The Tragic True Story Of The Fort Pillow Massacre

What exactly is Fort Pillow? A military fort, obviously, but what is it beyond that?

To be entirely honest, most of its history isn't all that interesting. Located in Tennessee and overlooking the Mississippi River, Fort Pillow was constructed by Confederate troops in 1861, taking its name from General Gideon Johnson Pillow, and was intended for use as part of their river defenses. The Confederate army didn't hold onto it for all that long, though: By the next year, Union forces had taken it over and claimed it as their own. The Union army added to it a bit, beefing up the defenses, but, really, for a while, there wasn't a whole lot more that could be said about it. Fort Pillow wasn't even all that tactically important, when all was said and done.

But, obviously, that wasn't the end of the story. Far from it. Despite its unassuming beginning, Fort Pillow would end up meaning a lot, becoming the site of some of the most savage bloodshed in the entirety of the Civil War. After all, the word "massacre" doesn't get tossed around lightly. The description was well-earned in all the worst and most tragic ways: The three-year anniversary of the start of the Civil War really was something.

The Battle of Fort Pillow

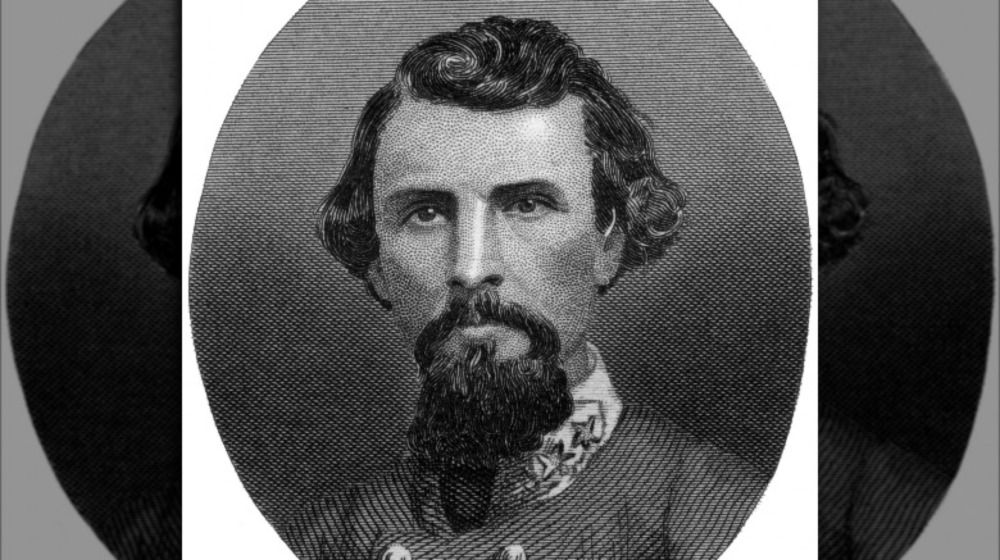

This entire story starts with a battle. (Of course; it was the Civil War.) In April 1864, Confederate Major General Nathan Bedford Forrest (pictured above) turned his attention from the destruction of Union supply lines to Fort Pillow (via History). On the morning of April 12, Forrest turned his cavalry toward the fort, manned at the time by about 600 Union soldiers. According to the account of Lieutenant Mack Leaming, a Union soldier present at the battle, the Confederate soldiers fired on the fort for hours, making a number of attempts at breaching its walls. Those attempts weren't successful, but the Union soldiers did lose their commanding officer in the process.

