The Worst Man-Made Disasters In US History

Natural disasters are heartbreaking, from the widespread destruction that just sort of happens because life is sometimes the worst, to the feeling of helplessness as the whole thing unfolds. But just as bad — if not worse — are the tragedies that mankind brings down upon itself.

As awful as things like hurricanes, earthquakes, and tornadoes are, let's talk about the single thing that might make man-made disasters even worse: Humans created them, and that means they absolutely didn't have to happen. People didn't have to die, entire sections of this planet — the only one we have — didn't need to get destroyed, and there's a whole heck of a lot of really bad days that just didn't need to happen.

The past is in the past, though, and the only thing that's left is to pick up the pieces and remember, in the hopes that future tragedies can be avoided. The way to make widespread loss of life, illness, and destruction worthwhile is to learn from past mistakes, so let's try to do exactly that.

Remember when the entire Midwest was pretty much ruined?

There was a lot going on in the 1920s and '30s. Not only did the stock market crash and the Great Depression make life next to impossible for a lot of people, the Midwest was turned into the Dust Bowl.

In a nutshell, it was awful. Once-rich agricultural land was buried under clouds of dust carried in by choking, suffocating storms. Livestock and people alike died by the scores, and crop failures meant hunger spread well beyond the reaches of those storms. Explore the Archive says that more than half a million people found themselves homeless, and another 3.5 million packed up what they could carry and set off in hopes of settling somewhere they wouldn't be smothered by the air.

How did mankind manage to pull this one off? It started with the Homestead Act of 1862, which gave people willing to move west 160 acres of land. Good deal, right? A lot of people thought so and settled in to do some serious farming. Unfortunately, a few decades of tearing up valuable grassland and destroying topsoil meant erosion on a massive scale. History says the entire thing was fueled by a belief that "rain follows the plow," which said the more farming that was done, the better the land would get. The opposite happened: Fueled by a few years of drought conditions, American settlers' westward push resulted in one of the most devastating climate disasters of the 20th century.

America's most toxic ghost town

In 1914, enterprising miners discovered an area rich in lead and zinc. The timing couldn't have been better, and Picher, Oklahoma, became a major source of metals needed during both World War I and II. Wired says the mining done was to the tune of $202 million in sales, around 10 million tons of lead and zinc, and 181 million tons of ore processed.

And then, consequences came.

Sinkholes opened, and parts of the town started collapsing. Heavy metal dust covered everything, and that's also about when the toxic chemicals left behind started leaking into the groundwater. It was so bad that kids who went for a dip in the local swimming holes came back with chemical burns.

And it's continued to be a black hole of toxic waste. Once home to around 20,000 people, NBC says Picher was recognized by the Environmental Protection Agency as one of America's most polluted places, and was designated a Superfund site. Testing showed that into the mid-1990s, 63% of the area's children still suffered from chronic lead poisoning, and in 2000, it was finally ruled officially uninhabitable. Evacuation orders were given, and it ended up being just in time: The Army Corps of Engineers discovered that about a third of the town was sitting above empty chasms, just waiting to collapse.

By 2014, there were only about 10 people still living there, in a desolate, post-apocalyptic sort of way ... and calling the Tar Creek Superfund Site home.

When Michigan was poisoned by a huge mistake

It was 1973 when the Michigan Chemical Corporation made a terrible mistake: They included bags upon bags of the fire retardant polybrominated biphenyl (PBB) in shipments with livestock nutrients. The order was for the Farm Bureau, and when it was received, it was mixed with feed and distributed state-wide.

Veterinarian Alpha Clark was on the front lines and told Bridge MI that it wasn't long before cattle stopped eating and started acting just wrong. By that time, the PBB had gone into the milk, and that milk had been sold at supermarkets far and wide.

It took around a year for authorities to realize what happened, and they ordered the mass slaughter of around 32,000 cows, sheep, chickens, and pigs. Research teams from Emory University immediately started monitoring a small group of people who had been impacted and found many were suffering from thyroid disease — which is known to be associated with PBB. That, says Michigan Radio, is just the beginning.

