US Presidents Who Suffered The Most Tragic Deaths

The social class structure has been a thing since humankind realized they can hit other humans and steal their stuff — meaning they'll have all the stuff — and from there, it's only gotten more complicated. (And occasionally, there's even less hitting.)

Today, there's a very deep class divide all over the world, and when it comes to America, the tippy-tippy-top is the president of the U.S. We tend to think of them as having the best of the best, from top-notch security to all the best food, and the biggest, comfiest sofas. (Probably.) But presidents are still susceptible to all the functions that make us human, like aging and ultimately, death.

Death is, as they say, the great equalizer. Every single person — no matter how much stuff they have — has to face the end by themselves, and a lot of the time, it's pretty terrible. It's painful and messy and oftentimes brutal, and for these presidents? It was definitely all that, and sometimes, even more. It turns out that some of the men who shaped the country from the very top were doing while facing their own secret struggles... and confronting their own mortality.

George Washington's awful bloodletting

The country's first president was only about two and a half years into his post-Founding Fathers' retirement when he suddenly took ill. From start to finish, the National Constitution Center says it was about 21 hours of illness, and — by late afternoon — George Washington knew that the end was near, so he made sure his affairs were in order. In the centuries since, medical professionals have debated exactly what killed the first president, and guesses range from diphtheria to an inflammation of the larynx, which would have caused the difficulties breathing that he experienced. One of the popular contenders now is acute bacterial epiglottitis... and here's what happened.

Washington had been out riding on a cold, damp day, and opted to stay in his wet clothes so he wasn't late for dinner. The next day, he sent for the doctors — and according to the University of Michigan's Dr. Howard Markel (via PBS), if the illness didn't get him, the treatment did. That included bloodletting, and over the course of 12 hours, about 40 percent of Washington's blood was drained. In an attempt to try to open his airway, Spanish fly was applied in an awful treatment that causes blisters to form on the inside of his throat. There was also the administration of enemas, and he was given various concoctions to gargle with: including one mix of butter, vinegar, and molasses.

Nothing worked, and he thanked each doctor for their attempts at saving his life.

Thomas Jefferson struggled with a laundry list of ailments

Historians at Monticello say that it's unclear just what killed Thomas Jefferson at the age of 83, but they say that in the years leading up to his death, he suffered from a massive list of health problems — which we know in part thanks to his extensive writings. His health started to go downhill after 1818, and it started when — already suffering from rheumatism — he spent some time at the mineral baths of Virginia's Warm Springs. It was there that he developed a "boil on his 'seat'," and most surprisingly, in spite of the deep infection, he continued to take his daily horseback rides.

And this was likely a case of the treatment being worse than the illness. Jefferson's infection was treated with ointments containing high amounts of mercury and sulfur, which did help get rid of the infection, but caused all kinds of other problems, like the "chronic bowel problems" he suffered from for years. Then, in 1825, he struggled with a bladder issue that necessitated the use of what was basically a catheter. This was before sterilization, though, and the bacterial damage that spread to his kidney sent him into a painful decline.

Bedridden by June 1826, he was also suffering from pneumonia and what doctors now believe was prostatic cancer. He died on July 4, and as he was mostly in a semi-conscious stupor, his last words were unclear.

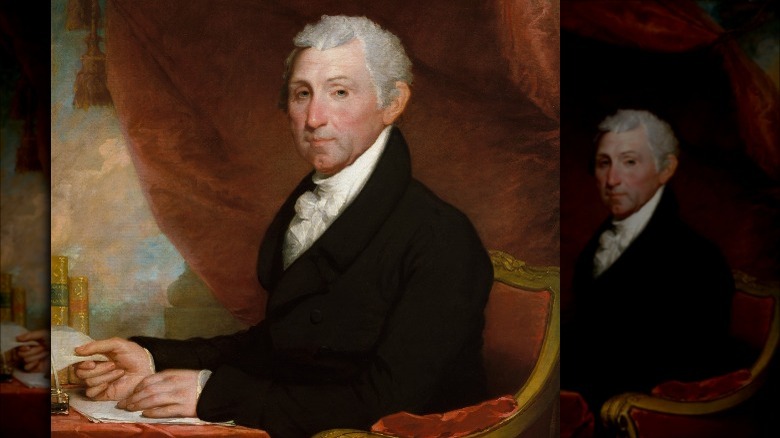

James Monroe's longtime health struggles

When it comes to creating the country we know today, James Monroe was a pretty big deal — he was, after all, the one who negotiated for the Louisiana Purchase. He became president during the so-called Era of Good Feelings, says ThoughtCo., and seriously... can we get this guy back?

