to cope with what was going on in their homes and villages, as no ordinary person could have done all those horrible things... right?

Peter Niers, the other serial killer

Part of the reason it's impossible to tell just whether or not there's true elements to the story is that there's a few other serial killers that were running around at the time, including Peter Niers. His story is just as wild and contains some similar elements that many people (boring, cynical people) suggest is proof that you can't believe everything that you hear.

Executed Today says that Niers was definitely real, and that he was definitely a killer. The first mentions of him appear in 1577, when pamphlets telling the story of his capture were published and circulated. Niers first admitted to killing 75 people, but it's also worth mentioning that this confession came under torture. That wasn't the end of him, though — he reportedly broke out of jail and headed back out into the woods.

He wasn't recaptured again until 1581 — the same year Christman Genipperteinga reportedly met his end — and like Genipperteinga, Niers was executed via breaking on the wheel.

As if Niers' story wasn't terrible enough, it was also wildly embellished. Pamphlets from the era suggest that he had learned the art of invisibility, and by 1583, literature claimed that he had made a pact with the devil. In exchange for supernatural powers, Niers killed 544 people in the name of the devil. That included 24 pregnant women, the story went, and it was actually their unborn babies that Niers needed for his black magic rituals.

A Christman Genipperteinga contemporary: Peter Stumpp

There's one more serial killer that was out and about at the same time Christman Genipperteinga was reportedly killing, and it's also worth looking at Peter Stumpp (or Stubbe, or Stumpf) to see how his story was embellished, too.

Executed Today says that Stumpp's story was only preserved in a single contemporary account, which says that he confessed to things like murders, cannibalism, and consorting with a succubus, all done after he made a deal with a demonic power, and was given a belt that allowed him to shapeshift into a wolf. (And again, torture was involved in this confession.) He — along with his mistress and his daughter — met his end on the breaking wheel. Conveniently, the date was Halloween 1589.

Modern Farmer says that there was a lot going on at the time men like Genipperteinga, Niers, and Stumpp were hunting — or reportedly hunting. The era was punctuated by the power struggles of the wealthy, which only made life harder as someone went farther down the food chain. Wolf attacks were a very real fear, and throughout the 16th century, there were scores of werewolf trials. They were pretty much done with ideas similar to witchcraft trials, and the bottom line was that people needed a scapegoat for the horrible things that were happening — and it was easier to understand that a monster was behind them, instead of an ordinary, everyday sort of person.

Scotland had a version, too

Here's another strike against the idea of Christman Genipperteinga being a completely real person who really did kill 964 people — there was another, almost identical version to him that existed in Scotland.

His name, says Historic UK, was Sawney Bean. He pre-dated Genipperteinga by about a century, and it was said that he and his wife first set themselves up in Bennane Cave... then turned to robbing anyone who happened to wander by, while they fed their growing family with the corpses of their victims. The Bean clan spent around 20 years ambushing travelers and butchering them to feed the family that grew to include 14 children... all with a taste for human flesh, and all who bore incestuous babies of their own.

Eventually, they were discovered by Glasgow law enforcement, and in the end, 48 members of the family were arrested and executed. It was estimated that they'd killed — and eaten — around 1,000 people. But here's the thing — there's no real evidence that it happened. According to the BBC, the tale was likely invented in England as a way to spread more rumors about Scotland and the "savages" north of the border.

