Weirdest Made-Up Medical Conditions

Talking about medical conditions can be terrifying. There's no shortage of horrible diseases you can develop, and there's plenty of disfiguring, painful ways you can suffer before dying a horrible death. We're not here to talk about those things. We're here to talk about the insane, stupid, and absurd diseases you won't believe people actually worried about, and we can guarantee you'll never develop any of them. Why? Because they're all completely fictitious, made up by people who needed to further their own agenda for reasons that are diabolical, selfish, and in one case, noble.

Bicycle face was a great excuse not to exercise

If you're going to come up with a condition that's meant to terrify the bejesus out of people, at least come up with a great name. Bicycle face might be completely lacking in that department, and you can thank—we think—a British doctor named A. Shadwell for his lack of creativity.

Shadwell had other things on his mind, though, and that was coming up with a condition to discourage women from hopping on these new-fangled gizmos called bicycles and pedaling their way to independence. The advent of the bicycle allowed women new freedoms, encouraged physical activity, and even changed the way they dressed, and clearly, the world couldn't be having any of that nonsense.

According to Vox, male doctors spent a good part of the 1890s preaching about bicycle face. The condition was characterized (variously) by a flushed or pale face, a perpetually drawn and exhausted expression, dark shadows, a clenched jaw, and bulging eyes. Causes varied, and while some doctors claimed it was the physical effort of riding or balancing a bike, others said it was brought down by a God that's mad at people for violating the Sabbath. By the end of the decade, some revolutionary free-thinkers were writing about how bicycle face wasn't as much of a thing as they'd been claiming after all, but rumors continued for decades afterwards. Women still pedaled away, bulging eyes be damned.

Halitosis was a marketing stunt

If you've ever bought any product that advertises it's only purpose is to make your breath fresher, then congratulations, you've bought into a made-up medical condition. Let's go back to the 1880s for this one, and the invention of Listerine. At the time, it was a prescription medication used to prevent infections from developing in wounds. If you've ever had a tooth pulled, you know how difficult it can be to keep infection out of your mouth, and it turned out Listerine was great at it.

According to io9, that's when things started to get a bit out of hand. Listerine's owners wanted to sell more product, and that's legit. What's not legit is that they invented a disease called halitosis, and lauded their product as the cure.

Halitosis wasn't just bad breath, it was a Condition with a capital "C". The only way to fight it—and avoid any social embarrassments that went along with it—was to use some wound antiseptic in your mouth. People did, and before you laugh, remember we still do. That's marketing genius.

Overactive bladder made people money

Buying into made-up medical conditions isn't just something our silly ancestors did, either. Let's try an experiment—all you need to do is think about how often you find yourself heading off for a bathroom break. We're not talking about the ones you go on to get away from work, we're talking about a legitimate need to pee. Three times a day? Four? Twelve? In 2001, the answers people gave during a telephone survey helped create a condition called overactive bladder and, at the time, about 33 million Americans were diagnosed with it.

Who's doing this diagnosing, you might ask. According to the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, the condition was defined by two university urologists, and then presented at medical conferences sponsored by the drug companies pushing their cures for overactive bladder. Convenient, right?

This isn't just a harmless push to sell some pills, either. Investigations have found the drugs prescribed to treat overactive bladder have been linked to almost 200 deaths between 2013 and 2016, and that's insane. The FDA has gotten more than 12,000 complaints about the drugs, and seriously—if you find yourself needing to pee a lot, just think of it as a legitimate excuse to get away from your desk for a few minutes.

Drapetomania was so racist

Let's apologize straight away, because this is going to get a little offensive. What else would you expect, though, from a condition invented to explain why a slave would want to run away from his or her master?

It was called drapetomania, and PBS says it was defined by Dr. Samuel Cartwright from the University of Louisiana. When he wrote up his 19th century profile of drapetomania, he called it "a disease of the mind" that was easily avoidable and curable if plantation owners and overseers would just treat their slaves in the way God wanted. That involved kindness...but not too much kindness, and definitely not letting them think they were equals—that was just asking for problems. Warning signs that a slave was developing a case of drapetomania included a "sulky and dissatisfied" personality, and if your slave was that, he or she was slipping into what Cartwright called "the negro consumption."

