The Truth About The Intense Manhunt For Adolf Eichmann

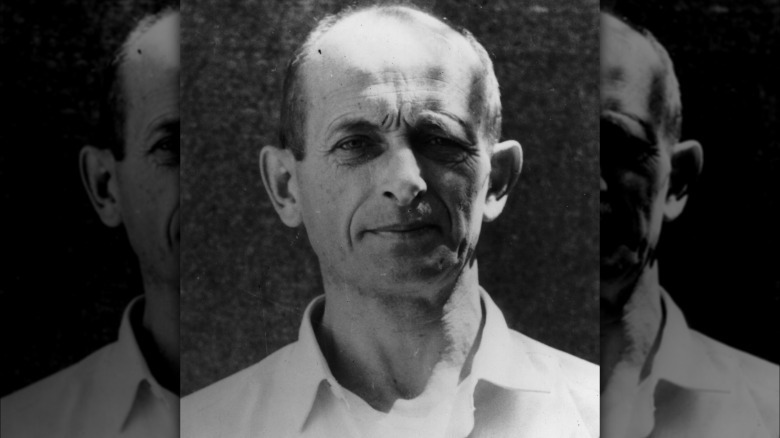

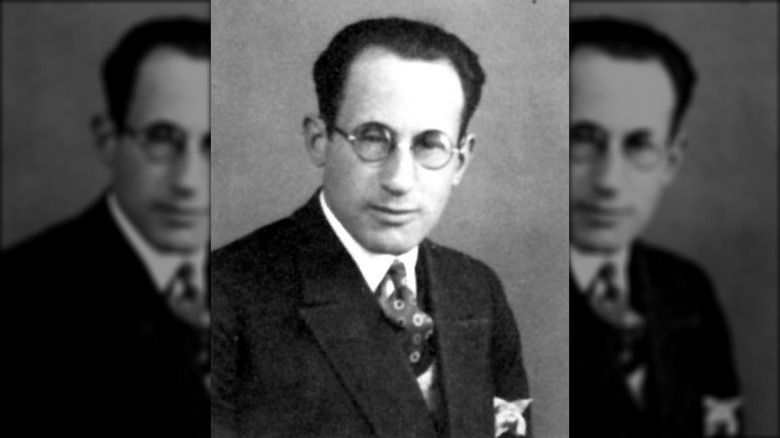

Adolf Eichmann was one of the key players in the design of the "Final Solution," the Nazi plan that called for the genocide of all Jews during World War II. Eichmann himself formulated the logistics of the Holocaust, especially the deportation of Jews to extermination camps.

During the 1942 Nazi Wannsee Conference, Eichmann was put in charge of coordinating the "final solution." He was in charge of identifying, gathering, and transporting Jews from occupied Europe, first to ghettos and then eventually to extermination camps like Auschwitz. By the end of the war, he had sent millions to their deaths.

Eichmann was captured by U.S. forces in 1945 but soon escaped and went into hiding in Germany and Austria for five years. Then in 1950, Eichmann took advantage of the "ratlines," a system of escape routes helping Nazis flee Europe for safer lands. He ended up in Argentina where he lived for several years with his family before he was captured and taken to Israel to stand trial for his war crimes. But his capture was stealthy and clandestine, and during his trial, he denied being anything more than an "instrument" of the Nazi party.

Eichmann was one of the key planners of the Holocaust

During and after his trial, Eichmann would notoriously claim that he was only following orders. However, a close look at his wartime activities shows that he and other Nazis were hardly "forced to serve as mere instruments," as he claimed in a 1962 letter (via The Guardian). After an early adulthood of unimpressive academic work and mundane jobs, Eichmann became a Nazi in 1932. He was so dedicated to the new direction his life had taken that, when Austria banned Nazi membership the next year, Eichmann moved back to Germany, the country of his birth. He proceeded to work his way up the party ranks, directing efforts to surveil Jewish people, oversee raids, and push them out of German territory. He worked particularly to promote the emigration of Jewish people, which then turned into their deportation.

By the early 1940s, Eichmann was deporting people to killing centers in Poland and Nazi-controlled parts of the Soviet Union. Later, Rudolf Hoess would claim that Eichmann personally visited Auschwitz and inquired about its deadly techniques. Eichmann became known for his ruthless organizational skills, which he used to more efficiently identify and transport people who would be murdered in the Holocaust. Between April and July 1944, Eichmann oversaw the deportation of 440,000 Hungarian Jews, and at Auschwitz alone, Eichmann's work sent hundreds of thousands of people to their deaths, with Eichmann allegedly expressing satisfaction that he made it happen at top speed. Others later recalled him as a brutally efficient manager who was key to the whole process.

