The Only US President Who Was A Citizen Of The Confederacy

Given the massive influence that the Civil War had on American history overall and just how much people in the 21st century know about it — slavery, states' rights, all of that debate — it's a little strange to think that most people probably never consider that an eventual U.S. president might have once lived in the Confederacy. After all, there's the famous Confederate leadership — Confederate President Jefferson Davis or General Robert E. Lee, for example — but there's not a whole lot of discussion on just where U.S. and Confederate leadership and citizenship might've started overlapping.

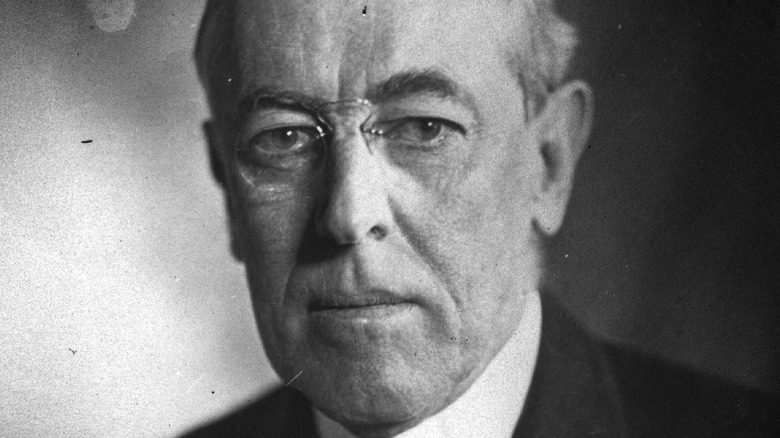

But just where is that overlap? Who's this one U.S. president who also happened to be a citizen of the Confederacy in his youth? Well, that would be Woodrow Wilson.

Yes, it's that President Wilson, the same man who's probably most known for leading the United States through World War I before proposing the idea for the League of Nations (the short-lived predecessor to the United Nations). He's got some pretty influential stuff on his resume, and the more positive ones are probably the things you had to learn back in your U.S. history class. But there's a side to Wilson's story that's far less talked about, because not only was he a citizen of the Confederacy, but he also definitely acted like one, harboring ideas on race that pretty much undid most of the progress brought by Reconstruction. It's not a pretty story, by any means.

Woodrow Wilson's upbringing and ideology

So, given that Woodrow Wilson was born in the South shortly before the Civil War, what was his childhood actually like? Wilson was born in December 1856, in Staunton, Virginia, though he moved around the South over the course of his youth, witnessing much of the destruction of the Civil War firsthand. As the Miller Center explains, he was raised the way you'd probably think a young kid in the Confederacy was raised: His father was a Presbyterian minister at a church that leased enslaved people, teaching his son that Southern secession was completely justified. He regularly preached in favor of slavery and also served in the Confederate army himself (via National Park Service).

As for what that did to Wilson's ideology? "Race and Nation in the Thought and Politics of Woodrow Wilson" explains that he wasn't a violent racist; he wasn't exactly in favor of lynching or terror. Instead, he represented a (relatively) moderate, Southern elite – the sorts of people who just thought of African Americans as inherently inferior and expected them to accept their lot in life. He even viewed slavery as a part of the "civilizing process" and regularly flew into a false rage with a Black servant, simply because he saw it as the "only way to deal with colored servants" (via "The Jim Crow Policies of Woodrow Wilson"). And that's just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to Wilson's view of race.

Segregation of the federal government

If you want the really short version of just why Woodrow Wilson was such a problem in the realm of civil rights, well, here you go. To put it simply, Wilson was responsible for bringing the segregation of the Jim Crow era to the federal level.

Due to the changes brought by Reconstruction, African Americans were given the opportunity to take part in the political playground of Washington, D.C. (via History). Despite local governments doing all they could to fight that change, at the federal level, Black voices were finally being heard.

But when Wilson arrived on the scene, both he and (purportedly) his wife were shocked by the integrated nature of the federal government, with Black and white employees working and eating together (via "The Jim Crow Policies of Woodrow Wilson"). So Wilson worked to roll back all of that progress. He started with the Post Office and the Treasury Department, which, according to Berkeley Haas, were two of the government departments with the highest numbers of Black employees; the Department of the Interior followed, and all three were home to segregated toilets before too long (via The Atlantic). Wilson's own cabinet followed the same pattern, segregated and led just about entirely by Southern Democrats. Black employees were, on the whole, barred from serving in respected federal positions; those who had already been on the job were demoted, and any Black applicants to these sorts of jobs just weren't even considered in the first place.

