The Real Reason This Buddhist Monk Set Himself On Fire

The image of Thích Quảng Đức's self-immolation may be one of the most well-known photographs in history. But the reasons behind Thích Quảng Đức's self-immolation have become hazy, with some misremembering his act as a protest against the Vietnam War, while others attribute it to anti-South Vietnam sentiments.

Although little changed in the immediate aftermath of Thích Quảng Đức's self-immolation, the match he dropped on himself would ignite the tinderbox that would ultimately lead to the 1963 South Vietnamese coup and the execution of President Ngô Đình Diệm and his brother, Ngô Đình Nhu.

Many would later follow in Thích Quảng Đức's image and set themselves on fire as a protest against the Vietnam War, but these self-immolations actually occurred in the United States, rather than Vietnam. The self-immolations in Vietnam during the Vietnam War, those of Quảng Đức and the many Buddhists who followed suit, were instead used as a protest against the South Vietnamese regime that was violently repressing and discriminating against Buddhists in Vietnam. This is the real reason this Buddhist monk set himself on fire.

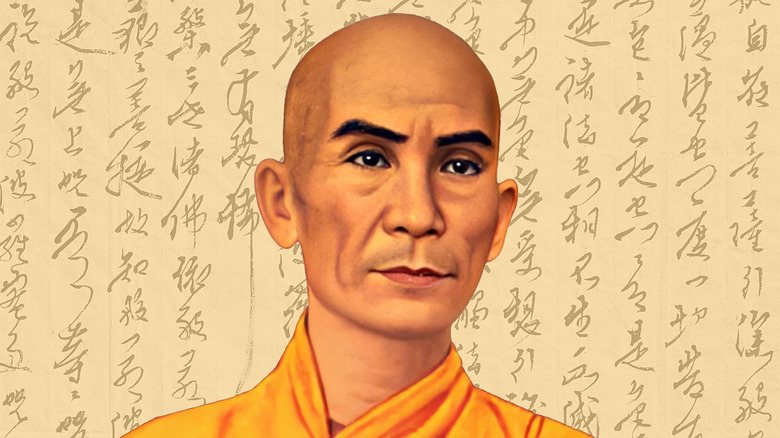

Who was Thích Quảng Đức?

Thích Quảng Đức (釋廣德) was born Lâm Văn Tức in the Khánh Hòa province of Vietnam in 1897, what was then considered the Indochinese Union. At the age of 7, Quảng Đức left his home to study Buddhism under the tutelage of his uncle, monk Thich Hoang Tham, according to the Smart Local. During this time, Quảng Đức adopted the name Nguyen Van Khiet. But once he became a monk at the age of 20, he adopted the dharma name Thích Quảng Đức.

In "The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism," Robert E. Buswell Jr. and Donald S. Lopez Jr. write that after becoming a monk, Thích Quảng Đức went to Mount Ninh Hòa and survived by living off alms for five years. It's unclear what happened in between, but by 1932, Thích Quảng Đức was invited to teach for the An Nam Association of Buddhist studies, where he taught for two years.

After moving to South Vietnam in 1934, Thích Quảng Đức travelled around the provinces. At one point, he moved to Cambodia for three years, where he studied Pāli literature and rebuilt Buddhist temples. He'd continue this work of rebuilding temples in Vietnam as well. In his life, Thích Quảng Đức assisted with the construction of up to 30 pagodas. The Quán Thê Âm Temple in Gia Định was the last temple that he worked on.

Who was Ngô Đình Diệm?

Ngô Đình Diệm was born on January 3, 1901 to an influential Catholic family. According to Vietnam's Lost Revolution by Geoffrey C. Stewart, he initially wanted to dedicate his life to Catholicism, but he decided instead to go into civil service due to the inflexibility of religious life.

By the age of 28, Diệm was a provincial governor, and he was Minister of the Interior within four years. But, according to Time, after Diệm demanded more political autonomy for the Vietnamese government from the French colonial government and the French refused, he resigned in protest.

During World War II, Diệm maintained his opposition to the French, and after the war ended, he also rejected joining Hồ Chí Minh and the Việt Minh. After continuing to speak out against both sides, Ngô Đình Diệm left Vietnam in a self-imposed exile and traveled to several countries, including the United States. There, he tried to rally support for anti-colonialism and anti-communism, and he caught the attention of several U.S. officials.

By 1954, Diệm's brother, Ngô Đình Nhu, convinced Emperor Bảo Đại to put Diệm in a position of power. Diệm returned from his self-imposed exile in June 1954, and within two weeks he'd accepted the post of prime minister of the State of Vietnam and created his new government, according to The Vietnamese.