Eichmann was initially captured, then escaped

Just after the end of the war, Eichmann was detained by U.S. forces and put in a prison camp. But, as the Nuremberg trials were set to prosecute some of the worst offenders of the Nazi regime, including Hermann Göring and Rudolf Hoess, Eichmann managed to escape in 1946. For years, he lived surprisingly close to home in Northern Germany, though under the assumed name of Otto Henninger. He obtained his identification papers through sympathetic Nazi-aligned Germans and Austrians, while a former SS member got Eichmann a forestry job. For a while, he even tried his hand at chicken farming (in a weird coincidence of the war, both Himmler and anti-Nazi agent Juan Pujol Garcia were also failed chicken farmers). By the early 1950s, even the Americans who had previously hunted for him were devoting their attention to the Cold War with the Soviet Union, while Israeli forces were preoccupied with establishing their nation.

That never meant Eichmann felt totally comfortable living an unremarkable life in an isolated region of Germany. By the 1950s, he began traveling, eventually using Italy as a departure point for his journey to Argentina.

New horizons awaited on the other side of the ocean

"Ratlines" were secret escape routes that Nazi war criminals used with the aid of sympathetic parties to get out of Germany, and were mainly directed toward South America — Argentina, Brazil, and Paraguay. This was in large part the result of Argentinian President Juan Perón encouraging Nazis and collaborators to come over. Understanding the "why" is hard, and it was probably the result of many factors. Although Argentina remained neutral during the war, Perón aided the Axis powers in secret. Anti-Semitic immigration laws in Argentina and Peron's admiration for both Italian fascist Benito Mussolini and Germany's well-organized military power might have played a part, too.

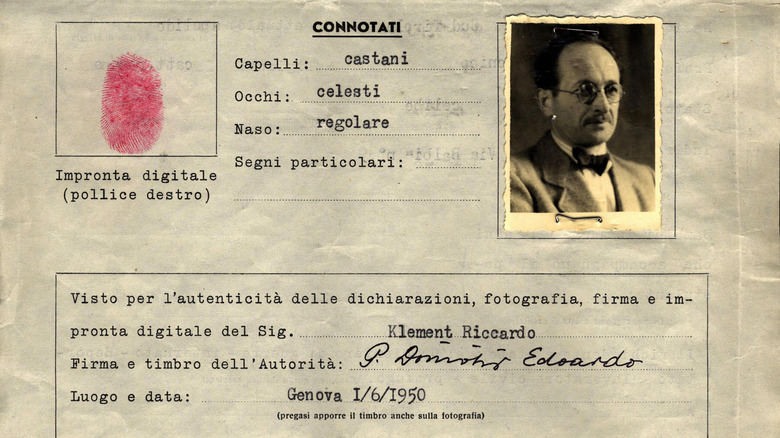

So did leaders of the Catholic Church. Perón's agents helped coordinate escape routes with Catholic bishops, who provided hiding points (mainly monasteries and churches) to Nazis who were escaping Germany and making their way towards Italy. Once in Rome and Genoa, the two main meeting points, the church would help war criminals obtain falsified Red Cross passports and visas. Argentina, a country of European immigrants, also had a large German community that helped bankroll the operation. As a thank you for the help of the church, Eichmann converted to Catholicism later on, per Deutsche Welle.