The economic effects of federal segregation

With the historic ruling in Brown v. Board of Education, it's been made abundantly clear that "separate is not equal" (via Smithsonian). That's true on a lot of fronts, but Woodrow Wilson's segregation of the federal government really makes that point even clearer when it comes to economics and finance.

Now, to be entirely transparent, even prior to Wilson, there had already been a wage gap between Black and white civil servants; according to Berkeley Haas, that deficit averaged about 37%, with that skew being largely due to the fact that Black employees held more of the lower-paying jobs. But when Wilson started making his changes, that gap grew immensely. Between 1913 and 1921, a comparison of Black and white employees in approximately equal jobs showed the wage gap increased by about 7% (which increased the overall wage gap by about 20%). And that's just the average. Though the exact numbers aren't exactly available, there's a good chance that number was even higher in particular departments that really committed to segregation. Berkeley Haas directly attributes that change to Wilson himself, maintaining that his influence can still be felt in economic disparities well into the 21st century.

Those economic changes also rippled outward in other meaningful ways. History adds that, during Reconstruction, Black homeownership in Washington, D.C., skyrocketed due to the availability of high-paying jobs for African Americans, but in the wake of Wilson's policies, those numbers plummeted back down.

He believed segregation was beneficial

During his presidency, Woodrow Wilson made some pretty uncomfortable statements in order to justify segregation. Well, more than "pretty uncomfortable." More like "completely unacceptable."

In effect, he saw federal segregation as a beneficial thing for everyone involved. Per The Atlantic, he didn't institute segregation to "put the Negro employees at a disadvantage," but rather to "prevent any kind of friction between the white employees and the Negro employees." It sounds a whole lot like that "separate but equal" argument that's long been associated with the Jim Crow era, which just about says it all. But he even doubled down on that argument, going so far as to claim that segregation was definitely beneficial for African American employees; according to "The Jim Crow Policies of Woodrow Wilson," he believed that workplace segregation would mean that Black workers would be "safe in their possession of office and less likely to be discriminated against." You know, as a result of the inherently discriminatory process of segregation.

And if that wasn't enough for you, he also threw his gross racial stereotypes into the mix, disliking, on principle, the idea of white women working in the same spaces as Black men – yet another reason to segregate the federal government, apparently.

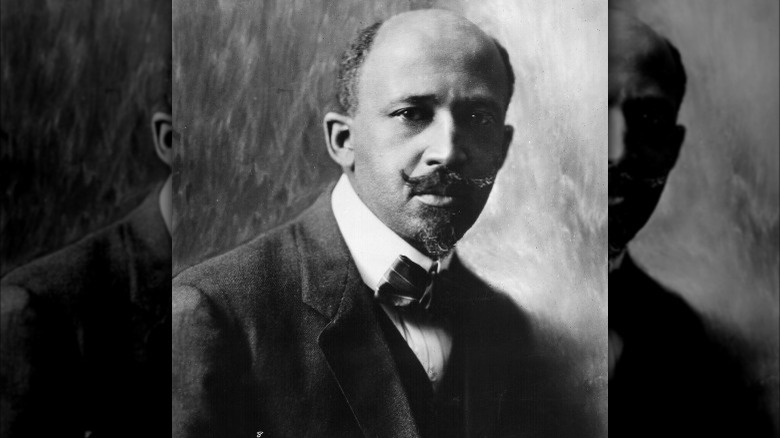

Woodrow Wilson tried to vehemently defend his decisions

While all the policies of federal segregation instituted by Woodrow Wilson were terrible, nothing quite illustrates just how racist Wilson was more than his own words. In response to Wilson's policies, leaders of African American communities spoke out. W.E.B. Du Bois wrote that it seemed like white politicians thought their Black coworkers were "contaminated" and asked, "How long will it be before the hateful epithets of 'N*****' and 'Jim Crow' are openly applied?" (via Thirteen). William Monroe Trotter even took a group to visit the president in person, telling him that he was "disappointed" that Wilson apparently didn't see anything wrong with the situation (via The Atlantic).