Let's talk body counts

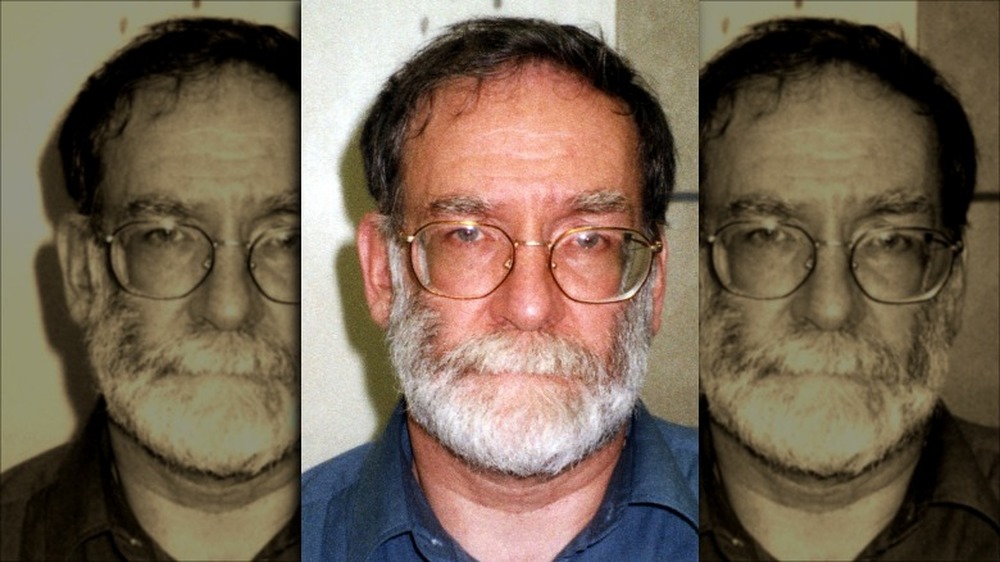

Getting completely accurate body counts for serial killers is tough, because there's usually a discrepancy between what a serial killer confesses to and the number of confirmed victims. So let's talk numbers... and see just how high Christman Genipperteinga's reported 964 kills is in respect to serial killers that existed.

Biography says that British doctor Harold Shipman (pictured) holds the record for being the serial killer with the highest number of confirmed kills. While he was put on trial and convicted of 15 counts of murder, clinical audits found the actual number to be either 236 or 218... possibly more. Hop over to the United States, and you've got Samuel Little, who confessed to 93 murders. According to NPR, by the time of his death in 2020, the FBI had verified 50 of those and were continuing to treat the rest as credible.

There are other high body count serial killers vying for the term of "worst," too. History Collection says Luis Alfredo Garavito Cubillos is a Colombian serial killer with an official number of somewhere between 138 and 192 victims, but the actual number is believed to be somewhere between 300 and 400. Similarly, Rolling Stone says Pedro Lopez was convicted of 110 murders but was likely responsible for more than 300.

All that means that if Christman Genipperteinga really was as bad as history says, he killed the same number of people as four of the world's worst serial killers.

The most prolific German serial killer that did exist

Christman Genipperteinga is called Germany's most prolific serial killer, but what if he didn't exist? Who actually holds that title? It's difficult to say because of the challenges in proving just how many people a serial killer has murdered, but one likely candidate for Germany's most prolific is Karl Grossman.

In 1921, The Washington Times ran an article saying that after 60 years, Grossman's reign of terror was coming to an end — with the help of a hangman's noose. Grossman had been on the radar of law enforcement from the time he was a teen, and when he opened his own butcher shop, it probably should have sent up some red flags.

The True Crime Database says that he did most of his hunting between 1918 and 1921, and that it was "strongly believed" that he used the butcher shop and his hot dog stand to dispose of the bodies of the women he killed. Grossman was finally arrested when his landlady — hearing the screams of the woman he was in the process of killing — alerted police, and they arrived at his apartment in time to catch him in the act of cutting her body into pieces. He confessed to four murders, but many, many more were detailed in his journal.

He was ultimately found guilty of 23 murders and was executed in 1922, but it's believed that his actual number of victims was more than 100 (via Welt).

The most prolific German serial killer that did exist... in modern times

Let's talk about the most prolific German serial killer in modern times, and buckle up, because this is pretty extreme. In 2019, a German nurse named Niels Hoegel was given a life sentence. The crime? The murder of 85 of his patients, although law enforcement added (via RTE) that they were pretty sure the actual total was somewhere in the neighborhood of between 200 and 300.

It's unlikely that a concrete body count will ever be discovered, as many of his victims — who he selected apparently at random — were cremated after their deaths.

According to The New York Times, Hoegel had been shuffled around through the hospital system by administrators who "had grown deeply suspicious about the number of deaths" that happened while he was around. It was later found that he would deliberately overdose patients so he could try to save them, and those who knew him called him "Resuscitation Rambo."

Perhaps they should have been more suspicious — over the course of 15 years and several hospitals, Hoegel killed so many people that he became known as the "most prolific serial killer in the history of peacetime Germany."