The Huế Phật Đản shootings

When the Vietnam War broke out in 1955, Ngô Đình Diệm, who was now President of South Vietnam, maintained his regime with the support of the United States. And according to History Net, during his reign, Diệm consolidated power among Catholics and began persecuting Buddhists.

In "The Pentagon Papers," Daniel Ellsberg writes that Diệm's repressive actions against Buddhists came to a head on May 8, 1963 during a protest in Huế, South Vietnam. The previous day, police had invoked a law that forbade displaying religious flags, but Buddhist flags were the only ones that were targeted. On May 8, the day that the birthday of the Buddha fell on that year, after having seen Catholic flags being previously flown for the archbishop, Buddhists in Huế began waving their own Buddhist flags in protest.

Up to 3,000 Buddhists joined the protest, and by evening they were rallying at the local radio station. But according to "Descending Dragon, Rising Tiger" by Vu Hong Lien and Peter Sharrock, when the unarmed protesters refused commands to disperse, the police and the military fired into the crowd. The Global Nonviolent Action Database writes that "Stun weapons and fire-hoses [also] were used."

14 people were injured and nine killed, including children. Although communists were quickly blamed for the incident, the following day upwards of 10,000 people showed up to protest the killings committed by the government. Student protestors chanted "Down with Catholicism" and "Down with Diệm government."

Protests by Buddhists

Over the following seven months, the protests led primarily by the Buddhist monks became known as the Buddhist crisis. President Ngô Đình Diệm met with representatives of the Buddhist community on May 15, 1963, having been pressured to negotiate by the Kennedy administration, but refused to make any changes.

In "A Cruel Theatre of Self-Immolations," Grzegorz Ziółkowski writes that Diệm rejected all of the demands of the Buddhist community, including refusing to end the mass arrests and harassment against the Buddhist community or "providing redress to victims of the Hue massacre."

Meanwhile, the Buddhist community began hunger strikes in Huế and Ho Chi Minh City — then Saigon — and held demonstrations. On June 3, Huế witnessed another violent repression when security forces "unleashed a chemical attack against a 1,200-strong student protest." At least 67 people were injured in the chemical attack.

In response to the abuse that protestors were receiving and the continued repression of religious freedoms, Buddhists at the Từ Đàm pagoda in Huế also initiated a hunger strike. The city declared a state of emergency, and the temple was surrounded by barbed wire by government security forces, "refusing access even to medical service," in a blockade that lasted until June 10.

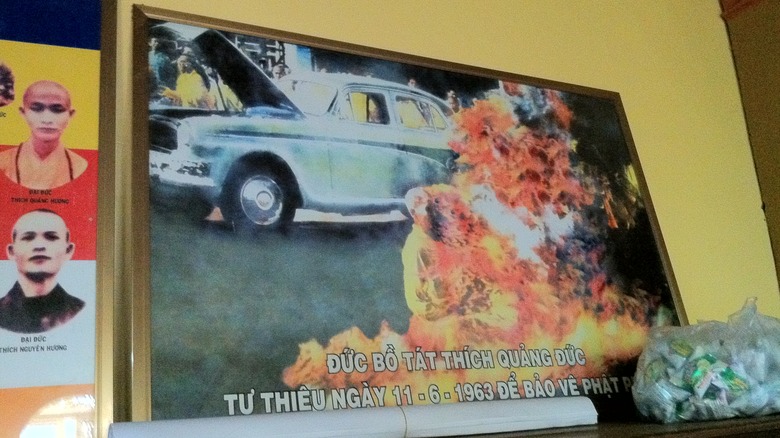

Thích Quảng Đức's self-immolation

On June 10, the hunger strike at Tu Dam pagoda ended and the Buddhists and security forces left. The Global Nonviolent Action Database writes that this created "the appearance of peace." But the following morning, one of the most unforgettable acts of protest was witnessed in downtown Saigon.

Along with upwards of 350 monks and nuns, Thích Quảng Đức went to the middle of a busy intersection. The Vietnamese writes that after forming a circle around the sitting Thích Quảng Đức, one monk poured gasoline over him while another handed him matches.

Covered in gasoline, Thích Quảng Đức chanted a prayer to Amitābha Buddha, according to All That's Interesting. At the moment that he finished the prayer, he lit the match and dropped it onto himself.

In "The Making of a Quagmire," David Halberstam describes witnessing the scene: "Flames were coming from a human being; his body was slowly withering and shriveling up, his head blackening and charring. In the air was the smell of burning flesh [...] As he burned he never moved a muscle, never uttered a sound, his outward composure in sharp contrast to the wailing people around him."

