Lesser Known Heroines Of World War I

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

In 2014, the BBC asked, "Why are so few WWI heroines remembered?" The answer — which came, in part, from University of Leeds professor Alison Fell — was a heartbreaking one. At the time, it was almost a global idea that it was men who were supposed to head out and fight while the women stayed home, kept the fires burning, and probably made some sandwiches. The upheaval of WWI that saw countless women picking up arms, heading deep into enemy territory as spies, and heading out into the workplace — and the laboratory — wasn't just an instance of women doing their part, it was the complete opposite of what society had expected form them for a long time. And society wasn't a fan.

Even the nickname given to women warriors — "she-soldiers" — was kind of a tongue-in-cheek thing. It was plucked out of folk stories, and it suggested they were somehow mythical, otherworldly, unreal creatures. It followed, then, that once the fighting stopped, the women who went against all societal norms weren't remembered in a good light.

Let's change that, and talk about some of the most incredible, unsung heroines of WWI.

The scientist who made the WWI trenches just a little safer

Not all heroism happened on the front lines: According to Massive Science, Hertha Ayrton started patenting her inventions when she was still in college, but it wasn't until 1910 that her war work started. That was when she started studying wave dynamics, and wrote a paper called The Origin and Growth of the Ripple Mark. Fast forward a bit, to WWI and the rise of trench warfare.

It was horrible, bloody stuff, and the use of deadly gases was common. Troops in the trenches didn't have a chance when they were doused with things like chlorine and mustard gas, which would almost immediately start eating away at the skin and lungs. That's where Ayrton's work came in. She used her findings on wave and ripple patterns to create a fan that could be used to effectively clear gas from the trenches. Shockingly, the British War Office was having absolutely none of working with a woman, until the media got wind of the potentially life-saving invention that was being ignored. Ultimately, 104,000 Ayrton fans were made and distributed to the front lines (via the Jewish Women's Archive).

Still, as a woman, she wasn't allowed membership in the Royal Society (and she couldn't speak in front of them, either), and when she died in 1923 of septicemia, her obituary called her "a good woman, despite of her being tinges with the scientific afflatus."

The poet who built a hospital on the front lines

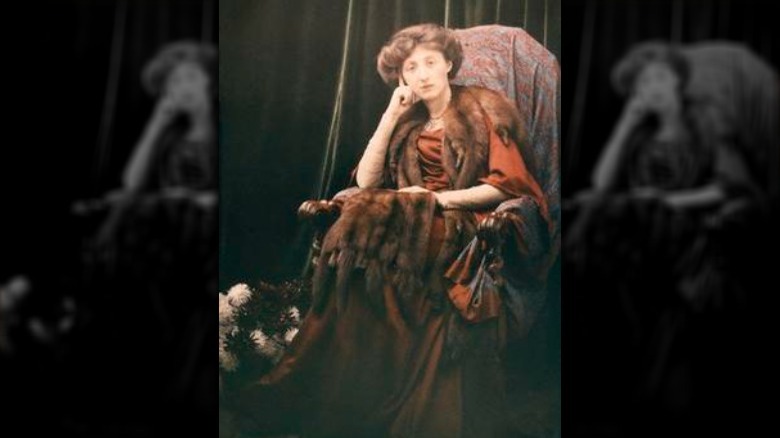

At a glance, Mary Borden (center) might seem like the least likely person to head off to war: She was, says the Smithsonian, born to a rich Chicago family at the end of the 19th century — from there, she became known for scandal, poetry, and as a campaigner for women's rights.

She was 29, married, and a mother of three when she decided to put the fortune she inherited to good use. According to The Guardian, it took a huge amount of convincing before the French government allowed her to not just fund the construction of a hospital on the front lines, but to head there and run it herself. Once the French relented, she got her hospital up and running. It was massively successful: in the first six weeks their doors were open, they saw 25,000 wounded soldiers.

One of her patients would be a British officer named Louis Spears (back row, left), and he and Borden fell wildly, passionately in love. They embarked on an affair that Borden documented in her poetry, and her marriage ended when Spears's ex-girlfriend sent Borden's husband some of the letters she'd written. They ended up getting married, and Borden continued the wartime work she'd begun in WWI through other conflicts — specifically, through WWII, where she organized and funded a mobile ambulance unit that saved countless lives.

The teenage resistance fighter who helped the Allies reclaim her city

Émilienne Moreau was 17-years-old when her French town of Loos-lez-Lens fell to German occupation. When the local teacher was sent to the front lines, she organized the local students into an impromptu school... but they weren't just learning.