The conversation that followed did not go well. Wilson started by claiming that the discrimination really wasn't that bad, and there hadn't been that many changes to working conditions (via "The Jim Crow Policies of Woodrow Wilson"). He also blamed African American leaders for bringing any attention to segregation at all, saying they were reading too far into the situation and that doing so would cause further problems. When Trotter tried to object, Wilson ignored him, then said he wouldn't be welcomed back to the White House. He even implied that Trotter could learn from the colleagues who had come with him and said nothing; Wilson just wanted silent compliance, really.

And in the aftermath of all that? Wilson did regret how everything went, but not the way you'd hope. He was only disappointed that he'd lost his temper, saying that he should've listened and nodded until the group decided to leave. No regrets about the racism, though.

He had initially promised progress

In the aftermath of the Civil War, the political scene was pretty clearly and obviously split; in a general sense, the Democratic South was still holding onto all of those antebellum ideas, while the Republican Party was the one spearheading Reconstruction. With that in mind, it makes a good deal of sense that Black citizens tended to side with and vote for Republican politicians (via Berkeley Haas). But Woodrow Wilson was actually a bit of an exception to that.

At the time, the view of the Republican presidential candidates wasn't especially great; to a lot of African American voters, Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft just weren't cutting it (via "The Jim Crow Policies of Woodrow Wilson"). So in response (and, maybe, just kind of in protest), many ended up turning to the Democratic party instead, throwing their support behind Wilson. And this didn't come solely out of the negativity felt toward the Republican party. Wilson actually did manage to gain the trust of some pretty big names, promising African Americans that they could "count upon [him] for absolute fair dealing" when it came to their rights. W.E.B Du Bois (pictured above) actually called Wilson a "cultivated scholar" of "farsighted fairness" – decently high praise. Du Bois went on further to say that he was certain Wilson would not "seek further means of 'Jim Crow' insult."

Oh, the irony of that. By the time Wilson was president, other leaders of African American communities would come to see his actions as a betrayal, even feeling that they, themselves, had betrayed their own communities by trusting him (via The Atlantic).

He'd already started instituting segregation before his presidency

While Woodrow Wilson's presidency was filled with instances of racism and segregation, the unfortunate thing is that none of this was really new ground for Wilson. In some ways, he'd already had practice at making discrimination the norm at an administrative level.

Prior to his time as United States president, Wilson also served as the president for his alma mater, Princeton University. By the time of Wilson's leadership, Princeton had begun integrating its student population; it wasn't a fast process, by any means, and was riddled with controversy, but it was a small step in the direction of progress.

But then Wilson arrived on the scene, determined to change all of that. According to History, he began denying students entry to the school based on race — Black students were being clearly segregated against. But potentially more egregious was the fact that he attempted to rewrite the history of the university, pretending that Black students had never attended. This despite the fact that he was a Princeton student when a Black student was admitted, a professor at the time a Black graduate student was admitted, and the university's president when two Black students earned degrees. Still, he claimed that "the whole temper and tradition of the place are such that no negro has ever applied for admission" as a way to justify his discriminatory policies (via Princeton & Slavery). He even tried to solidify his stance further, saying, "It is altogether inadvisable for a colored man to enter Princeton."

Woodrow Wilson wrote a book idealizing the Confederate South

Woodrow Wilson was really quite the academic. And like any good scholar, he used all of that university education to get some academic writing under his belt. Actually, he wrote a whole textbook, but, well, the contents of that book are definitely a bit questionable. The textbook in question: "A History of the American People." In it, Wilson walks through the events leading up to Reconstruction, saying that the abolition of slavery left African Americans "pitiable" and helpless, armed with "the inexperience of children." He saw abolition as the guilty party, because now these "weak and incompetent" African Americans were without their "strong and capable" white masters. It's not a great look, and that just comes from a single paragraph.

At other points, Wilson also discusses the Reconstruction-era Ku Klux Klan, and he sounds rather enchanted by them. He shrouds them in entrancing mysticism; you'd think you were reading some sort of adventure novel with the KKK as the mysterious vigilante. They appeared like ghosts, bringing with them the "delightful discovery of the thrill of awesome fear," existing to "protect the southern country." And Wilson goes further to diminish the justified panic African Americans felt at seeing the KKK approach; verbatim, he calls it a "comic fear."

Really, he just wasn't a fan of Reconstruction, on the whole, calling it a "burden ... sustained by the votes of ignorant negroes" and saying that Southern resistance to it was simply the "mere instinct of self-preservation."