By 2017, health officials were still monitoring the next generation — those who hadn't been directly contaminated but who were born into families that had been. Higher rates of miscarriages, breast cancer, abnormal thyroid levels, and children with urinary conditions were found, with 60% of Michigan residents still testing with above-average PBB levels. Undark says Michigan residents — like Jim Hall, who lost his daughter Jerra when she was just two years old — link the exposure to continued family tragedies.

The oil spill felt across the US

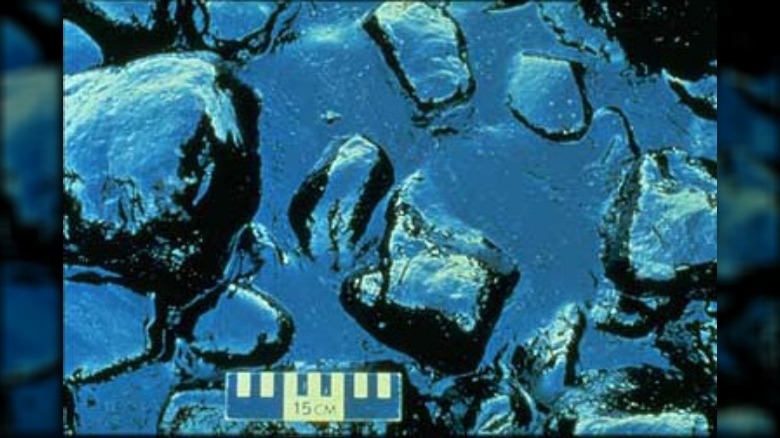

On March 23, 1989, Captain Joseph Hazelwood decided to call it an early night and go have a drink. He turned control of his vessel over to a third mate, and that's when the Exxon Valdez ran aground on Bligh Reef. Around 11 million gallons of oil were dumped into Alaska's Prince William Sound, says History, and the results were catastrophic.

The oil spread to cover around 1,300 miles of coastline, and National Geographic paints a dire picture of the aftermath. The death toll included a quarter of a million seabirds, 22 killer whales, hundreds of seals, and thousands of otters. The salmon and pacific herring populations crashed, and along with them the fishing industry. The economic losses are estimated to be somewhere around $2.8 billion, and when 91 sites along the coast were reexamined in 2001, more than half were still contaminated with oil.

Wildlife populations — including killer whales — were still nowhere near recovery in 2019, and geochemists say that not only is the oil still there, but natural disasters like a storm or an earthquake could dredge up residue that's sunk to the bottom. It was a no-win situation for everyone involved and led to a massive overhaul in the legislation governing the responsibilities of oil companies to make spills like this right.

As for Hazelwood, he was fined $50,000, found guilty on a misdemeanor negligence charge, and sentenced to 1,000 hours of community service.

The bizarre-sounding disaster that was absolutely devastating

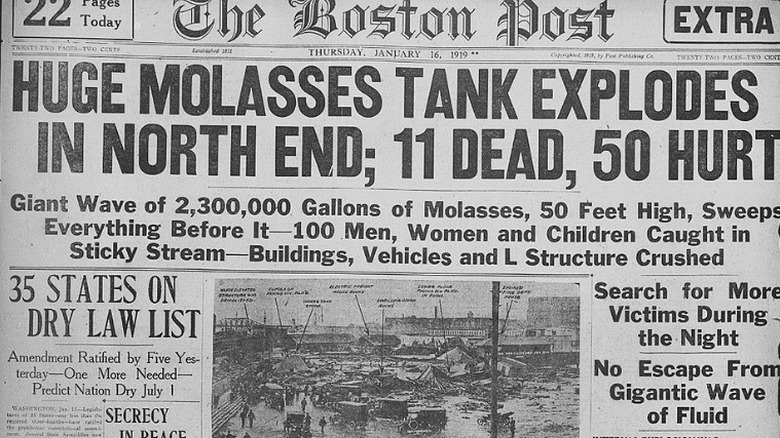

Boston, says History, smelled like molasses for decades ... and not in a good way.