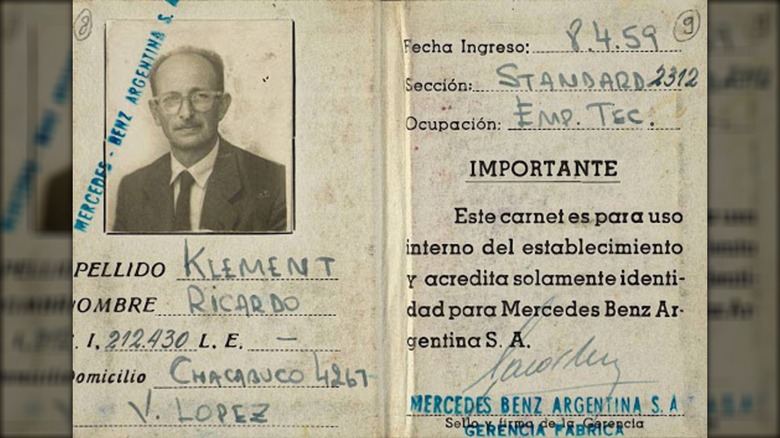

In 1950, Eichmann boarded a steamship toward Buenos Aires, Argentina, where he would live a quiet, undisrupted life for the next decade. He arrived in Argentina under the name Ricardo Klement. However, if anyone had been paying close attention, they might have noticed that in 1952, Eichmann's wife and children — who had once been monitored by the Allies — left Germany to join "Ricardo" in Argentina.

For the first two years, he worked at CAPRI, a hydroelectric power plant company owned by German-Argentine businessman and Nazi sympathizer Horst Carlos Fuldner. This was the first employment stop for many Nazis arriving in Argentina, according to Spiegel International.

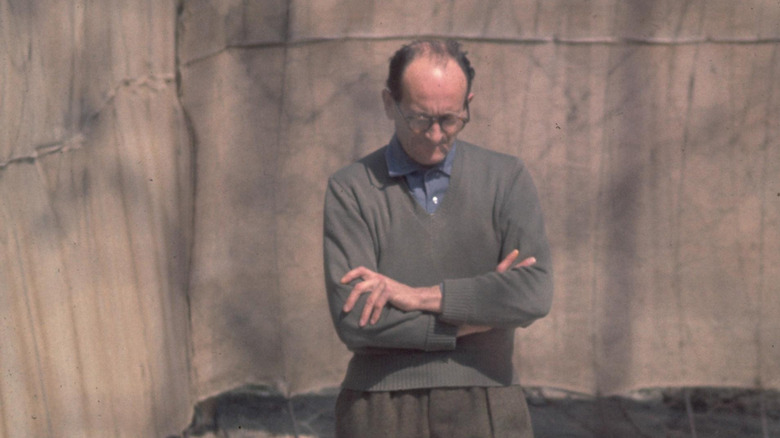

He wasn't strictly living quietly in Argentina

The point of leaving Europe for another continent was to keep his identity secret, but Eichmann wasn't exactly doing a top-notch job of remaining concealed. For one, he joined an expatriate community of Germans and Nazi's living in Argentina. Certainly, given how Argentine president Juan Perón was a big fan of fascism and helped make the way for ratlines that brought former Nazis to his country, few people in the immediate area were asking questions. Still, Eichmann couldn't help but connect with other former Nazis, including Josef Mengele, who was so bold as to go by José Mengele on occasion and, unlike Eichmann, was one of the Nazi war criminals never brought to justice. Even some of his coworkers at the hydroelectric company CAPRI knew that Ricardo Klement was actually someone named Eichmann. It probably didn't help that Eichmann reportedly demanded his sons continue to use the original family name.

Eichmann eventually met with Willem Sassen, another former SS member and journalist, to record hours of interviews in anticipation of a future book. In the tapes, recorded in 1957 and spanning over 70 hours, Eichmann clearly admitted to his role in the Holocaust and expressed happiness with his genocidal work. However, only a portion of the tapes were made available to prosecutors during Eichmann's trial, and access to the long-lost Eichmann tapes has been piecemeal up into the 21st century. But the transcripts and recordings that have been released show Eichmann outlining his crimes at length and with no remorse.

A relationship between Eichmann's son and a neighbor proved to be a turning point

One man was eventually willing to take a second look at Ricardo Klement — because his daughter was getting involved with one of Eichmann's children. Specifically, Lothar Hermann's daughter Silvia had begun to date the neighbor boy. Lothar was a Holocaust survivor who had made it out of Dachau, though he eventually lost his eyesight as a consequence of beatings from the Gestapo. Even without his full vision, something about the boy's father didn't seem right to Hermann. Eventually, the Hermanns moved far away from Buenos Aires, but then Lothar heard of Nazi trials held in 1957 and began to recall his unnerving neighbor.

What raised his suspicions? Some sources indicate that the Eichmann boy, who'd dated his daughter, visited their home and, unaware that Lothar was half Jewish, began making derogatory remarks about Jewish people. He also said that his father had been in the war, while Silvia was never invited to visit her boyfriend's home or meet his father. Oh, and also the young man's last name was Eichmann. It was enough for Hermann to send a tip back to Germany, letting officials know of his suspicions. Frustrated at a lack of action, he began to tell even more people and, when Israel began to show interest, would fuss at Mossad agents for moving too slowly. Hermann's information eventually made its way to Fritz Bauer, the attorney general who would provide the next burst of momentum to catch Eichmann.