His achievements are even more impressive when it's taken into account that he was suffering from serious illnesses during his entire presidency. According to The Philadelphia Inquirer, it all went back to 1785, when he caught malaria on a trip along the Mississippi. For the rest of his life, he suffered fairly regular recurrences that left him bedridden, feverish, and coughing up quantities of blood. By 1831 — six years after he left office — his cough and breathing difficulties were getting progressively worse.

He wasn't given a concrete diagnosis at the time, but medical experts today are pretty sure he was also suffering from tuberculosis. It's likely that it was always present, and that the stress of his job essentially kick-started latent TB into an active infection. When he died on July 4, 1831, the official cause was heart failure. Now, it's believed that tuberculosis was the underlying cause, and according to Denver Health, we could have cured him today.

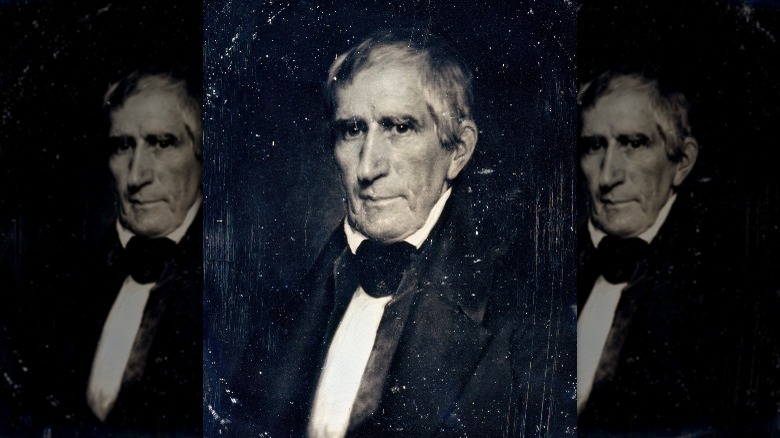

The cruel joke at the expense of William Henry Harrison

Anyone who remembers William Henry Harrison remembers him for one reason, and one reason only: He died just a month into his term (on April 14, 1841), after contracting pneumonia during his long-winded, two-hour inauguration speech. According to History, historians have thought for a long, long time that it was that speech — on a wet, cold winter day — that led to his death. That's the oft-told story, and it's one that's turned him into something of a joke. Modern research, however, suggests that's both completely unfair and not what happened at all.

In 2014, University of Maryland researchers Jane McHugh and Dr. Philip A. Mackowiak re-opened the case and noticed something immediately obvious: Harrison didn't get sick until about three weeks after his speech. The symptoms he experienced the worst weren't lung-related, either — they were gastrointestinal. The verdict? Enteric fever.

At the time, Washington, D.C. was missing something pretty important: a sewage system. Water flow meant that most of the capital's excrement ended up in a marshy area just seven blocks away from the White House's water supply, and according to The New York Times, Harrison had chronic indigestion, which would have made him more susceptible to the effects of the fecal bacteria in the water supply — a much bigger concern than not wearing his mittens.

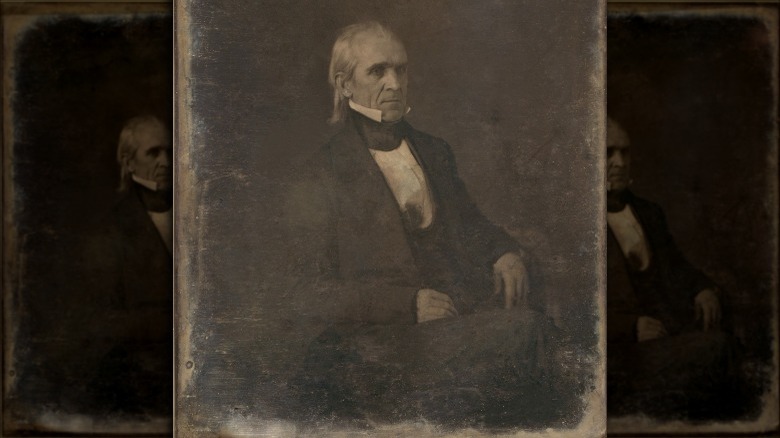

James Polk didn't get to enjoy his retirement

Everyone hopes to be able to enjoy their retirement in comfort (and preferably on a beach somewhere), but according to the President James K. Polk Home & Museum, Polk had the shortest retirement period of any U.S. president. After leaving office, he and his wife went to New Orleans, then headed back up to their Nashville home via the Mississippi River. Along the way, he made reference to the cholera outbreaks they say, and for his last ever diary entry even wrote, "During the prevalence of cholera I deem it prudent to remain as much as possible at my own house."