At the same time the world was dealing with World War I and the Spanish flu, Boston was dealing with something else. A massive storage tank — 50 feet high and 90 feet in diameter — had been making weird rumbling noises for a while, and on January 15, 1919, it finally gave way and unleashed a flood of over 2 million gallons of molasses on the unsuspecting city.

The molasses weighed around 26 million pounds and swept through the streets at around 35 mph. Buildings were leveled, train cars were thrown like toys, and people and animals alike died, drowning in the sticky, goopy mess. By the time it was over, 21 people were dead, 150 were injured, and the city sustained around $100 million in damages by modern standards (via History Today).

Investigation put the blame squarely on the shoulders of United States Industrial Alcohol. They had bought the tank specifically for molasses but never tested it — or repaired it, something they were repeatedly told needed to happen. The tank had leaked badly from the first time it was filled, but the company — in an attempt to move as much product as they could in the year-long grace period leading up to Prohibition — completely dropped the ball.

USIA was ultimately found guilty and settled out of court. Cleanup took 87,000 man-hours, and the last body wasn't recovered until four months later.

The dead zone

Ideally, U.S. coastal waters should be filled with life. That's not the case everywhere, though, and since 1986, EarthSky says scientists have been monitoring a massive patch of dead waters in the Gulf of Mexico. In 2019, the so-called dead zone covered a shocking 6,952 square miles (although the size varies annually).

Dead zones happen when nutrient levels in the water reach a high point that encourages algae blooms. The algae continues to grow, and when it dies and then decomposes, oxygen levels in the water plummet. Anything living in these areas suffocates, hence the Stephen King-esque name.

And yes, National Geographic says that people are the cause of this Gulf dead zone, along with other dead zones like the one found in the Chesapeake Bay. Most of the nutrients come from agricultural fields and farms. Runoff carries all kinds of fertilizers from those fields into nearby waterways to kick-start the deadly algae blooms.

The consequences are staggering and far-reaching. In addition to making huge sections of the world's water uninhabitable, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration estimates (via Nature) that Gulf industries lose around $2 million a year. The seafood industry is particularly hard-hit, and considering it's one of the country's most important sources of seafood, that's a huge deal.

When civil engineering marvels go terribly wrong

The Los Angeles Department of Water was formed in 1902, and in 1913, they opened a 233-mile-long aqueduct designed to bring water to the city from Lake Owens. It didn't go well. Not only did the lake start drying up, but locals not thrilled with the terraforming started sabotaging the aqueduct. An alternative was needed really quickly, and that was San Francisquito Canyon's St. Francis Dam.

When it opened in 1926, Smithsonian Magazine says it was one of the largest dams in the world — and when it collapsed in 1928, it filled the canyon with 12.6 billion gallons of water.

Authorities had noticed a severe leak in the dam on the morning it broke but concluded there was no danger upon further inspection. The dam failed that night. No one's entirely sure what happened, as any eyewitnesses were the first to die, but the aftermath was clear: Nearby power plants were crushed, and then the towns of Filmore, Santa Paula, Castaic, Saugus, and Saticoy were wiped out, each one adding more debris to the rolling wave. It continued for 55 miles, swallowing everything on the way to the ocean.

The death toll is unknown — but estimated to be at least 600 — and bodies would be recovered from as far away as Mexico. Chief engineer William Mulholland took the blame but was cleared, and in 1995, it would later be found that they'd built the dam on the unstable foundation of an ancient landslide. There was no chance.

What's a few thousand more dead?