Whatever you do, he said, you probably shouldn't try to whip it out of them. Instead, treat your slave kindly, give them clothes, fuel for a fire, and allow each family their own home. He then claimed they'll "fall into that submissive state which it was intended for them to occupy in all after-time." And that all proves just because something is tradition, that doesn't make it right.

Dysaethesia Aethiopica was even worse

Good ol' Dr. Samuel Cartwright took a shot at creating another medical condition to explain why a slave might want to cause trouble for his owners, too, and he called this one dysaethesia aethiopica. According to his article "Diseases and Peculiarities of the Negro Race" (via PBS), dysaethesia aethiopica was characterized by both mental and physical symptoms that included laziness, drowsiness, an insensitivity of the skin, and seeming to be invulnerable to the pain of a punishment.

There were behavioral problems, too, things like stealing, breaking equipment, abusing animals, and cutting up the crops they were tending "as if for pure mischief." He said it was much more noticeable among free men who didn't have someone to keep them on the straight-and-narrow path, out of the drink, and focused on their work, but that improperly treated slaves could show signs of it, too.

Cartwright claimed the disease was "universal among free negroes" and said while northern abolitionists wrongly attributed these issues to the lasting effects of slavery, he believed they were just all born with this condition. Cartwright? Cartwright was born a condition called Being a Racist Jerk.

Female hysteria was just misogyny

Whoever first came up with the idea of female hysteria probably had no idea that we'd be thinking this was an actual thing for somewhere around 4,000 years...give or take. According to research done by historians at the University of Cagliari in Italy, the idea seems to have started with an ancient Egyptian belief written about in 1900 BC, and it was only removed from the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III) in 1980. Given this massive time frame, it's not surprising there's a whole list of symptoms attributed to female hysteria, including seizures and a feeling of imminent death in ancient Egypt to possession by the Devil in the Middle Ages to the pretty loose definition of a "disturbance of function" that can't be explained by a definite, physical condition in the 19th century.

Basically, any woman who couldn't be neatly fit into society's accepted definition of how a woman should act could be called hysterical, and that's exactly how it was used. Women weren't intelligent, liberated, or their own individual person...they were sick.

Treatments varied just as much as the symptoms, and ranged from prescription herbs and exorcisms to genital massage. You might think you know where this one's going, and you're right. According to The Conversation, treatment included the development of an electrical device for exactly that sort of thing, and it became the modern vibrator. We find inspiration in the weirdest places sometimes.

Absinthism had a darker cause

There's no kind of alcohol that's quite as misunderstood—and vilified— s absinthe. According to the story, absinthe contained enough thujone to cause hallucinations and drive people mad, and it was banned. It wasn't true at all, but in the 19th century absinthe haters made up a medical condition to prove their point about just how bad for you absinthe was, and they called it absinthism.

There was a series of so-called studies done throughout the 1800s, and according to research published by BioMed Central, the studies claimed absinthism was characterized by seizures and hallucinations leading to brain damage, oesophageal cancer, and an increased risk for suicide. There were also citations of softening of the brain, psychosis, paralysis, delirium, and "hallucination insanity" which is exactly what you think it is, and it's no wonder people were terrified of it. Much of the supporting evidence came from some horrible experiments where animals were injected with pure wormwood, leading us to wonder just who the animal really is here.

Today, we can re-classify a lot of the symptoms of absinthism as belonging to chronic alcoholism. Absinthism was condemned as total BS by a portion of the population even in the mid-19th century, but haters gonna hate, especially when it comes to The Green Fairy.

Undeveloped ovaries and the other dangers of novel-reading

What's a better way to spend a quiet Sunday afternoon than absorbed in a good book? Sure, books are great now, but in the 19th century they were the source of all kinds of medical problems—especially for women. For real. Supposedly.

