The Truth About Caesar And Pompey's Relationship

In the most brutally competitive and warlike society in human history, one rivalry stands out: Julius Caesar and Pompey Magnus. These men were the warrior vanguard of the doomed final generation of the Roman Republic, and their friendship-turned-feud was the last gasp of a badly broken democratic system that would give way to 500 years of tyranny.

In the few generations before the time of Caesar, Rome's military might earned the city-state a vast and fantastically wealthy empire — though it remained governed by a small Senatorial class who squabbled internally for power. It was this great game of king-of-the-mountain that drove Roman elites to strive for history-making achievements. But the competition had long since turned ugly. Pompey's mentor Sulla, a vaunted general himself, had in his own feud with a decorated rival named Marius. In the closing salvo of that clash, Sulla defied sacred custom and marched on Rome in 88 B.C. What ensued was a horrifying political purge. A then-teenaged Caesar barely escaped these murderous "proscriptions."

Caesar and Pompey grew up in a world where politics was a blood sport. All governments are run by custom as much as law, and the Roman social contract was badly broken. Both men witnessed firsthand that the only thing more dangerous than striving for power was losing it. Sulla's purge was a naive attempt to restore Rome's governing traditions by force. Caesar and Pompey took the true lesson: the Republic was already dead. It was time to decide who rules.

Julius Caesar was Pompey's father in law

Though Julius Caesar was the younger man by six years, he became father-in-law to Pompey Magnus when he offered his rival his favorite daughter, Julia.

Caesar and Pompey both had something the other wanted. Caesar hailed from one of the oldest and noblest families in Rome. He claimed direct ancestry from the god Venus, notes History. Pompey was plebian by birth. It did not matter how many nations he conquered; in the eyes of the aristocratic senate, he would always be a grubby little climber. A wedding to a great family not only legitimized Pompey but would give his children with Caesar's daughter a lineage he could not win by battle.

Caesar's interest in a marriage alliance with Pompey was practical, too. The powerful general who controlled his own private army once credibly boasted, "I have only to stomp my feet and legions will spring up," via "Decline and Fall of Pompey the Great." The marriage between 17-year old Julia and 47-year-old Pompey in 59 B.C. avoided that outcome, as Pompey and Caesar formed an alliance to rule together called the First Triumvirate, notes Britannica. But when Julia died in childbirth a few years later, civil war soon followed.

Julius Caesar envied Pompey

Pompey had something else Julius Caesar wanted: military esteem. Being slightly older, Pompey's achievements in war naturally preceded Caesar's. But Pompey was also a precocious prodigy. At 23, he joined the staff of infamous Roman tyrant Sulla with legions inherited from his father. Soon Pompey was known as the "teenage butcher," for his youthful brutality. Sulla even broke with convention and awarded Pompey Rome's highest honor, a triumph, even though his pupil was technically too young, per the World History Encyclopedia.

It was around this time Pompey took the name "Magnus" meaning "the great" — a reference to Alexander the Great. Grecian imports from philosophy to fashion were all the rage among Rome's upper crust, despite the republic's intensely nationalist leanings and suspicion of foreign customs. But in this militaristic society, no figure had higher esteem than Alexander, who had conquered the known world by age 32 (via History). The Greek general was the heroic standard to which Pompey and Caesar both aspired.

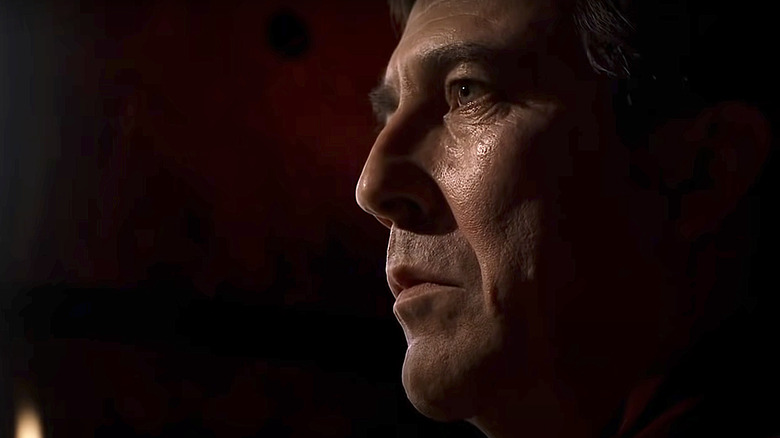

The Roman historian Plutarch had this in mind when he painted a perhaps apocryphal scene of Caesar weeping at the foot of a statue of Alexander in Africa. Caesar, unlike Alexander or Pompey, had not inherited an army, just a name. Whereas Alexander and Pompey peaked early, for Caesar to outshine his rivals — both contemporary and those of the misty past — he would find himself charging headlong into battle well into middle age.