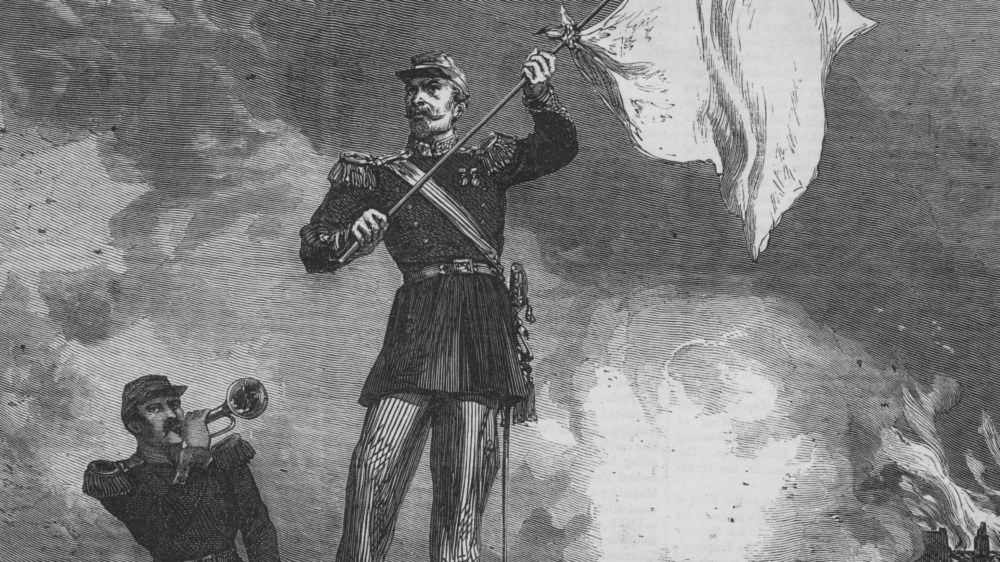

Forrest wasn't concerned, though. According to his own account, he had no doubt he could successfully take the fort and, at around 3:30 PM, waved a flag of truce. He demanded the unconditional surrender of the fort defenders and, through the course of a few exchanged messages (per Leaming), expected a swift reply, which would give the Union no chance to wait for reinforcements.

Long story short: the Union refused to surrender. What they didn't know, though, was that Forrest had used the truce to move his troops into a more advantageous position (one he'd been trying to gain during the earlier fighting). So when the firing started up again, the Confederate troops were able to storm the fort in almost no time at all, and the Union soldiers threw down their arms in surrender.

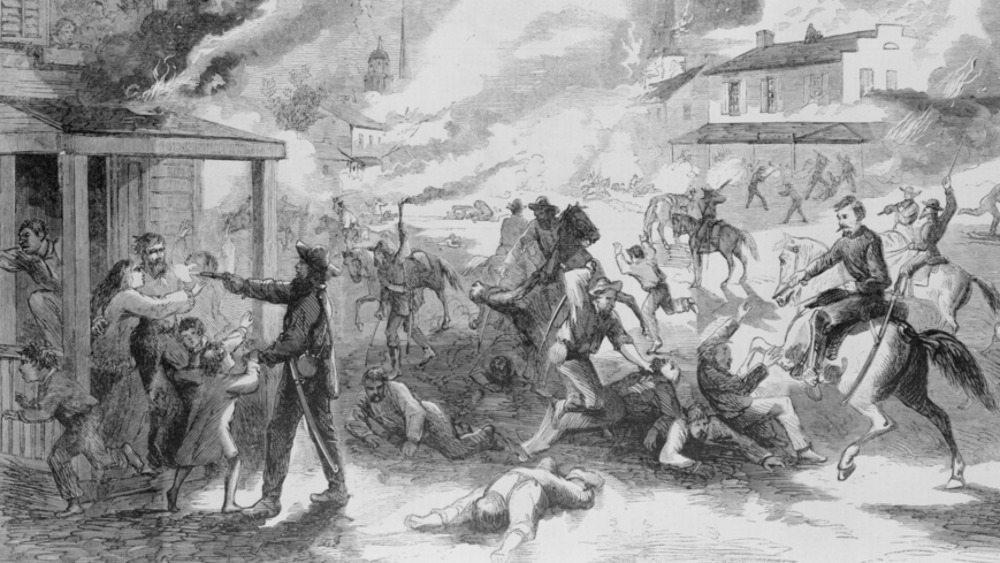

An indiscriminate massacre

What followed after the battle is, honestly, almost difficult to describe. Union troops had thrown down their arms and surrendered to their enemies, but the death and destruction had hardly even begun. Lieutenant Mack Leaming said that the Union troops were shot down left and right, seemingly indiscriminately, though the Report of the Committee on the Conduct of War (via The New York Times) had a lot more to say.