Two weeks later, he died of cholera.

According to The Philadelphia Inquirer, Polk had gotten sick in New Orleans — and cholera isn't pleasant. It's characterized by extreme exhaustion, acute abdominal pain, vomiting, severe diarrhea, dizziness, and muscle cramps. With today's medical knowledge it's likely that he would have survived, but at the time, treatments like bleeding and laxatives only added to dehydration.

Polk died on June 15, 1849, just about three months after leaving Washington, D.C. In hopes of containing the cholera outbreak, he was first buried in a mass grave, then reinterred at his final resting place.

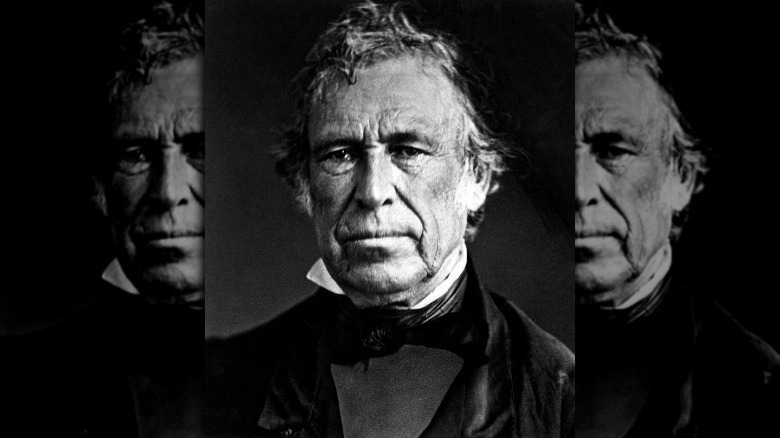

Zachary Taylor's cherries

Zachary Taylor made some serious statements as the 12th president — including telling the southern states who were threatening to secede over his anti-slavery position that if they did, anyone "taken in rebellion against the Union he would hang." That conversation actually happened in February 1850, says The White House, and on July 9, he was dead — after just five days of a sudden and brutal illness.

On July 4, Taylor laid the cornerstone for the Washington Monument, ate a lot of fruit, drank some milk, and hours later, he was crippled with agonizing cramps, a fever, and severe gastrointestinal distress. He was treated with then-normal "remedies" like opium, mercury chloride, and quinine, but the symptoms never disappeared and he died shortly after (via Hektoen International).

Even though it was often repeated that he'd died from a reaction caused by eating cherries and drinking milk, History says it's more complicated. The official cause was cholera, but not everyone's happy with that. It's even been suggested that his anti-slavery, anti-secessionism stance got him assassinated. How true that might be isn't clear: when his remains were reexamined in 2014, the chief medical examiner of Kentucky announced (via Courier Journal) that the levels of arsenic in his system were completely normal. Also? The autopsy still hadn't been able to prove what caused the sudden, excruciating illness that killed him. They do add, though, that it's entirely possible that the medicine he was given was more lethal than his actual illness.

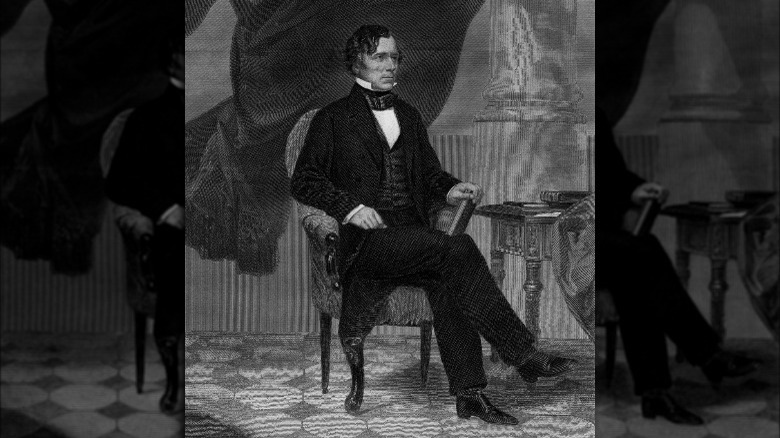

The heartbreak of Franklin Pierce

Mental Floss calls Franklin Pierce "America's most obscure president," and that's pretty harsh. They also say that it was his heavy drinking habit that contributed to his 1869 death, and that's likely: The New England Historical Society says the official cause was cirrhosis of the liver. Pierce didn't drink because he was some kind of party animal, though — he drank to drown the sorrows of his life... and there were a lot of them.