There was never any real name given to the problems developed by the chronic novel-reader, but everyone from medical professionals to education advocates wrote about just what would happen to the woman who spent too much time with her nose in a book and, presumably, getting all kinds of inappropriate ideas. History Buff compiled some of the accounts, and they include things like brain and eye damage, a degeneration of the nervous system, a so-called "female depravity", moral decay, and even an early death. Most troubling to these 19th-century doctors was the idea that there was all kind of energy being putting into reading these novels...energy that would have been better off being used by the reproductive system to stay healthy and fertile.

Read too much—especially when it was something like a mystery—and you could end up with underdeveloped ovaries. Keep reading, and it'd drive your poor little female brain absolutely batty. Sure, you might lose a few IQ points reading some YA paranormal romance, but insane? That might be going a little too far.

Alcohol-related spontaneous combustion

Sure, there's probably some things you still believe about alcohol that just aren't true, but what if we told you there was once an honest-to-gosh belief in the possibility that drinking too much would cause you to spontaneously combust? According to The Daily Beast, there were around 50 cases of alcohol-related spontaneous combustion recorded between 1725 and 1847, because hey, everyone has to go some way.

Victims of spontaneous combustion were often reported to be alcoholics, and the rumor-mongers started spreading the idea that once ingested, alcohol would turn into some kind of flammable gas that would accumulate and eventually explode.

The cases were pretty convincing and extraordinarily graphic, like the story of a 180-pound woman who was reduced to 12 pounds of ash after downing a quart of whiskey and then going up in flames. Even Charles Dickens was a huge supporter of the theory, and wrote about it in Bleak House. If there was ever any real doubt (and there was), that didn't stop the Temperance Movement (via SUNY Potsdam) from picking up on the idea and adding it to their teachings as just one more reason alcohol was evil. They were following in the footsteps of a series of anti-liquor crusaders who said anyone who drank was courting a fiery death, and honestly, that's a chance we're willing to take.

Syndrome K saved lives

Not all made-up medical conditions were created to sell a product or persecute an entire group of people, and when an Italian doctor named Adriano Ossicini came up with the mysteriously-named Syndrome K, he did it to save lives.

According to Quartz, it started in 1943 when the Nazis began raiding areas around Rome's Jewish Ghetto. Families started fleeing their homes, and some headed to the Fatebenefratelli Hospital (pictured) on an island in the middle of the Tiber River. Entire families were quarantined in rooms, and according to their charts, they had contracted the deadly "Syndrome K" which doctors described as being highly contagious and a bit reminiscent of tuberculosis. "Patients" were told to make sure they coughed if any official-looking men came through. No German soldier was going to open a door to a room full of highly infectious patients, which is a good thing, because if they had bothered to check, they would have found perfectly healthy families who were being hidden from the almost certain death they would have found in Nazi concentration camps.

In 2016, the Raoul Wallenberg Foundation recognized the efforts of the hospital staff and named the sanctuary the House of Life. At the ceremony were several of the doctor's Syndrome K patients, including Luciana Tedesco, who said, "I think that there was no patient in this hospital. All the people I saw were healthy. We were refugees who found a home here."

Autistic enterocolitis is totally discredited

Andrew Wakefield is the discredited author behind a paper that first linked vaccines with autism. The retraction of the paper has been well documented, but in 2010 the BMJ took a look at part of his claims that weren't as widely condemned: the existence of something he called autistic enterocolitis. According to Wakefield and his supporters, this was a special kind of gastrointestinal disease only found in patients that had also been diagnosed with autism. Sounds questionable, doesn't it?

BMJ journalist Brian Deer says that's exactly what it is. It's well known that Wakefield's study was funded by solicitors looking for a link between vaccines and autism, and hey, that makes it super-convenient that's what he claimed to find. But they were also looking for a brain or bowel disorder that could also be linked to vaccines...and hey again, that's exactly what he claimed to find. Funny, how that works. Deer took a closer look at what hospital actually found, and as you might imagine, they were actually called "unexceptional" results. Conveniently, the original slides and samples weren't available, but a reinterpretation of the result found that everything was pretty normal.