The slaughter went way past just soldiers. Civilians — men, women, and even children — weren't spared from the terror. They were shot, just the same as the soldiers, and some of them were murdered with sabers. Children, sometimes less than ten years old, were forced to stand and look their killers in the eyes as they were shot. One child might have seemed nearly safe, picked up by a soldier and placed behind them on a horse, only for another soldier to order that the child be set down and shot on the spot.

The order was followed.

Given all that, it's honestly not even that surprising to know that the wounded weren't spared, either. Injured soldiers were forced to stand, even if they could barely do so, only to be shot. Men in hospitals were shot where they lay, even as they hoped for mercy, according to another eyewitness account (also via The New York Times).

Hours of violence

Lieutenant Leaming wrote about the details of the massacre decades after it happened, mentioning that the violence raged for hours and hours. He'd been wounded shortly after the Confederate soldiers first stormed the fort but wasn't killed in the ensuing bloodshed. Instead, he got to have a front seat to it. Resistance by the Union troops had already stopped, but he could periodically hear shots being fired all through the night. It was well after any pretense of battle had ended, but the calls for blood weren't anywhere near to ending. Another eyewitness account lines up with that, mentioning that the gunshots (and the cheering that came with them) were still audible at 2:00 AM.

Gunshots weren't the end of it, though, and Leaming recalled that, come the next morning, he heard that all the buildings were to be burned. The Confederate troops followed through on that — Leaming himself was inside one of those burning buildings before he was helped out. Not everyone was quite so lucky. The Report of the Committee on the Conduct of War weighs in on this, too, mentioning how the tents and buildings housing the wounded were being set aflame since the night before. More than a few people died because they couldn't escape or weren't lucky enough to be helped, and others suffered even worse fates: One man was nailed to the floor of a tent and another to the side of a building, trapped as they burned.

Union reports on the Fort Pillow Massacre

Unsurprisingly, both sides had a lot to say about what had happened at Fort Pillow. When it came to the Union's version, the Confederate Army was, as you might expect, painted as the villain.

They had pretty good reasons for it, though. According to History, the Union pointed out that their men had already surrendered. The Confederates had no reason at all to keep fighting, but they did anyway, slaughtering those who had already laid down their arms. They heard the cries for mercy, knew that the Union soldiers should've been taken as prisoners of war (via History), but paid them no mind. And when you look at the casualties, the Union version of the story seems to ring true: Hundreds of Union troops were killed, while the Confederate army only lost a few dozen.

The Northern newspapers really got into it, too, reporting on the story of cold-hearted and bloodthirsty savages slaughtering the brave heroes of the Union. But the most influential thing that might've come from the news reports? The name "The Fort Pillow Massacre." A paper by Colin Strickland and Timothy Huebner explains that Northern newspapers dubbed it as such, and, well, the name has stuck.

What did the Confederates say about Fort Pillow?

Of course, the Confederates had a very different take on the events at Fort Pillow. As History tells it, the Confederates claimed that there wasn't actually any surrender. The fort's defenders kept on fighting and resisting, so what else could they do but try to defend themselves? There was none of this "slaughter" or "massacre" nonsense, just self-defense. It could've also been explained as just the heat of conflict and battle, as mentioned by the Report of the Committee on the Conduct of War (even if that same report basically shot down that defense).

When General Forrest came under fire, accused of being, essentially, the mastermind behind everything who told his troops to gun people down, his defenders argued that there was no actual proof of him giving such a command. And then when Northern newspapers started printing their versions of the event, Southern publications responded by claiming that everything coming from those Northern newspapers was just a lie.

And as for Forrest? There are arguments to be made as to whether the massacre happened with his blessing or if he'd lost control over the situation, but the man himself was strangely quiet about it. His own report makes basically no reference to the hours of bloodshed. He mentions some death and the burning of the buildings but little else. Reading his report on its own would make Fort Pillow seem like a relatively casual walk in the park.

There was technically no surrender (but really, there was)

There are two different sides to the story of what happened at Fort Pillow, and, naturally, the truth is a little bit in between. Leaming was a Union soldier who wrote about the incident years later, and in his recounting of the whole thing, he admits that, yes, it's true, there wasn't a formal surrender. Forrest did call for the Union to surrender the fort: If they did, then the men would all be treated as prisoners of war (via History). And the Union did officially reject that offer, leading the Confederate Army to storm the fort. That much is true.