By the time Pierce ran for president, he and his wife had already buried two of their children. Left to them was their 11-year-old son, Benny, who Boston describes as "intellectual, kind, and agreeable." He was "almost idolized" by his father, and it was on January 6, 1853, that he died. Pierce, wife Jane, and son Benny were taking a train from Massachusetts to New Hampshire when there was a derailment. Benny was the only casualty: he was nearly decapitated, which Pierce reportedly didn't realize until he picked up his beloved, final son.

Pierce never recovered. When he was sworn in as president, he refused to take the oath on the Bible, as he was convinced he had been damned for going against his wife's wishes and continuing his political career. His presidency destroyed his reputation, those who knew him turned on him, he buried his wife and one remaining friend — writer Nathaniel Hawthorne — and sank deeper into the alcoholism that eventually killed him.

Abraham Lincoln's assassination

The assassination of President Abraham Lincoln is one of the most oft-told stories in American history, and most have heard — repeatedly — about how he was shot while attending a play at Ford's Theatre. So, let's talk about some of the most obscure details of this tragic assassination.

Why didn't Lincoln have any security at the theatre? According to the Smithsonian, he did: a man named John Parker. Parker was Lincoln's only protection that night, and he was one of Washington, D.C.'s first police officers. Bizarrely, his career is something out of a bad '90s sitcom, filled with reprimands for being drunk on duty, visiting local brothels, and sleeping on streetcars while he was supposed to be on patrol.

On the night Lincoln was shot, he had been three hours late for his shift in guarding the president, and during the intermission, he decided to head to the next-door Star Saloon — where Booth had been drinking up his courage earlier — for a few beverages. He was still there when the shooting took place, and he was blamed — by other officers and by Mary Todd Lincoln — for being the reason Lincoln died that night.

Immediately after the shooting, Lincoln was taken to the nearby Petersen boarding house — where more than 40 people came and went from his room as he lay dying. Among those at his side — for a time — was Andrew Johnson, who left when it became clear he needed to get ready for his own inevitable inauguration.