Moreau went to the local authorities and asked for permission to take her students out to collect coal at night. Permission was granted, but they weren't just collecting fuel, they were watching, too — so when the Scots 9th Battalion Black Watch moved in, they had a huge amount of intel to share with them. It was information that helped lead to the liberation of the city and minimal losses for the Scottish troops, but she wasn't done yet, says Fondation de la Resistance. In the aftermath of the fighting, she also set up and worked at a field hospital in her own home, only stepping away long enough to grab a gun and take out a group of German soldiers that had holed up in a nearby house.

Moreau went on to become an invaluable part of the French Resistance during WWII, as well. She died in 1971 (via Loos 1915).

Grace Banker and the Hello Girls

Grace Banker was a 25-year-old telephone operator working for AT&T when, in 1917, she came across a US Army ad in The New York Post. She fit the bill, applied, and was ultimately appointed the head of a group of 32 switchboard operators who were sent to France. Once there, this small group would be responsible for connecting and translating around 150,000 coded messages every day. The information was highly sensitive and often top secret: Banker later explained (via The New York Times), "every command to fire or cease-fire or advance or retreat ... was made by telephone."

And even as they fought off exhaustion and illness, they needed to be at the top of their game, Code words changed regularly, couldn't be written down, and needed to be memorized and recalled in a split second, sometimes under heavy fire. The World War One Centennial Commission says the 223 women who eventually made up the corps were known as Hello Girls, and after writing about months of long days, longer nights, and artillery fire that made "the old flimsy barracks shake ... as though in a miniature earthquake," she was able to write about relaying the message of Armistice.

Banker received a Distinguished Service Medal in 1919, but the women of the telephone corps weren't considered veterans — an oversight that was only corrected by President Jimmy Carter in 1977. By then, Banker had been gone for 17 years: She died of cancer in 1960.

The Women's Battalion of Death

When WWI kicked off, it was still seen as a pretty improper place for a woman to be... unless, says Owlcation, she was caring for the men. Regulations loosened a bit as the war dragged on, but it was early on — in 1914 — that Maria Leontievna Bochkareva made it clear that she was having none of that nonsense. After applying for and getting a special exemption from Nicholas II that allowed her to fight on the front lines, she started out her military career by fighting for respect — and then, heading into No Man's Land to recover dozens of her wounded comrades. She was, herself, wounded several times: Among those injuries was an incident where shrapnel lodged in her spine, and — after being paralyzed — she needed to teach herself to walk again. Then, she returned to active duty.

In 1917, Bochkareva formed the 1st Russian Women's Battalion of Death, and 300 women joined. In June of that year, they spearheaded a push into No Man's Land, and secured three German trench lines. According to The New York Times, she would later write in her 1919 memoir, "My heart yearned to be there, in the building cauldron of war, to be baptized in its dire and scorched in its lava. ... My country called me."

Her story doesn't have a happy ending. In the aftermath of the war, Bolshevik police arrested and interrogated her. Deemed "an enemy of the people," she was executed in 1920.

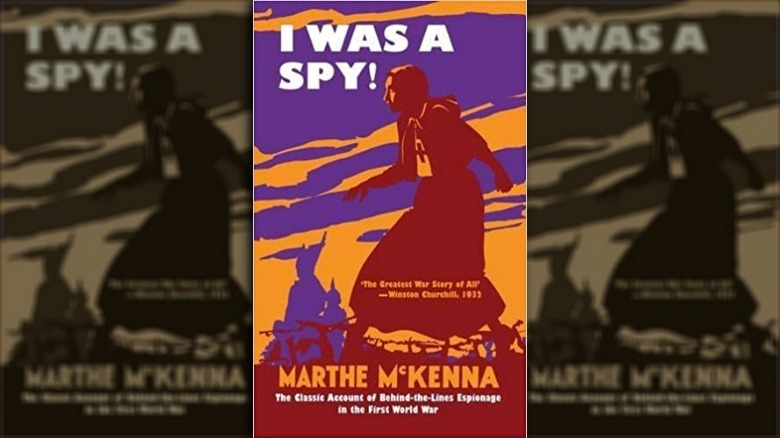

The WWI nurse who was a spy

In a story plucked right from a Blackadder episode comes the tale of Marthe (Cnockaert) McKenna, a Belgian nurse who spent two years using her position to spy on German soldiers. The New York Times says that in 1915, her native Belgium was being occupied by the German forces. Even as she cared for — and oftentimes befriended — their wounded, she was keeping her eyes and ears open to record details on sensitive, valuable information that she would then pass on to her Allied contacts. Sometimes, those contacts were "a hand — white against the darkness" that reached through a window, and that takes some serious bravery.