The CIA knew something about Eichmann's whereabouts but didn't move to apprehend him

While attention was slowly beginning to circle in on Eichmann in Argentina, the Americans and Germans were keeping a secret. At least two years before Mossad agents snatched Eichmann off the streets of Buenos Aires, the CIA had a pretty good idea where Eichmann was hiding, as did the BND, West Germany's intelligence agency. Other foreign intelligence services may have also known about Eichmann's life in Argentina, though other nations haven't fessed up to having that information.

What did the CIA really know? A decent amount, it seems, though not much on which to base an investigation. By 1953, a CIA memorandum claimed that "we are not in the business of apprehending war criminals," but didn't hint at any real knowledge of Eichmann's whereabouts (via National Archives). It did get a significant tip by 1958, when CIA documents indicate that the BND knew Eichmann had lived in Argentina under the pseudonym of Clemens (the report also included a rumor that he was in Jerusalem). Some at the agency may have worried that moving too soon would alert Eichmann and push him into deeper hiding. Still, after Eichmann's capture, CIA officials fretted that, if their prior knowledge came to light, they would be subjected to many embarrassing questions. However, the Eichmann information did not come to light until 2006, when the agency declassified thousands of pages concerning its work with postwar Nazis.

A German judge was key in Eichmann's capture

Fritz Bauer, a German-Jewish survivor of the war (who was also persecuted for being gay), was hardly a friend to Eichmann. He became a judge in 1930, then was sent to a concentration camp three years later. His release came at the cost of signing a loyalty pledge to the Nazi regime and hardly assured his safety; Bauer eventually fled the country for the rest of the war. He returned to Germany — or at least West Germany — in 1949, again taking up his work as a judge. Bauer found others weren't ready to let go of the Nazis or their deadly ideals, but he still worked to prosecute Nazis, a mission that garnered him death threats.

By 1957, Bauer was the chief state prosecutor. When he got word that Eichmann was perhaps hiding out in Argentina, he kept it from other German officials, fearing they would be too easy on the architect of the Holocaust. Instead, he got into direct contact with Lothar Hermann, sending him a description of the fugitive Eichmann. Hermann and his daughter Silvia traveled back to Buenos Aires and found the Eichmann home. When Silvia knocked on the door, Eichmann himself answered and confirmed that he was her old boyfriend's father. That was enough for them to confirm to Bauer that Eichmann was living at that address. Bauer sent this information directly to Israel's Mossad intelligence agency. When the Mossad proved only quasi-interested, Bauer pushed them to get into contact with Hermann, which convinced them that Klement really was Eichmann.

A doctor essentially puppeted Eichmann through the Buenos Aires airport

Though Eichmann was in Mossad custody, hardly anyone expected him to meekly sit on a plane the whole flight to Israel. It didn't help that the El Al Israeli flight they had meant to transport Eichmann was delayed, meaning they had to wait more than a week in a safehouse. When the time finally came to board the plane, they produced a fake passport and pretended that Eichmann was a flight attendant. But success depended on the team's physician, Dr. Yonah Elian.

Elian was an anesthesiologist, though fake documents for the mission claimed that he was an El Al flight navigator. In his professional life, he was well known for his ability to safely and efficiently sedate patients. He gave Eichmann just enough to keep him apparently awake but unable to speak out or run away. The Mossad team told officials in the Buenos Aires airport that Eichmann, guided by Elian, was a sick crew member. However, Elian did not feel entirely settled about his role in the capture, later telling his son he believed he had broken the Hippocratic oath to do no harm to a patient.

Prior to that, during another secret Mossad mission, he had been recruited to sedate a potentially traitorous Israeli army officer. But atmospheric conditions on the plane transporting them had made the sedation go wrong, Elian's patient died, and the mission was covered up. That perhaps contributed to Elian's unwillingness to talk much about his role in the Eichmann capture.