His preferred form of entertainment

Racism is not entertaining. That's the kind of thing that should be hard to argue against. But when it comes to Woodrow Wilson during his presidency in the 1910s, well, things were a little different. Or a lot different. See, "The Jim Crow Policies of Woodrow Wilson" mentions that one of the ways that Wilson would entertain his (pro-segregation) staff was to tell "darky stories" during meetings, and you can rest assured that those stories did not portray African Americans in a very positive light.

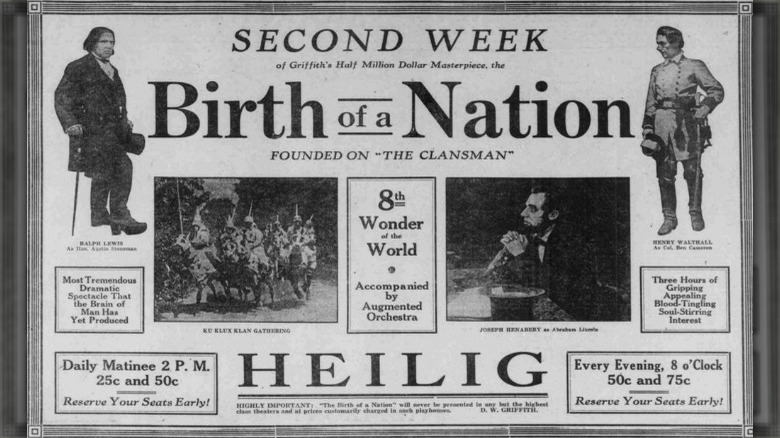

But things didn't end there. Wilson was a pretty big fan of the movie "The Birth of a Nation." The problem with that? Well, NPR calls the movie "three hours of racist propaganda," which explains the issue succinctly. As for the long version: the movie goes to great lengths to vilify African Americans, portraying them as predatory (and using a bunch of white actors in blackface). Yeah, it's not great.

And Wilson decided to air it at the White House, even inviting a bunch of families to see the film that he claimed was "history written with lightning." The vilification of the progressive changes of Reconstruction, the apparently heroic acts of the KKK – Wilson claimed it was "all too true." But, then again, maybe it's no surprise that he had such a penchant for the film; his own textbook was quoted in the movie's opening, after all (via History).

Maybe he just didn't stand a chance?

So, let's get this straight really quick. All of the discriminatory policies and federal segregation by race was incredibly problematic, reversing a lot of the social progress that had finally occurred through the decades prior. And the fact that Woodrow Wilson often didn't seem all that bothered by what he did is something that definitely should be recognized. That said, there were a few times where he seemed to change his tune, if only a little.

According to "The Jim Crow Policies of Woodrow Wilson," partway through Wilson's presidency, the country saw the outbreak of more than a handful of really bloody race riots. The situation had turned dire, and it seemed that Wilson finally started to realize that, just maybe, segregation wasn't the best way to go. When asked by NAACP representatives to do something, speak out, take action, Wilson only felt that he wouldn't be able to make any sort of change, eventually agreeing to the vague promise that he would "seek an opportunity" to make a statement. It was hardly a committed or reassuring response, but even those representatives who had gone to speak with him felt that their "hostility toward Mr. Wilson [was] greatly shaken," finding him rather defeated by the entire situation.

Prior to that meeting, he'd even stated that he just didn't see any way for him to reverse racial tensions and segregation (although that still doesn't absolve him of the policies he enacted while in office).

People are questioning his legacy

The teardown of Confederate monuments has been a pretty hot topic of conversation, what with groups of Confederate descendants arguing for their preservation, while many others argue that these monuments memorialize years of racism and discrimination (via NPR). So, with that in mind, where does the one Confederate-raised president fall in this kind of light? After all, he is a United States president; he has his own fair share of memorials and buildings that bear his name.

Well, Princeton University – Wilson's alma mater – has cast its vote. According to The Guardian, Princeton has acknowledged that Wilson did good for the school, upgrading both their physical facilities and standards for education, while being remembered for his impressive political skills. But the less-than-glamorous parts of his leadership really needed to be reckoned with, and that included voting to have his name removed from their School of Public and International Affairs.

All of that came about years after student activists had protested his name remaining on their campus building but was further kicked into gear by the killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and others. Spokespeople for the university explained that they questioned whether or not it was right for their "school of public affairs to bear the name of a racist who segregated the nation's civil service," though they also made it clear that this was just one small (but important) step in the process of dealing with "the realities and legacy of racism."