Even as she helped Allied POWs escape, the Germans awarded her devotion to their cause with an Iron Cross. It was a good thing, too — a lost, engraved wristwatch cast suspicion on her in 1916, and when she was discovered with coded messages in her possession, the usual sentence of execution was waived because of her Iron Cross.

She survived the war, and went on to become highly decorated, marry an officer in the British military, and write her memoir (pictured). It's believed that the book about her life stretched the truth more than a little bit, but her contributions to the Allied cause — and the thanks she received from the Belgian, British, and French authorities — speak for themselves.

The anesthesiologist and the surgeon

During WWI, the idea of a female doctor was nothing short of absurd. Sure, women could be nurses, but doctors? That was just silly. And that's what makes the Endell Street Military Hospital so incredible. According to The New York Times, every doctor, surgeon, dentist, pathologist, and ophthalmologist in the institution was female. And that was by design: the hospital was the work of a surgeon named Louisa Garrett Anderson (right) and her partner, Scottish anesthesiologist Flora Murray (left). As women in the early 20th-century medical field, they knew perfectly well what they were up against: an attitude summed up by a Royal Army Medical Corps officer who simply lamented, "Good God! Women!" when he learned about their project to fill in where there was a desperate need for medical care.

Anderson, Murray, and their staff proved him wrong very quickly. The hospital was up and running by May of 1915, and as many as 800 wounded soldiers arrived every month. These were no ordinary wounded, either — these were wounds that no doctor had ever needed to repair before, leaving the Endell Street doctors to sort of make it up as they went.

By the time wartime casualties waned, Spanish flu victims were on the rise — and the women of Endell Street treated them, too. Still, the hospital was closed in 1919 — the men had returned to take over — but they're still credited with kicking open the door for women in medicine.

Breaking down the boundaries of flight

Marie Marvingt was, in 1914, cited in anti-feminist literature as being a bad role model because the sports- and competition-loving French woman "competes fervently" and "really tries to win." She also made them eat their words. According to Women in Aviation, she was already the first woman to hold an officially recognized record when WWI broke out. There, she became the first woman to fly in combat, and she had already laid the groundwork for an even more far-reaching impact: She designed a prototype for an airborne ambulance and campaigned for their widespread use.

Her push for aerial ambulances hit a hiccup during the war, and when her plan to disguise herself as a man and head to the front lines failed, she headed to Italy — where she joined up with the 3rd Regiment of Alpine Troops. Her bombing run — which spelled the end for a military base in Metz — earned her some of the highest military honors available, and it wasn't long afterwards that she hit on another brilliant idea: Skis as landing gear on planes.

After the war, she continued her push for the creation of air ambulances, and in 1935, War History Online says she officially became the world's first Flight Nurse, then established the Flying Ambulance Corps. Marvingt died in 1963... but not before taking a 176-mile bike ride to Paris for her 86th birthday.

She was nicknamed The Joan of Arc of the North

Louise de Bettignies grew up in a family that was the very definition of old money. Her education — and the fact that Vanity Fair says she spoke English, Italian, and German in addition to her native language — would serve her well when she decided to head off and become a spy in hopes of helping to break the stranglehold occupying Germany had on her home.

She was recruited by the British, and it wasn't long before she rose to the head of an entire network of spies, informants, and resistance fighters. The network, says Remembrance Trails, was called Alice, and she regularly went by the name of Alice Dubois. She and her group of between 80 and 100 informants provided invaluable information on everything from the location of occupying officers' homes to troop movements. It wasn't just information they were passing back to the British, either — they were also smuggling Allied soldiers out of enemy territory.

Under her guidance, the network expanded into several neighboring areas... until the inevitable happened. Her frequent travel put her on German radar, and she was arrested in October 1915. Imprisoned in horrific conditions, she developed pleurisy (an inflammation of the lungs), and she died in September 1918.

The doctor who refused to 'sit still'

The Lancet says that Elsie Inglis (front, with dog) was already well-established as something of an anomaly — a female doctor — when WWI was declared. She'd been a licensed physician for 23 years, but when she went to volunteer, she was told, "My good lady, go home and sit still." Sit still, she did not — and it saved countless lives. Realizing that women were being vastly underutilized, Inglis began assembling a series of all-female medical units who were willing to go anywhere they were needed. That became the Scottish Women's Hospitals for Foreign Service, and the first group was sent to France in 1914.