What remains unclear is motive. Whether or not Wakefield committed some serious scientific fraud or if it was just a misinterpretation of the data, well, we'll leave that up to you to decide.

Wind turbine syndrome is just normal life

You've probably heard of wind turbine syndrome, and it's a "medical" condition that supposedly originates from—not surprisingly—wind turbines. It's championed by entire groups who are campaigning against the development of the clean, renewable energy source that is wind power, and at the top of their list of reasons why this is scary is the idea that the low-frequency sounds emitted by the turbines are going to turn your innards to jelly.

According to the experts consulted by The Atlantic, there's a whole bunch of science-y reasons that's not going to happen, and we won't get into all of them. But we will say wind turbines have been blamed for everything from blurred vision, nausea, panic attacks, insomnia, and headaches, in spite of the fact that we're exposed to constant, low-frequency sounds all the darn time. We should also mention wind turbine syndrome first came from a pretty questionable source: a pediatrician named Nina Pierpont, who (Popular Science points out) is married to an anti-wind power activist.

Popular Science also says not only are the symptoms all pretty much a normal part of being human, they also point out just what the power of suggestion can do. What about you? Right now, do you feel a little headachy? A little bit of mild nausea that wasn't even noticeable until someone mentioned it? Did you have trouble sleeping last night? You might have a syndrome...although, probably not, unless you count humanity and it is sort of contagious.

Train passengers could come down with a case of 'railway spine'

The 1800s were a time of massive change, and one of those big changes was the way people traveled. Trains had become incredibly popular, but they were also incredibly dangerous. They tended to jump their tracks — a lot — and when it came time to clean up the mess, there were a lot of patients to deal with. According to the UK Science Museum, it wasn't long before doctors realized that not all those who were involved in train crashes had easily recognizable injuries of the blood-and-broken-bones variety. Some suffered from chronic exhaustion, pain, and trembling, which physicians chalked up to what they called "railway spine."

At the time, it was thought to be essentially nerve damage caused by the impact of a train derailment, and honestly, that sounds pretty legit. But there was a ton of controversy surrounding it, as railway companies were convinced this conveniently invisible injury was just a diagnosis that would allow supposed patients to sue for compensation. Doctors, however, insisted it was very real — and, as a side effect, giving people a diagnosis of something physical helped keep them out of asylums as they could point to proof it wasn't all in their heads.

What was it, really? According to Australian experts published in Pain Reviews, the diagnosis was later pushed aside in favor of one that focused on the mental and emotional trauma of being in a potentially deadly accident.

When not getting a man would drive a woman insane

Oh, the good old days, when social norms for women included getting married and spitting out a bunch of kids. Unfortunately, it was also the same time — the Victorian era — when those who decided not to follow the traditional route when it came to life choices weren't exactly lauded for their non-conformity.

And that's why history features a little gem called Old Maid's Insanity. According to The Suffering of Women Who Didn't Fit, this was the diagnosis often handed out to women who didn't marry or have kids — women called "unattractive old maids about from forty to forty-five" by the doctor who coined the term.

His name was Dr. T.S. Clouston (via Sex, Sufferage and the Stage), and he was very specific about the symptoms. He believed that a single, childless woman would get to a certain point in her life, realize what she'd missed out on, and be driven insane. The biggest symptoms, he wrote, was that she would become obsessed with an inaccessible acquaintance, usually a member of the clergy, and believe the feelings were reciprocated. While he didn't entirely believe in recovery, he did say that attaching a leech to a person's... lady-parts would help relieve the depression and madness. Needless to say, we don't believe this anymore, because: progress.

It's always all about the poop

Buckle up, because this is about to get gross. Going all the way back to Ancient Egypt, there was a very real possibility a patient might be diagnosed with intestinal autointoxication. And what is that? Basically, it meant that old poops had started to putrefy inside of the person, and were causing all kinds of issues.