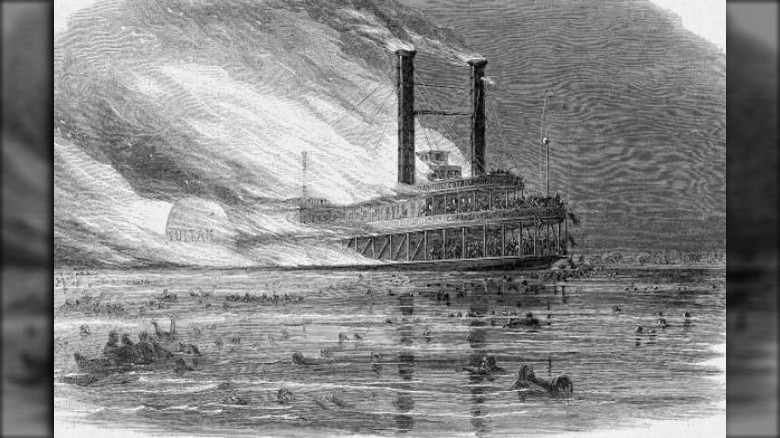

America's worst maritime disaster has been largely forgotten, and Smithsonian Magazine says the reason is heartbreaking. It was the end of the Civil War, and what was another 2,000-ish dead? Thousands of deaths had stopped being news.

It happened on April 27, 1865: The steamboat Sultana was chugging up the Mississippi, laden with newly freed Union POWs, when the boilers exploded. There were around 2,300 people on board, and around 1,800 of them were killed. Those who were saved were largely rescued by the communities along the riverbanks — communities who had supported the Confederacy only weeks prior.

So, what happened? Greed. The Sultana's captain was J. Cass Mason, and the American Battlefield Trust says that he was one of many who were contracted to ferry Union POWs back home to the North. Captains were involved in what was basically a bidding war for getting men on their ships, and the Union Army's Captain George Williams ordered 2,300 men on board the ship that was only rated for carrying 376. Meanwhile, Mason welcomed them, in spite of the fact that he knew the ship's boilers were leaking.

The severe overcrowding strained the boilers to bursting, and bursting is exactly what they did. Most died in the initial explosion, some drowned as they tried to swim to shore, and hundreds more later succumbed to their burns. When it was over, it was the highest loss of life in any U.S. maritime disaster, surpassing even the Titanic.

US history doesn't just happen on US soil

The world's worst industrial accident happened in Bhopal, India, on December 2, 1984, when a local chemical plant released somewhere around 40 tons of toxic gas into the environment.

Omwati Yadav can see the plant from her home, and in 2019, she told The Guardian: "It would be better if there was another gas leak which could kill us all and put us out of this misery. Thirty-five years we have suffered through this, please just let it end. This is not life, this is not death, we are in the terrible place in between.

Around 3,000 people were killed instantly, and around 574,000 were poisoned — left to suffer cancers, heart and lung diseases, thyroid disease, kidney disease, tuberculosis, miscarriages, and slow, painful deaths. The next generation has also been found to have a shockingly high instance of conditions like autism, cerebral palsy, and developmental disabilities.

What does this have to do with U.S. history? The plant, says Chemical & Engineering News, was Union Carbide's, and they're an American company (now owned by Dow Chemical). The company paid Bhopal's state, Madhya Pradesh, $470 million in 1989, but the damage done has long surpassed that. Not only have tens of thousands of people died since, but there was no cleanup operation, toxic waste continues to spread today, and those most immediately impacted still condemn the U.S. government for forcing them to live beneath "a toxic sword of Damocles over their heads."

California's deadly 2018 wildfires should have been prevented

In 2018, the world watched in horror as blazing wildfires ate their way across the state of California. Along the way, they consumed most of the 27,000-resident town of Paradise, killed 86 people, and destroyed nearly 20,000 buildings. It wasn't just the fire that was deadly: In 2021, Bloomberg reported that the smoke released by the fires contained high levels of lead and toxic medals and was deemed "a real health threat" to anyone — human or animal — living in or passing through the area.

There are a few answers to questions about what caused the fires, and for starters, climate change driven by human activities is credited for creating increasingly hot and dry conditions which are perfect for spreading wildfires. And spread the Camp Fire did: PBS says it reached a top speed of 80 football fields per minute.

There was more to it, and according to CNBC, the devastating Camp Fire was ultimately found to be caused by Pacific Gas & Electric transmission lines. PG&E admitted that it was "probable," but independent investigation says it's more than just probable. Investigators found that even though the median life expectancy for electrical transmission towers was 65 years, some of PG&E's towers were as much as 108 years old. The lines identified as the ones that started the fire were nearly 100 years old, and it was reported that PG&E could be liable for damages up to $30 billion.