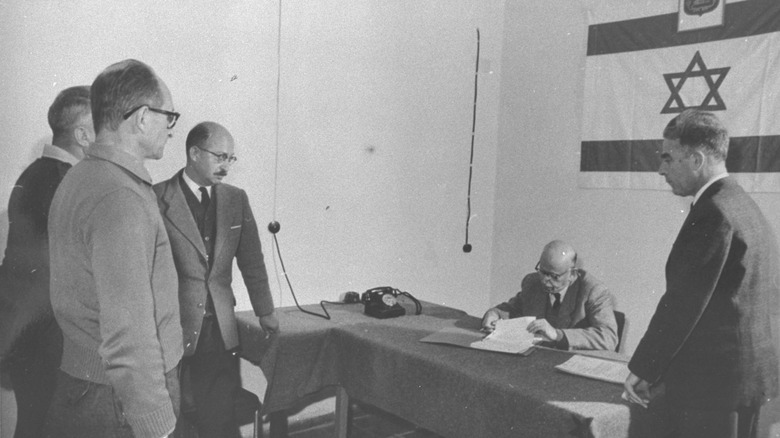

The capture was initially hushed up

With Eichmann finally in their custody, the Mossad agents had a big problem on their hands. How were they to get Eichmann out of Argentina without spurring a major international incident? As much as we may now interpret Eichmann's capture as a step towards greater justice, not everyone then believed it was above board. Did one country have the right to enter another country, seize someone from a third nation, and then bring them to face trial? Israeli officials thought so, but they knew not everyone would agree. Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion only announced the capture in May 1960, after Eichmann was already over the Israeli border. Even his own cabinet was surprised and wasn't totally clear on just how Eichmann had gotten from Argentina to Israel, as Ben Gurion skipped over the kidnapping details. Moving forward, they attempted to keep the focus on Eichmann's crimes and his trial.

That didn't stop diplomatic upset from happening, however. Argentina quickly went on the offensive, going to the U.N. Security Council with a complaint that its sovereignty as a nation had been violated and Israel had broken international law. Eventually, Israel apologized, and Argentine officials backed down, perhaps to avoid the further embarrassment of acknowledging they had sheltered a Nazi war criminal for years. Meanwhile, Austria and Germany, where Eichmann might have claimed some sort of citizenship, were not going to bat for him. So, he was left to the Israeli justice system.

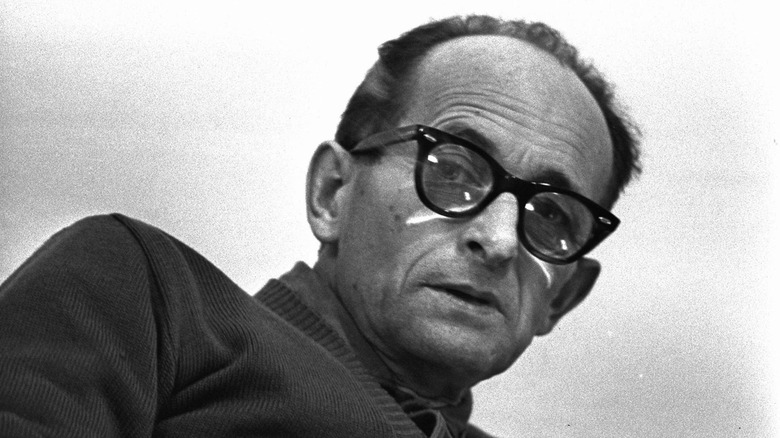

His trial was watched across the world

Eichmann's trial was no small thing, and neither was it a local affair. Instead, the proceedings were worldwide news, though it began with months of interrogations between his arrival in Israel and the trial proper. Eichmann's defense attorney argued that the whole setup was biased and the trial would be better held before an international tribunal. However, the case moved forward in an Israeli court, with Israel's attorney general Gideon Hauser stating that he was speaking for the 6 million Jewish people who had been killed in the Holocaust. Strikingly, some still-living Holocaust victims provided first-person accounts of the horrors they had experienced — all the more striking because the Eichmann trial was televised.

For his part, Eichmann claimed that he wasn't antisemitic and had even engaged with Jewish culture and literature. But when questioned about his exact role in the Holocaust and precisely what he knew about the genocide, Eichmann was evasive. Besides his infamous claim of only following orders, he claimed to be rather squeamish and not know that much about the killing, saying he was only really responsible for arranging transport to the camps ... where few ever left. However, the prosecution alleged that he not only knew what was happening but also worked hard to keep everything moving forward in an efficient manner. Ultimately, Eichmann was found guilty on all counts levied against him and sentenced to death, which was carried out on May 31, 1962. His cremated remains were disposed of at sea.