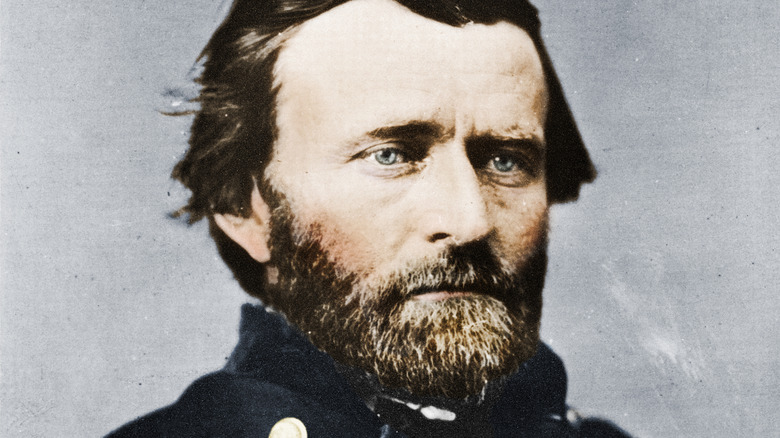

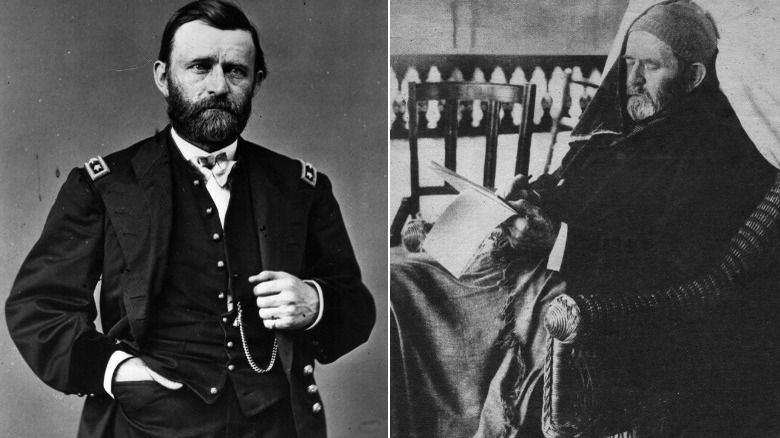

The failures of Ulysses S. Grant

While Ulysses S. Grant might be remembered as one of the nation's most famous generals, the story of his death is nothing short of heartbreaking. It started in 1884: That, says History, is when Grant realized that a shady investment partner had convinced him to invest his entire life savings into a pyramid scheme, which had collapsed and left him penniless. A few months later, a visit to the doctor confirmed that his chronic throat pain was advanced throat and tongue cancer.

Confronted with his imminent death, Grant realized that his previous financial miscalculation was going to leave his wife and family destitute. So, he threw everything into one last-ditch effort to secure their future: With the help of his old friend Mark Twain, he signed a contract to write his memoirs for Twain's new publishing house. What followed was a race against time — and his advancing cancer. Fueled by pure grit, determination, and (in the end) morphine and topical cocaine to dull the pain, Grant wrote as much as 10,000 words per day, first in his own hand, and later, whispered to a stenographer. Within less than a year, he finished his 366,000-word memoir, and when Twain brought news that he'd already pre-sold 100,000 copies, Grant knew he'd provided for his family.

He died on July 23, 1885, seven days after he finished writing. When the book was published, Julia Grant received royalties that today would equal around $12 million.

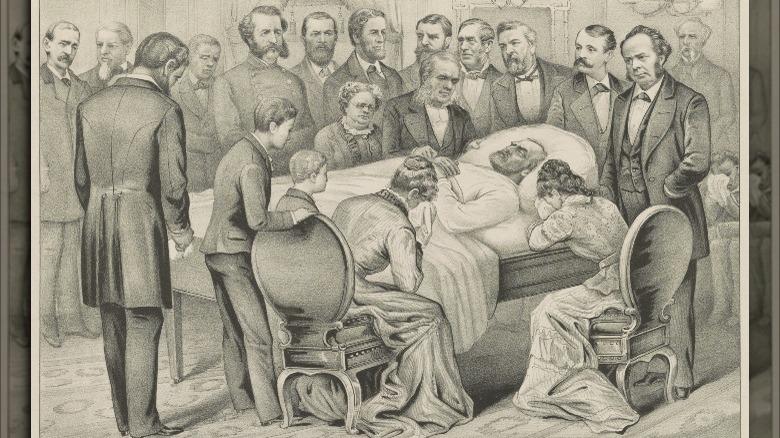

James Garfield, a gunman, and some dirty doctors

When Charles Guiteau shot President James Garfield at the Baltimore and Potomac train station, the first shot nicked his arm, the second embedded itself in his abdomen, and he remained completely conscious — and shocked — throughout the entire episode. The president — widely regarded as good-natured and charming, PBS says, was then subjected to some of the most brutal treatment in the medical history of the White House — and if he hadn't been, there's a chance he might have lived.

The shooting happened in 1881, and it was a time when things like the germ theory and sterilization hadn't gone mainstream yet. And that's important to keep in mind, because it puts things in perspective.

Garfield was taken to the White House, where doctors became determined to remove the bullet from his abdomen. The working theory was that if it were left in, it would cause something called "morbid poisoning," and essentially cause inevitable organ failure. Not only did doctors not wash their hands before they went poking around inside his guts, the 3-inch wound left by the bullet was ultimately opened to 20 inches, and — unsurprisingly — infection and sepsis set in. Garfield survived for 80 days, during which he lost around 80 pounds. His last words were, "This pain, this pain!" and the official cause of death was massive hemorrhage, blood poisoning, and a heart attack.