Amid cries and screams, a monk repeated "calmly" with a microphone, in both Vietnamese and English, "A Buddhist priest burns himself to death! A Buddhist priest becomes a martyr!"

Why did Thích Quảng Đức do it?

Although his protest was in response to the Diệm regime's repression and discrimination of Buddhism, Thích Quảng Đức's self-immolation was neither anti-South Vietnam nor pro-North Vietnam. According to The Vietnamese, the political beliefs for many Buddhists in Vietnam was aligned with Chấn Hưng Phật Giáo, also known as Buddhist revival. "Under the belief of Buddhist revival, many monks and Buddhists subscribed to a particular Vietnamese-Buddhist nationalism, which saw Buddhism as the national religion and the only path to Vietnam's future prosperity." This is also believed to have influenced Thích Quảng Đức's decision to self-immolate.

Thích Quảng Đức also left a letter detailing his departure: "Before closing my eyes and moving towards the vision of the Buddha, I respectfully plead to President Ngo Dinh Diem to take a mind of compassion towards the people of the nation and implement religious equality to maintain the strength of the homeland eternally. I call the venerables, reverends, members of the sangha and the lay Buddhists to organize in solidarity to make sacrifices to protect Buddhism."

Thích Quảng Đức called it a "donation to the struggle," and ultimately, self-immolation was an established practice in Mahayana Buddhism, even if it was controversial, writes Michael Biggs in "Dying for a cause—alone?" And Thích Quảng Đức wasn't operating in a vacuum. He understood the influence that media had, and the day before the self-immolation, the Associated Press heard that "something important" was going to happen.

President Ngô Đình Diệm's reaction

When President Ngô Đình Diệm heard about Thích Quảng Đức's self-immolation, he struggled to do some damage control. STSTW Media writes that later that night on June 11, Diệm addressed the nation with a radio broadcast, claiming that he was "disturbed by the self-immolation as everyone else in the country" and promising to investigate and reform the issues that Buddhists were protesting over.

However, few believed his statement. And comments from Diệm's family members seemed to make it clear that they cared little about the Buddhists' concerns. According to All That's Interesting, his sister-in-law, Trần Lệ Xuân, told the New York Times that she would "clap hands at seeing another barbecue show." Although it's unclear if she actually made such a statement, she did refer to the self-immolation as a barbecue in an interview with CBS News, and claimed that "Even that barbecuing was done not even with self-sufficient means because they used imported gasoline," writes Ziółkowski in "A Cruel Theatre of Self-Immolations."

But Diệm's regime was fading, and as the repression continued, nationalists led by General Duong Van Minh began plotting a coup. The CIA approved of this coup, especially since the Kennedy administration at the time was discouraged by Diệm's inability to manage the Buddhist crisis. For the United States government, anything that the communists could use as propaganda was bad news, according to NPR, and they were willing to encourage any regime change that could benefit them.

The American response

Malcolm Browne, a journalist and photographer from Associated Press, witnessed and documented Thích Quảng Đức's self-immolation. Within 15 hours, his photograph was being featured on the front pages of newspapers across the world.

Upon seeing the photograph, President John F. Kennedy's only words were "Jesus Christ!" and some reports claim that he immediately left the room. According to "America's Miracle Man in Vietnam" by Seth Jacobs, Kennedy later said to Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge that "no news picture in history has generated so much emotion around the world as that one."

Considering the photographs that would come out of the Vietnam War, it's clear that this photograph was just the start. But with it, the Kennedy administration put more pressure on President Ngô Đình Diệm to come to an agreement with the Buddhist community. Secretary of State Dean Rusk even threatened to publicly denounce Diệm if he didn't meet the demands of the Buddhists. As a result, Diệm and Buddhist leadership ended up signing the Joint Communiqué.

Signing the Joint Communiqué

On June 16, 1963, President Ngô Đình Diệm signed a Joint Communiqué with Buddhist leadership, in which he agreed to meet five of the demands of the Buddhist community. However, according to the Report of the United Nations Fact-Finding Mission to South Vietnam, it became clear almost immediately that Diệm wasn't planning to uphold the promises made in the Joint Communiqué.

Government agents soon launched a campaign to convince people that the protests were inspired by communists, and even the agreement to allow the display of the Buddhist flag was ignored, instead "permitt[ing] [the flag] only on buildings belonging to the General Buddhist Association and not in other places." Travel restrictions were also placed on Buddhist monks, and monks who had been arrested for supporting the demands of the Joint Communiqué, numbering up to 30, continued to be imprisoned.

STSTW Media also notes that the Times of Vietnam, which was used as a mouthpiece by the Diệm regime, claimed that journalists and monks were "colluding to destroy the Vietnamese government." Those who were released were forced to sign documents beforehand. By mid-July, peaceful protests by Buddhist monks were once again being violently suppressed.