But here's the thing: Even if there wasn't an official surrender, there was still an effective one. The Union soldiers had dropped their arms and stopped resisting entirely. They'd all been overpowered and captured; that was effectively the same as surrendering. And then there are accounts of an even clearer surrender by Union troops. Wounded men lay in the hospital and had torn off any piece of white cloth they could, holding it over their heads in a sign of obvious surrender (via The New York Times). But that didn't matter. They were killed where they lay.

In the end, sure, there wasn't a formal surrender, but history sees the Confederacy as in the wrong. And the Report of the Committee on the Conduct of War says the same thing. If nothing else, the violence was excessive and unwarranted.

The Fort Pillow Massacre didn't seem all that indiscriminate

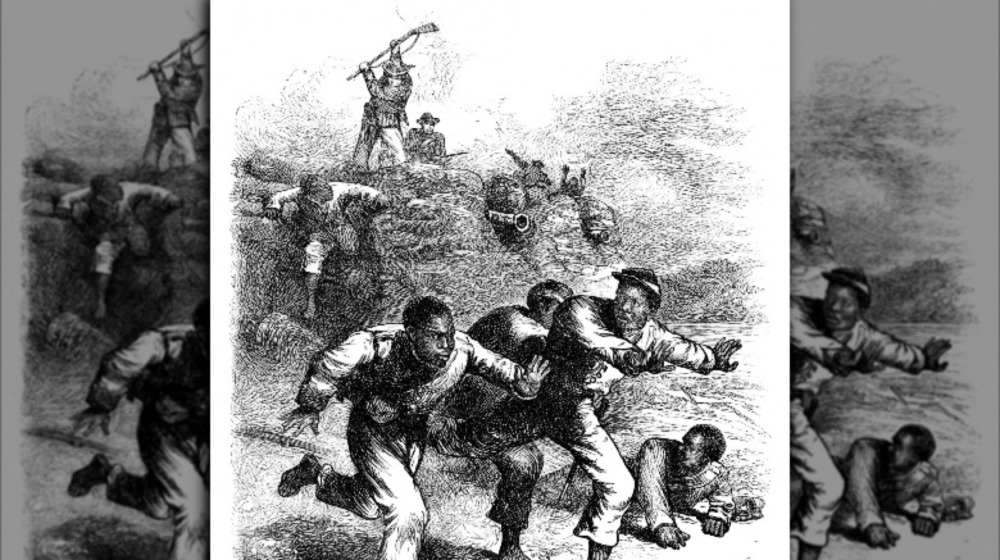

The Fort Pillow Massacre isn't infamous just for being a massacre. It's infamous (and controversial) for a lot more than that — namely, what happened to the Black troops.

There were about 600 Union troops defending Fort Pillow. Almost half of their number were African American (via History). And when you look at the stats regarding the casualties, there's a definite trend: African American troops suffered a death rate of about 64 percent, whereas the fatality rate of their white counterparts was around half of that. That doesn't seem particularly coincidental.

Leaming's story seems to support that. He watched as soldiers jumped into the river to flee, Confederate bullets hitting the water around their heads. Then, as he was pulled from a burning building along with other wounded troops, a Confederate soldier walked by and noticed a Black soldier lying on the ground, shooting him through the head without preamble. That same soldier saw another Black soldier nearby. The man pleaded for his life, begging for mercy and saying that he was forced to fight. None of that meant anything, and he was killed, too.

Forrest's exact part in the massacre is up for debate, but he wrote in a dispatch that he "hoped that these facts will demonstrate to the northern people that negro soldiers [...] can not cope with Southerners." If nothing else, he didn't seem to have a lot of regrets.

There seemed to be two targets during the Fort Pillow Massacre

The particularly controversial part of this story tends to center around the slaughter of Black troops by Confederate soldiers, but they didn't actually seem to be the only targets that the Confederate army was gunning for. After all, Fort Pillow was originally built in Tennessee as a Confederate stronghold, not a Union one (via History).

