The Hidden Detail About The Statue Of Liberty You Never Knew About

The Statue of Liberty (officially named Liberty Enlightening the World) has all sorts of well-known and relatively obvious symbolism included in its design. As reported by Boredom Therapy there are the seven points of the crown, representing both the seven continents and seven seas; the torch lighting the way; the fact that she faces southeast, the direction of most arriving ships, in order to welcome those sailing into New York Harbor; the tablet in the left hand inscribed with the Roman numerals for July 4, 1776; and the broken shackle cuffs on the ankles as well as broken chains around the feet, representing freedom. A lesser known fact about the broken chains is that not only do they represent the general concept of freedom, they were specifically meant as a symbol of abolition and a celebration of the 13th amendment to the United States Constitution — passed by the Senate in 1864, the House in early 1865, and ratified in late 1865 — which outlawed slavery.

The idea for the statue, which was presented to the United States as a gift from France, originated with French scholar and poet Édouard de Laboulaye in 1865. Laboulaye conceptualized a statue that would be a celebration of the 100th anniversary of the United States' independence from Great Britain. As he had no design experience, sculptor Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi stepped in, as did engineer Alexander Gustaf Eiffel (yes, as in the Tower).

The Statue of Liberty specifically celebrated abolition

Per the National Park Service, Laboulaye was an expert on the U.S. Constitution as well as a prominent anti-slavery activist who had supported President Abraham Lincoln and co-founded the French Anti-Slavery Society in 1865. As reported by Boredom Therapy, one foot of the Statue of Liberty is partially raised off the ground, as seen in the photo above. This was deliberate and goes with the other foot, surrounded by a broken chain and shackle, all serving as a symbol of Édouard de Laboulaye's pro-abolition beliefs as well as his protest against France's repressive inclinations. The National Park Service notes that Laboulaye hoped that France's gift would inspire French citizens to embrace democracy over the country's monarchy.

The statue and its symbolism have come to be associated with immigration rather than anti-slavery, particularly because of the famous immigrant inspection station at neighboring Ellis Island and the Emma Lazarus poem on a plaque at the base of the statue that begins, "Give me your tired, your poor, Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free." However, according to The Washington Post, Ellis Island didn't open until 1892, six years after the statue's unveiling, and the plaque wasn't added until 1903. History professor Edward Berenson told the Post, "One of the first meanings [of the statue] had to do with abolition, but it's a meaning that didn't stick."

Perhaps ironically (but not surprisingly), Laboulaye's tribute to abolition didn't resonate with many Black Americans.

'Shove the ... statue, torch and all, into the ocean'

Per the National Park Service, after the statue's unveiling in 1886, many Black newspapers pointed out the irony of the Statue of Liberty celebrating American freedom and democracy while racism and discrimination continued to run rampant in the United States after slavery was declared illegal. By 1886, Reconstruction had been destroyed, the Supreme Court had failed to uphold many laws guaranteeing civil rights for Black Americans, and racist Jim Crow laws were becoming more common throughout the southern United States. It's no wonder that many people saw the symbolism of the Statue of Liberty as cruelly ironic and hypocritical, espousing American ideals that weren't actually being honored and applied to all citizens.

An 1886 editorial in the Cleveland Gazette, quoted by The Washington Post, read in part, "Shove the ... statue, torch and all, into the ocean until the 'liberty' of this country is such as to make it possible for an industrious and inoffensive colored man in the South to earn a respectable living for himself and family ... The idea of the 'liberty' of this country 'enlightening the world' ... is ridiculous in the extreme."

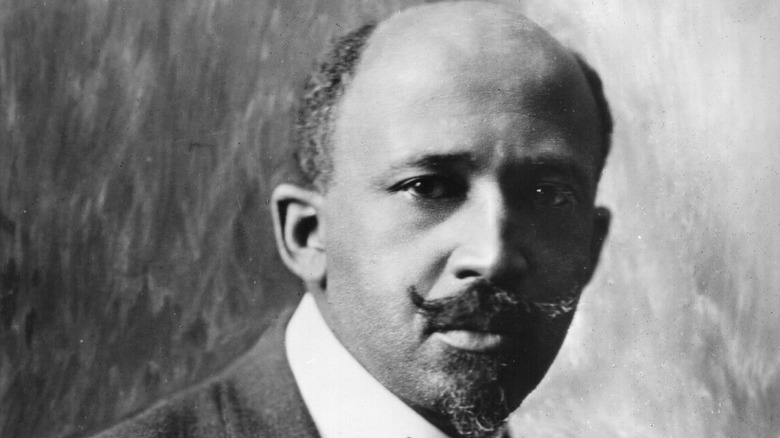

In his autobiography, sociologist, activist, and scholar W.E.B. Dubois (above) wrote of sailing into New York in 1894 after two years in Europe: "I know not what multitude of emotions surged in the others, but I had to recall [a] mischievous little French girl whose eyes twinkled as she said: 'Oh, yes, the Statue of Liberty! With its back toward America, and its face toward France!'"