More self-immolations

Thích Quảng Đức wasn't the only Buddhist to self-immolate in protest, and many monks and nuns followed his example. Between August and October 1963, at least five Buddhist monks in Vietnam also self-immolated in protest against the persecution of Buddhists. According to "The Self-Immolators" by Day Blakely Donaldson, among the monks who self-immolated were Thích Nguyên Hương, Thích Thanh Tucd, and Thích Tieu.

In "A Cruel Theatre of Self-Immolations," Ziółkowski writes although Thích Tịnh Khiết, one of figures of Buddhist leadership, forbade self-immolations "unless necessary," after the self-immolation of 23 year old Thích Nguyên Hương, the ban was ignored. In August 1963, at least three self-immolations occurred.

Buddhist nuns and other women were also part of the self-immolation protests, including Diet Quảng, Thích Nữ Thanh Quang, Ho Thi Thieu, Thich Nu Vinh Ngoc, and Nguyen Thi Van, among others. Self-immolations by Buddhist women also continued throughout the 1970s, writes Robert Topmiller in "Struggling for Peace."

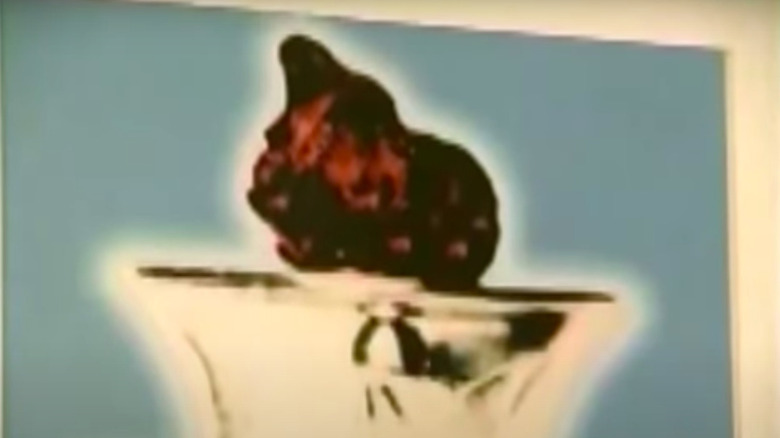

The heart of Thích Quảng Đức

After Thích Quảng Đức self-immolated and the fire died out, his body was covered with yellow robes and carried to a temple. He had arrived with over 300 people, but as his body was taken back, over 1,000 people followed the procession. Thích Quảng Đức was re-cremated during the funeral, but the story is that his heart remained intact even after the second burning. Rare Historical Photo writes that as a result, his heart was considered to be a holy relic and kept at Xá Lợi Pagoda in a glass chalice.

But, according to "A Cruel Theatre of Self-Immolations," even his heart wouldn't be given a chance to rest. Buddhist shrines were raided and looted by ARVN Special Forces on August 21, 1963, and Xá Lợi Pagoda was specifically targeted and Thích Quảng Đức's heart was confiscated by soldiers. Although soldiers also tried to steal his ashes, Thích Trí Quang and another monk kept the urn containing them safe, and were able to find refuge in the nearby U.S. Operations Mission building.

President Ngô Đình Diệm justified the raids, which led to the deaths of at least 30 monks, by claiming that the Viet Cong was using Buddhist temples as sanctuaries, alleging a Communist-Buddhist conspiracy.

American imitations of Thích Quảng Đức's self-immolation

Buddhist monks and nuns weren't the only ones who followed Thích Quảng Đức's example. Several Americans also self-immolated themselves in the months following as an act of protest, this time against the Vietnam War itself.

The first American known to have self-immolated in response to the Vietnam War was Alice Herz. A German-born U.S peace activist, Herz self-immolated on March 16, 1965 on a street in Detroit, feeling that all the traditional methods of protesting were having no effect. She wrote to her friends "I choose the illuminating death of a Buddhist to protest against a great country trying to wipe out a small country for no reason," according to The Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War.

The Guardian reports that Baltimore Quaker Norman Morrison followed suit on November 2, 1965, setting himself on fire 40 feet from the window of wartime Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara outside the Pentagon. He had also brought his baby daughter Emily with him, but did not involve her in the self-immolation.

Among the other Americans who self-immolated in protest against the Vietnam War were Hiroko Hayasaki, Roger LaPorte, Erik Thoen, Florence Beaumont, George Winne, and Ronald Brazee, according to "They Who Burned Themselves for Peace: Quaker and Buddhist Self-Immolators during the Vietnam War."