With that in mind, they didn't really look all that kindly on troops from Tennessee who chose to fight on the side of the Union. As American Battlefield Trust puts it, they saw those men as traitors and turncoats — people who deserved punishment just as much as the African Americans they were slaughtering. And that's not an exaggeration: It's exactly what the soldiers said themselves. The Report of the Committee on the Conduct of War included testimony from a Confederate soldier who explained that they had no intentions of treating these "home-made Yankees" any differently than African Americans.

Leaming's report, again, seems to confirm the same thing. Major William Bradford, the fort's de-facto leader before the Confederates stormed in, was from Tennessee himself and supposedly had a lot of enemies in Forrest's regiment, specifically because of where he was born. Being from Tennessee and fighting for the Union was treachery worthy of death in the eyes of the Confederates. Indeed, Bradford was marched off into the woods and executed.

The Confederate soldiers seemed to know what they were doing

The Report of the Committee on the Conduct of War makes its findings very clear: The brutalities committed by the Confederate army during the Fort Pillow Massacre weren't just the result of self-defense or the heat of battle. It was a deliberate policy, slaughtering troops and denying Black soldiers in particular any of the rights of being prisoners of war.

The things the Confederates said seem to bear that out — cries to kill Black soldiers specifically could be heard everywhere, and then there were the cries of "No quarter!" They didn't intend to take prisoners. They intended to win the battle by completely decimating the Union forces. "Slaughter" sounds like it was the name of the game.

Then there's the matter of the wounds themselves. The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History explains that witnesses saw that most of the wounds were centered around the torso and head. Most battlefield injuries were to the limbs, so these were intentional killing shots, not just desperate stabs at survival.

And, of course, there's General Forrest to take into account, too. An account from a Confederate soldier says that he "ordered them shot down like dogs" (via History), and another account states that killing injured Black troops and the White officers who served with them was official policy (via History News Network). Sounds pretty implicating.

The aftermath of the Fort Pillow Massacre

The Fort Pillow Massacre had some pretty long-lasting effects, and rightly so. As History News Network says, the injustice there served as a rallying point for Black troops in the Union army for the rest of the Civil War. "Remember Fort Pillow!" ended up becoming their battle cry until the war ended. The Union at large was infuriated by what happened, too, refusing to take part in prisoner exchanges for the rest of the war (via History), and the Report of the Committee on the Conduct of War didn't take kindly to what happened. The report's exact words call it a "scene of cruelty and murder without parallel in civilized warfare" and akin to "the worst atrocities ever committed by savages."

Yeah, it really wasn't pretty. At all.

But here's the part that's ridiculous: Forrest's reputation was barely even tarnished by this event — not even years later. Even well into the 21st century, his name is on schools and public buildings. There have been statues and memorials and monuments (like the one shown above) dedicated to him despite what he did, and those monuments tout his military genius as a great defender. It's a part of a much bigger problem surrounding the legacy of the Civil War — one that deserves a long conversation of its own.

The link between the Fort Pillow Massacre and the KKK

Correlation doesn't equal causation — that good old bit of wisdom. Circumstantial evidence doesn't necessarily equate to proof. That sort of thing. And so, yes, there are those accounts that say the Confederate soldiers only killed as many as they did out of self-defense or that Forrest himself had no direct involvement in the slaughter other than just losing control of his men (via History). But when you look into the time after the Fort Pillow Massacre, it's easy to wonder a bit.

The Union victory in the Civil War brought with it Reconstruction and the inclusion of more African-American citizens into public life. Of course, not everyone was pleased with that, and the Ku Klux Klan formed. As History explains, the group came together as a means of protesting Reconstruction and the Republican Party's intentions of bringing some level of equality to Black Americans. White Supremacists had a vehicle through which they could try to re-establish the old ways.

So, where does this intersect with the Fort Pillow Massacre? The answer is: Nathan Bedford Forrest. The Confederate general wasn't just part of the KKK but also its first leader, being named the first "grand wizard" of the group when it initially formed in 1866 (via History). The group was dissolved a few years later, and Forrest denied any involvement when questioned by a Joint Congressional Committee. Given the reputation of the KKK, it's certainly not a good look.