Over the centuries, the same general idea was superimposed over the Ancient Greek belief that the body was controlled by the four humors. Physicians here believed that not only could food rot inside you, but any residues produced by the body's blood, phlegm, and bile could get equally rotten and toxic.

It sort of makes sense, and even though TS Chen of the Department of Pathology at the East Orange Veterans Administration Medical Center notes that it was largely discredited in the scientific and medical communities by the 1920s, it's entirely possible the idea still may crop up. It still sort of circulates through the public consciousness, and that's not to say it's unimportant. Discredited as the idea is, researchers from the University of Glasgow say it helped form the basis of the idea that the bacteria of the gut microbiome is directly linked to health.

Rule One of disease creation: at least figure out the symptoms

It's not even necessary to go back into the darkest depths of history to find some bizarre medical diagnoses — there's one just a short hop, skip, and jump back to 1986. That, says Science Based Medicine, is when the oddly-named Dr. William Crook created a fake illness around something perfectly ordinary. That was Candida, a benign fungus found in around 90 percent of the population. Most of the time, it's harmless. When it gets out of control it can cause things like thrush but again, that's not what we're talking about.

Crook pitched the idea of Candida hypersensitivity, which was basically, well, everything. Healthline says that he had a laundry list of symptoms associated with the "disease," including infertility, anxiety, both constipation and diarrhea, weight gain, hives, and a general sort of just feeling bad. He also said that about a third of the American population suffered from this allergy to yeast, and unsurprisingly, a whole industry sprang up around creating supplements to fix the problem.

While yeast allergies do exist, they're relatively uncommon — and they're not the same thing Crook was pitching. (He, incidentally, had his medical license put on probation.) Candida hypersensitivity was blamed for hundreds of different symptoms, and it was even claimed that cancer was a similar sort of fungus. It's not. It's definitely not.

Giving a name to unexplained death

The death of a child is tragic no matter what the era of history, and it appears the condition that would become known as status lymphaticus was first described in 1614. The physician was Felix Plater, and he was trying to find the cause of the death of a 5-month-old boy. The only abnormality he found was an enlarged thymus, and according to research published in Annals of Internal Medicine, this became the basis of the condition.

By the 1930s, doctors were describing (via The American Journal of Surgery) the condition as "a combination of hereditary constitutional anomalies," and linking it to sudden and otherwise unexplained death.

Ann Dally, of the Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine, says that status lymphaticus was essentially created as a more modern way of saying a death had been caused by "a visitation from God." It was almost never diagnosed in a living patient, and the official definition was "a disease that resulted in sudden death." It was included in medical textbooks well into the 1950s, but since then has fallen completely out of favor. As medical knowledge advanced, there were no more "mysterious" deaths due to the regular use of chloroform as a sedative, and many sudden deaths became explainable by other means, like anaphylactic shock or myocarditis.

Live fast and die young

Live fast and die young, the saying goes, and back in the 19th century, there was a name for that: neurasthenia. Here's the thinking behind it. Doctors S. Weir Mitchell and George Beard were practicing at a time when a lot of things were changing. The American Civil War had just ended, and an agricultural country was making a marked swing toward city life. That brought a whole different set of challenges to people, and at the time, it was believed the nervous system was a limited resource, and it was easily overwhelmed by all these new problems popping up for a newly industrialized country. When people spent all their "nervous energy" they became exhausted, and that? That's neurasthenia.

According to The Atlantic, symptoms included depression, anxiety, fatigue, headaches, irritability, and insomnia. Where many illnesses are caused by a virus or bacteria, this was caused by a rapidly developing change in the American lifestyle. Psychologists even nicknamed it "Americanitis," and the root of the problem was believed to be that America had quickly out-paced other countries, and their citizens just couldn't deal with the pressure.

Strangely, men who were diagnosed were often sent to the frontier to essentially be cowboys, while women were prescribed four to six weeks of bed rest. The entire idea fizzled out in the 1920s, when medical researchers confirmed that the nervous system doesn't actually work like that.