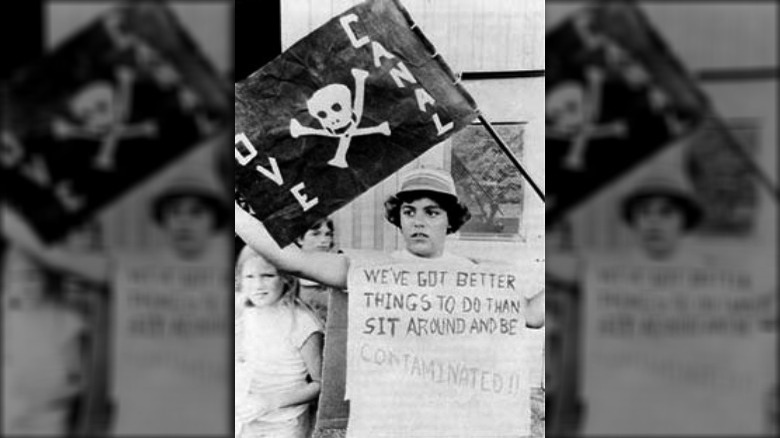

From dream community to suburban nightmare

In the early 20th century, William T. Love started building a community around a canal, dug between the Niagara Rivers with the goal of providing cheap power to those who lived nearby. It was a great idea, says the EPA, but once Tesla's alternating current became the go-to for transmitting electricity, the idea was suddenly outdated. In the 1920s, the canal was given new life: as a hazardous waste dump site.

Between 1942 and 1953, SUNY Geneseo says Hooker Chemical Company used the canal to dispose of about 21,000 tons of toxic waste, which was then covered. The resulting landfill was sold — for just $1 — to the city of Niagara Falls, which then used it to build a community, including homes and an elementary school.

Then, in 1978, a record rainfall and a series of events led to broken toxic waste drums working their way to the surface and leaking into the groundwater. Residents had no idea they were living on a toxic waste dump until they started seeing high rates of birth defects, leukemia, and other illnesses in their families — and their children started coming home with chemical burns on their skin. President Jimmy Carter declared a state of emergency, and within two years, U.S. legislators established the Superfund program to deal with situations just like this one.

When PBS looked into the state of Love Canal in 2018, they found some of the area had been redone, renamed Black Creek, and was separated from the still-uninhabitable area by a street.

The 87-day tragedy

On April 20, 2010, the crew of the Deepwater Horizon oil rig was getting ready to head out ... and then, it exploded. What followed was an 87-day ecological disaster that saw more than 3 million barrels of oil dumped into the Gulf of Mexico, and Live Science says it became the largest marine oil spill in the nation's history.

To put it in some context, the amount of oil spilled into the Gulf was about the same as half of the United States' daily oil production at the time. Eleven people were killed at the time of the explosion, and the cost in terms of marine life was devastating. At least 14,000 sea turtles — including hatchlings — perished, and that's just one species: Ecologists say that the oil spill touched every plant and animal living there, from fish, dolphins, and whales to the microalgae that forms the very bottom of the food chain. Gulf coast fisheries saw a decrease in jobs of about 25,000, and the tourism industry was devastated.

When the legal dust settled, BP paid out $20.6 billion over lawsuits and cleanup. Investigation, says New Scientist, pinned the blame squarely on human error and oversight at eight different points, including the use of improperly formulated cement, valve failures, test results that were misinterpreted, leaks that were overlooked, and several system failures. The cost was catastrophic.

The town covered in a snowfall of asbestos

The medical field has known for a long time — since 1924 — that asbestos brought a whole host of health problems with it. The Asbestos Network says that health issues were well-documented into the 1930s and '40s, and that's what makes the tragedy of Libby, Montana, so unthinkable.

Libby, says the Great Falls Tribune, has the highest rate of asbestos-related disease and mortality in the country, and that's true even though no one knows how many people really died of it.