Pompey was born rich and Caesar was born broke

Caesar came from a noble family in Rome, but the Julio-Claudian clan had fallen on hard times. Their prodigal son wasn't born to the kind of cash he needed to finance a run through Rome's senatorial hierarchy. Caesar's rise was like a political Ponzi scheme of borrowed favors and cash. He was so deeply in debt by the day of his election for Pontifex Maximus in 63 B.C., he told his mother if he did not come home victorious, he would not come home at all, according to The Twelve Caesars (via Public Seminar).

Pompey was decidedly lowborn by lineage but was the son of a wealthy "new man" in Rome. This was the aristocracy's somewhat derisive term for Rome's increasingly powerful nouveau riche. Rome's blue bloods had long looked down on the drudgery of business, and this left room for a class of knights, called Equites, to form an influential corporate class.

Pompey's father Strabo was from Picenum, one of the many allied Italian regions under Roman control. Strabo started from the bottom but rose all the way to Rome's highest office of Consul, according to Penn State. When Strabo died in battle in 87 B.C., Pompey was just 20 years old. He inherited his father's lands as well as a semi-private army loyal to him. It was everything an ambitious young Roman needed to climb the Roman social ladder.

Caesar and Pompey were political opposites

Rome in the time of Pompey and Caesar was divided along lines that might still be recognizable today. Despite being born to a plebian family, Pompey fought for the old-guard (via History Collection) on the side of Rome's aristocratic class of "Optimates." Blue-blooded Caesar, on the other hand, took up the cause of the lower classes. Caesar's "Populares" had long battled Rome's elites for greater influence. According to writer Frank Smitha, Caesar pushed progressive reforms such as minority rights for Jews, voting rights among Italian allies, and land allotments for war veterans.

The Populare cause was in some sense a romantic countercultural movement, too. And Caesar wasn't just a populist; he was fashionable. He famously wore his toga "loosely belted" and was even branded "effeminate," notes History Collection. His leadership among Rome's cool kids contrasted Pompey's closer embodiment of what had always been paramount to the republic: tradition.

These recognizable class and culture wars, however, were hardly straightforward to interpret. The Populare cause was also synonymous with demagoguery since Rome's founding; the republic itself was created upon the exile of Rome's last king. And while Pompey was never known for his oratory or shrewd maneuvering inside Rome's power structure, Caesar was a cunning political tactician whose enemies assumed his populism, and his fashion sense, were a shrewdly calculated route to kingly tyranny. He, of course, proved his detractors correct when he named himself dictator for life in the year 44 B.C., according to National Geographic.

The sex scandal that nearly toppled Julius Caesar

In 62 B.C., Julius Caesar was caught up in the most salacious sex scandal of antiquity, and it seriously threatened his viability to contend with the mighty Pompey Magnus for glory.

The Scandal of the Bona Dea begins with a flamboyant and handsome young populist aristocrat named Clodius Pulcher. Like the philandering Caesar, Pulcher was a womanizer and may have given Caesar a taste of his own medicine when he tried hooking up with Caesar's third wife Pompeia, according to Plutarch.

At the time, Caesar was the head of Rome's church, a political appointment called the Pontifex Maximus. Every year, the Pontiff's wife would host a sacred ladies-only soiree in the Aventine temple. Men were so verboten they supposedly didn't even know the god being honored, notes Today In History. Clodius, therefore, disguised himself as a woman and snuck into the temple to seduce Pompeia, but he was quickly caught and arrested. The ensuing scandal led to a two-year courtroom drama. Caesar quickly divorced Pompeia but refused to testify against Pulcher. He could ill afford to alienate a key populist ally given his desire to outdo the Optimate-aligned Pompey, who had celebrated a massive triumph the prior year. Caesar also couldn't admit to being a cuckold without losing face. But then why divorce Pompeia? From the witness stand at Pulcher's trial, Caesar wriggled out of this contradiction with the legendary line, "the wife of Caesar must be above suspicion."

Caesar and Pompey once ruled Rome together

Besides Julius Caesar dubbing himself dictator for life in 44 B.C., the rise of the First Triumvirate in 60 B.C. is another reasonable date marking the fall of the Roman Republic. For centuries, Roman senatorial elites had self-governed by the committee, and this coup portended the end of this ancient democracy.