Still, Inglis wasn't content to sit in safety and just manage the organization from a distance. When a Serbian unit was suddenly left without a head, Inglis headed out — only to find a disease-ridden institution that was struggling under regular bombardment. She was back home in 1916, but found herself in Serbia yet again when, later that same year, she was asked to go help set up another Serbian/Russian unit.

At that point, it's likely she was already well aware that she had terminal bowel cancer. Still, she oversaw the setup of the new hospital, was lauded by everyone involved, and collapsed even as the wounded from the Russian Revolution flooded her doors. Staying until all Serbian units were evacuated, she returned to Britain on November 25, 1917, and died the next day.

Documenting medicine on the front lines

When the United States knew that it was inevitable they were going to be joining the war, they put out a call for medical professionals. Still, it didn't include women, and those women who did want to serve their country could only sign on as what was called "contract surgeons." In short, JSTOR says it basically meant they needed to do all the work and make all the sacrifices, and agree not to get a pension or military rank.

It was a thankless job done by many, including Dr. Loy McAfee. The Georgia-born physician had something of a unique skill set, and had spent 16 years in the medical publishing field when she was dispatched as a contract surgeon (via the National Institutes of Health).

At the time, she was also working for the US National Library of Medicine, and went on to co-write and co-edit a 15-volume series called the Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion (via the Smithsonian). The series covered every aspect of medicine during the war, from tried-and-true treatments to newly invented ones, from long-known illnesses to new conditions and injuries. She was credited as being a vital component that made the series possible, in large part because of her obsession with accuracy and details. Since then, the treatise has been an invaluable part of medical history.

McAfee died in 1941, after complications from a stomach operation.

Putting an inheritance to good use

War is a weird thing, and no matter what someone's skill set, there's a chance for them to do some serious good. Take Julia Hunt Catlin Park Depew Taufflieb. All those names came from her various husbands, and given that she was born into the life of a socialite, it might be easy to expect she'd be content to watch from a distance.

Not so. According to the World War One Centennial Commission, she almost immediately started funneling money into turning her French estate into a military hospital. For four long years, she completely ran and funded the 300-bed hospital.

She was also responsible for aiding 1,500 refugees, and Women's History says she raised around $100,000 in today's money for her refugee aid work. Other privately funded hospitals opened based on her work, and she ended up marrying a French General (named Taufflieb), and after temporarily leaving ahead of the German advance, she returned before she died in 1947.

The young girl who turned herself into a man, then went to war

For years, the only known mention of her was as a person named "W," who had been responsible for guarding supplies in occupied Serbia. That's just a small part of the fascinating tale that is the story of Leslie Jo Whitehead. Whitehead, says Britic, was a 22-year-old from Canada when she headed to war. Initially, she worked in London as a correspondent sending news back to Canada, but it wasn't long before she'd had enough of that — so, she headed to Serbia and joined up with the Serbian Relief Fund. From there, she disguised herself as a man, enlisted in the Serbian Army, and became one of her unit's star sharpshooters.

It was there she was tasked with guardian supplies from would-be attackers, and it was also there that — according to Historians for History — she made it a point to get friendly with her other soldiers who, thinking she was a man, would share their deepest desires with her. She, in turn, would use that information to protect the women around her from sexual assault.

In 1915, she was taken prisoner by Bulgarians (which is where she would meet her future husband, Vukota Vojinovic). After several months, she was freed: She and her husband returned to Canada, and she died of stomach cancer in 1964.

The activist who made sure munitions workers were no longer overlooked

Combat on the front lines was driven by munitions made back home, and making the explosives and artillery that soldiers relied on was thankless work. In Britain, thousands of women labored in potentially deadly factories in order to keep their soldiers supplied with ammunition. Not only were munitions factories considered high-profile targets, but explosions weren't uncommon, and the chemicals they handled every day turned them bright yellow. That, says the BBC, is why they were called Canary Girls.

And this is about where Mary Reid Macarthur comes in, says the Black Country Living Museum. In 1915, laws made it illegal for workers to strike, which took away a lot of their ability to protest unsafe working conditions, strike, or even quit their jobs — even if they were getting paid next to nothing. Macarthur was already a well-known women's rights activist, and went to the government. It was her position that if the government was locking them into a job, then they'd better guarantee safe working conditions and a salary that matched the work that was being done.