The EPA says that the Zonolite Company started mining vermiculite in the 1920s, a process that continued with W.R. Grace's 1963 purchase of the mines. Up until the mine's closure in 1990, it was estimated that the town produced around 80% of the world's vermiculite, but there was a major catch: It was contaminated with asbestos. It wasn't until 1999 that the EPA responded to chronic health complaints, and by the time they investigated, asbestos was in everything from the air and soil to animal and human tissues.

People had been dying all along, and given that most died in a hospital overseen and ultimately controlled by the same W.R. Grace, it's not surprising that no one officially died of asbestos. Unofficially ... that's another story. Although the EPA says they finished their cleanup in 2018, those who live there say their friends and family are still dying.

The fires of October 1871

During the week of October 8, 1871, four major fires devastated areas around the Great Lakes. The most famous is the Great Chicago Fire, which destroyed a good part of the city, killed around 300 people, caused $3.7 billion in damages (in today's money), and left 100,000 homeless.

Less famous but more deadly was the Peshtigo fire, which happened on the same day. That one swept through Wisconsin, destroyed roughly 1.2 million acres of land, and killed around 2,500 people. Earth Magazine says that the same week, Holland and Manistee, Michigan, were also consumed by fire. Bad luck? Not quite.

At the time, the rich landscape was home to one of the nation's most valuable resources — a seemingly inexhaustible wealth of lumber. Loggers and farmers, attracted by the rich soils left behind by ancient glaciers, moved through in a way that made fire inevitable. When 1871 had a particularly dry summer, there was a lot to dry out. Fallen pine trees and needles covered the area, sawmills spat out an unthinkable amount of highly flammable sawdust, and then there were the mills, railroads, and furniture companies that were filled with glue, paint, and other chemicals just waiting for a spark.

Experts suggest smaller fires set by farmers to clear agricultural land were fanned by winds and combined into something apocalyptic: Witness reported flames nearly half a mile high, while today's experts estimate temperatures would have reached more than 1,800 degrees Fahrenheit, and winds were up to 100 mph.

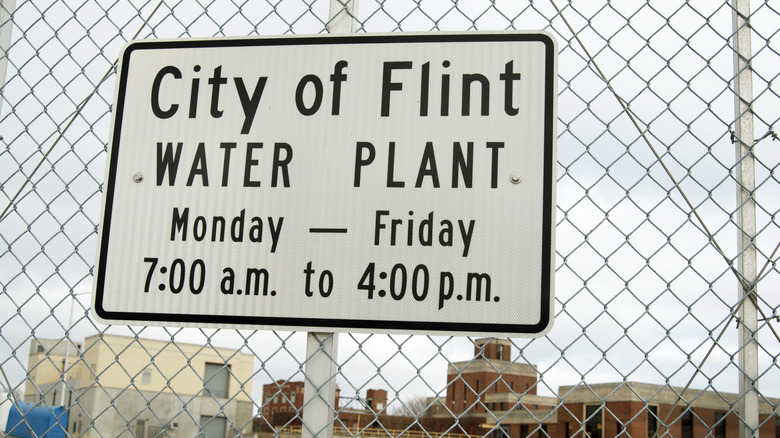

Safe, clean drinking water should be a basic human right. Right?

Flint, Michigan was once the bee's knees — at about the time it was cool to say things like "the bee's knees." That all came crashing down with a series of events that kicked off with the 1980s downsizing of one of Flint's biggest employers, General Motors.

According to CNN, it wasn't until 2011 that the state took control of Flint finances, and as part of the cost-cutting measures, there was a major change to their water supply. While a new pipeline was in the, well, pipeline, water was going to come from the Flint River in the meantime — and that was a terrible idea.

The switch happened in 2014, and in 2015, the EPA got involved to confirm high levels of lead pouring from citizen's taps due to the corrosion of the water pipes. The Natural Resources Defense Council says early signs that there was something very wrong included bad smells, rashes, skin ailments, and hair loss, but that was just the beginning. An estimated 9,000 children alone were exposed to high lead levels for at least 18 months, and pediatricians found these children to have levels of lead in their systems that had doubled or even tripled. Illness like Legionnaires' disease and the presence of other cancer-causing toxins surfaced as the problem continued to snowball, leaving Flint residents looking for answers.