Caesar, Pompey, and Rome's richest man Crassus divided rule between themselves in a power-sharing agreement that lasted just seven years until it dissolved in 53 B.C. The trinity was good for the conspirators as long as it lasted. Pompey had won massive victories by 61 B.C., and the Senate feared the popular general would march into Rome and become a tyrant like Sulla. Instead, Pompey humbly disbanded his forces and entered Rome as an ordinary citizen. He asked only that his veterans receive land grants and that his conquests be ratified. But when these reasonable requests were thwarted by a partisan rival, Pompey plotted to circumvent the senate entirely.

Caesar had his own grudges with senators bogging down a well-precedented request to be elected to a key post in absentia. Neither man's beef was in itself radical. Perhaps that seeming moderation is what attracted Crassus and his riches as the "glue" that held this three-way alliance together, according to World History Encyclopedia. But when Crassus was killed in a reckless war of aggression in 56 B.C., the fragile detente between Pompey and Caesar soon died too.

Pompey put Julius Caesar in an impossible position

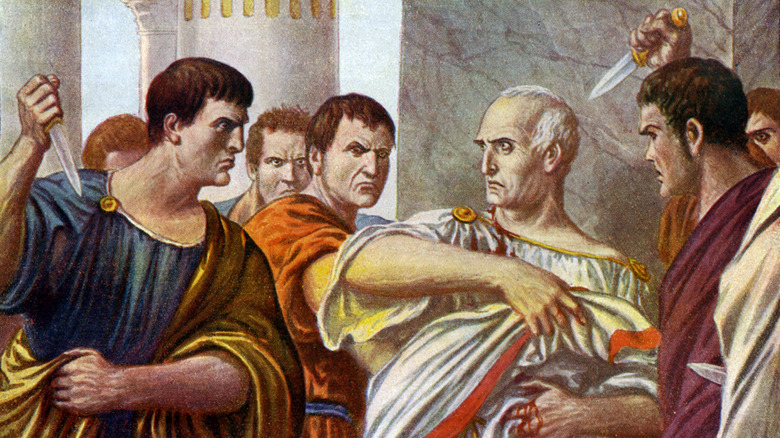

In 49 B.C., Julius Caesar was in a real pickle. He had been gone from Rome on a long military campaign because he needed the spoils to pay back the massive loans that funded his political rise. His victories had secured the loot, but now the Roman senate demanded he return home in disgrace. Pompey, Caesar's once Triumvirute ally, was backing their play.

All this hinged on a funny rule in republican Rome (per "Judicial Accountability and Immunity in Roman Law"): government officials could not be prosecuted. Pompey's new father-in-law Scipio had been waiting for Caesar's title to lapse so he could drag him into court and ruin him politically and then send him into exile, or worse. Caesar was desperately attempting to secure another title before his previous appointment lapsed, thus retaining immunity. When his efforts failed, the senate wanted to declare him an enemy of Rome, notes Plutarch.

Caesar had two things on his side: a battle-hardened army loyal directly to him and the admiration of ordinary Romans, per Livius. The Senate had legal authority, but no power of enforcement. Only Pompey's military backing could make Caesar come to heel. Caesar had implored his old pal Pompey for peace, but was refused. Thus, Caesar faced a choice: fight a ruinous civil war, or let his enemies destroy him. Since ambitious Romans of the era did not consider submission a viable option, Caesar would soon turn his army on Rome and face Pompey in a war that would end the Republic for good.

The Gods favored Caesar over Pompey

Julius Caesar and Pompey weren't just opposites in style and politics. Their military reputations were also mirrored images. Per the "Oxford Classical Dictionary," Pompey was renowned as a master of logistics on the battlefield. But, maybe, though, it's better to be lucky than good. Caesar was better known as a man whom fortune had chosen, as explained in "Julius Caesar's Luck." For Romans, luck was a divine blessing, and Caesar was the Tom Brady of happy accidents on the battlefield. He was not only clutch under pressure but always seemed to pull out the improbable comeback win (via UNRV).

After Caesar marched his soldiers into Rome in 49 B.C., Pompey and his senatorial allies fled to raise their own armies. The former friends faced off in a final showdown in 48 B.C. at the Battle of Pharsalus. Pompey's army was larger and all but had Caesar's troops cornered. Roman soldiers were great builders, and the two camps had been skirmishing for months between an ever-enlarging series of walled fortifications, per History Hit. Perhaps at the goading of senators, Pompey inexplicably came out from behind his walls and faced Caesar's superior but smaller veteran force in open battle. Caesar's cleverness and aggression broke Pompey's line, and suddenly the man who had never before lost a battle barely escaped with his life.

The Roman Senate tried to pit Caesar and Pompey against each other

The famous Roman orator, lawyer, and politician Cicero long feared Caesar and Pompey had become too powerful for the republic to survive. And as with any two great polar powers, the only way to beat them was to play one against the other.