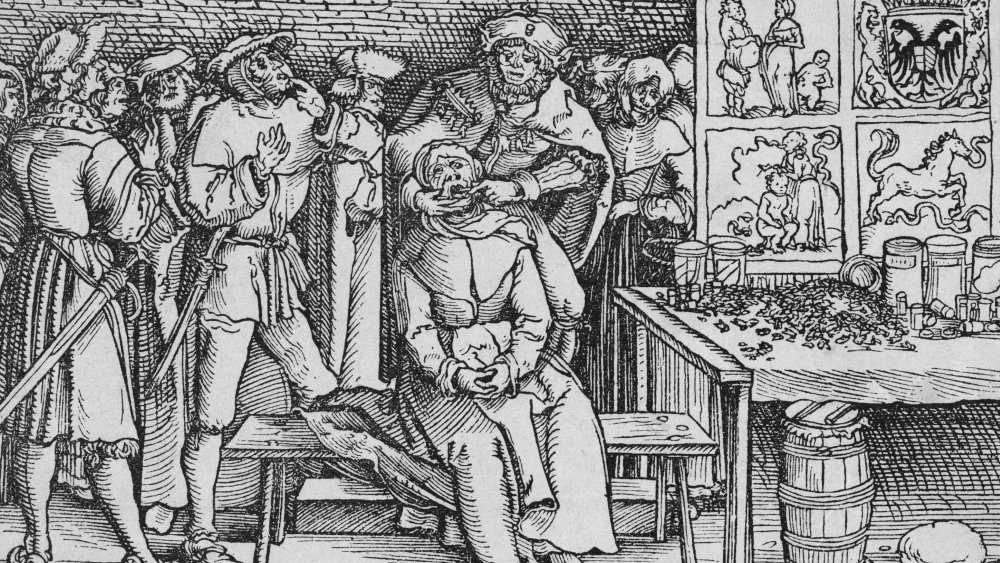

No one has ever liked the dentist

Today, we know what causes cavities: bacteria, sugar, and poor dental hygiene, says the Mayo Clinic. Way back in ye olden days of the Middle Ages, the explanation was much more disturbing than "you don't floss, do you, you heathen?"

Exarc took a look at the translation of a medieval Dutch text about dentistry and remember, the predominant medical theory at the time was that the body was governed by the four humors. When the humors got cold and rotten, worms would take up residence wherever they could ... and apparently, they liked the teeth. According to the text: "Sometimes worms are growing in the jaw as you will know, when these worms lay still the teeth do not hurt. But if they are moving then it hurts." Good luck not thinking about that the next time you have a toothache.

This wasn't just a random belief, either. According to Science Direct, there really are worm-like structures inside some teeth. Researchers weren't sure what, exactly they were... but hey, here's some good news: they're not actually worms. Small miracles!

A catch-all way to get rid of someone

Lunacy: it's a well-known diagnosis of the Victorian era, and it was essentially the sort of madness that would get someone committed to an institution. The University of Wisconsin says there were a ton of different reasons a person — most often, a woman — could be diagnosed as a lunatic, and they were things like depression, "religious excitement," mania, dementia, overexertion, and epilepsy.

It's also pretty well-known that when a husband or father wanted to get rid of a wife or daughter, a diagnosis of lunacy was a common way to do it. But historian Sarah Wise discovered something fascinating when she started looking through patient records (via Psychology Today): men were just as frequently dumped in those same asylums.

While men had the option to abandon wives and families and take up with another, women didn't have that — partially because of societal norms, and partially because men controlled the money. But women wanting out did have an option: have that husband committed. Not only would she be rid of him, but she'd get control of property, finances, and assets. This was, after all, a time when Evangelical beliefs preached that it was a man's responsibility to provide a safe and loving home for his family, and with just a few words to a sympathetic doctor, well, there were plenty who were happy to get a lady out of a desperate situation... whether it existed or not.