Macarthur absolutely came through, getting wage increases for the women, and access to tribunals who would mediate workplace disputes. She became the go-between that made sure women — many of whom were the sole support for their families — were paid what they were promised, and on time.

She died in 1921, of stomach cancer. She was 41.

The only female British soldier

Front-line opportunities for women in WWI were few and far between, and when Flora Sandes was rejected from medical service because of a lack of medical training, she didn't take that as a satisfactory answer. Instead, she headed to Serbia and, after working for a time in their hospital units, she got her chance to fight.

History Ireland says that the Serbian Army was falling in the waning months of 1915, and that's when Sandes decided to accompany the army on what was called the "Great Retreat." Her fellow soldiers were so impressed with her skills that she was formally moved from the Red Cross into a combat role, and would later write that it wasn't her female-ness that set her apart, but her Englishness. "It was heartbreaking the way they used to ask me every evening, 'Did I think the English were coming to help them?' ... It was touching, the faith they had in the English."

By 1916, she was back in England after being severely wounded by shrapnel. Once she was back up and on her feet again she was also back in Serbia, where she continued to fight until she was demobilized. That officially happened in 1922, and Historic UK says she had a tough time adjusting to her new life outside of a war zone. She never forgot her fighting days: When WWII broke out, the 65-year-old Sandes enlisted and headed to Yugoslavia. She died in 1956 in Suffolk.

Fanny goes to war

The First Aid Nursing Yeomanry Corps was formed in 1907, and early FANYs weren't just nurses, they were women who rode out onto the battlefield where they became "proficient in the art of swooping down upon a wounded soldier at high speed, scooping him up behind the saddle and delivering him to the First Aid Post" (via First Aid Nursing Yeomanry). By WWI, many (like the unknown woman pictured) had transitioned to becoming ambulance drivers instead of equestrians, but the danger level was about the same. Thanks to an ambulance driver named Pat Beauchamp, the experience shared by the FANY drivers was preserved in her memoir, "Fanny Goes to War."

According to Nursing Clio, her book is one of the few first-hand accounts that document the experiences of female ambulance drivers on the front lines, simply because at the time, most of the focus was on the work being done by nurses. Being a driver was a little too "masculine" for most to acknowledge at the time, especially considering they weren't just driving, they were off-road navigators in unfamiliar territory who also needed to be able to be on-the-fly mechanics, too.

Beauchamp described it all, from the physical and emotional toll it took on her to her own injuries: She lost her leg when her ambulance was hit by a train. In addition to saving lives, she also made sure the sacrifices of her fellow drivers wouldn't be forgotten.

The female Lawrence of Arabia

Gertrude Margaret Lowthian Bell could have kicked back and enjoyed the easy life: According to English Heritage, she had the good fortune to be born into one of England's richest families. By the time she was in her 20s, she embarked on a series of expeditions across the Middle East, and it laid the groundwork for what followed next in WWI.

That, says Biography, is when she became the only woman working for the British government in the chaos that was the Middle East. She was stationed in Cairo alongside TE Lawrence, and tasked with raising support for the British efforts to oppose the Ottoman Empire. Historic UK also credits her with being instrumental in gathering the information that would go leaps and bounds toward defeating the Turks and leading to the fall of a centuries-old empire.

She was so good at what she did that she was invited to the post-war Paris Peace Conference, and on the heels of that, she was charged with establishing Iraq as a country. That included drawing borders and installing a new king, and she was so widely respected in the area that she was given the informal title of khatun, which translated to "respected lady" or "queen."

Documenting the front lines of WWI and beyond

The National Portrait Gallery says there's a few things that make Olive Edis revolutionary: Not only was she one of the first female war photographers on the front lines, but her work as a portrait artist gave her a unique perspective and allowed her to capture images that tell the story of the people rather than the scene.

During WWI, she was sent to France and Flanders, and specifically set out to document women in war. The resulting photographs are deeply personal, and serve not only to preserve the memory of the women working on the front lines, but her more candid shots are a reminder that behind the smoke and blood, life went on.

According to HistoryExtra, Edis was instrumental in redefining the role of women in active combat as chroniclers. Until Edis was dispatched into an active war zone, war photography was seen as a "masculine" field, dominated by male photographers taking photos of male soldiers. Edis, on the other hand, became a female photographer documenting the wartime struggles and sacrifices of women, helping to ensure that their part in the war was preserved for future generations.