During the initial stage of Rome's civil war, Pompey and the senatorial class fled the city while Caesar occupied Rome and assumed dictatorial authority. Cicero did not immediately flock to team Pompey, however. He bravely stayed behind and negotiated with Caesar, hoping some settlement could be reached. Only after much indecision did he join Pompey on his campaign. Cicero had long played both sides and had even tried to break up Caesar and Pompey's triumvirate alliance in 57 B.C., according to Britannica.

After Caesar's assassination, Cicero again attempted to broker a ploy using Caesar's direct military successor Mark Atony, and Caesar's adopted son Octavian — who later became Emperor Augustus. But when Cicero underestimated Octavian's duplicitousness he again found himself on the outside looking in as a new triumvirate was formed. In 43 B.C. Rome's best-known orator was caught and killed by Caesar's less forgiving successors. In a symbolic gesture that senatorial statecraft was dead, Cicero's head and hands were nailed to the rostra in the Roman forum for all to see.

Caesar wanted to reconcile with Pompey

After losing to Caesar at the decisive battle of Pharsalus, Pompey fled to Egypt disguised in the rags of a peasant. Pompey's greatest achievement in his many military conquests had been the erection of a vast administrative state. Even kings were mere vassals to Pompey, and this included the teenage sovereign of Egypt, King Ptolemy XIII, who was both the younger brother and husband to the legendary Cleopatra.

Of course, the incestuous marriage was also a sibling rivalry. Cleopatra had ambitions of her own and had fled Alexandria. It was in this tense atmosphere that Pompey landed in Egypt. King Ptolemy, realizing Caesar was now the clear authority of Rome, ordered Pompey's assassination. With his wife looking on, Pompey was stabbed to death before he even set foot on dry land, according to Plutarch.

When Caesar arrived in Alexandra, however, he was far from pleased. Caesar's "clemency" was one of the general-politicians' favorite tactics. He set himself apart from Sulla or even Pompey with a political policy of mercy. He loved to pardon fallen foes, thus putting them in his debt. Pompey's murder denied him this vanity and the legitimacy a renewed friendship could offer. Caesar even mourned Pompey, notes Britannica, and his displeasure would soon be felt. Within a year, King Ptolemy XIII was dead (via Britannica), Cleopatra was installed as Queen, and the new regent was carrying in her belly Caesar's only born son, Caesarion.

Caesar showed respect for Pompey after his death

Pompey was the king of Roman triumphs. He held the most lavish victory party in Roman history, bringing so much loot home his spoils dwarfed the already swollen coffers of the Roman treasury. His history-making third triumph in 61 B.C. (via Britannica) made him the first Roman general to celebrate a triumph from victories on three different continents. Such was the party's largesse, "much of what had been prepared could not find a place in the spectacle," according to Plutarch in his magnum opus, "Parallel Lives."

After Caesar defeated Pompey in the Roman civil war of 48 B.C., Caesar outdid his old foe by holding exactly four straight triumphs over a series of two weeks in 46 B.C.. It was against Roman custom to celebrate a triumph for victories in civil disputes, so ostensibly, Caesar's parades were all held for his various other feats of derring-do in Africa and Gaul.

However, some of the parade floats featured images of other figures who had died in Caesar's civil wars. This was a rare public relations misstep for the savvy Caesar, and many in the crowd were horrified by these images. However, Caesar was careful not to display any images of Pompey, according to Appian, whom he well knew retained the love and respect of ordinary Romans.

Caesar's competition with Pompey led to his death

Pompey never intended to topple the Roman Republic. He had the chance to be a tyrant and took a hard pass. However, his exploits were a model for how Rome's democracy fell. Per the World History Encyclopedia, like the great Roman general Marius before him, Pompey had a vast army loyal directly to him (via The Collector). He used it to conquer innumerable foreign kingdoms and build a vast network of client states also answerable only to him.

Pompey in many ways styled himself after his mentor Sulla, who had briefly taken dictatorial powers in a violent and bloody purge of Romans who opposed him in 82 B.C (via Britannica). 20 years later, as described by Plutarch, Pompey's lavish third triumph was a two-day celebration for his many foreign victories, and it had him parading through Rome as demigod for a day. He was a dictator in every way but aspiration. Others may have wanted total power, but Pompey contented in simply being the best man among many in Rome.

Caesar, on the other hand, tolerated no peers. Following his own record four-consecutive Triumphal celebrations in 46 B.C., Caesar apparently forgot the traditional incantation whispered by a slave in the ear of a conquering general: "memento mori," or "remember you are mortal." After Caesar's ascent to total power and his almost immediate assassination in 44 B.C., he became officially deified. Caesar's ambition cost him his life, but perhaps only because he had to compete with Pompey the Great.