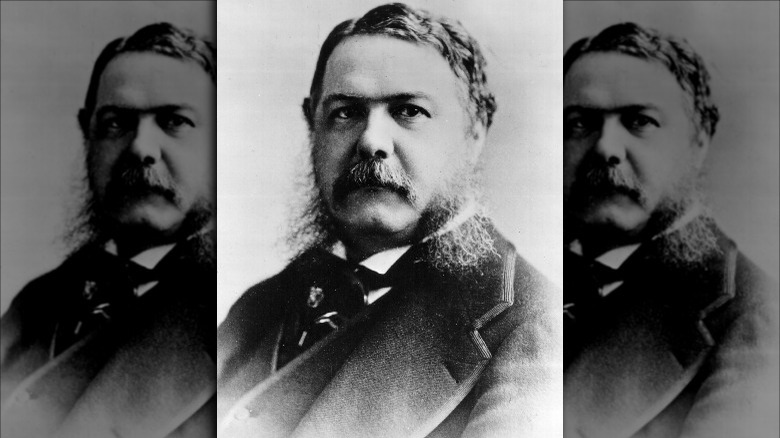

Chester A. Arthur's slow death

Chester A. Arthur was inaugurated after the assassination of James Garfield, in 1881. He served as president for only a few short years and didn't get the nomination of his party in 1884, and for a long time, popular history suggested it was because he just didn't get along with the other members. Bit according to documents discovered by University of Wisconsin history professor Dr. Thomas C. Reeves (via The New York Times), he didn't run for president because he knew that he was dying.

Less than a year into his time as president, Arthur was diagnosed with something called Bright's disease. It's a kidney disease that Healthline says is now called glomerulonephritis, and it basically means that the blood vessels in the kidneys — which are crucial to the process of filtering impurities and fluids from the bloodstream — are damaged. Once that happens, the kidneys stop working and kidney failure is inevitable.

Arthur's condition remained secret for so long because most of his papers were burned after his death, but the discovery of this surviving treasure trove of historical information revealed the fact that only a few people knew Arthur was dying. Even as he presided over boisterous state dinners, a cousin wrote that he was "sick in body and soul," and he ultimately died on November 18, 1886 — about a year after his presidency ended. Today, glomerulonephritis is treatable if diagnosed early.

William McKinley's assassination... that should have failed

William McKinley was at Buffalo's Pan-American Exposition on September 6, 1901, when he decided to ignore the advice of his advisors and hold a meet-and-greet handshake session with members of the public. That, says the National Constitution Center, is when he was shot by Leon Czolgosz. (Unrepentant, Czolgosz was executed via the electric chair the following month, says the Miller Center.)

Initially, it was believed McKinley was going to survive — doctors were so confident that his vice president, Theodore Roosevelt, didn't return and instead, continued on with his family vacation. One bullet was deflected by the buttons on his suit and the other punctured his stomach and lodged in his abdomen. The emergency surgery that was performed was, says History successful, and just a few days later, the president was even requesting copies of the newspaper be brought to him in bed.

On September 13, though, he took a turn for the worse. The unsanitary conditions in which he was operated on — which were still pretty common for the time — had led to gangrene forming on his stomach. That, in turn, led to a fatal case of blood poisoning, and he died early on the morning of the 14th. Countries across the globe declared official mourning periods to grieve the beloved president.

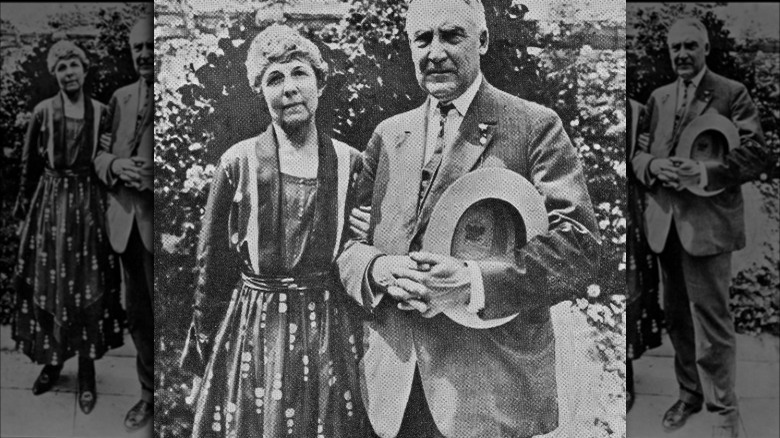

Warren G. Harding's potentially scandalous demise

Warren G. Harding might not be a household name anymore, but when he died suddenly in 1923 — and became the 6th president to die in office — he was absolutely a topic of household conversation. According to PBS, Harding was on a 15,000-mile speaking tour when he started feeling pretty funky. Assuming that the indigestion, fever, and difficulty breathing — coupled with chronic signs of heart disease — was just stress from the trip, he kept going. Until, that is, the evening of August 2. That's when he quite literally took his last breath and collapsed.