Here's what to say the next time you call in sick

In 1990, E. Denis Wilson took a crack at defining the illness characterized by symptoms every person is pretty familiar with: random aches and pains, difficulty concentrating, a sluggish metabolism, and fatigue. The Hormone Health Network says that he decided these very common complaints — along with a low temperature — were the consequences of a thyroid hormone deficiency, but not a deficiency so drastic that it would show up on most tests. Wilson prescribed pharmaceutical preparations as a cure, and as wonderful as it sounds to have a tried-and-true cure for the daily doldrums, it wasn't exactly legit.

That's because there's no such thing as Wilson's syndrome, and that's according to The American Thyroid Association. Not only has there been no scientific research done that's been able to support the theory, but the symptoms are incredibly common things that can be explained by a number of different causes. Criteria, they say, is too imprecise to be accepted as a legit medical diagnosis, and unfortunately, that can actually be dangerous. Wilson attributed 37 different symptoms to his disease, and some are signs of a legitimate thyroid problem. Writing them off as Wilson's syndrome and not getting treatment for the real problem, well, that's not a good thing. They also point out that previously, the same set of symptoms were described by numerous other names, including neurasthenia and chronic candidiasis.

Everyone gets a bit of this at some point

The term "nostalgia" dates back to 1688, and it's rooted in the Greek words for "homecoming" and "pain." That's pretty accurate: get a strong enough case of nostalgia, and it really can physically hurt. But it's not a disease — even though for a long time, it was thought to be exactly that.

According to The Atlantic, there are records of soldiers being discharged from military service because they came down with it — and Swiss soldiers were so susceptible that the playing of a particular traditional song was punishable... by death.

At the time nostalgia was termed a disease, it wasn't just a bit of melancholy. Other symptoms included fever, cardiac arrest, and even brain inflammation — clearly, something else was going on here. Still, treatments were harsh: in 1733, one Russian general made it clear that the first one of his men to be diagnosed would be buried alive, and did he do it? Of course he did. Treating by fear morphed into treating by shame by the time it made it to the US, and while nostalgia is still definitely a thing, it's no longer a disease that needs treatment.

Does WiFi make life unbearable?

In 2013, The Guardian interviewed Tim Hallam, who said he was suffering from electromagnetic sensitivity. He had lined his rooms with tin foil to keep out the signals, which Hallam said came from everything from WiFi to fluorescent bulbs. Exposure to the frequencies left him suffering from insomnia, irritability, headaches, muscle pain, memory lapses, and dry eyes. Others who claim to have similar sensitivities wear clothing made with protective materials, paint their walls with carbon paint, and of course, tin foil is common.

So, is electromagnetic hypersensitivity (EHS) real? The World Health Organization says that it's complicated. While they say that "symptoms are real," they add that there's such a wide variance in symptoms between individuals that there is no diagnostic criteria, and no way to classify it as an actual medical diagnosis or single problem.

LiveScience goes a step farther, and cites a series of studies where people who claimed to have EHS were exposed to conditions where they didn't know if electromagnetic signals were on or off... and they couldn't tell when signals were present. Researchers aren't denying that there's something going on here... they're just pretty sure that these electromagnetic signals are merely a scapegoat.

How far could it really wander off?

In Ancient Greece, one of the most serious afflictions a woman could be diagnosed with didn't even exist. It was the idea that a womb could just up and decide to go off on a jaunt around the abdomen, colliding with other organs, pushing them out of the way, and causing all kinds of chaos. The symptoms were surprisingly well-established. If the patient complained of a sudden feeling of weakness, vertigo, and fatigue, the womb was working its way upward. If there was a feeling of choking, difficulty speaking, and — in the worst of cases — sudden death, then it was heading downwards.

Physicians believed the womb was very strongly in tune to smells, and would use scents — either inhaled or applied to the afflicted's lady-bits — to push or lure the womb back into place. But if women followed advice, it wouldn't be a problem. The key was to keep the womb occupied and busy, which meant keeping it pregnant.

According to Wired, belief in the wandering womb lasted a long time — at least well into the 12th century. By the 15th, it didn't wander anymore, but it was still responsible for women being the irrational creatures they are... said the men in charge.