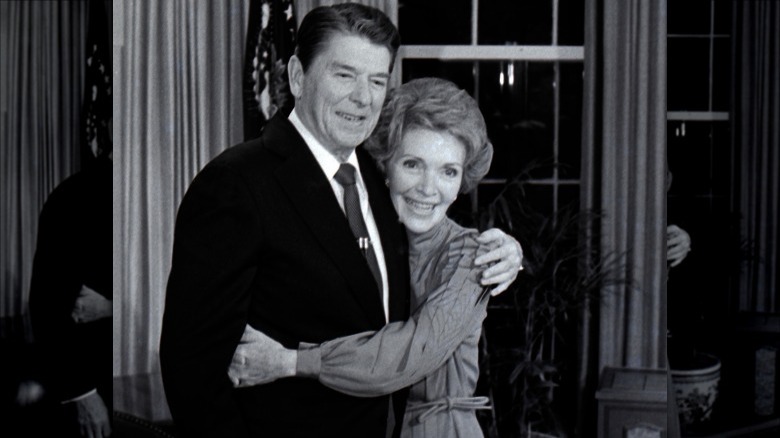

What followed was a lot of finger-pointing from the public, who accused Harding's doctors of everything from malpractice to incompetence. Then, in 1930, a former Harding official published a book that suggested his long-suffering wife, Florence (pictured with him), had finally gotten so sick of his numerous affairs that she'd decided to put an end to it once and for all — the lethal way.

Florence's case wasn't helped much by the fact that she ordered her husband embalmed immediately, before any autopsy could be performed. While the National Constitution Center says that rumors he'd been poisoned were debunked (particularly by the book's ghostwriter), more and more scandals kept on coming. It even spawned rumors that he'd had at least one illegitimate child while in the White House, but bottom line? It was a heart attack — no less tragic, simply less scandalous.

FDR's secret struggle against death

It's commonly said that Franklin Delano Roosevelt hid the fact that he was crippled by polio from the public, but that's not entirely true: major news outlets regularly mentioned his wheelchair, and he very publicly upgraded the White House to make it more accessible. He did, however, hide other health problems that included things like hypertension and a severe iron deficiency (via Hektoen International).

In 1944, he was looking at running for his fourth term, and according to The Washington Post, his health was so bad at that point that his doctors warned him not to do it. He suffered from fatigue and exhaustion, and a listen to his lungs revealed to doctors at Walter Reed that fluid was building up there: he was very slowly drowning.

FDR, historians say, knew that he was dying. But he also knew that World War II was nearing the end as well, and he firmly believed he needed to be there for it. (Still, party members decided he needed a VP capable of taking over for him when the inevitable happened, and replaced his former running mate with Missouri senator Harry S. Truman.) He easily won another term, but — while putting on the happy and optimistic face in public — he struggled with severe chest pains, high blood pressure, and illnesses like bronchitis. On April 12, 1945, he complained of a massive headache, and was dead two hours later.

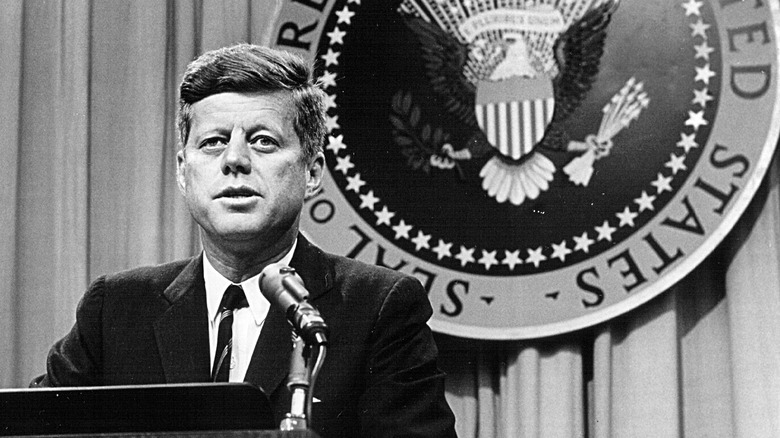

The continued mystery of JFK's assasination

There are few moments in American history that are as famous as the assassination of John F. Kennedy. Everyone has seen the footage, and here's a brief recap (via the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum): JFK was gearing up for announcing a run for a second term as president, and as part of a series of campaign engagements, he was in Dallas, Texas on November 22, 1963. Gunfire erupted over his motorcade at 12:30 pm, and he was pronounced dead half an hour later. At 2:38, his vice-president Lyndon B. Johnson was sworn in as the new president. Lee Harvey Oswald had already been arrested.

More than half a million people made the trip to Washington, D.C. to pay their respects in person, and of all the photos of his death, perhaps the most moving is the one that captures his son, standing by the side of the road, giving his father one final salute. That son was John F. Kennedy Jr., and it was his birthday that day.

The assassination also gave rise to an almost insane number of conspiracy theories (via The Conversation), and while nothing's been proved on the alien front yet, here's a weird bit of trivia: the infamous car that JFK was killed in was only briefly impounded for evidence-gathering. Then, the Lincoln Continental was returned to active duty at the White House, where it was used by Johnson, Nixon, Ford, and Carter. It's now at the Henry Ford Museum.

LBJ faced his conflicted legacy

It was Lyndon B. Johnson who took over after the assassination of JFK, and Johnson left the presidential office behind in 1968. From there, he did what he loved best — tending the animals on his Texas ranch — and he died on January 22, 1973 (via History).

In the years after the presidency, Johnson became increasingly despondent that the good things he'd done — like overseeing the Civil Rights Act, the Voting Rights Act, and the Fair Housing Act — were overshadowed by the giant stain that was Vietnam. According to PBS, his depression was deep: so deep that he'd sometimes sit and listen to "Bridge Over Troubled Water" on repeat. With three heart attacks already on his medical record and regular heart and chest pains, it's not entirely surprising that his doctors had warned him way back in 1955 that if he continued to smoke, he would die early. Still, after 1968, he went right back into the chain-smoking habit — claiming it was better than facing his nerves and depression nicotine-free.

LBJ often said that he knew he was going to die young, saying (via The Atlantic), "My daddy was only 62 when he died, and I figured that with my history of heart trouble..." He'd guessed he would die at the age of 64, and he did — old and aged well before he was actually old.

Ronald Reagan's decade-long battle with Alzheimer's

It was 1994 when Nancy and Ronald Reagan went to the Mayo Clinic. He had been getting increasingly forgetful, and they already knew that something was terribly wrong. The diagnosis was Alzheimer's, and on November 5 of that year, Reagan penned what would be his last open letter to the country. In it, he wrote, "... we feel it is important to share [the diagnosis] with you. In opening our hearts, we hope this might promote a greater awareness of this condition. ... as Alzheimer's disease progresses, the family often bears a heavy burden. I only wish there was some way I could spare Nancy from this painful experience. When the time comes, I am confident that with your help she will face it with faith and courage."

Ronald Reagan died on June 5, 2004, after what Nancy called "a long goodbye." A family friend told Newsweek, "We all said goodbye 10 years ago when he still knew who some of us were. She took the responsibility in caring for what was left."

By the time he broke his hip in a fall in 2001, they gave him three months to live. He would, of course, live another three years, but family insiders revealed that while they were prepared for him to go, it was when the burial was over that the grief set in for Nancy: "That was really the beginning of her pain. She's in that house all by herself."

George H.W. Bush's heartbreak

James Baker III, George H.W. Bush's former secretary of state, was among the last to visit him before he died in 2018. Recognizing his old friend, he asked (via The Seattle Times), "Where are we going, Bake?" When Baker replied, "We're going to heaven," the former president agreed: "That's where I want to go."

That was November 30, and those who knew him best had been surprised that he had lived that long after burying his beloved Barbara in April. When he was hospitalized days after her death, ABC News says that those closest to him were preparing for him to follow her. His White House photographer said, "... we thought, you know, he's just dying of a broken heart." He was also suffering from vascular Parkinson's (via the Parkinson's Foundation). According to The Michael J. Fox Foundation, this particular condition is caused by a series of small, sudden, and unpredictable strokes that impact a person's mobility, balance, and ability to speak.

Bush had been confined to a wheelchair since 2012, and in 2017, he was the target of accusations of improper touching and groping while posing for pictures. According to USA Today, medical experts had confirmed that his diagnosis included possible symptoms like performing "behaviors that are not voluntary — not entirely under their control or volition." They cited things like Bush's seemingly forced smile as evidence, noting that it was a common symptom known as "abnormal grimacing." His passing was peaceful.